Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new theoretical framework explores the unusual singularities that emerge in the parameter spaces of complex systems undergoing phase transitions, revealing hidden connections between symmetry and topology.

This review details the properties of diabolical critical points – a specific class of phase diagram topological defects – and their implications for understanding emergent phenomena in quantum many-body systems.

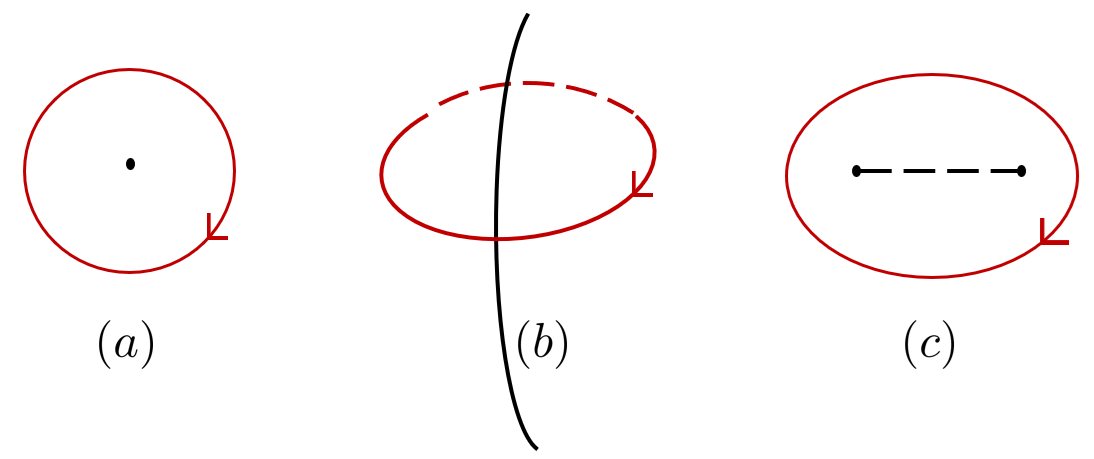

While phase transitions are well-understood as topological defects in the parameter spaces of physical systems, their higher-dimensional analogs remain largely unexplored. This paper, ‘In search of diabolical critical points’, investigates these higher-codimension defects, revealing a novel type of singularity-the ‘diabolical critical point’-characterized by non-trivial winding of equilibrium states rather than abrupt changes in matter. We demonstrate that these points can be stable even in classical systems and propose conditions for their existence, illustrating their potential in (1+1)-dimensional quantum models. Could a deeper understanding of diabolical critical points reveal new organizing principles for complex many-body systems and emergent symmetries?

Unveiling Order Through Geometric Imperfections

Conventional phase diagrams, the workhorses of condensed matter physics, rely on identifying and tracking order parameters – quantities that characterize the system’s state, like magnetization or crystal orientation. However, these diagrams often fall short when describing materials exhibiting complex behaviors driven by topological defects. These defects, such as vortices, domain walls, or dislocations, are stable, localized disturbances in the material’s order and aren’t easily captured by global order parameters. The presence of these defects can dramatically alter a material’s properties, leading to unexpected phenomena like quantized conductance or novel magnetic states. Consequently, a complete understanding of many modern materials-particularly those exhibiting unconventional superconductivity or complex magnetism-requires moving beyond traditional phase diagrams and explicitly incorporating the role of these topologically protected imperfections.

The emergence of non-conventional phases of matter often hinges on the behavior of topological defects, most notably vortices, within a material. These aren’t simply imperfections, but stable, localized disturbances in the order of the system-think of swirling eddies in a fluid. Unlike traditional phase transitions described by global order parameters, transitions mediated by these defects involve changes in their density or arrangement, leading to entirely new states of matter. For instance, in superconductors, vortices allow magnetic fields to penetrate the material, dramatically altering its properties. Similarly, in liquid crystals and other soft matter systems, defects dictate the overall texture and response to external stimuli. Consequently, a thorough understanding of vortex dynamics and their interactions is paramount for predicting and characterizing these complex phases and the transitions between them, extending beyond the limitations of conventional phase diagrams and offering insights into novel material behavior.

Even seemingly simple, well-characterized classical systems can display unexpectedly intricate behaviors when topological features emerge. These aren’t exotic, quantum mechanical effects, but rather consequences of the system’s geometry and the constraints imposed upon it. Consider, for instance, the arrangement of defects in liquid crystals or the formation of disclinations in elastic materials; these topological imperfections fundamentally alter the system’s properties. A key characteristic is their inherent stability – unlike fleeting fluctuations, topological defects are protected from continuous deformation and require significant energy to eliminate. This robustness leads to novel phases of matter and unusual transitions, defying predictions based solely on traditional order parameters. The presence of such features fundamentally reshapes the system’s response to external stimuli, creating complex, emergent phenomena even in materials governed by classical physics.

