Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that light can induce magnetism in materials through subtle geometric properties of their electronic structure.

This review demonstrates that light-induced magnetization arises from quantum geometric effects, unifying the inverse Faraday and inverse Cotton-Mouton effects through the quantum metric and Berry curvature.

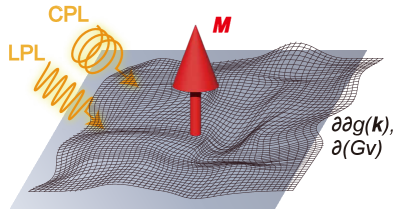

Conventional magneto-optical effects rely on established principles, yet a comprehensive understanding of light-induced magnetization originating from purely geometric properties of materials has remained elusive. In ‘Light-induced Magnetization by Quantum Geometry’, we demonstrate a mechanism for both the inverse Faraday and inverse Cotton-Mouton effects arising from the quantum metric quadrupole and weighted quantum metric within electronic systems. Utilizing semiclassical Boltzmann transport theory, we establish a general formalism revealing how light’s electric field induces magnetization through these quantum-geometric tensors. Could exploiting these effects pave the way for novel optical control of magnetism and the design of materials with tailored magneto-optical responses?

Unveiling the Hidden Geometry of Electron Behavior

For decades, the field of condensed matter physics has explained how electrons move through materials using the concept of Berry curvature – a geometric property of quantum states that effectively acts as a magnetic field in momentum space. However, this framework proves insufficient when describing the full complexity of light-matter interactions, particularly in novel materials. Traditional models, reliant solely on Berry curvature to understand transport phenomena, often fail to predict observed behaviors, leaving gaps in understanding how electrons respond to external stimuli and internal material properties. This limitation stems from a crucial oversight: the neglect of the Quantum Metric, a complementary geometric property that dictates the infinitesimal distance between quantum states and profoundly influences the velocity of electrons. A complete picture necessitates acknowledging both geometric contributions, revealing a more nuanced and accurate description of electron dynamics beyond what conventional approaches provide.

The behavior of electrons in materials isn’t solely dictated by their particle-like properties; increasingly, research demonstrates the profound influence of the geometric characteristics of their quantum states – a field known as Quantum Geometry. This framework moves beyond traditional understandings of electron transport, revealing that the very shape of a quantum state in momentum space can dictate how electrons move and interact. Unlike Berry curvature, which focuses on changes in quantum states, Quantum Geometry considers the intrinsic geometric properties – like distances and angles – within that space. These properties, captured mathematically by the g_{ij} tensor – the Quantum Metric – determine how quickly and efficiently electrons propagate, influencing crucial material properties like conductivity and even the emergence of novel electronic phases. By probing these hidden geometric mechanisms, scientists are uncovering previously inaccessible avenues for designing materials with tailored and enhanced functionalities.

The behavior of electrons within materials isn’t solely dictated by established principles like Berry curvature; a complete understanding requires considering the Quantum Metric, a complementary geometric property of quantum states. While Berry curvature describes how wave functions change in response to external forces, the Quantum Metric quantifies the intrinsic distance between infinitesimally separated quantum states, essentially defining how easily an electron can move within the material’s quantum landscape. Recent research demonstrates that both quantities contribute significantly to electronic transport, with the Quantum Metric influencing electron velocities and effectively modifying the material’s response to applied electric fields. Ignoring the Quantum Metric leads to an incomplete picture, particularly in systems with strong electron interactions or complex band structures, as it governs aspects of conductivity beyond what traditional models predict and opens possibilities for engineering materials with tailored electronic properties. This synergistic interplay between Berry curvature and the Quantum Metric provides a more holistic framework for predicting and manipulating electron behavior, ultimately paving the way for advancements in areas like high-efficiency solar cells and novel electronic devices.

Light-Induced Magnetization: A Geometric Origin Revealed

The Inverse Faraday Effect (IFE) and Inverse Cotton-Mouton Effect (ICME) are phenomena where linearly polarized light induces magnetization in initially non-magnetic materials. The IFE manifests in materials lacking magnetic symmetry, generating a static magnetization proportional to the square of the electric field of the incident light and the inverse of the photon energy. Similarly, the ICME induces magnetization in materials possessing inversion symmetry, with the induced magnetization being proportional to the square of the light’s electric field. These effects are distinct from the Faraday and Cotton-Mouton effects, which describe the rotation of polarization in magnetic materials, and are observed even in the absence of an external magnetic field, indicating a direct optical induction of magnetic order.

