As a film enthusiast who’s spent countless nights huddled in the dark, my dear friends, let me tell you this: I’ve seen a plethora of films that have left me quivering in fear or rolling on the floor with laughter. But none, and I mean NONE, have left such an indelible mark on my psyche as the enigmatic tale spun by the cunning minds behind The Blair Witch Project.

Back in 1997, I was part of an unconventional film crew that ventured deep into the woods, armed with nothing more than handheld cameras and a revolutionary idea. The directors and three lesser-known actors were my companions on this intriguing journey.

Two years later, their footage scared up almost $249 million.

25 years have passed since the release of “The Blair Witch Project,” a groundbreaking film in the horror genre known as found footage. The concept wasn’t just dreamed up, but it didn’t truly take off until 1999. Similarly, the hand-held camera technique that gave the film its unique feel was also new and took some time to become familiar with. There were instances of discomfort, such as nausea and vomiting, reported among viewers.

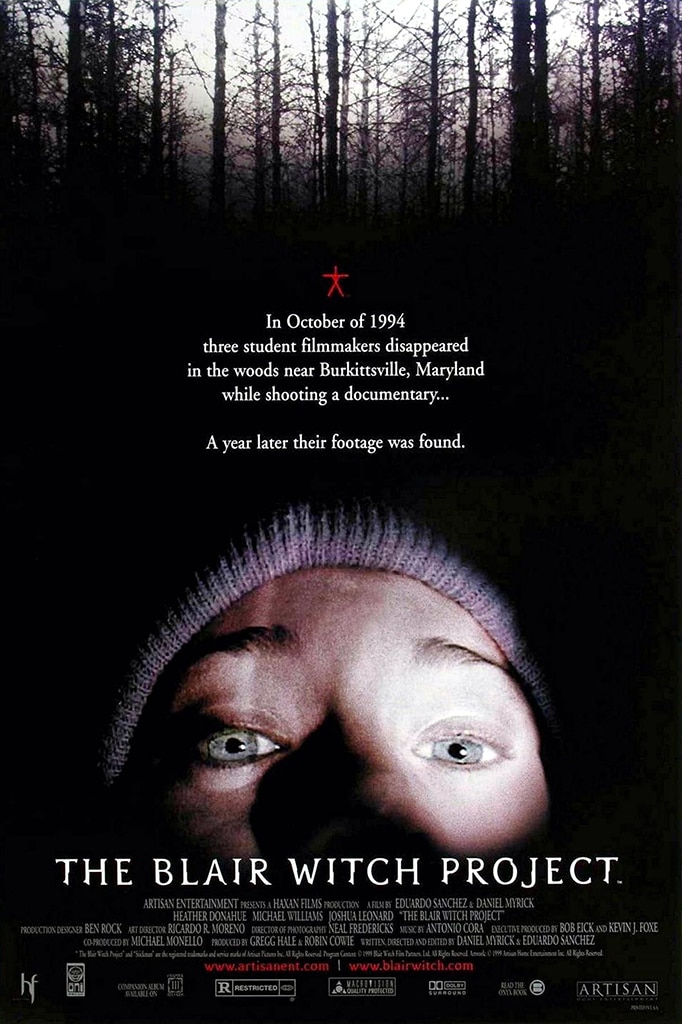

