Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research explores the dynamic interplay between complexity and order in a model of associative memory, revealing how networks achieve optimal information storage and recall.

A stochastic exponential Dense Associative Memory model exhibits critical behavior characterized by long-range correlations and non-Markovian dynamics, suggesting a pathway to understanding self-organization in neural systems.

While traditional approaches to understanding neural networks often focus on static storage capacity, the dynamic processes underlying learning remain largely unexplored. This study, ‘Temporal Complexity and Self-Organization in an Exponential Dense Associative Memory Model’, investigates the self-organizing behavior of a stochastic exponential Dense Associative Memory (SEDAM) model through the lens of temporal complexity, revealing regimes characterized by intermittent dynamics and scale-free temporal correlations. Specifically, we demonstrate that these networks exhibit a critical region where noise intensity and memory load interplay to induce spontaneous self-organization, exhibiting non-Markovian behavior. How might these findings inform the development of more robust and adaptive artificial and biological neural systems capable of complex information processing?

The Edge of Chaos: A Delicate Balance

Conventional neural networks are frequently designed to achieve stable states, prioritizing reliable and predictable outputs. However, this stability can inadvertently restrict the network’s capacity to adapt to novel or unexpected inputs. By settling into defined patterns, these models may struggle with generalization and exhibit limited learning potential when faced with data significantly different from their training set. This rigidity arises from the minimization of change within the network’s parameters, hindering its ability to explore diverse solutions and respond effectively to dynamic environments. Consequently, a focus on stability, while beneficial for certain applications, can inadvertently create a system that is less flexible and less capable of complex problem-solving than one operating with a greater degree of plasticity.

The brain, and increasingly artificial neural networks, may function most efficiently not in states of rigid stability or chaotic randomness, but at a critical point – the ‘edge of chaos’. This state isn’t about instability; rather, it represents a delicate balance where the system is maximally sensitive to even the smallest inputs. At criticality, a single neuron firing, or a minor change in data, can trigger a cascade of activity across the entire network, allowing for rapid information processing and flexible adaptation. This heightened responsiveness stems from the emergence of long-range correlations – connections extending far beyond immediate neighbors – enabling the system to integrate information from diverse sources and respond to complex stimuli with remarkable efficiency. Researchers theorize that operating at this critical threshold isn’t merely a beneficial configuration, but potentially a fundamental principle underlying intelligent computation and efficient information transfer in complex systems.

The brain’s remarkable efficiency isn’t simply a matter of fast neurons, but potentially a consequence of operating at a critical state. This criticality manifests as long-range correlations – where events in one brain region can influence distant areas – and an amplified sensitivity to even minor perturbations. Researchers theorize that this heightened sensitivity isn’t noise, but a feature allowing for rapid and flexible information processing. A system at the brink of instability, like a critical state, can integrate diverse inputs and respond quickly to change, potentially explaining the brain’s ability to learn, adapt, and solve complex problems with minimal energy expenditure. This principle suggests that efficient computation isn’t about minimizing all fluctuations, but about harnessing the power of controlled instability and maximizing the flow of information across the system.

Self-Organization: The Emergence of Order

Self-organization is a process whereby structure arises in systems from initially random states without central control or external imposition of order. This contrasts with traditionally engineered systems reliant on pre-defined architectures and top-down regulation. Instead, order emerges from local interactions between components, driven by internal dynamics and feedback loops. These systems exhibit adaptability and robustness as the resulting organization isn’t fixed, allowing for response to changing conditions without requiring redesign of overarching structures. The defining characteristic is the absence of a blueprint; patterns and functionality arise through the collective behavior of the system’s elements.

Criticality, in the context of self-organization, refers to a system’s operational state at the boundary between order and disorder. Systems exhibiting this property demonstrate heightened sensitivity to perturbations, allowing for amplified responses and increased information processing capacity. This sensitivity is not merely reactivity; it facilitates the propagation of small fluctuations into macroscopic, coordinated patterns, effectively enabling the spontaneous emergence of order without central control. Research indicates that systems poised at this “edge of chaos” possess an optimal balance between stability and flexibility, making them particularly susceptible to self-organizing processes and the development of complex behaviors.

