As a child, my house was consistently bustling with the background noise of several computers. Frequently, I would enter our study room to find computer components strewn across a table, as my engineer father tinkered with and upgraded PCs to cater to our preferences.

For a while, Apple played a role in our narrative, but as the ‘walled garden’ approach gained prominence, we found ourselves increasingly distancing ourselves from Apple computers. Over time, we transitioned towards using more Microsoft products instead.

During a conversation with my father, I discovered some fascinating insights into the specific transition point when Apple shifted from manufacturing open computers to closed systems. This captivating account held particular significance for me because I experienced it during my formative years, but didn’t quite grasp it then. Now, I’d like to share this intriguing piece of history with you all.

Apple once offered open PCs, and this allowed my father to build one on a budget in the 80s

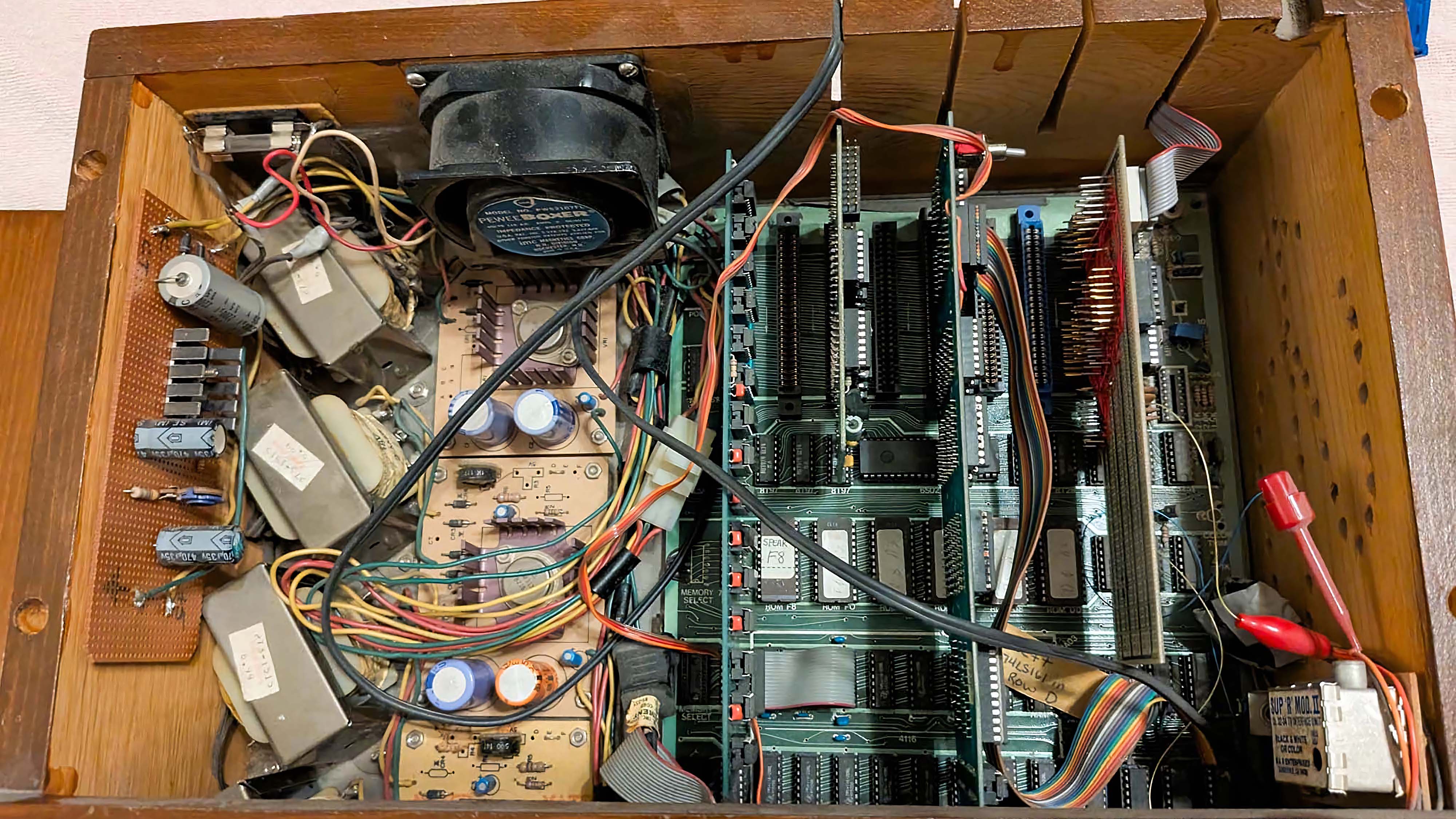

My father’s very first homemade computer was essentially a Frankenstein-like assemblage of repurposed Apple components, crafted back in 1982 – a time when personal computers were scarce and exorbitantly priced. Back then, my dad was a resourceful yet cash-strapped university student. When he got the chance to fix a damaged Apple II motherboard, he eagerly took it on.

