Markets

What to know:

- Traders on Polymarket were confident in Geert Wilders’ PVV winning the Dutch election until a late surge by D66 changed the outcome. 🎩💥

- Many traders held onto losing PVV bets due to conviction, while others profited from the unexpected rise of D66. 🤑

- The prediction markets reflected user biases, highlighting how conviction can lead to irrational trading decisions. 🧠🌀

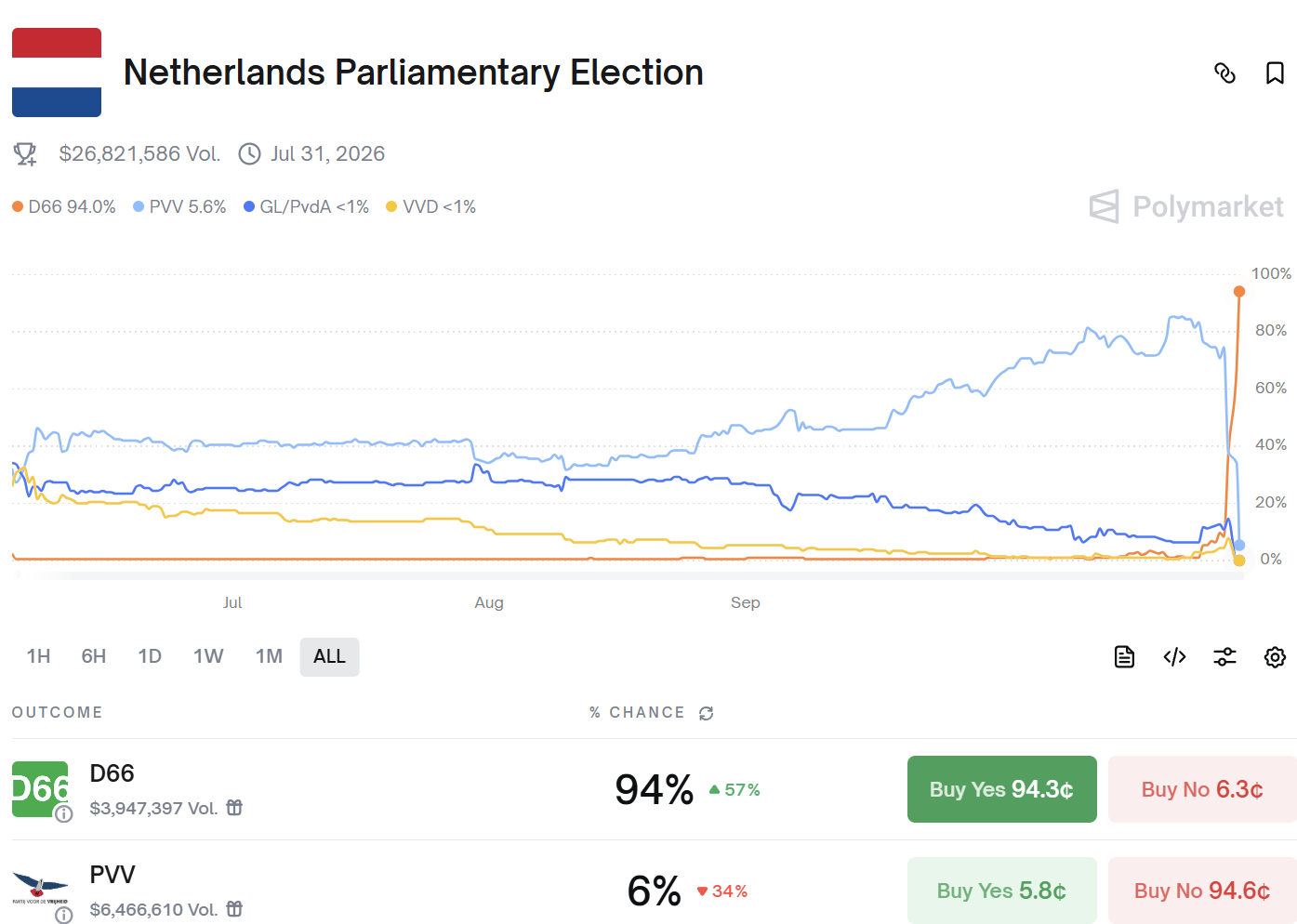

Until the final hours of the Netherlands’ Oct. 29 election, Polymarket traders were convinced Geert Wilders’ nationalist Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party for Freedom) would cruise to victory. 🏆😂

The market barely budged as Rob Jetten’s social liberal Democraten 66 (Democrats 66) climbed in every major poll. Then, within minutes of the first exit poll, D66 odds exploded from 5% to 100%, wiping out millions in overconfident PVV longs. 🚨💸

With 98% of votes counted, D66 and PVV were both projected to take 26 seats in the 150-seat lower house of parliament, Reuters reported Thursday. That’s a loss of 11 seats for PVV. 📉📉

Kalshi wasn’t much better, with traders overpricing Wilders’ PVV until election day. 🤷♂️