Topology as the Blueprint for Phase Transitions

The Kosterlitz-Thouless (KT) transition is a continuous phase transition occurring in two-dimensional systems, notably in thin films and superfluids, and is uniquely characterized as being driven by the proliferation of topological defects – vortex-antivortex pairs. Unlike conventional phase transitions involving an order parameter, the KT transition features no such parameter; instead, the system transitions from an ordered phase with bound vortex-antivortex pairs to a disordered phase where these pairs unbind and move freely. This unbinding is accompanied by a change in the correlation function from exponential decay in the ordered phase to a power-law decay in the disordered phase, indicating a qualitative shift in the system’s behavior. The transition temperature, T_c, is determined by the density and interaction strength of these topological defects, demonstrating that topological features can fundamentally dictate the macroscopic properties of a system.

Unlike conventional phase transitions characterized by changes in an order parameter – a quantity that measures the degree of order within a system – Kosterlitz-Thouless transitions and similar phenomena are defined by alterations in the concentration and interactions of topological defects. These defects, such as vortices in two-dimensional systems, do not simply disappear or condense; instead, the transition is marked by a qualitative shift in their behavior, often involving a change in their pairing or unbinding. The density of these defects, and how they collectively influence the system’s long-range order, dictates the phase, rather than an explicit order parameter value. This means the system’s properties change not because of an alteration in a measurable order, but due to a shift in the arrangement and dynamics of these inherent imperfections.

Phase boundaries in systems undergoing topological transitions are directly determined by the dynamics and concentration of topological defects. These defects, such as vortices or domain walls, impede long-range order and contribute to the system’s overall energy. As external parameters are tuned, the density of these defects changes, and a critical density is reached where the system undergoes a qualitative shift in its properties. Below a certain critical temperature or above a critical field, defects may be suppressed, leading to an ordered phase; conversely, increasing temperature or reducing the field can proliferate defects, resulting in a disordered phase. The precise location of the phase boundary is thus dictated by the behavior of these defects – their creation, annihilation, and interactions – and represents a transition between regimes of differing defect densities and associated physical characteristics.

Mathematical Landscapes: Describing Topological Order

Fiber bundles mathematically describe spaces where topological properties define the relevant characteristics, rather than geometric coordinates. A fiber bundle consists of a base space, a total space, and a projection function mapping points in the total space to points in the base space. The fibers, which are the preimages of points in the base space, represent the degrees of freedom associated with that point, and are often manifolds themselves. This formalism allows for the systematic organization of these degrees of freedom by relating local properties of the fiber to the global topology of the base space; for example, a non-trivial topology in the base space can lead to constraints on the allowed configurations of the degrees of freedom represented by the fiber. B \rightarrow E \rightarrow F represents a fiber bundle, where B is the base space, E is the total space, and F is the fiber.

Topological order in condensed matter systems is characterized by the presence of defects-such as vortices or domain walls-whose behavior is governed by the underlying topology of the space they inhabit. These spaces are mathematically described using concepts like the circle (S^1), the sphere (S^2), and the three-dimensional sphere (S^3). The dimensionality of these spaces dictates the types of defects that can exist and how they interact. For instance, a S^1 space supports vortex lines, while S^2 can host point defects known as monopoles. The topological properties of these spaces ensure that defects are stable and cannot be removed without changing the overall topology of the system, leading to robust, non-local order.

The special orthogonal group SO(2) represents the group of rotations in two dimensions, and is crucial for characterizing the symmetries present in topological order. Specifically, SO(2) is isomorphic to the circle group U(1), and its elements can be parameterized by a single angle θ. This group dictates the allowed transformations of the topological degrees of freedom without changing the underlying physics; defects within the system are constrained to transform according to the representations of SO(2). Consequently, the symmetry group SO(2) defines the possible types of defects and their allowed configurations, influencing the system’s overall behavior and response to external perturbations. The constraints imposed by SO(2) ensure the stability and consistency of the topological phase.

Unveiling the Family of Ground States: A New Symmetry

A systematic understanding of a physical system’s ground states often begins with organizing them – not by energy, but by their qualitative differences, a process formalized through the concept of a topological family. This approach maps each distinct ground state onto a point within a topological space, where the ‘closeness’ of points reflects the similarity of the corresponding states. Crucially, this geometric representation isn’t arbitrary; the topology of the space dictates how states evolve and connect as external parameters change. By leveraging the tools of topology, researchers can identify and classify different phases of matter, predict the emergence of novel phenomena, and gain insights into the underlying principles governing complex systems – transforming a potentially intractable many-body problem into a manageable geometrical one. This framework allows for the identification of critical points and phase transitions not readily apparent through traditional methods, revealing a deeper connection between symmetry, order, and the fundamental properties of matter.