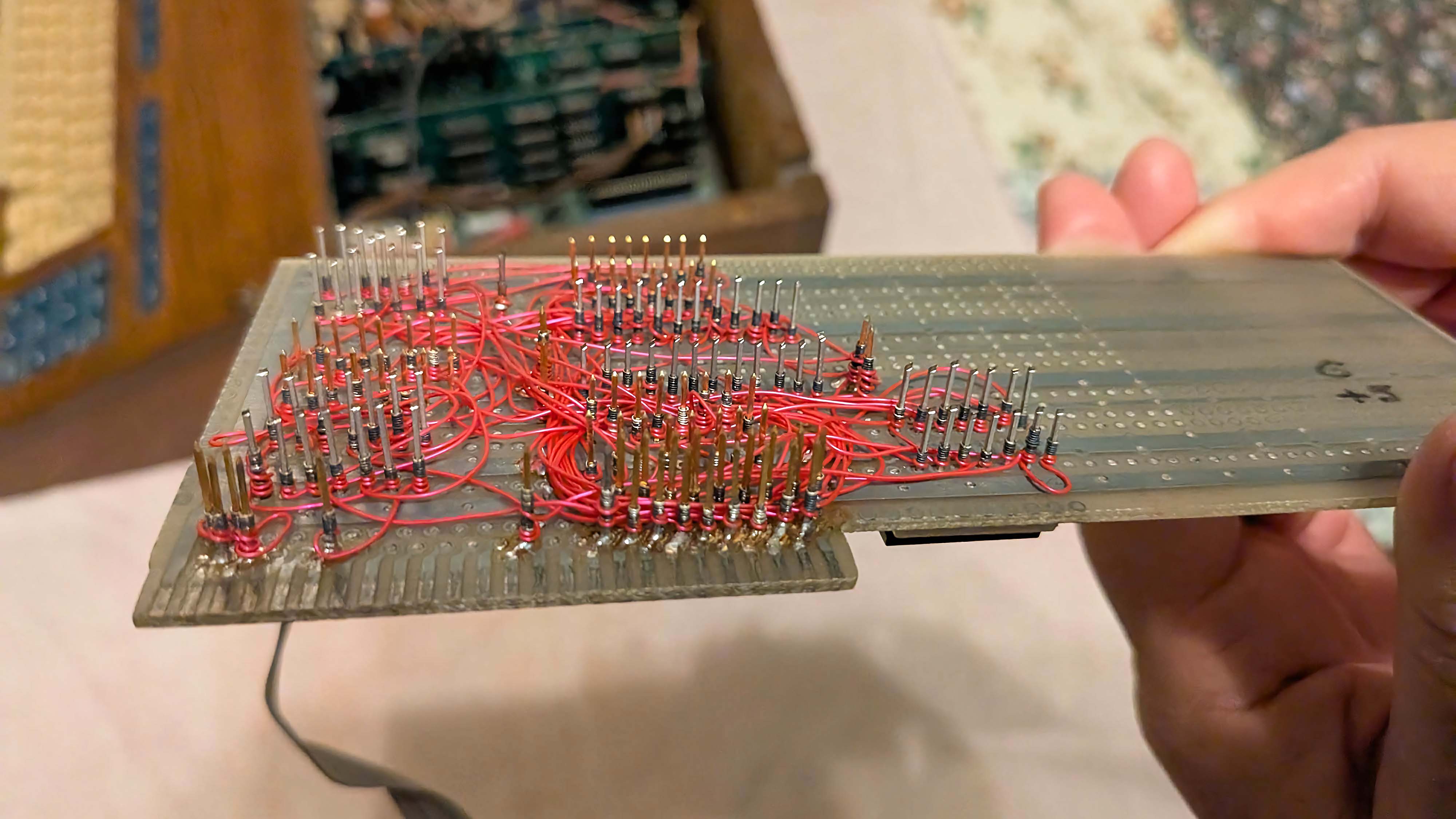

Initially, he removed any signs of previous use and connected numerous jumper cables to render the motherboard functional. In order to assemble the remainder of his computer, he eventually searched through surplus outlets, catalogs, and Radio Shack to compile a functional machine. Frequently, he had to attach or solder parts on his own.