Conventional explanations of the Inverse Faraday and Inverse Cotton-Mouton Effects, which describe light-induced magnetization, fail to fully account for observed magnitudes and directional dependencies. These phenomena are now understood to originate from the material’s Quantum Geometry, specifically the geometric properties of its electronic band structure. Unlike traditional mechanisms reliant on spin or charge dynamics, these effects are directly proportional to the \text{Weighted Quantum Metric} and \text{Quantum Metric Quadrupole} , tensors that characterize the internal geometry of the material’s wavefunctions. This geometric origin provides a framework for predicting and interpreting light-induced magnetization in materials where conventional mechanisms are insufficient, and it necessitates consideration of band structure topology beyond simple band gap analysis.

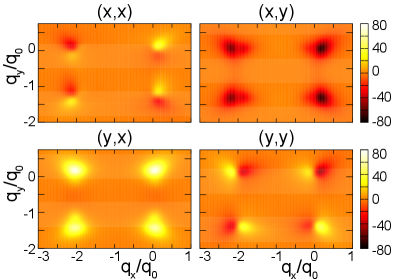

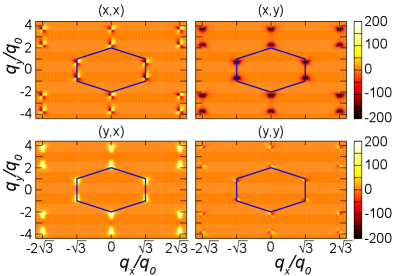

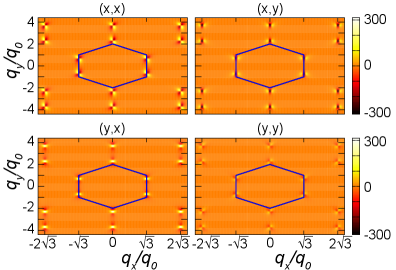

Light-induced magnetization, as described by the Inverse Faraday and Cotton-Mouton effects, arises from contributions of the Weighted Quantum Metric and Quantum Metric Quadrupole tensors. The Weighted Quantum Metric, a rank-2 tensor, describes the geometric properties of the electronic band structure and its response to external fields. The Quantum Metric Quadrupole, a rank-4 tensor, characterizes the anisotropy of this geometric response. Calculations demonstrate that these tensors couple directly to the applied light field, generating a macroscopic magnetization M. Observable effects are predicted to be maximized under symmetry conditions where specific components of these tensors are non-zero, allowing for experimental verification of this geometric origin of magnetization.

Modeling Magnetization Currents: A Geometric Perspective

The Magnetization Current, describing the directional flow of magnetic moments within a material, is computationally derived using both the Boltzmann Transport Equation and Semiclassical Equations of Motion. The Boltzmann Transport Equation, a kinetic equation, models the statistical behavior of these moments, while Semiclassical Equations of Motion provide a deterministic trajectory for each moment under applied forces. Combining these approaches allows for the calculation of current density \mathbf{J}_m as a function of material properties, external fields, and temperature. This methodology facilitates the prediction of magnetization current magnitudes and directional dependencies, enabling analysis beyond traditional charge current calculations and accounting for spin-dependent transport phenomena.

Calculations based on the Boltzmann Transport Equation and Semiclassical Equations of Motion demonstrate that the Magnetization Current is directly influenced by the Weighted Quantum Metric and Quantum Metric Quadrupole when an Electric Field is applied. Specifically, these calculations predict a current magnitude of 10-14 A for Circularly Polarized Light (CPL) and 10-13 A for Linearly Polarized Light (LPL). The contribution of the Weighted Quantum Metric and Quantum Metric Quadrupole allows for quantitative prediction of the magnetization current generated by incident electromagnetic radiation, providing a basis for understanding and optimizing material response.

This modeling framework extends beyond conventional transport theory by incorporating the Weighted Quantum Metric and Quantum Metric Quadrupole, enabling the prediction of magnetization currents even in scenarios where traditional approaches fail to accurately describe material behavior. This capability is achieved through a semi-classical treatment of electron dynamics, allowing for the quantification of deviations from established models like the Drude or Boltzmann transport equations. Consequently, the framework facilitates a predictive approach to material design, enabling researchers to estimate magnetization currents – on the order of 10^{-{14}} A (CPL) and 10^{-{13}} A (LPL) – in novel materials before synthesis and experimental validation, thereby accelerating the discovery of materials with tailored magnetic properties.

Spintronics and the Future of Material Design

The burgeoning field of spintronics – which exploits the spin of electrons rather than just their charge – stands to be revolutionized by a deeper understanding of how material structure dictates light-induced magnetization. Current research demonstrates that illuminating certain materials with light can generate a flow of spin, potentially enabling faster, more energy-efficient data storage and processing. This effect isn’t merely a surface phenomenon; it’s intrinsically linked to the arrangement of atoms within the material itself. Precisely tailoring this atomic architecture – creating specific symmetries or introducing controlled defects – allows for the manipulation of light-matter interactions, ultimately maximizing the generated spin current. Consequently, materials science is now focused on designing novel compounds and heterostructures that exhibit enhanced light-induced magnetization, paving the way for compact and powerful spintronic devices with applications ranging from magnetic sensors to quantum computing components.