The Ising Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking (SSB) family provides a concrete illustration of how a system’s ground state topology directly reflects the breaking of a symmetry. In this framework, the ground states are not simply minimized energy configurations, but are organized into a topological space where different states correspond to distinct points within that space. The symmetry breaking isn’t an abrupt change, but rather a continuous deformation of the ground state manifold as external parameters are altered. This manifests as the emergence of multiple, degenerate ground states, each representing a different ‘choice’ in breaking the initial symmetry – akin to a ball rolling off a hilltop and settling into one of several equivalent valleys. Crucially, the connectivity and structure of this topological space – the arrangement of these valleys – reveal the nature of the symmetry breaking and dictate the system’s low-energy behavior, demonstrating a profound link between topology and physical observables.

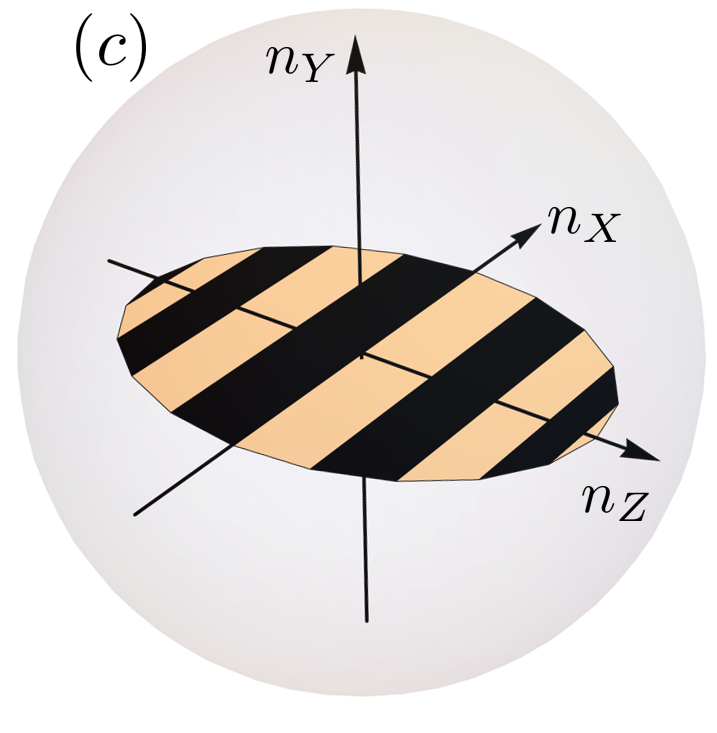

Diabolical critical points (DCPs), points of qualitative change in a system’s behavior, aren’t simply accidental occurrences; their existence is fundamentally linked to the organization of a system’s ground states into topological families. This work demonstrates that the emergence of a DCP necessitates the presence of N relevant operators – perturbations that drive the system away from the critical point – all sharing the same scaling dimension. This stringent requirement suggests a deep connection between the system’s symmetries, its allowed perturbations, and the underlying topology governing its ground states. The presence of these identically-scaled operators effectively ‘stacks’ the critical behavior, leading to the unique characteristics observed at DCPs and revealing a powerful constraint on systems exhibiting complex, topologically-ordered phases.

The organization of ground states into topological families gives rise to an emergent symmetry, denoted as Ĝ, which significantly expands upon the microscopic symmetry G of the system. This emergent symmetry isn’t merely an extension, but is specifically transitive on the space S_{N-1}, meaning it can map any point within this space to any other. The existence of this transitive property indicates a fundamental reorganization of the system’s symmetries as it transitions between different ground states, effectively creating new, collective behaviors not present in the original microscopic description. This expanded symmetry is crucial for understanding the system’s response to perturbations and dictates the allowed collective excitations, providing a powerful framework for analyzing complex phenomena arising from topological order.

Compact Boson Conformal Field Theories (CFTs) represent a sophisticated analytical framework for dissecting physical systems characterized by topological order and the emergence of novel phenomena. These theories, constructed upon the foundations of topological families and symmetry breaking, move beyond traditional approaches by focusing on the collective behavior of excitations and the global properties of the system’s ground states. By leveraging the mathematical rigor of CFTs, researchers can effectively describe systems where long-range entanglement and fractionalized excitations are prevalent, offering insights into materials exhibiting exotic quantum phases. The power of this approach lies in its ability to classify and predict the behavior of these systems, even when traditional perturbative methods fail, paving the way for a deeper understanding of complex quantum matter and potentially enabling the design of materials with tailored topological properties.