In those days, computer components were less common, so he frequently built his own systems himself. On separate occasions, he encountered individuals disposing of an ancient monitor and a printer, which he was fortunate to obtain. This Apple device provided him with the liberty to create custom cards, utilize PROM (Programmable Read-Only Memory) programmers, and connect various devices to tailor the PC according to his preferences.

In the past, Apple was flexible enough that individuals such as your father could dissect the underlying processes and personalize their devices. He even developed a custom EPROM to adapt a salvaged keyboard for use on what he named his “Frankenstein computer”.

When faced with a lack of funds for a case, he creatively turned to his college’s wood shop where he crafted a bespoke keyboard case that snugly fit his device. He then added ventilation holes in the shape of an “S” (representing Spear) on one side and designed it with a flat top to accommodate a monitor.

To sum up, he spent around $800 ($2,665 equivalent today) to construct his Frankenstein computer, which was substantially less expensive than a similar PC from 1982 that would have set him back by a staggering $2,400 ($8,034 equivalent today), a high price for the era.

Using the newly built computer, he could now work on a word processor and a spreadsheet software to finish his schoolwork, while most of his peers either used typewriters or handwrote their assignments.

Apple forces you to do it their way or no way.

In simpler terms, by the time I became old enough to learn computing, many years later, the same computer was still functional and operational. Among my earliest recollections are those of me playing Donkey Kong on it, with my small hands awkwardly navigating a keyboard that was built into a wooden frame, while the screen displayed an orange gorilla against a black background.

In simpler terms, unlike anyone else I knew, I had a unique computer. It was custom-made, thanks to its open design, which enabled my father to educate himself about computers and craft a device tailored to our specific requirements.