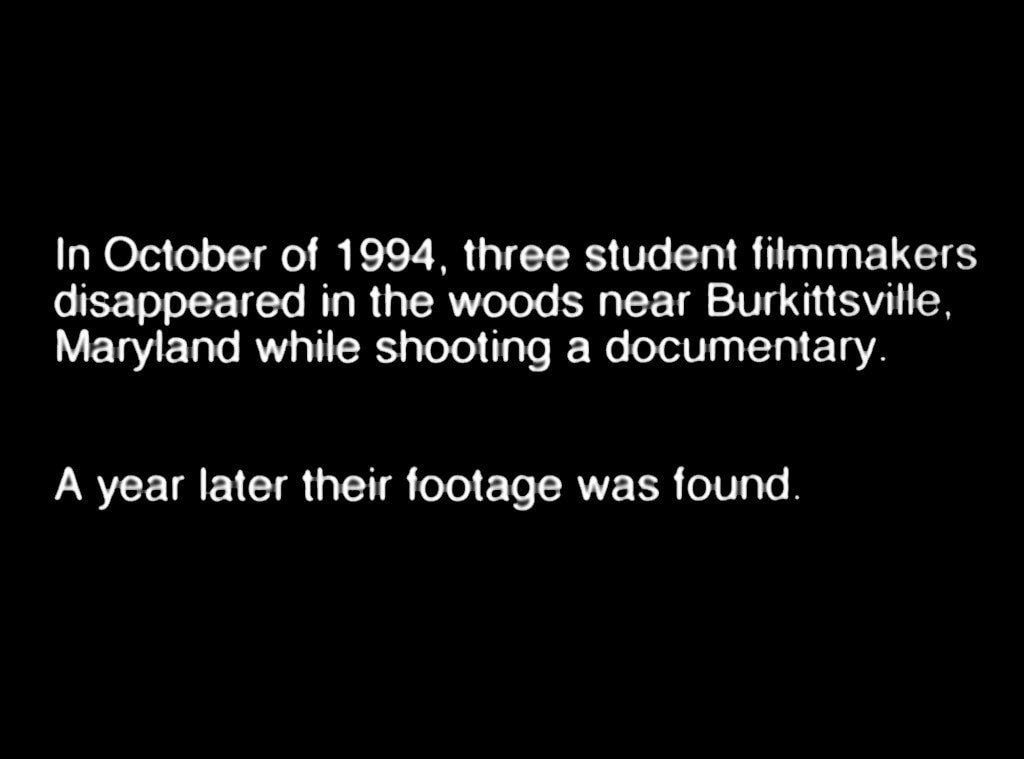

Fueled by a clever marketing strategy that presented the movie as footage discovered in the woods of Burkittsville, Maryland following an unidentified and presumably terrifying event involving three student filmmakers, The Blair Witch Project tapped into the kind of organic excitement that’s difficult to replicate nowadays.

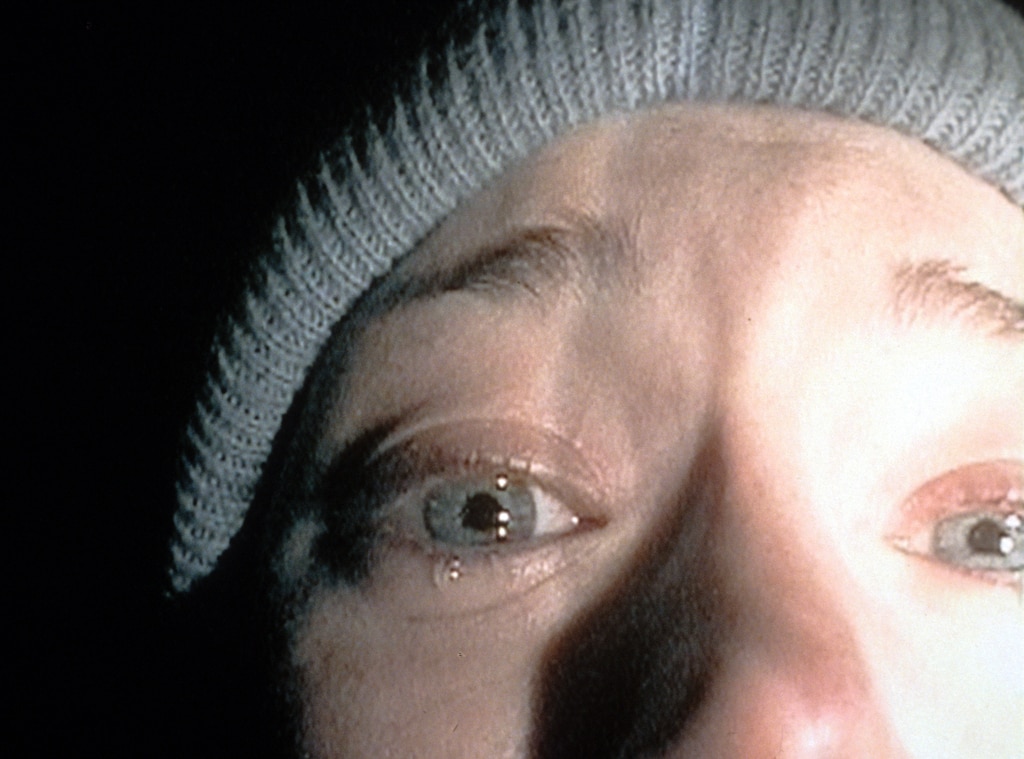

The film gave birth to an online realm of its own, featuring a “documentary,” titled “Curse of the Blair Witch,” which delved into the happenings depicted in the original movie, along with numerous follow-ups and satires. Notably, Heather Donahue‘s well-known monologue filmed up-nose became a popular target for mockery. Furthermore, a fresh sequel is on the horizon, poised to send shivers down your spine once more.

Upon its debut, it not only sent shivers down spectators’ spines but also left them puzzled about the events unfolding. Sitting in the cinema, many viewers understood they weren’t witnessing real-life danger, yet remained unsure of the storyline—making The Blair Witch Project a film worth seeing twice to catch what might have been missed initially.

