Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how ring-like structures within protoplanetary disks influence the movement of planets, leading to varied migratory fates.

Hydrodynamical simulations demonstrate that gas bumps can cause Jupiter-mass planets to migrate outward while trapping super-Earths within the disk.

The prevalence of rings and gaps in protoplanetary disks presents a challenge to fully understanding planet formation and dynamical evolution. This research, ‘Planet Migration in Protoplanetary Disks with Rims’, utilizes hydrodynamical simulations to investigate how planetary migration is influenced by these disk structures. Our findings reveal a mass-dependent migration pattern: Jupiter-mass planets tend to migrate away from bright rings, while super-Earths become trapped within them, potentially explaining observed planetary distributions. Could this mechanism account for the observed dearth of super-Earths within the density gaps of protoplanetary disks, and further refine our understanding of planetary system architectures?

The Birth of Worlds: A Protoplanetary Dance

Around newly formed stars, vast, flattened structures known as protoplanetary disks represent the birthplaces of planets. These disks aren’t simply inert clouds; they are dynamic whirlpools composed of gas – primarily hydrogen and helium – and microscopic dust grains. Gravity draws this material into a rotating disk, with the central star steadily accreting material while the remaining dust begins to collide and coalesce. Over time, these collisions lead to the formation of planetesimals – kilometer-sized bodies – which then gravitationally attract more material, ultimately growing into the planets observed orbiting stars throughout the galaxy. The composition and structure of these disks-influenced by factors like distance from the star and the disk’s overall mass-play a pivotal role in determining the types of planets that eventually emerge, offering clues to the incredible diversity of exoplanetary systems discovered in recent years.

The remarkable variety of exoplanetary systems – from scorching “hot Jupiters” orbiting incredibly close to their stars to small, rocky worlds nestled within habitable zones – necessitates a deep comprehension of protoplanetary disk dynamics. These swirling disks of gas and dust aren’t uniform; turbulence, gravitational instabilities, and magnetic fields all contribute to complex processes that sculpt the raw material into planets. Variations in disk composition, mass, and lifetime, coupled with the interplay of these forces, determine the types of planets that ultimately form. Consequently, detailed modeling and observation of these disks provide crucial insights into the conditions that led to the diverse planetary architectures observed throughout the galaxy, helping scientists understand why some stars host numerous planets, while others remain solitary, and why planetary systems can look so drastically different from $our$ own.

Early attempts to model the evolution of protoplanetary disks, while foundational, often presented a simplified picture of a remarkably complex system. These initial models frequently assumed a smooth, uniform disk, overlooking the inherent instabilities that arise from gravitational interactions, magnetic fields, and the very physics of fluid dynamics. Consequently, they struggled to accurately reproduce observed features like spiral arms, gaps, and the formation of planetesimals. The disks aren’t static; they are subject to turbulence – chaotic, swirling motions – that dramatically influences the distribution of dust and gas. This turbulence, and the associated heating and mixing, wasn’t adequately captured in earlier simulations, leading to discrepancies between theoretical predictions and astronomical observations. Recognizing these limitations spurred the development of more sophisticated computational techniques and theoretical frameworks capable of incorporating these crucial, yet challenging, physical processes.

Early attempts to model protoplanetary disks, while foundational, proved inadequate in capturing the full complexity of planet formation. These initial simulations often predicted disk lifetimes and planet compositions that didn’t align with observational data of both nearby and distant exoplanetary systems. The discrepancies arose from a simplification of key physical processes; turbulence, magnetic fields, and the gravitational interactions between dust grains were often either omitted or crudely approximated. Consequently, researchers turned to developing more computationally intensive and theoretically robust frameworks, incorporating magnetohydrodynamic effects and $N$-body simulations to accurately represent the intricate dance of particles and gases within these swirling disks. This push for greater sophistication enabled a more realistic exploration of disk instabilities, planet migration, and the ultimate architecture of planetary systems, bridging the gap between theory and the observed diversity of exoplanets.

