Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis reveals significant challenges in uniquely determining the Berry phase of materials using only quantum oscillation measurements.

Ambiguities arising from the Landé g-factor, Fermi level shifts, and orbital moments necessitate combined experimental approaches for reliable topological state identification.

Determining topological properties of materials relies heavily on extracting the Berry phase from quantum oscillations, yet unambiguous identification remains a persistent challenge. This work, titled ‘Is it possible to determine unambiguously the Berry phase solely from quantum oscillations?’, highlights inherent ambiguities in interpreting these oscillations due to factors like the Landé g-factor, Fermi level shifts, and the complex interplay with the Zeeman effect. We demonstrate that neglecting these influences can lead to questionable conclusions regarding the true Berry phase and, consequently, the topological nature of the material. Can a truly reliable determination of the Berry phase be achieved through quantum oscillations alone, or do we require a more holistic, multi-faceted experimental approach?

The Fermi Surface as a Topological Signature

The Shubnikov-de Haas effect and similar quantum oscillations represent a remarkably direct probe of a material’s electronic structure, specifically its Fermi Surface – the boundary in momentum space separating occupied and unoccupied electron states. These oscillations arise from the quantization of electron orbits in a magnetic field; as the field is varied, the electron orbits cycle through discrete energy levels, leading to periodic changes in measurable quantities like electrical resistance or magnetic susceptibility. By meticulously analyzing the period and amplitude of these oscillations, researchers can reconstruct the shape and size of the Fermi Surface, revealing crucial details about a material’s conductivity, carrier density, and even its topological properties. This technique isn’t limited to simple metals; it proves invaluable in characterizing complex materials like high-temperature superconductors, semimetals, and topological insulators, providing insights inaccessible through other methods and ultimately guiding the development of novel electronic devices.

The precise determination of a material’s electronic properties through quantum oscillations isn’t simply a matter of measuring their frequency; the phase of these oscillations carries crucial information, demanding a sophisticated grasp of quantum mechanics. This phase is profoundly influenced by the Berry phase, a geometric effect arising from the evolution of electron wavefunctions in momentum space, and can be significantly altered by factors like band curvature and the presence of magnetic fields. Correctly interpreting these phase shifts requires accounting for complex phenomena such as quantum interference and the specific symmetry of the material’s band structure – particularly crucial in topological materials where the phase can reveal the existence of protected surface states. Failing to account for these underlying quantum mechanical contributions can lead to misidentification of Fermi surface characteristics and ultimately, an inaccurate understanding of the material’s behavior.

Interpreting quantum oscillations, while revealing crucial information about a material’s electronic structure, demands consideration beyond simply counting charge carriers. The observed frequencies and amplitudes are subtly influenced by factors such as band structure complexities, many-body interactions, and the scattering of electrons within the material. Failing to account for these contributions-including effects like the Dingle temperature which broadens the oscillations-can lead to misinterpretations of key parameters like the Fermi surface area or effective mass. Advanced theoretical models and careful experimental analysis are therefore essential to disentangle these nuances and accurately determine the intrinsic electronic properties, particularly in complex materials where these contributions are most pronounced. This detailed understanding is pivotal for advancing material science and discovering novel quantum phenomena.

The precise interpretation of quantum oscillations extends far beyond simply counting electron orbits; it’s a key that unlocks the hidden potential within newly discovered materials. Subtle variations in oscillation patterns – shifts in frequency or damping of the signal – reveal intricate details about a material’s electronic structure, including the shape of the Fermi surface and the effective mass of charge carriers. These nuances are particularly crucial when investigating materials exhibiting complex behaviors like high-temperature superconductivity or topological phases, where traditional models often fall short. By carefully disentangling these effects, researchers can gain insights into the interplay between electron correlations, band structure topology, and emergent quantum phenomena, ultimately paving the way for the design and development of materials with tailored and enhanced properties.

The Lifshitz-Kosevich Framework: A Semi-Classical Description

The Lifshitz-Kosevich (LK) theory is a semi-classical model used to interpret quantum oscillations observed in materials, such as the de Haas-van Alphen effect and Shubnikov-de Haas effect. It describes these oscillations as arising from the quantization of electron orbits in a periodic potential, specifically in a magnetic field. The theory predicts the temperature and magnetic field dependence of the oscillation amplitude, allowing for the determination of key material properties like the Fermi surface area and effective mass. The LK formalism relates the oscillation period to extremal cross-sectional areas of the Fermi surface, and the amplitude to the density of states at the Fermi level. \frac{1}{T} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} (\frac{d}{dk} S) , where S is the extremal cross-sectional area and k is the wavevector, demonstrates this fundamental relationship, enabling extraction of electronic structure information from experimental data.