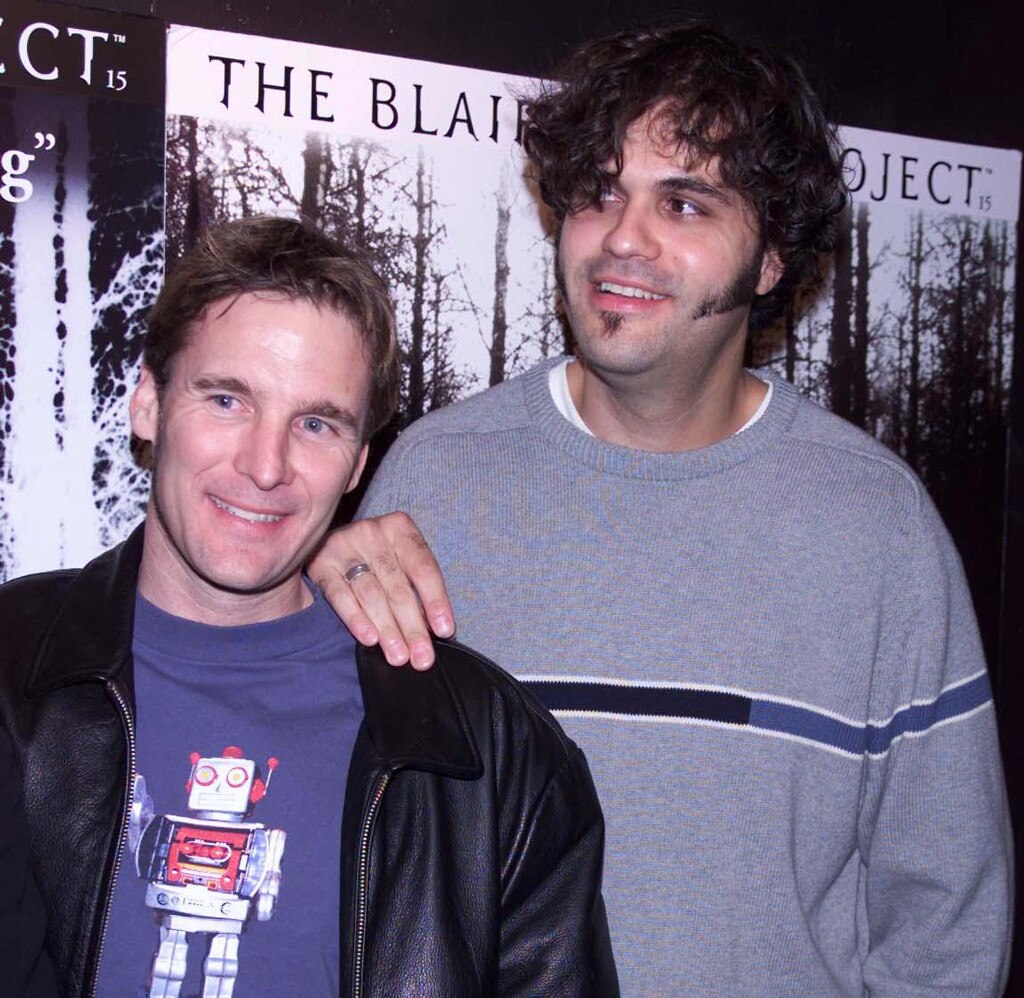

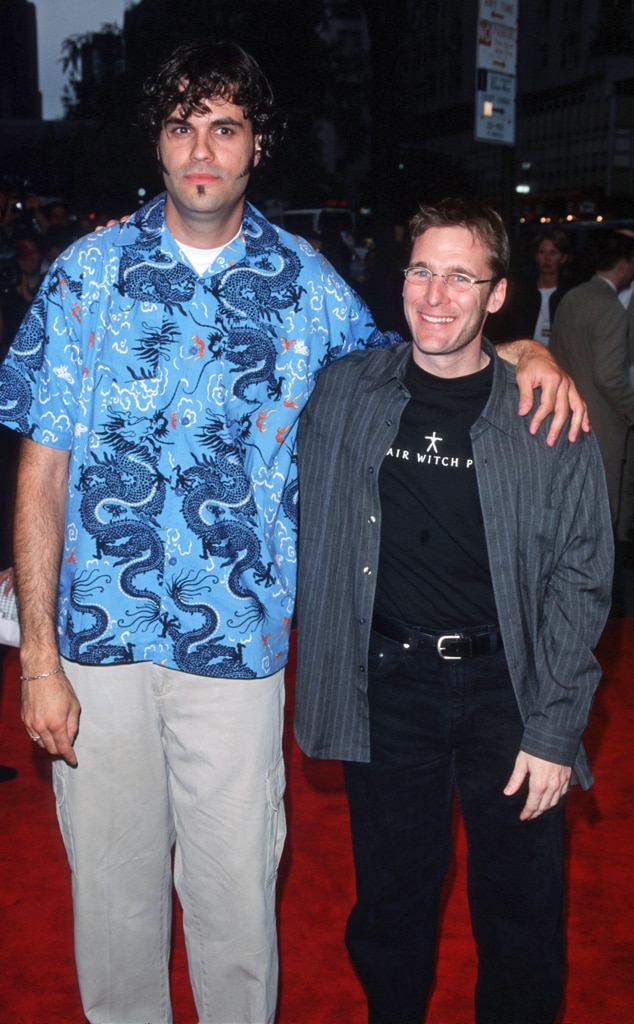

In a 2014 interview with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences’ Academy Originals, director Daniel Myrick expressed that our work on it was satisfactory and well-received, sparking intense interest among viewers who embraced it wholeheartedly. This response led to the emergence of a new genre in found footage films.

Included my fellow director, Eduardo Sánchez, who commented, “It illustrates that a compelling concept can remain just as grand as any production from Tinseltown.”

In honor of its 25th anniversary, read on for all the behind-the-scenes secrets…

Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez crossed paths as film students at the University of Central Florida’s School of Film around 1993. During their discussions about horror movies, they lamented the scarcity of truly chilling films. This led them to ponder the unsettling scenario where a group might discover a house in the woods and, despite knowing something sinister was occurring within, would feel compelled to enter.