Turbulence and Trails: Sculpting Orbital Paths

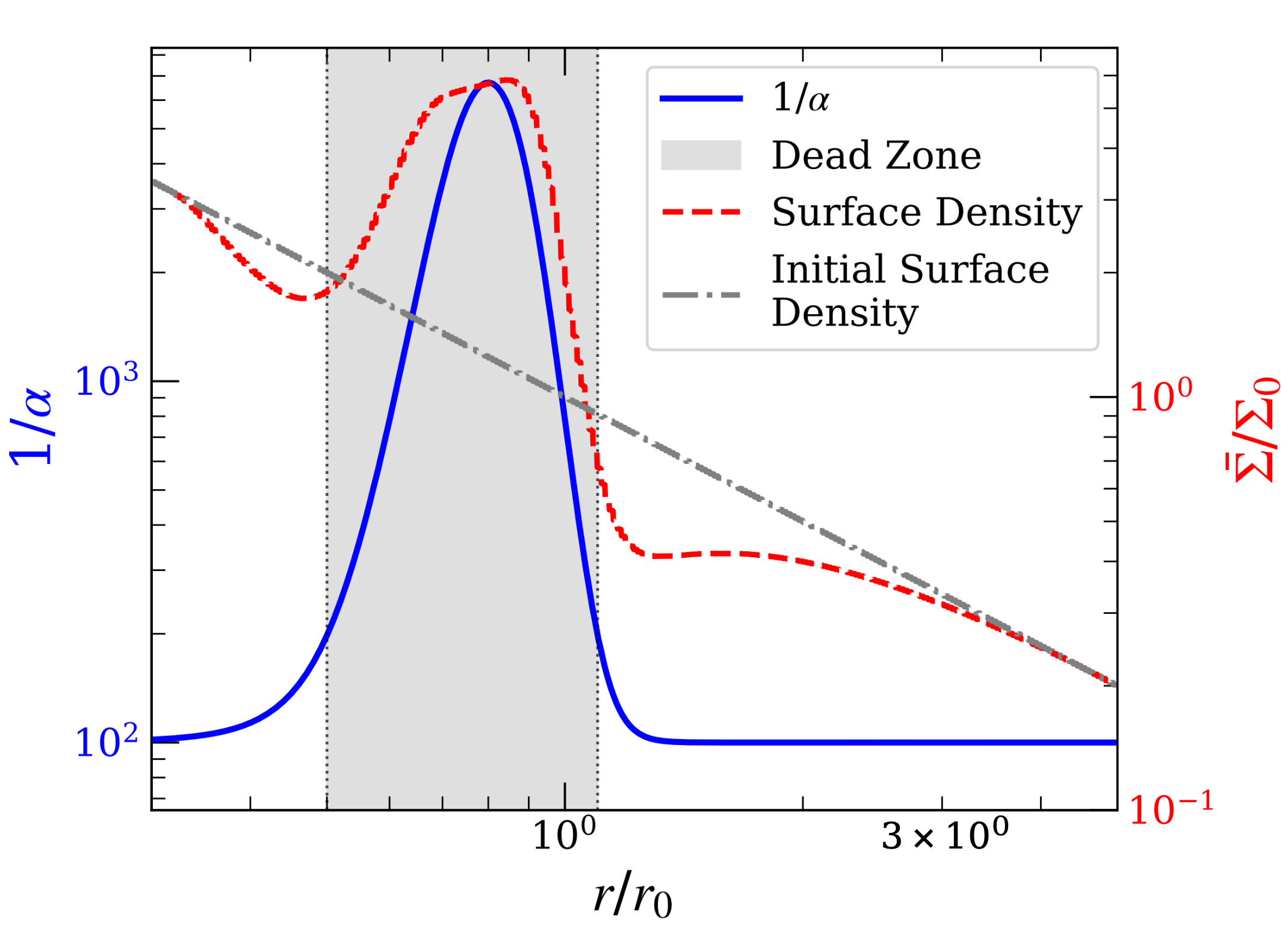

Protoplanetary disks are subject to several instabilities that generate turbulence and contribute to the formation of structures within the disk. Eccentric Cooling Instability arises from variations in cooling rates, leading to the development of eccentric, elongated structures. Regions with lower density cool more efficiently, increasing density and exacerbating the instability. Simultaneously, Vertical Shear Instability develops due to the differential rotation of the disk, where layers move at different speeds, creating Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities and ultimately, turbulence. Both instabilities contribute to the formation of pressure bumps and gaps within the disk, which subsequently influence planet formation and migration by altering the distribution of gas and dust.

