Traditionally, cartoons were made up of self-contained episodes, about 22 minutes long, meant to entertain kids and then start over. For years, people didn’t expect characters to develop over time or for stories to span multiple episodes – that was reserved for live-action shows or the occasional miniseries. Anime existed, but it was relatively unknown and didn’t have the huge global following it does now. Then came Toonami, a Cartoon Network programming block with a cool, futuristic look, which appealed to a growing number of young viewers who were looking for something different. This gave anime a platform, and no show benefited more than Dragon Ball. It’s amazing how close the series came to being cancelled before Toonami stepped in.

I remember when anime was struggling in the US – the dubbing was often poor, it was hard to find on TV, and a lot of American viewers just didn’t ‘get’ it. Then Toonami made a brilliant move: they scheduled Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z back-to-back. It completely changed everything. Suddenly, a whole generation discovered anime through those shows, and it really shifted how Americans saw the medium. People who’d missed the original Dragon Ball could finally start at the beginning and understand everything that was happening as Goku grew from a young fighter to an incredibly powerful hero. That created a real connection and made the story so much more rewarding. Honestly, it gave the series the momentum and cultural impact it needed to really succeed here, and it felt like it saved Dragon Ball in America.

Pre-Toonami, Dragon Ball Struggled to Find Its Western Audience

Before it found a home on Toonami, the American release of Dragon Ball was quite chaotic. The original series, which premiered in Japan in 1986, was a fun and lighthearted martial arts comedy with quirky characters. However, American television networks were looking for more fast-paced action, and the original tone didn’t quite resonate. As a result, Dragon Ball was poorly marketed and shown sporadically on local stations throughout the early 1990s. The version viewers saw was often heavily edited – jokes were rewritten, scenes were cut, and even the music was changed. This led to a disjointed experience, with Goku sometimes appearing as a child and other times as an adult, leaving many viewers confused and ultimately forgetting about the show.

I remember watching Dragon Ball back then, and even though it had a lot of action, it struggled to stay on TV consistently. It first appeared in syndication in 1996, but only included the Saiyan and Namek sagas. Unfortunately, it was canceled pretty suddenly before the Frieza Saga could even finish, because ratings weren’t good. It seemed like the show might always remain a favorite among a smaller group of fans. Looking back, I think the real problem wasn’t the show itself, but how it was presented. American kids were used to episodes that wrapped up neatly each time. Dragon Ball often took dozens of episodes to resolve a single battle, and it expected you to follow a continuing storyline – something a lot of viewers weren’t used to.

What seemed like a flaw at first – a slow pace – eventually became one of the anime’s most endearing qualities. However, back then, it was considered a weakness. Dragon Ball simply needed the right platform to succeed, and Toonami proved to be perfect. When Cartoon Network added Dragon Ball Z to its afternoon lineup, it was a risk. But unlike previous, inconsistent airings, Toonami provided a consistent schedule and a cool, energetic vibe. This consistency drew in a new generation of fans, with kids rushing home to watch each battle.