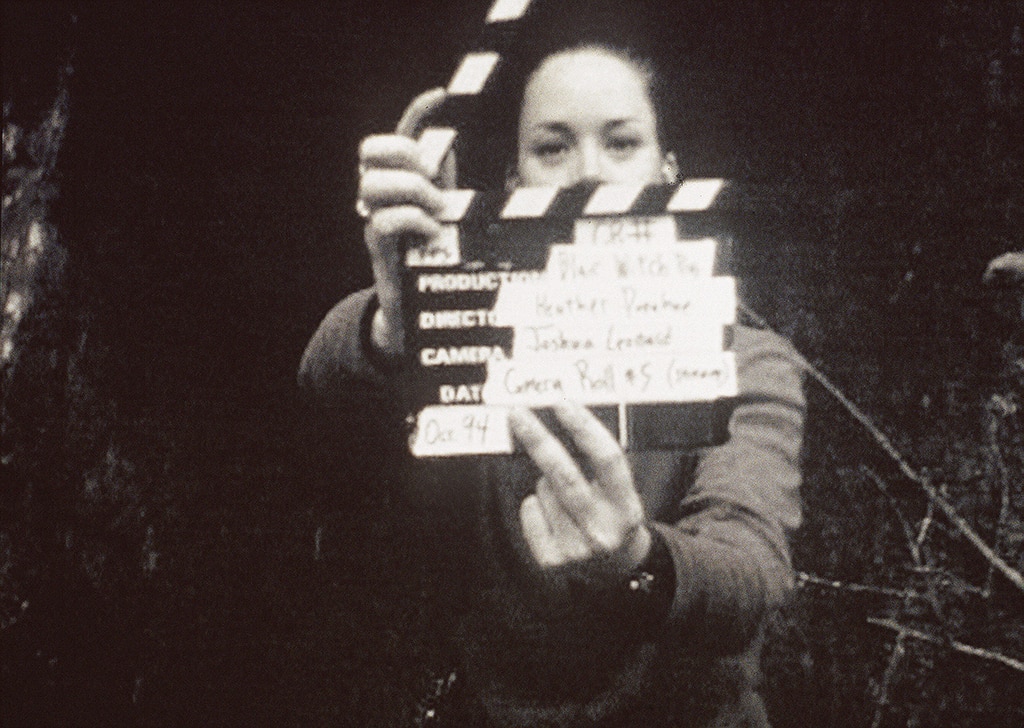

For several years following, they developed the legend of the Blair Witch, recruited some relatively unknown actors capable of improvisation, raised funds, and production began in October 1997. The movie was filmed over eight days at locations such as Germantown, Md., Seneca Creek State Park, and the Griggs House within Patapsco Valley State Park. Filming concluded on Halloween.

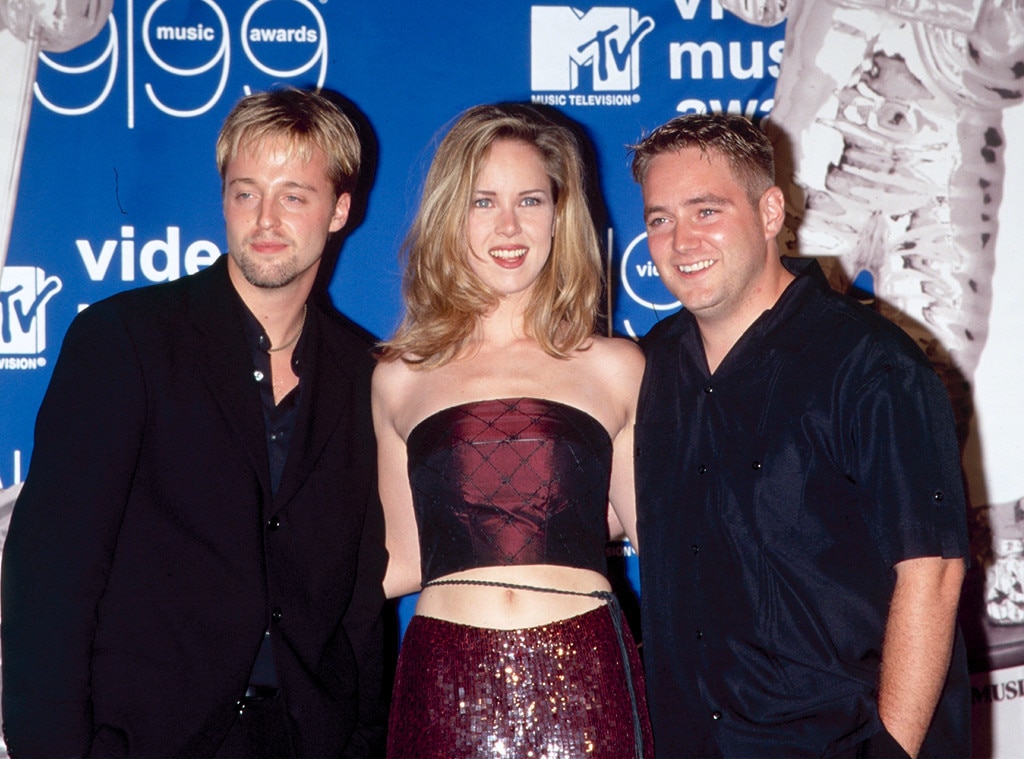

In 1994, the documented year, “student filmmakers” Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard embarked on a hike in the Black Hills of Burkittsville but failed to return. A year later, their footage was discovered.

In an interview with The Guardian in 2018, Myrick clarified a widespread misconception that the film required minimal effort. However, he revealed that it actually took two years of dedicated work to give the impression that it was filmed by only three students during a long weekend.