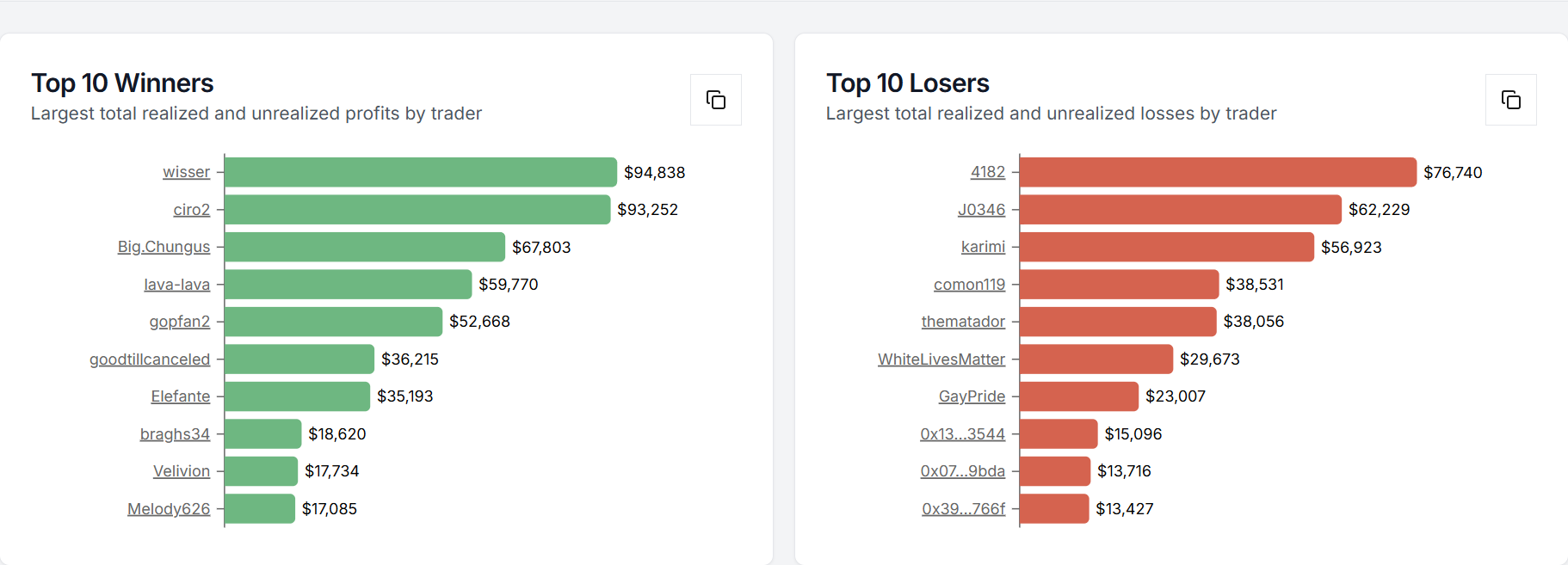

Data from Polymarket Analytics suggests the markets became a test of conviction rather than foresight as traders clung to losing PVV bets out of belief. Many held static positions for weeks while a smaller group of data-driven participants quietly profited from the late D66 surge. 🧩🤑

During the recent U.S. presidential election, all sorts of theories emerged about why Polymarket was giving a premium to now-President Donald Trump. Perhaps it was the participation of crypto holders, who tend to lean right. 🧠💸

One theory was that foreign money was trying to influence the vote by skewing markets. This theory was amplified when a French national using the handle “Theo” spread out pro-Trump and pro-Republican bets over a number of accounts. 🇫🇷🗳️

Theo, it turned out, had no political agenda, as he told the Wall Street Journal. Instead, the self-described wealthy banker determined national polling had gaps and instead commissioned his own, which involved pollsters asking respondents who they thought their neighbors would vote for. 🧪📊

The survey confirmed his thesis that the polls were wrong about Trump’s chances of victory, and he was confident enough to put $30 million in. 💸🔥

But for the Dutch election, there was no Theo. There were lots of conviction traders who acted as effective counterparties with exit liquidity. 🤝📉

Accounts like “WhiteLivesMatter” – whose username reflects their political views – poured tens of thousands into PVV “yes” contracts and never flinched, even as Ipsos and Peil.nl polls shifted decisively toward D66. 🧠✊

The positions sat unchanged for weeks, according to Polymarket Analytics. It wasn’t lack of information that doomed them, but a refusal to process it. 🧠🚫

That static posture contrasted sharply with traders like “Wisser” and “ciro2”, who moved early on late polling data and made six-figure profits from the same volatility that crushed the PVV faithful. These participants used the market as a rational actor would, attempting to make money with trades, not a scoreboard for ideology. 🧮💰

In the end, the prediction markets worked as mirrors, not predictors, reflecting the biases of their users. Where Theo used polling to challenge consensus, some traders ignored it entirely. 🪞👁️

In a market with thin liquidity, the result was a real-time experiment in how markets can be rational in theory yet irrational in practice, especially when conviction outweighs curiosity. 🧠🌀

Read More

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- 10 Most Brutal Acts Of Revenge In Marvel Comics History

- Katy Perry and Justin Trudeau Hold Hands in First Joint Appearance

- XRP: Will It Crash or Just… Mildly Disappoint? 🤷

2025-10-30 13:01