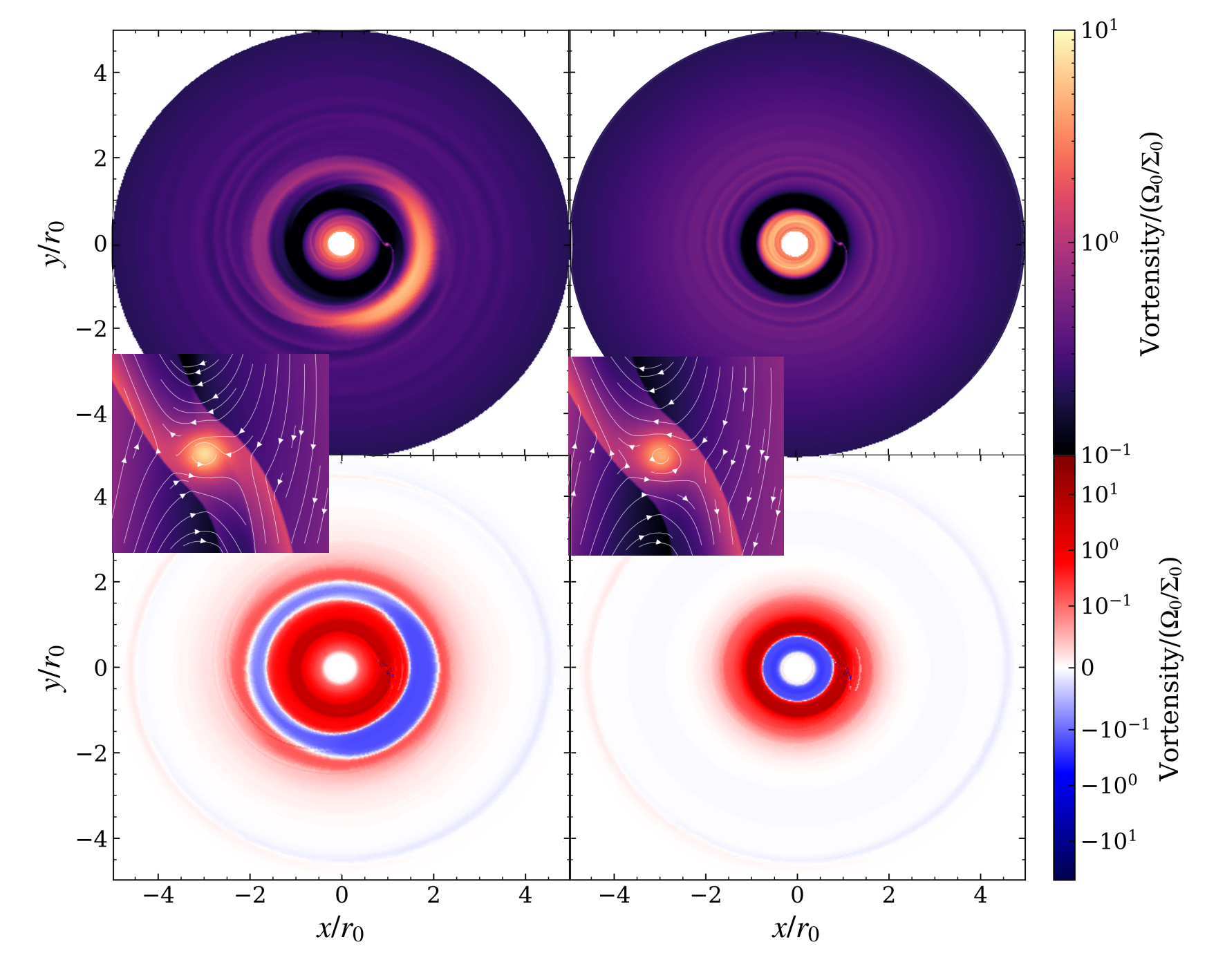

Rossby Wave Instability (RWI) arises in stratified rotating disks due to variations in the shear and vorticity, leading to the formation of large-scale, long-lived vortices. These vortices, typically on the scale of a few disk scale heights, exhibit both prograde and retrograde rotation and are characterized by alternating regions of high and low pressure. Planets undergoing migration, particularly those in the mass range of super-Earths to gas giants, can become dynamically trapped within the potential minima created by these vortices. Alternatively, vortices can act as guides, channeling planetary migration along preferred pathways within the protoplanetary disk. The longevity and strength of these RWI-generated vortices are dependent on the disk’s thermal structure and the degree of stratification, with cooler, more stratified disks supporting more robust vortices.