Initially, the characters Heather, Josh, and Mike experience normal events in the forest, but things soon take a strange turn. As revealed in both “The Blair Witch Project” and its companion documentary “Curse of the Blair Witch,” the backstory goes as follows: In 1785, a woman named Elly Kedward was accused of witchcraft in what is now Burkittsville, Maryland. She had been found pricking the fingers of children to draw their blood. Convicted at trial, she was banished into the woods and tied to a tree during winter’s depths. By the next winter, more than half of the town’s children had vanished.

1940 marked the beginning of a chilling mystery in the town, as children started vanishing one by one. A reclusive hermit named Rustin Parr emerged from the woods and announced, “I’ve completed my task.” Baffled townspeople couldn’t comprehend his statement, but when the police searched his cabin, they discovered the gruesome remains of seven missing children. In the trial that followed, Parr confessed to carrying out the killings under the instructions of an old ghostly woman.

As a lifestyle expert, let me share an intriguing tale I recently came across. A fellow lady confided in Heather about a chilling legend she’d heard. It goes like this: Two hunters went out camping and mysteriously vanished without a trace.

The filmmakers later return to their campsite to find three piles, one for each of them.

In my role as a lifestyle expert, let me share some insights about an intriguing filmmaking approach I recently encountered. A duo named Myrick and Sánchez crafted a compelling screenplay spanning approximately 35 pages, meticulously detailing the journey of their characters. However, instead of scripting the dialogue word for word, they opted to leave room for improvisation – a daring move that adds an authentic, spontaneous feel to their work.

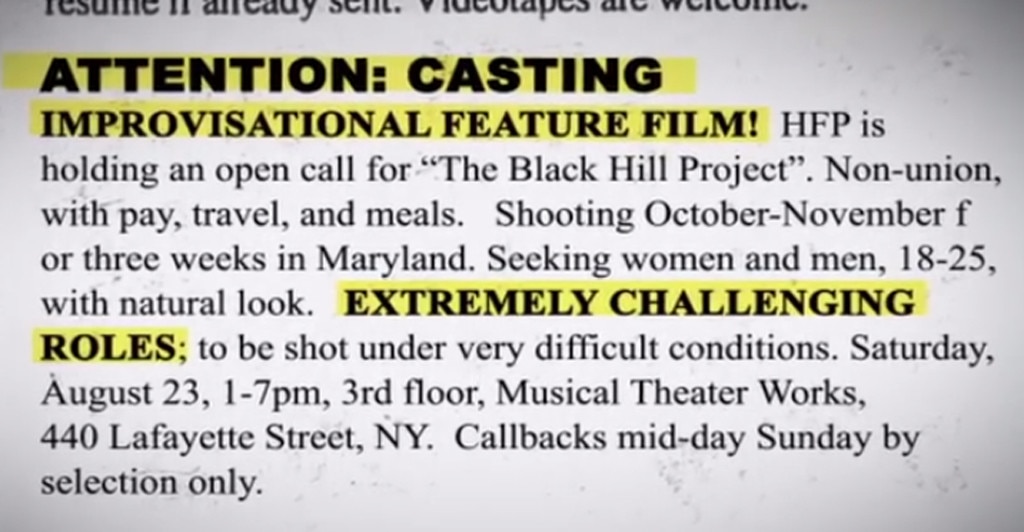

In a 2016 interview with Vice’s Broadly, Donahue – a founding member of an improv group and experimental theater company in New York – recounted an audition experience. During the improvisation session, she was given a challenging scenario: “You have spent half of your prison term for murdering your child. Why should we let you go free?” In response, she bravely stated her opinion, saying, “I don’t believe you should.” It seems that she was the only woman who spoke up during the audition, and as a result, she landed the role.

As a seasoned lifestyle connoisseur, I stumbled upon an intriguing open casting call in Backstage Magazine for an “IMPROVISATIONAL FEATURE FILM!” codenamed “The Black Hill Project.” The enticing advertisement hinted at “EXTREMELY CHALLENGING ROLES,” to be filmed under exceptionally demanding circumstances. I couldn’t resist the allure and decided to throw my hat in the ring for this unique opportunity.

Myrick stated to The Week that “[Heather] provided us with a fantastic mix of intelligence, quick thinking, and extraordinary determination that our actors required to persevere through the challenging situations we anticipated. He teamed her with Josh, who had expressed his interest in the film from the start, and Mike Williams, whom they discovered during auditions in New York. These three had an amazing rapport; a good balance of humor and tension, along with the ideal appearance.”

As a dedicated follower, I found myself immersed in a unique production where the filmmakers craftily distributed false promotional flyers for nonexistent events around Burkittsville to add authenticity to our “project.” To prepare for my role, Donahue delved into the intricacies of witchcraft and self-preservation in the wilderness. Given his prior experience with camera work, it was only logical that Leonard was tasked with capturing our scenes, while Williams took on the role as our sound technician.

According to Donahue, he did his best to scare himself before we even arrived at the destination. (The Week)

Added Williams, “All they told me was that they wanted me to be the one that was more scared.”

With the help of GPS trackers, filmmakers guided Donahue, Leonard, and Williams to various spots, enabling them to exchange filmed footage using 16mm cameras and receive new directives. As Gregg Hale, the producer, explained to The Week, “The actors were unaware they were in the woods.” We remained concealed, constructed secret vantage points for observation, and stayed close to them without their knowledge. Although we were present, they didn’t realize our presence.