Toonami Made Dragon Ball a Continuous Story for American Fans

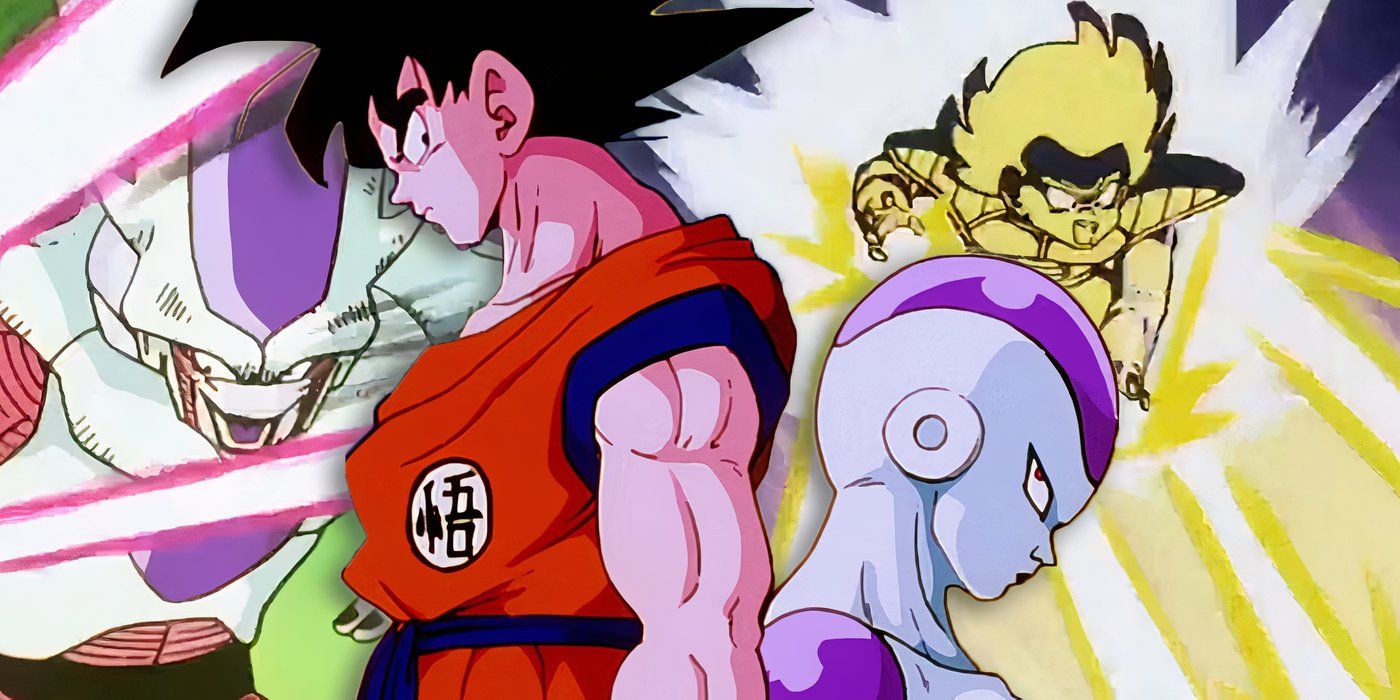

The biggest turning point for the show came when Toonami began airing Dragon Ball immediately followed by Dragon Ball Z. This created a seamless story, letting viewers watch Goku grow up – from his childhood adventures fighting the Red Ribbon Army to his epic battles as an adult against Saiyans and androids. It essentially combined two series into one long, ongoing story, which deeply connected fans to the narrative. This also fixed a problem with how the show was presented to American audiences. In Japan, Dragon Ball naturally led into Z, but in America, fans had seen them out of order. Many only knew Goku as the powerful, shouting Super Saiyan.

Seeing young Goku’s story helped explain why the character was so powerful and inspiring. It suddenly made sense why Goku was so brave, whether he was fighting for his son or facing overwhelming challenges – we could connect it back to his early training with Master Roshi. This was a satisfying result of years of development. Showing Goku’s past and present side-by-side emphasized his growth, making the action feel meaningful instead of just repeating the same patterns. This approach also changed how American television viewed anime. Before Toonami, networks often treated anime as something temporary, airing only a few episodes before moving on to the next thing.

Unlike other channels, Toonami made watching anime feel special. Its futuristic graphics and music created a sense that all the shows were connected. The robotic host, TOM, built excitement for each day’s programming, turning it into an event. In that atmosphere, Dragon Ball wasn’t just another animated series – it felt like viewers were witnessing an epic story come to life.

DBZ’s Cultural Revolution Owes Its Roots to Toonami

When Dragon Ball Z became popular, it quickly captivated a whole generation. Kids who hadn’t previously paid attention to anime were suddenly reciting attack names, discussing character transformations, and arguing about power levels at school. The famous “over 9000” meme originated from the way Toonami integrated Dragon Ball into daily viewing habits. Beyond its own success, Dragon Ball also sparked interest in other anime series. The enthusiasm for Dragon Ball Z helped shows like Sailor Moon and Gundam Wing gain popularity, all thanks to the audience Toonami had cultivated.

By 1999, anime had exploded in popularity, moving beyond a niche interest to become a full-blown phenomenon. Unlike most American cartoons at the time, anime didn’t rely on quick resolutions or self-contained episodes. Viewers were drawn to longer, more involved stories that developed over time – a completely new approach for American animation. Toonami played a key role, connecting audiences with anime while respecting its Japanese roots. They didn’t try to change or simplify anime to fit American tastes; instead, they presented it authentically, allowing the stories to resonate on their own. For many viewers, Toonami was their very first introduction to Japanese storytelling.

The story’s unique tone was a key part of its appeal. Dragon Ball Z expertly mixed over-the-top silliness with genuinely intense moments – it could be hilarious, then incredibly dramatic, all in the same episode. This blend of comedy and seriousness resonated with Toonami’s young audience, who were starting to be recognized as viewers with real preferences. Toonami didn’t just show anime; it truly cultivated a generation of fans and laid the groundwork for the thriving anime community we see today.

Decades Later, the Legacy of Toonami’s Gamble Continues to Grow

Without Toonami, Dragon Ball could have easily faded into obscurity. Instead, the show became incredibly popular. Funimation’s plan to sell Dragon Ball merchandise and dubbed copies only worked because Toonami built a dedicated fanbase. Kids who watched the show daily wanted more, and Funimation was ready to provide it. By the early 2000s, Dragon Ball Z reruns were consistently highly-rated. The show’s success even pushed Cartoon Network to compete with other networks like Nickelodeon and Fox Kids. Dragon Ball became so well-known that even people who had never seen anime recognized moves like the Kamehameha. This widespread cultural impact happened because Toonami consistently presented the series to its audience.

Toonami’s impact goes far beyond just fond memories. It fundamentally changed how American television networks approached anime, demonstrating that ongoing, foreign-made series could attract large, dedicated fan bases if presented well. This paved the way for popular shows like Naruto, Bleach, and One Piece to be aired with little to no editing – a significant improvement over the heavily cut versions of the early 1990s. Toonami didn’t just revive Dragon Ball; it helped establish anime as a legitimate part of American pop culture. When people discuss the growth of anime in the US, they’re often referring to the lasting influence of a programming block that gave one show, and the genre as a whole, the recognition it deserved.

When Toonami broadcasted both Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z, it wasn’t simply using filler content. It was actually sparking a cultural shift. The programming block showed American viewers how to appreciate extended narratives and enjoy animation from other countries. While many other shows were quickly forgotten, Dragon Ball remained popular, largely due to a brilliant scheduling choice – pairing the two series together was a remarkably smart move for anime in the US.

Read More

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Sony Removes Resident Evil Copy Ebola Village Trailer from YouTube

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Can You Visit Casino Sites While Using a VPN?

- Holy Hammer Fist, Paramount+’s Updated UFC Archive Is Absolutely Perfect For A Lapsed Fan Like Me

- The Night Manager season 2 episode 3 first-look clip sees steamy tension between Jonathan Pine and a new love interest

- Frieren Season 2 Highlights New Opening With Final Trailer Ahead of Premiere

- Stranger Things Creators Reveal Which Series Character Was Always Doomed

- Nintendo Switch Just Got One of 2025’s Best Co-Op Games

- Emily in Paris soundtrack: Every song from season 5 of the Hit Netflix show

2025-11-05 20:44