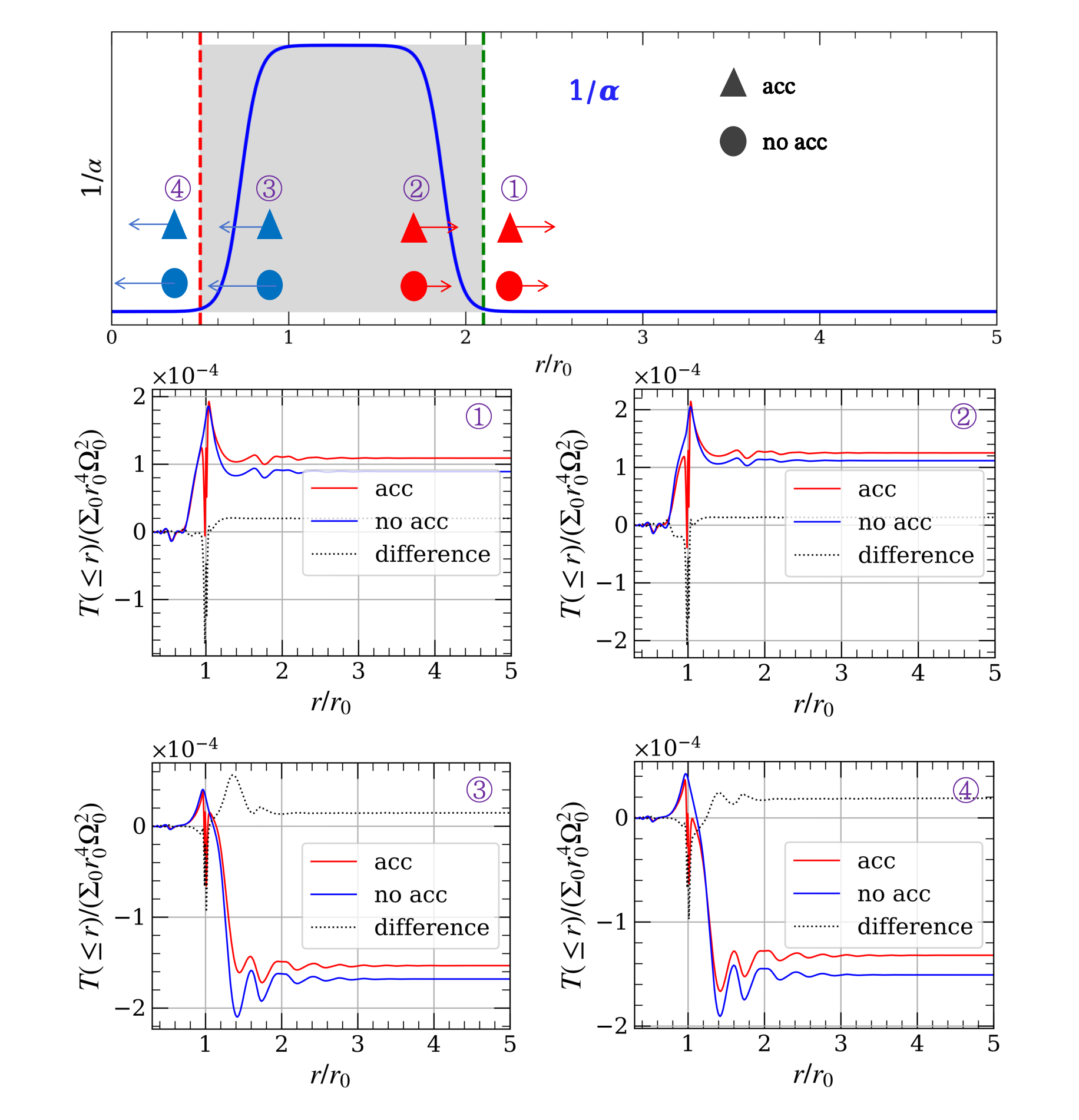

Planetary migration within protoplanetary disks occurs via distinct mechanisms categorized as Type I and Type II. Type I migration applies to lower-mass planets ($< 0.05 M_J$) which do not open a significant gap in the disk. These planets experience gravitational interactions with the disk, leading to a net torque and subsequent inward spiral towards the star. Conversely, Type II migration describes the behavior of more massive planets ($> 0.05 M_J$) capable of opening a gap in the disk. In this scenario, the planet’s orbital evolution is tied to the viscous evolution of the gap itself, often resulting in a slower, but potentially still substantial, migration rate. Both migration types are influenced by the planet’s mass, the disk’s properties (density, viscosity, temperature), and the distance from the star.

Planetary migration within protoplanetary disks is significantly affected by interactions with the disk’s structure, specifically through $Lindblad$ resonances and the potential for $gap$ opening. Simulations indicate a mass-dependent migration pattern when planets encounter gas density bumps; Jupiter-mass planets ($> 0.3 M_J$) tend to migrate outward from these bumps due to the torque generated by the density gradient, effectively repelling them. Conversely, lower-mass planets, such as super-Earths ($< 0.3 M_J$), experience inward migration, converging toward the high-pressure center of the density bump due to a different torque balance. This divergence in migration behavior has significant implications for the final orbital architectures of planetary systems.

Simulating the Swirl: Computational Frontiers

Hydrodynamical simulations are a foundational component of protoplanetary disk research due to the inherent complexity of gas and dust interactions within these environments. These simulations numerically solve the equations of fluid dynamics, including those governing conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, to model the evolution of the disk’s structure and dynamics. Accurately capturing phenomena like angular momentum transport, which drives accretion onto the central star and planet formation, requires resolving a wide range of spatial and temporal scales. Consequently, these simulations are computationally intensive, often requiring high-performance computing resources to model even relatively small regions of a protoplanetary disk over a limited timeframe. They provide critical insights into processes that are difficult or impossible to observe directly, and serve as a primary method for testing theoretical models of planet formation.