Accurate determination of the effective mass m^<i> and the spin factor g^</i> of charge carriers is fundamental to the Lifshitz-Kosevich (LK) theory. The effective mass represents the mass of the carrier as experienced within the crystal lattice, differing from the free electron mass due to band structure effects. The spin factor, g^<i>, accounts for the modification of the Landé g-factor in the solid-state environment and influences the Zeeman splitting of energy levels. Both parameters directly impact the frequency of quantum oscillations, with oscillation frequency F proportional to 1/m^</i> and dependent on g^* through the magnetic field dependence of the relevant energy levels. Precise values for these parameters are therefore essential for correctly interpreting experimental data and extracting information about the material’s band structure and Fermi surface.

The Berry phase, also known as the geometric phase, arises from the adiabatic evolution of the electronic wavefunction in momentum space and directly modifies the oscillation phase observed in quantum oscillation experiments. This phase shift, γ, is not dependent on the usual dynamic phase accumulated due to the carrier’s energy and time, but rather on the solid angle subtended by the Fermi surface’s extremal orbit. The Berry phase can be either 0 or π, depending on the topology of the Fermi surface and the nature of the wavefunction; a non-zero Berry phase leads to a measurable shift in the oscillation period and must be accurately accounted for when determining fundamental material properties from experimental data. Ignoring the Berry phase can result in significant errors in the calculation of the effective mass and carrier density.

Accurate interpretation of quantum oscillation data hinges on correctly relating experimental observations to fundamental material properties. The frequency of observed oscillations is directly proportional to the cyclotron mass m_c, which incorporates the effective mass m^<i> and a spin factor g^</i>. Critically, the phase of the oscillations is sensitive to the Berry phase \phi_B, a geometric property of the electronic band structure. Deviations from expected phase values can indicate non-trivial band topology or the presence of complex scattering mechanisms. Therefore, precise determination of these relationships – frequency to cyclotron mass, and phase to Berry phase – allows researchers to extract parameters such as effective mass, carrier concentration, and Fermi surface topology, ultimately providing insights into the material’s electronic structure and properties.

Beyond the LK Framework: Refinements for Accurate Phase Determination

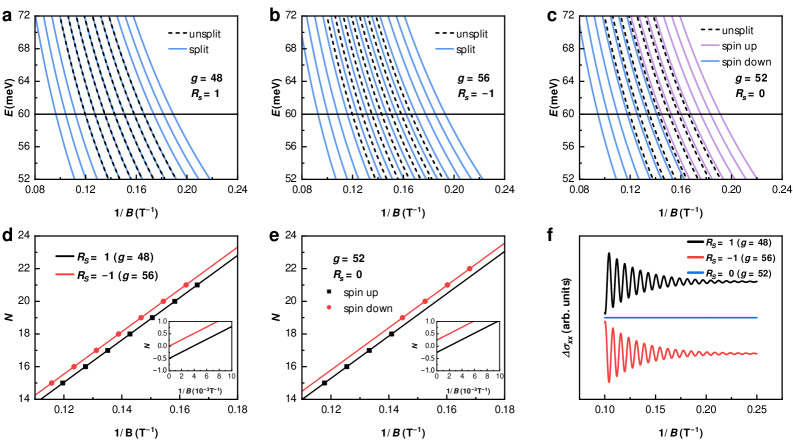

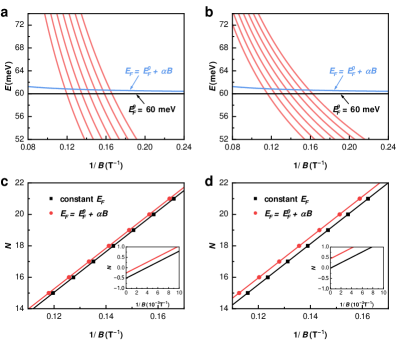

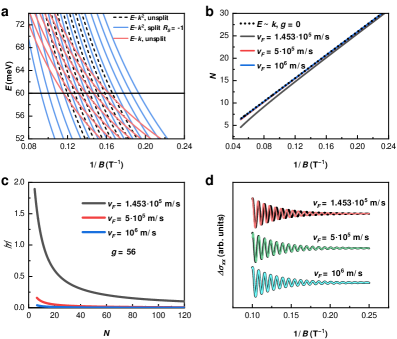

Accurate determination of the quantum oscillation phase necessitates consideration of factors extending beyond the standard Lifshitz-Kosevich (LK) framework. While the LK formula provides a foundational model, deviations arise from complexities in real materials. These include contributions from the Zeeman effect, quantified by the Landé g-factor-which can exceed 100 in certain materials-and geometric effects captured by the Maslov correction, accounting for the shape of orbits in reciprocal space. Additionally, the orbital magnetic moment contributes to the overall phase, and magnetic field-dependent shifts in the Fermi level, with reported coefficients around α = 0.1 \text{ meV/T}, can demonstrably alter the intercept of the Landau level (LL) fan diagram. Neglecting these factors can lead to inaccuracies in the extracted physical parameters from quantum oscillation measurements.