In simpler terms, Myrick explained to Broadly that the strange noises and other occurrences were simply them creating a scene in the forest. They placed rocks near tents and hung stick figures as part of their setup. Essentially, they orchestrated a 24-hour-long theatrical production for the participants, complete with shaking tents, sounds of children playing, nighttime noises, and leading them to an unusual house at the end – all in a way that made it seem like they were living the Blair Witch story.

In this scenario, the actors stayed in tents and reduced their food intake every day, mimicking what they might do if they were genuinely camping and had become lost. However, Donahue clarified to The Week that they didn’t have to resort to survival tactics like skinning squirrels. Instead, it was more like a regular park where they occasionally paused filming for families passing by on their bicycles.

Leonard quipped to Broadly., “I was probably too stoned to be scared.”

One rainy evening when they couldn’t contact the directors or sleep in their wet tents due to continuous downpour throughout the day, the trio decided to leave and approach the nearest house. To their surprise, the residents were kind enough to welcome them inside and offered hot cocoa. As a result, they spent that night at a hotel instead.

In their acting roles as “Heather,” “Josh,” and “Mike,” the actors employed a secret term, “taco,” signifying a brief pause from their characters. However, this word had an unexpected consequence – it left them craving real tacos instead.

As the dedicated director, Donahue was privy to more details about the Blair Witch than her fellow actors. Consequently, when Leonard and Williams posed queries, they were essentially seeking insight from her.

Why is Heather so adamant about keeping the camera rolling, despite the fact that it’s clear they’re lost in the forest, and even after Josh and Mike keep urging her to switch it off?

In an interview with Broadly, Donahue shared that two years prior, he had worked on a student film with a confident young female director. He pondered, “Which woman would persist in recording during challenging situations when most people would stop?” Recognizing the need to portray an exceptional character, he decided to push himself to this driven extreme.

Initially, it was Mike – the one who would laugh uncontrollably when they got lost – who was supposed to depart, but due to frequent arguments between Josh and Heather, Sanchez and Myrick opted to eliminate Josh first. As stated in my note, “Tonight, when everyone retires for sleep, remain awake. Once you’re certain they’re asleep, exit the tent. If anyone stirs, inform them you need to relieve yourself.”

At the movie’s thrilling end, Josh seemingly vanishes, leading Heather and Mike to believe they heard him. According to Leonard, “Ed, Dan, Gregg, and perhaps Ben Rock [the production designer] were there, ready for me with flashlights. They declared, ‘You’re dead,’ then treated me to a delightful dinner at Denny’s.” (Both Heather and Mike enjoyed a meal at Denny’s following their own grim encounters.)

As a fervent admirer, let me express my sincere apologies. In retrospect, I confess my ignorance was blinding… What on earth is this? My heart races as I contemplate closing my eyes; the thought of opening them again is equally terrifying. It seems our fate hangs in the balance out here.

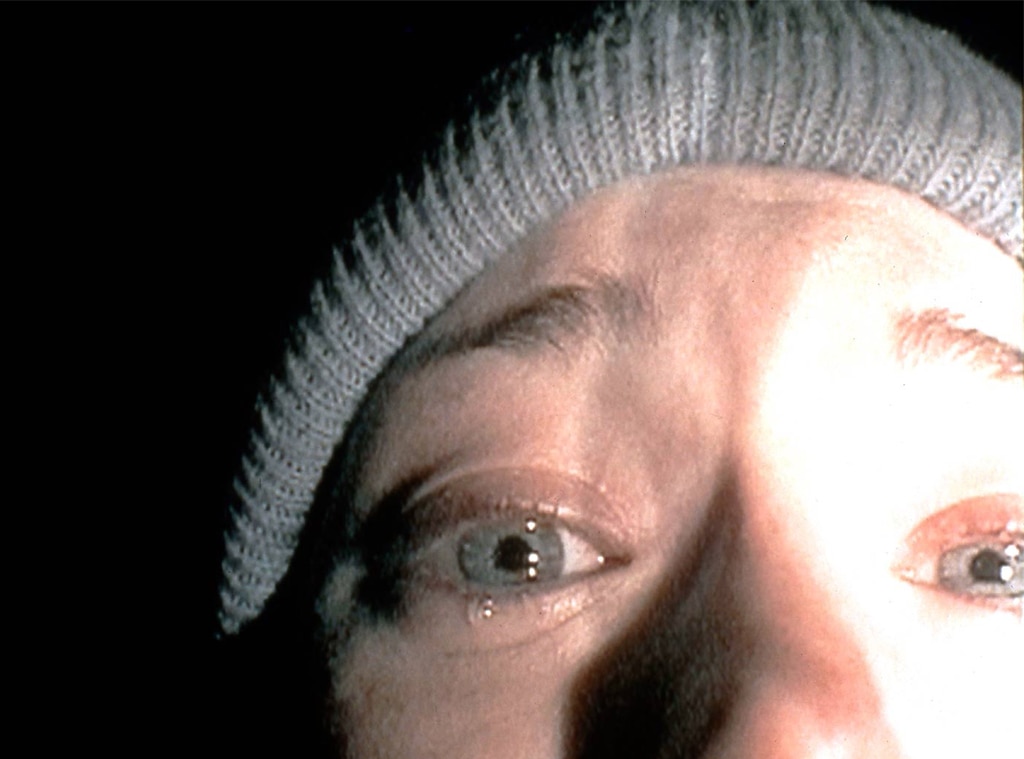

Heather spontaneously delivered her chilling closing speech, during which she conceded that it seems their situation might be irreversible (since Josh has left), and expressed regret to all their mothers for leading them into such a predicament.