Protoplanetary disk simulations commonly employ the $ \alpha $ prescription to model turbulence, a sub-grid scale process requiring parameterization due to computational limitations. This prescription relates the kinematic viscosity, $ \nu $, to the local sound speed, $ c_s $, and disk scale height, $ H$, as $ \nu = \alpha c_s H$. The value of $ \alpha $ is a dimensionless parameter typically ranging from $10^{-2}$ to $10^{-4}$, representing the efficiency of angular momentum transport. These simulations solve the equations of hydrodynamics – conservation of mass, momentum, and energy – using numerical codes like Athena++, which employs a Godunov method to accurately capture shocks and discontinuities present in the disk’s dynamics. Athena++ is a grid-based code capable of utilizing both Cartesian and cylindrical coordinate systems, and is often implemented with adaptive mesh refinement to increase resolution in regions of high gradients.

Current hydrodynamical simulations of protoplanetary disks consistently incorporate the effects of the “dead zone,” a region where magneto-rotational instability (MRI) is suppressed due to low ionization levels, impacting turbulence and angular momentum transport. These simulations also resolve features such as surface density bumps, arising from variations in opacity or external forcing, and gaps created by forming or migrating planets. Analysis of these simulations indicates that the timescale for type III migration of a Jupiter-mass planet – the rate at which it spirals inward due to gravitational interactions with the disk – is approximately 4200 years, although this value is sensitive to disk parameters and planet mass.

Accurate simulation of protoplanetary disk evolution is computationally limited by the wide range of physical scales involved, from the disk size (potentially hundreds of AU) down to the scale height, requiring extremely high resolution to capture vertical structure and turbulence. Explicitly resolving the magneto-rotational instability (MRI), the primary driver of turbulence, demands prohibitively large computational resources, necessitating the use of subgrid models like the $\alpha$ prescription which introduce parameterized approximations. Furthermore, incorporating complex physics like radiative transfer, non-ideal gas effects, and the evolving dust component adds to the computational burden. Even with advancements in algorithms and hardware, simulating disk evolution over timescales relevant to planet formation – potentially millions of years – remains a significant challenge, often requiring supercomputer resources and limiting the ability to explore a wide parameter space.

Worlds Beyond: Echoes of Formation and the Search for Life

The formation of planetary systems is not a static process; instead, it’s a dynamic interplay between disk instabilities, planetary migration, and the ever-present turbulence within the protoplanetary disk. Initial density enhancements – instabilities – can seed the formation of planetesimals, which then accrete into planets. However, these newly formed planets don’t remain stationary; they interact gravitationally with the disk, causing them to migrate inwards or outwards. This migration is further complicated by turbulence, which can both accelerate and decelerate the process, and even trap planets in resonant orbits – configurations where their orbital periods are related by simple ratios. The resulting architecture – the number, mass, and orbital spacing of planets – is therefore a sensitive outcome of these competing forces, explaining the surprisingly diverse range of exoplanetary systems observed and highlighting the complex choreography that ultimately shapes worlds.

Numerical simulations of protoplanetary disks reveal a dynamic interplay of gravitational forces that significantly shapes the arrangement of planets. These studies demonstrate that planets aren’t static entities, but rather bodies susceptible to orbital shifts and rearrangements. Planets can become locked in resonances – predictable gravitational relationships with each other or their host star – stabilizing their orbits for extended periods. Conversely, planets experience inward migration, spiraling closer to the star due to interactions with the surrounding gas disk. However, gravitational encounters between planets can also lead to outward scattering, ejecting some planets from the system entirely or placing them on highly eccentric orbits. These processes collectively explain the observed diversity of exoplanetary systems, including the prevalence of “hot Jupiters” close to their stars and the surprisingly common presence of systems with multiple planets in resonant orbits, suggesting a common origin rooted in these complex disk dynamics.