The Zeeman effect, arising from the interaction between electron spin and an applied magnetic field, modifies the energy levels and, consequently, the observed quantum oscillation behavior. This effect is quantified by the Landé g-factor, which represents the ratio of the electron’s spin magnetic moment to its orbital magnetic moment. While typically near 2 for free electrons, the g-factor can deviate significantly in materials due to spin-orbit coupling and other factors, with some compounds exhibiting values as high as 100. A large g-factor directly impacts the energy splitting between spin sub-levels, altering the frequency and amplitude of observed oscillations and necessitating its accurate determination for correct data interpretation. Failure to account for a non-standard g-factor can lead to misidentification of the Fermi surface topology or incorrect estimations of carrier density.

The Maslov correction is a crucial refinement in calculations of quantum oscillation phases, addressing the geometric properties of electron orbits within reciprocal space. This correction arises from the non-commutativity of the canonical variables used to describe these orbits and accounts for the change in area enclosed by an orbit as it traverses the Fermi surface. Without the Maslov correction, calculated phase shifts will deviate from experimental observations, particularly for orbits with complex topologies or those significantly distorted by the magnetic field. The correction is typically expressed as a phase factor of \pm \frac{\pi}{2}, dependent on the orbit’s topology and is applied to ensure accurate determination of key parameters like the Fermi surface area and carrier effective mass from quantum oscillation measurements.

The orbital magnetic moment contributes to the overall quantum oscillation phase, necessitating its inclusion in accurate calculations. This contribution arises from the angular momentum of electrons and its interaction with the applied magnetic field. Critically, the Zeeman effect, resulting from the interaction between electron spin and the magnetic field, can induce a phase shift of π. This induced phase shift can mimic the behavior expected from a non-trivial Berry phase, potentially leading to misinterpretation of the system’s topological properties if not properly accounted for. Therefore, distinguishing between a true Berry phase and a phase shift caused by the Zeeman effect requires careful analysis of experimental data and consideration of the material’s electronic structure.

The magnetic field dependence of the Fermi level introduces a quantifiable shift in the Landau level (LL) fan diagram intercept. Experimental data demonstrates that the Fermi level, E_F, varies linearly with the applied magnetic field, B, described by the coefficient α of 0.1 meV/T. Consequently, E_F(B) = E_F(0) + \alpha B, where E_F(0) is the Fermi level at zero field. Consequently, the intercept of the LL fan diagram, representing the zero-field Fermi energy, will shift proportionally to the magnetic field, requiring accurate accounting for this effect when determining carrier densities and effective masses from oscillation measurements.

Topological Materials: The Berry Phase as a Defining Characteristic

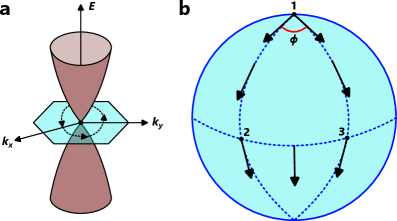

The Berry phase, a geometric effect arising from the quantum mechanical evolution of electrons in momentum space, is fundamental to understanding the unusual electronic behaviors exhibited by topological materials. Unlike conventional materials where electron properties are dictated solely by the energy band structure, topological materials feature band structures with a non-trivial topology – essentially, possessing ‘holes’ or twists that cannot be continuously deformed away. This topology manifests as a phase acquired by the electron wavefunction as it moves around these features in momentum space, the Berry phase. This phase isn’t a dynamical phase linked to energy, but rather a geometric one, impacting properties like electron transport and the emergence of protected surface states. Consequently, the Berry phase dictates the existence of robust edge or surface conduction, even in the presence of defects or disorder, making these materials promising candidates for next-generation electronic devices and quantum computing applications. The strength and characteristics of this phase are directly linked to the topological invariants of the material, providing a powerful tool for characterizing and predicting its behavior.

Characterizing topological materials demands techniques sensitive to the subtle interplay between quantum mechanics and material geometry, and quantum oscillation experiments, when analyzed through the Lifshitz-Kosevich framework, provide precisely that sensitivity. These experiments, typically conducted at extremely low temperatures and high magnetic fields, reveal the quantization of electron orbits within a material. The Lifshitz-Kosevich framework then allows researchers to extract crucial information from the oscillation frequencies and, importantly, the phase of these oscillations. Deviations from expected phase behavior can signal the presence of a non-trivial Berry phase – a geometric phase acquired by electrons due to their movement in momentum space – and thus, evidence of the material’s topological nature. This approach isn’t merely a confirmation; it quantitatively maps the Fermi surface and provides insights into the material’s band structure, offering a powerful tool for both discovery and detailed analysis of these exotic states of matter.