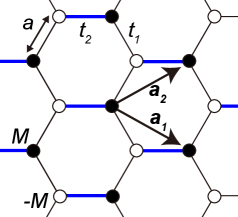

Computational material science leverages the Tight-Binding Model to explore light-induced magnetization in materials possessing hexagonal lattice structures. This approach, rooted in quantum mechanics, allows researchers to approximate the electronic structure and predict how photons interact with the material’s atomic orbitals. By calculating the resulting electron dynamics, the model reveals pathways for generating and controlling magnetization currents, effectively simulating the material’s response to light. The power of this technique lies in its ability to systematically investigate the influence of material composition and structural modifications – such as introducing defects or strain – on the observed effects, thereby providing a crucial link between material design and spintronic device performance. Through these simulations, scientists can optimize materials for enhanced light-matter interactions and ultimately tailor properties for novel applications in data storage and processing, without the need for extensive and costly experimental trials.

The capacity to manipulate magnetization through light offers exciting possibilities for next-generation spintronic devices, and research indicates that subtle alterations to a material’s symmetry play a crucial role in controlling this effect. Specifically, deviations from perfect rotational symmetry within the material’s structure can dramatically amplify or diminish the generated magnetization current. This sensitivity arises because symmetry dictates how light interacts with the material’s electronic bands, influencing the spin polarization of photoexcited carriers. Consequently, by intentionally introducing asymmetry – through strain, defects, or specific material arrangements – researchers gain a powerful lever for fine-tuning device performance. This control parameter allows for the design of materials optimized for enhanced magnetization currents, leading to more efficient and responsive spintronic components, or conversely, for suppressing unwanted effects and improving stability.

The study elucidates a harmony between seemingly disparate phenomena – the inverse Faraday and inverse Cotton-Mouton effects – revealing them as manifestations of a deeper, unified principle rooted in quantum geometry. This echoes Friedrich Nietzsche’s observation, “There are no facts, only interpretations.” The research doesn’t simply present facts about light-induced magnetization; it interprets the underlying mechanisms through the lens of quantum metric quadrupoles and weighted quantum metrics. The elegance of this approach lies in its ability to distill complex interactions into a coherent framework, demonstrating how beauty scales when foundational principles are understood, while clutter – or unresolved complexities – does not.

Beyond the Glow: Charting Future Directions

The demonstration that light-induced magnetization stems from the subtle interplay of quantum geometry – the metric quadrupole and weighted curvature – feels less like a resolution and more like an elegant rephrasing of the question. It clarifies how light sculpts magnetism, but the ‘why’ remains, shrouded in the complexities of materials discovery. The current formalism, while internally consistent, relies heavily on Boltzmann transport; a natural progression demands exploration of alternative kinetic equations, perhaps those incorporating non-equilibrium Green’s functions, to capture transient dynamics with greater fidelity.

A lingering challenge resides in the separation of quantum-geometric contributions from more conventional magnetoptic effects. To truly isolate the influence of Berry curvature, investigations must move beyond simple models and confront the messy reality of strongly correlated materials. One anticipates that materials with maximized quantum-geometric signatures – topological semimetals and Weyl semimetals being obvious starting points – will offer the clearest experimental validation, yet the quest for such materials remains an exercise in serendipity.

Ultimately, the value of this work isn’t merely in explaining existing phenomena, but in suggesting a new design principle. If magnetization can be reliably controlled via geometric tailoring, one envisions novel spintronic devices where information is encoded not in magnetic moments themselves, but in the very fabric of the material’s band structure. It’s a quiet revolution, perhaps, but revolutions rarely shout.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09637.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Sony Removes Resident Evil Copy Ebola Village Trailer from YouTube

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Daredevil Is Entering a New Era With a Chilling New Villain (And We Have A First Look) (Exclusive)

- The Night Manager season 2 episode 3 first-look clip sees steamy tension between Jonathan Pine and a new love interest

- So Long, Anthem: EA’s Biggest Flop Says Goodbye

- Tom Hardy’s Action Sci-Fi Thriller That Ended a Franchise Quietly Becomes a Streaming Sensation

- James Bond: 007 First Light is “like a hand fitting into a glove” after making Hitman, explains developer

- Robert Irwin Looks So Different With a Mustache in New Transformation

- A new National Lampoon film?

2026-01-16 03:08