In an interview with The Week, Donahue expressed her immense pride over a moment in her film career that deviated from typical actress behavior. She described it as an emotional outburst filled with snot, unattractiveness, truth, and messiness – a raw, sloppy display of genuine sadness seldom seen on screen.

In a heart-pounding climax, as I scoured the house for Josh alongside Heather and Mike, every second felt like an eternity. We became momentarily separated, and when I found Heather, she was standing next to a trembling Mike with his back against a wall – a chilling premonition hinting at imminent danger for whoever else was in the room. Contrary to the tension, this suspenseful scene was not captured in a single terrifying take.

Heather was making loud, frightened noises in the house, giving the impression she might be going crazy, but this scene was filmed multiple times across two days – this part was quite conventional for the movie, according to Myrick’s recollection to Broadly. To ensure safety and proper setup, we had to meticulously arrange and rearrange the house, being mindful not to injure anyone. The atmosphere was more controlled than one might think. The genuine fear seen on their faces is simply a part of their acting performance.

Initially, Sánchez and Myrick intended to create a documentary using over 80 hours of footage from Leonard, Donahue, and Williams, incorporating elements like actors portraying the missing filmmakers’ parents. However, it was only after they started editing that they realized the final production would solely consist of what the trio had actually captured on camera.

The official website for “The Blair Witch Project” presented its content in a grave and authentic manner. It contained a chronology of events preceding the trio’s disappearance, along with fictional news interviews about the case and simulated police reports. Fans of the Blair Witch were drawn to discuss the legend and the fate of Heather, Josh, and Mike online as if they were investigating a real-life crime. Before the movie was even released, 10,000 people had signed up for the mailing list.

Williams reminisced to The Week about the early days of the internet, saying “The internet was fresh and unfamiliar! So when you’d come across something online, you’d think ‘Ah, that must be accurate. I found it on the internet.’ It was much like how people trusted newspapers back then. You accepted what you read.”

As a film enthusiast who has attended numerous film festivals over the years, I must say that the story of “The Blair Witch Project” is one that stands out among the rest. Having witnessed its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 1999, I can attest to the electrifying atmosphere that surrounded the mysterious project. The actors’ absence from promotional materials and the subsequent rumors of their deaths only added to the intrigue surrounding the film.

As a devoted follower, I’ve observed that even after folks realized it was merely a film, many continued to believe it depicted actual events.

Twitter didn’t create outrage culture.

“Shortly after the movie came out, there was a reaction against it from some viewers,” Sánchez shared with Broadly. “They weren’t prepared for the kind of film it turned out to be. They anticipated a traditional horror movie instead. Since it didn’t conform to the conventional horror format (as Blair Witch doesn’t), people began criticizing it, saying something like, ‘They think we’re gullible.’ However, by then the movie had already made significant profits and gained success—by that stage, it was more about the money than the criticism. But as creators, it still stung us quite a bit.”

Myrick commented, “Publicity often follows a pattern: oversaturation and excessive promotion can lead to it becoming trendy for people to dislike what seems popularly liked.”

As a lifestyle expert, I can tell you from personal experience that when Leonard Donahue, William Leonard, and I (Williams) were working together on that blockbuster film, we formed a strong bond. However, once the dust settled and the movie’s unprecedented success became evident, we found ourselves grappling with the intense spotlight that came our way. It was an unexpected challenge we had to navigate, but one that ultimately made us stronger as individuals.

Williams expressed it this way: “Let me put it another way, it was quite frightening,” he stated. “In the midst of it all, things seemed to spiral out of control so quickly that I felt disoriented. They were tugging at me from every direction…I had a fantastic experience with it, but let me tell you, Sundance was as much excitement and attention as I could handle comfortably. Afterwards, I wasn’t comfortable for quite some time.” Donahue added, “Picking the worst part is tough. It was the anger directed at me just for being alive.”

In 2018, Leonard shared with The Guardian that there are individuals who remain skeptical about it being a work of fiction. Occasionally, he muses that perhaps Artisan would have found greater contentment if we truly had perished instead.

Despite receiving much positive criticism, The Blair Witch Project was also nominated for the Worst Picture award at the Golden Raspberry Awards, with Donahue receiving the Razzie Award for Worst Actress. In an interview with Broadly in 2016, she explained, “I believe that was partly due to the character being evaluated, rather than the acting itself. The character was a highly driven woman who didn’t wear mascara and appeared on camera as early as 1999.”

In my experience as a lifestyle guide, I’ve often emphasized that a heap of stones isn’t naturally terrifying. It’s our minds that conjure up fear based on imaginary scenarios, much like an actor immersing themselves in their role.

In a positive turn of events, Myrick, Sánchez, Hale, and co-producer Robin Cowie received the John Cassavetes Award in 2000 at the Independent Spirit Awards. This award recognizes debut features that were produced for under $500,000. Additionally, they were both recognized as Most Promising Producer in Theatrical Motion Pictures at the prestigious PGA Awards.