Apple put my family off its computers when the walled garden reared its head

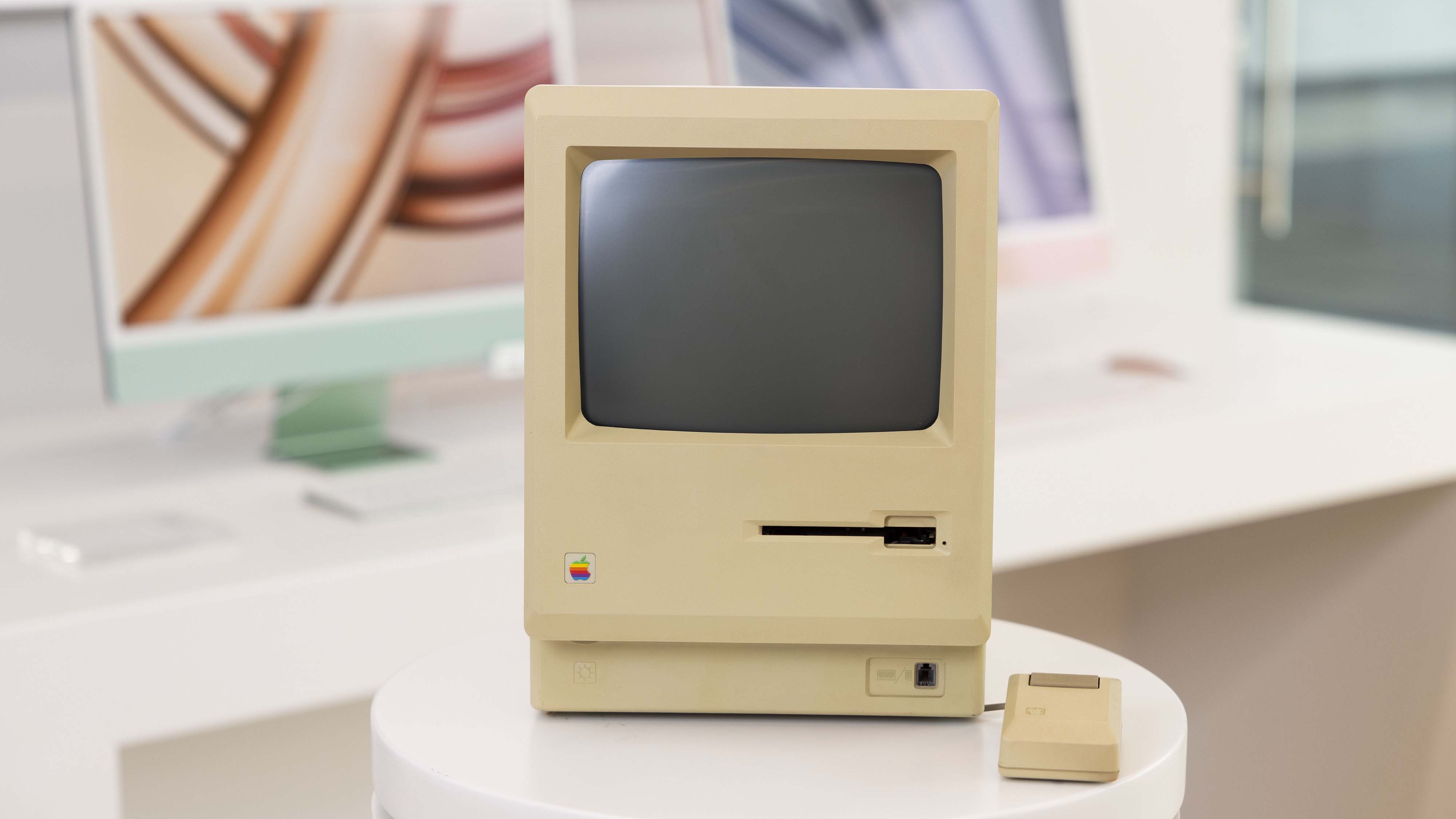

In the early to mid-90s, however, the situation shifted significantly following Apple’s launch of a novel Macintosh computer. Eagerly, my father brought this new device home, only to discover upon opening the package that the computer came factory-sealed – a departure from previous Apple PCs.

Indeed, he decided to open it, yet discovered that instead of having replaceable components in the motherboard, those parts were already soldered in place, which indicated they weren’t intended for user replacement.

During a deeper examination, it was found that the Macintosh relied on SCSI (Small Computer System Interface) for communication – a fresh, exclusive method distinct from the prevailing protocols of the era. Interestingly, Apple seemed reluctant to disclose the inner workings of this SCSI protocol, or perhaps lacked the ability to do so. As a result, computer enthusiasts, including individuals like my father, were unable to make improvements or modifications to this aspect.

That’s when Apple failed to retain him and several of his engineering colleagues, as he put it to me not long ago, “Apple insists on doing things their own rigid way, with no room for alternative approaches.

MS-DOS, Windows, and Linux to the rescue

Not long after, the Macintosh was often referred to as “the children’s computer,” a title my siblings and I claimed for playing simple games or creating Cool S designs in drawing software (90’s kids will recognize this). Simultaneously, unsatisfied with the Macintosh, our dad opted to purchase an IBM PC instead. This PC ran on MS-DOS and was both open and flexible, serving his needs more effectively while also piquing my interest.

In simpler terms, I often found myself immersed in a variety of captivating games such as DOOM, Duke Nukem, Commander Keen, Street Fighter, and others on that very computer. As he kept fine-tuning and personalizing it, I would spend numerous hours exploring these exciting titles.

Gradually, my dad accumulated computers that weren’t working properly and repaired them, resulting in a group of machines over time. Although I can’t pinpoint the exact moment, what I do remember is having a den filled with Windows 95 computers. I don’t have an exact count, but I spent countless hours playing Age of Empires II, creating art with MS Paint, and writing stories in Word in our makeshift home computer lab with my brothers.

My father appreciated the flexibility of Windows, as it allowed him to customize hardware components and software settings according to his preferences, rather than being limited by Apple’s design. Over time, this led him towards Linux, too.

Over time, I developed a liking for customizable tech devices, and I enjoy putting together my personal computers instead of buying pre-built ones. I may not be an expert like an engineer, but I regularly modify the equipment I possess to better fit my requirements. My experiences using Apple PCs as an adult have often felt cumbersome and exasperating in contrast.

The walled garden is not for people who like customization.

Forcing limitations pushes your user base away

Discovering the significance of when Apple’s “walled garden” affected my family was intriguing, leading to my father transitioning from an Apple PC user to a Microsoft PC user at that point.

The outcome of this decision significantly shaped my life, providing valuable insights into computer personalization. Above all, I strongly advocate for users having the power to control their technology, not vice versa, allowing them greater freedom in what they can and cannot accomplish.

While Windows might not be the ultimate choice for extensive customization, it certainly outshines Apple in terms of flexibility. Compared to Apple, Windows provides a less confined and more user-friendly experience, though it’s worth noting that Linux offers even more compatibility with various software solutions.

I’ll always fight to keep my PCs as customizable as possible.

Read More

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- Bitcoin or Bust? 🚀

- Embracer Group is Divesting Ownership of Arc Games, Cryptic Studios to Project Golden Arc

- Bitcoin’s Mysterious Millionaire Overtakes Bill Gates: A Tale of Digital Riches 🤑💰

- 7 Best Movies That Took A Franchise To Space, Ranked

2025-08-18 17:10