Beyond Conventional Paradigms: A New Frontier in Condensed Matter

The design of materials with unprecedented functionalities increasingly relies on harnessing the intricate relationship between a material’s topology, how its symmetry is broken, and the resulting emergent phenomena. Topology, concerned with properties preserved under continuous deformations, dictates the existence of protected states robust against imperfections, while symmetry breaking introduces order parameters that can be tuned to control material behavior. When these two concepts intertwine, entirely new phases of matter can emerge – exhibiting properties not found in traditional materials. For example, manipulating topological defects within a material-points or lines where order is disrupted-can create pathways for electrons with extraordinary transport characteristics. This interplay allows researchers to move beyond simply discovering materials and towards designing materials with specific, tailored properties, potentially revolutionizing fields from superconductivity and spintronics to energy storage and quantum computing.

Recent investigations reveal a compelling link between Berry Curvature – a geometric property of quantum states arising from the wavefunction’s phase – and the formation of topological defects within materials. These defects, akin to dislocations in crystals but existing in the space of quantum states, profoundly influence electron behavior and can be harnessed for novel device functionalities. Researchers are discovering that manipulating Berry Curvature – through external fields or material design – allows for precise control over the location and properties of these defects, effectively creating pathways for electrons with exceptionally low resistance or enhanced spin polarization. This approach promises a new paradigm for creating robust electronic devices, less susceptible to scattering and disorder, and opens exciting possibilities for realizing topologically protected quantum bits – the building blocks of future quantum computers – where information is encoded in the very geometry of the material, offering inherent resilience against environmental noise.

The principles guiding research into topological materials are increasingly recognized as foundational across seemingly disparate scientific disciplines. Concepts initially developed to describe the robust electronic states in condensed matter systems-rooted in the mathematical properties of topology-are now proving invaluable in cosmology, where the large-scale structure of the universe and the nature of cosmic defects are being re-examined through a topological lens. Similarly, in high-energy physics, topological ideas are informing models of fundamental particles and forces, particularly in understanding the stability of certain exotic states and the behavior of gauge fields. This interdisciplinary resonance suggests that topology isn’t merely a mathematical curiosity, but a fundamental organizing principle governing physical systems across scales, potentially unifying diverse areas of research under a common theoretical framework and inspiring novel approaches to longstanding problems.

The exploration of phase diagrams, as detailed in the article, necessitates a keen eye for identifying singularities and emergent behaviors. This process echoes the spirit of scientific inquiry, where observation and logical deduction are paramount. As Galileo Galilei famously stated, “You cannot teach a man anything; you can only help him discover it himself.” The study of diabolical critical points, arising from the spontaneous symmetry breaking discussed in the article, isn’t about imposing understanding, but rather meticulously mapping the patterns within the system – allowing the inherent structure to reveal itself through careful experimentation and theoretical development. The framework proposed seeks to illuminate these critical points, fostering discovery rather than dictating conclusions.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The pursuit of diabolical critical points, as outlined in this work, reveals less a destination and more a cartography of ignorance. Each identified singularity in a phase diagram isn’t a solution, but rather a higher-resolution map of the questions that remain. The framework connecting these points to emergent symmetries and topological defects, while promising, readily exposes its limitations – specifically, the inherent difficulty in extending these theoretical tools to genuinely disordered systems. The very notion of a ‘critical point’ feels precarious when confronted with landscapes devoid of underlying order.

Future investigations will undoubtedly require a deeper engagement with the mathematical formalisms of fiber bundles, not simply as an abstract tool, but as a means of predicting observable consequences. The true test lies in identifying experimental signatures – deviations from expected behavior, anomalies in correlation functions – that unequivocally demonstrate the existence of these diabolical points. It is worth remembering that every deviation, every outlier, represents not a failure of the theory, but an opportunity to uncover hidden dependencies.

Ultimately, the study of phase diagrams is a humbling exercise. The more precisely one maps the boundaries between phases, the more apparent becomes the inherent complexity lurking within. Perhaps the ultimate goal isn’t to find order, but to understand the principles governing its fleeting, fragile existence.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10783.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Darkwood Trunk Location in Hytale

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- How To Watch A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms Online And Stream The Game Of Thrones Spinoff From Anywhere

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Hytale: Upgrade All Workbenches to Max Level, Materials Guide

- Olympian Katie Ledecky Details Her Gold Medal-Winning Training Regimen

- Shonda Rhimes’ Daughters Make Rare Appearance at Bridgerton Premiere

- RHOBH’s Jennifer Tilly Reacts to Sutton Stracke “Snapping” at Her

- Daredevil Is Entering a New Era With a Chilling New Villain (And We Have A First Look) (Exclusive)

- Matt Damon’s Wife Thought Ben Affleck Was the Cute One Before Meeting

2026-01-20 18:14