The subtle shifts observed in quantum oscillation phase provide a powerful diagnostic for identifying materials with non-trivial topological properties. Quantum oscillations, arising from the cyclical behavior of electron orbits in magnetic fields, normally exhibit a predictable phase relationship. However, in topological materials, the Berry phase – a geometric phase acquired by the electron wavefunction due to the band structure’s topology – introduces an additional phase shift to these oscillations. This shift, detectable through precise measurements and analysis using the Lifshitz-Kosevich framework, directly reflects the underlying topological invariants of the material. Consequently, deviations from the expected oscillation phase serve as a fingerprint, confirming the presence of topologically protected states and offering insights into the material’s unique electronic behavior – a particularly crucial technique in characterizing novel materials like Weyl semimetals where the Berry phase governs unusual transport phenomena and chiral anomalies.

Weyl semimetals, a cutting-edge class of materials, exhibit remarkable transport properties directly governed by the Berry phase – a geometric phase acquired by electrons as they move through momentum space. Unlike conventional materials, these semimetals feature linearly dispersing bands that touch at specific points, known as Weyl nodes, creating unique chiral anomalies. The Berry phase around these nodes isn’t merely a theoretical curiosity; it fundamentally alters how electrons behave, leading to phenomena like the chiral anomaly, which manifests as an unusual negative magnetoresistance. This effect arises because the Berry phase allows electrons to bypass conventional scattering mechanisms, enabling highly efficient and dissipationless transport. Consequently, the analysis of transport measurements in Weyl semimetals provides a direct probe of the underlying Berry curvature and confirms the non-trivial topology that defines these materials, paving the way for novel electronic devices with enhanced performance and functionality.

The pursuit of definitively isolating the Berry phase through quantum oscillations, as detailed in the study, resembles a deceptively simple equation with hidden variables. The complexities introduced by the Landé gg-factor, Fermi level shifts, and orbital moments demonstrate that observed phenomena aren’t always what they seem. As Albert Einstein once stated, “The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is comprehensible.” This holds true here; while the underlying physics is understandable, extracting a singular, unambiguous value for the Berry phase requires meticulous consideration of all contributing factors. If it feels like magic – a clear signal amidst noisy oscillations – one hasn’t fully revealed the invariant, or accounted for the complete set of physical parameters influencing the measurement. A truly elegant solution demands a provable methodology, not merely empirical observation.

Beyond Oscillations: The Path Forward

The pursuit of unambiguous topological state identification, as illuminated by this work, reveals a persistent truth: experimental physics, despite its empirical foundation, is rarely a matter of simple deduction. To believe a Berry phase can be uniquely extracted from quantum oscillations alone is to succumb to a convenient, yet ultimately flawed, simplification. The inherent degeneracy between the Berry phase and the Landé gg-factor, coupled with the sensitivity to Fermi level positioning and the often-neglected contributions of orbital moments, demands a more nuanced approach.

Future progress hinges not on increasingly precise oscillation measurements – though refinement is always desirable – but on complementary techniques. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, for example, offers a direct probe of band structure and Berry curvature, providing a critical validation of phases inferred from transport measurements. Likewise, theoretical advancements must move beyond perturbative calculations and embrace methods capable of accurately accounting for strong correlations and complex band topologies. A proof of correctness, not merely consistency with Lifshitz-Kosevich theory, should be the guiding principle.

The field would be well-served by acknowledging that identifying a topological state is not merely about observing a specific oscillation pattern, but about rigorously demonstrating the non-trivial topology of the electronic band structure. To settle for less is to mistake correlation for causation, and to risk building castles upon the shifting sands of experimental uncertainty.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09560.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Sony Removes Resident Evil Copy Ebola Village Trailer from YouTube

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- The Night Manager season 2 episode 3 first-look clip sees steamy tension between Jonathan Pine and a new love interest

- So Long, Anthem: EA’s Biggest Flop Says Goodbye

- OBEX Review: A Retro-Tech Fairy Tale With a Horror Edge

- Netflix’s New Mystery Thriller Series Is Officially a Hit With Almost 80 Million Hours Viewed

- Haley Kalil Seeks “Good Guys” Amid Matt Kalil Lawsuit

- 3 Years Ago Today, the Best Action Anime Series Took a 360-Degree Turn (and Became Even Better)

- 10 Fantasy Movies That Are 10/10 From Start To Finish

2026-01-16 01:29