The remarkable variety of planetary systems observed extends far beyond the familiar arrangement of our own solar system, and unraveling the dynamics of planet formation is paramount to explaining this diversity. Processes like disk instabilities, planetary migration, and turbulence don’t just shape where planets end up, but also determine their ultimate habitability. A planet’s ability to retain an atmosphere, maintain liquid water, and shield against harmful radiation is intrinsically linked to its orbital characteristics and position within a system – factors directly influenced by these formative processes. Consequently, a deeper understanding of these mechanisms isn’t merely an academic pursuit; it’s a critical step in identifying exoplanets that may harbor life, and refining the search for potentially habitable worlds beyond Earth. Simulations, often utilizing reference surface densities like 1700 g/cm$^2$ to estimate migration timescales, are essential tools in this quest, allowing researchers to model complex interactions and predict the likelihood of habitability in diverse planetary scenarios.

Ongoing investigations into planet formation are increasingly focused on incorporating the complex interplay of magnetic fields with fluid dynamics, a field known as Magnetohydrodynamics. Current simulations, while insightful, often simplify the physics of protoplanetary disks; future models aim for greater realism by including these magnetic effects, which can significantly alter disk structure and planet migration. These advanced simulations frequently utilize a reference surface density of 1700 g/cm$^2$ as a benchmark for estimating the timescales over which planets move within the disk. Simultaneously, researchers are striving to enhance the resolution and computational efficiency of these models, allowing for more detailed and accurate predictions of planetary system architectures and ultimately, a better understanding of the conditions that might lead to habitable worlds.

The study of planet migration within protoplanetary disks, particularly concerning the behavior of planets near surface density bumps, reveals the inherent limitations of predictive modeling. As planets interact with these structures – sometimes migrating outward, sometimes becoming trapped – the models demonstrate a sensitivity to initial conditions and subtle variations in disk properties. This aligns with a sentiment expressed by Isaac Newton: “I have not been able to discover the composition of any two bodies.” The research underscores that even with sophisticated hydrodynamical simulations, fully grasping the dynamics of these systems remains a profound challenge, akin to deciphering the fundamental nature of matter itself. The boundaries of predictability, as illustrated by the varying migratory fates of Jupiter-mass planets and super-Earths, highlight the cognitive humility demanded by complex astrophysical phenomena.

Where Do the Paths Lead?

The simulations detailed within demonstrate a patterned response to density variations – large planets pushed outward, smaller ones held fast. Yet, to interpret this as ‘migration’ feels presumptuous. It suggests destinations, implies stability. The disks themselves are not immutable; their structures, born of turbulence and accretion, will shift and dissipate. Any torque calculation, any prediction of planetary placement, is predicated on a snapshot – a fleeting moment before the entire construct succumbs to the inevitable.

The reliance on idealized rims, while necessary for initial inquiry, represents a significant limitation. Real protoplanetary disks are not cleanly sculpted. They are chaotic, messy, and governed by forces not fully captured in even the most sophisticated hydrodynamical models. To truly understand planetary evolution requires acknowledging the inherent unpredictability – the realization that any ‘law’ governing these systems can dissolve at the event horizon of our own understanding.

Future work must address the interplay between these disks and the stars they orbit. Stellar activity, magnetic fields, and the very process of star formation introduce further complexities. Perhaps the most fruitful avenue lies not in refining the simulations, but in accepting their inherent limitations. Discovery isn’t a moment of glory; it’s realizing how little is truly known.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.21328.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Sony Removes Resident Evil Copy Ebola Village Trailer from YouTube

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Can You Visit Casino Sites While Using a VPN?

- The Night Manager season 2 episode 3 first-look clip sees steamy tension between Jonathan Pine and a new love interest

- Holy Hammer Fist, Paramount+’s Updated UFC Archive Is Absolutely Perfect For A Lapsed Fan Like Me

- 10 Essential Marvel Horror Comics (That Aren’t Just Marvel Zombies)

- 40 Inspiring Optimus Prime Quotes

- Gandalf’s Most Quotable Lord of the Rings Line Hits Harder 25 Years Later

- 9 years after it aired, fans discover a Dr Who episode absolutely copy-pasted a Skyrim dragon PNG from a wiki for some background VFX

2025-11-29 05:17