In The Blair Witch Project, all three main actors have gone on to act in other projects, but among them, only Joshua Leonard continues acting as a regular profession.

Since 2008, Donahue has not added any acting roles to her resume. Instead, she penned a memoir titled “GrowGirl,” published in 2012, which recounts her life following the Blair Witch Project and her subsequent foray into the marijuana-growing industry. In the book, Donahue expressed that the successful marketing campaign of the Blair Witch film may have led people to believe she and her co-stars were merely ordinary kids, making it challenging for her to be taken seriously as a legitimate actress when seeking work afterward.

In 2018, Williams made an appearance on the CBS series FBI, marking his return to television nine years following a guest role on Law & Order: SVU in 2009. Five years prior, The Week magazine reported that he was employed as a school counselor and was also teaching acting.

As an ardent aficionado, let me caution you all: Be wary of the studio that’s chasing a blockbuster’s tail. The sequel to the chilling legend, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, was hastily crafted and released in October 2000, raking in an astounding $47.7 million at the box office. Yet, it only set them back a reported $15 million to create this cinematic misstep—a stark contrast to its critical reception. On Rotten Tomatoes, it scored a dismal 14%, while Metacritic gave it a paltry 15/100. The original masterpiece, on the other hand, boasts an impressive 87% on Rotten Tomatoes and a respectable 81/100 on Metacritic.

The spell was broken, just like that. Director Joe Berlinger said that his vision for the film—about tourists who go to Burkittsville after seeing The Blair Witch Project—was compromised in postproduction.

In 2016, Berlinger told Deadline, “My director’s cut might not have necessarily received a more favorable response from critics, but at least I could have felt proud of the film for showcasing my vision. If that version had been disliked, it would have hurt less because it would have reflected what I wanted to present.”

As a movie enthusiast and someone who has followed the career of many directors over the years, I must admit that I was initially skeptical about the success of “Blair Witch 2.” The original film had left such a lasting impression on me, and I was worried that its sequel might not live up to expectations. However, after hearing the director’s perspective on the matter, I have come to realize that my initial assumptions were mistaken.

Although they are recognized on IMDb as executive producers and character creators for Book of Shadows, Myrick and Sánchez chose to disassociate themselves from the project otherwise. They had a desire to create a prequel but also wanted some time to pass, which didn’t align with the studio’s strategy. As a result, they willingly relinquished their roles in the project.

As a lifestyle expert, I had high hopes for the 2016 film titled “Blair Witch,” marketed as a direct sequel to the original. However, it didn’t receive much critical acclaim, and despite being slicker than its predecessor, it still underperformed at the box office with a total gross of $45 million. The concept remains similar: instead of Heather, her brother James leads a group into the woods to uncover the truth about her disappearance, with his friend documenting their journey on camera. The most chilling part is the prologue, where you’re warned that the footage you’re about to watch was recovered from memory cards and DV tapes found near Burkittsville, Maryland in the Black Hills Forest on May 15, 2014.

That doesn’t get old.

The reported cost of making the movie has fluctuated, with $60,000 often mentioned as the figure – but much like crafting a film to appear entirely improvised, it’s actually a bit more intricate than simply throwing around a number.

In 2009, Sánchez revealed to Entertainment Weekly that the initial budget for the film ranged from approximately $20,000 to $25,000. However, once post-production costs were factored in, like making a print and sound mixing at Sundance, the budget increased to around $100,000. Later, the studio added about $500,000 to it, requiring a new sound mix and a less ambiguous ending. Thus, Sánchez estimated that the final theater budget was between $500,000 and $750,000.

They stuck with their original ending in the meantime.

In 2018, Myrick shared with The Guardian that the initial budget for filming “The Blair Witch Project” was roughly $35,000. However, when all costs were considered, the final cost came up to approximately $300,000.

No matter the exact amount, it earned a staggering $248.6 million globally and continues to be among the most financially successful independent films ever made, boasting one of the largest profits on an original investment.

Although many cinema-goers found The Blair Witch Project unique, it wasn’t the very first found-footage film. Movie enthusiasts at Bloody Disgusting suggest checking out 1989’s UFO Abduction, which was made on a budget of $6,500 and claimed to be a home recording of an alleged 1983 alien invasion during a child’s birthday party in Connecticut. However, it’s the 1980’s film Cannibal Holocaust, about a documentary crew who vanished in the Amazon and filmed their own grisly deaths before disappearing, that is often given credit as the first found-footage movie.

Currently, the collection of found-footage films is quite extensive and continues to grow. However, the Paranormal Activity series stands out by opting for a stationary surveillance style rather than relying on the unsettling approach used in The Blair Witch Project, which was groundbreaking at its inception.

Leonard shared with Broadly that we owned a $300 camera and another one that was given to us. It amuses him when high-end studios intentionally make something appear low-quality visually and acoustically. He finds it humorous, but recognizes that it can be an effective storytelling method for certain narratives.

According to Donahue, their experience was undeniably raw and unconventional filmmaking, a style that’s hard to achieve when you have a catering table and strict safety measures constantly available. This aspect presents a difficulty for many modern found-footage films. The essence of the wildness or the Internet during that time can never truly be replicated.

Read More

2024-07-30 23:24