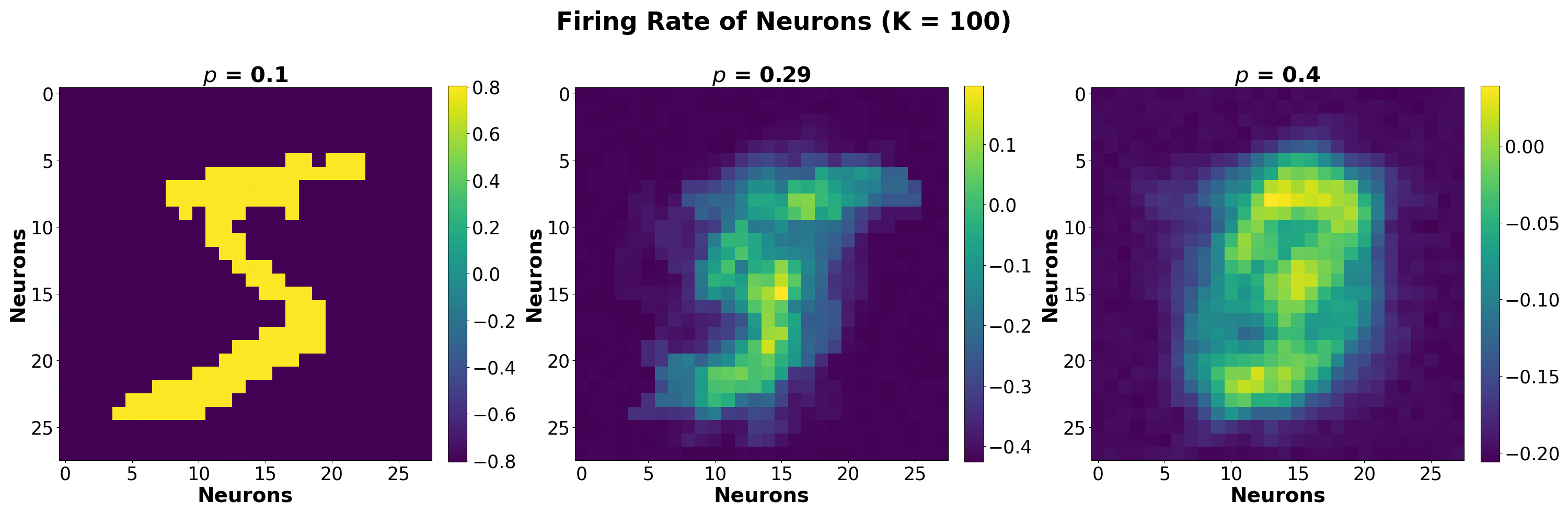

This research utilized a stochastic exponential Dense Associative Memory (SEDAM) model to observe the development of temporal complexity. The SEDAM, a recurrent neural network, was subjected to stochastic inputs, and its dynamic states were analyzed. Results indicated that the model spontaneously generated complex, non-periodic patterns of activity over time, demonstrating an increase in the system’s temporal complexity without external control. These emergent temporal dynamics support the principle that self-organization arises in systems operating near criticality, as the SEDAM’s stochastic nature and dense connectivity facilitate this behavior.

Neural Intermittency: Bursts and Silences in Activity

Neural intermittency describes the observed pattern of alternating periods of high and low activity within neural systems. Rather than maintaining a constant level of firing, neurons cycle between periods of relative silence, or quiescence, and brief, intense bursts of activity. This is not random; the transitions between these states are dynamically regulated and contribute to information processing. The prevalence of intermittency has been documented across various brain regions and scales, from single neuron behavior to large-scale network oscillations, suggesting it is a fundamental property of neural computation. This dynamic switching between active and silent states allows for efficient resource allocation and may enhance the signal-to-noise ratio in neural communication.

Neural intermittency, the alternating pattern of active bursts and silent periods, is fundamentally driven by the reciprocal interaction of excitatory and inhibitory processes within neural networks. Excitatory neurons increase the probability of firing in their postsynaptic targets, while inhibitory neurons decrease this probability. This creates a dynamic equilibrium; increased excitation leads to bursts of activity, which subsequently activate inhibitory neurons, suppressing further excitation and initiating periods of quiescence. The strength and timing of these opposing forces, determined by synaptic weights and neuronal properties, establish the characteristic on/off switching observed in intermittent neural activity. This balance isn’t static, but rather fluctuates based on network state and incoming stimuli, contributing to the adaptability and computational power of neural systems.

Coincidence detection, realized through mechanisms like spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), fundamentally shapes intermittent neural activity. Neurons that fire synchronously experience strengthened synaptic connections, increasing the probability of future coincident firing. This positive feedback loop contributes to the formation of transient, self-sustained bursts of activity. Conversely, asynchronous firing leads to synaptic depression, reinforcing periods of quiescence. The precise timing of pre- and post-synaptic spikes dictates the magnitude and sign of synaptic modification, establishing a dynamic equilibrium between excitation and inhibition that is critical for maintaining these intermittent patterns. This process isn’t simply a matter of rate coding; it’s the temporal structure of neuronal firing – specifically, the occurrence of near-simultaneous activity – that drives the establishment and stability of bursts and silences within neural networks.

Neural Avalanches: Scaling Laws and Efficiency

Neural avalanches are characterized by coordinated, transient bursts of neural activity across populations of neurons. The defining feature of these avalanches is their scale-free nature, meaning that burst sizes – measured by the number of activated neurons or the duration of activity – are not limited to a specific range. Instead, bursts of all sizes occur with a frequency that follows a power-law distribution P(s) \propto s^{-\alpha}, where ‘s’ represents the burst size and ‘α’ is the scaling exponent. This implies that small avalanches are far more common than large ones, but large avalanches, while rare, are not statistically impossible and occur at predictable frequencies consistent with the power-law relationship. The observation of scale-free behavior suggests that the system operates near a critical point, maximizing its dynamic range and computational efficiency.

Neural avalanches are directly linked to the principle of intermittency, a property where activity occurs in bursts separated by periods of relative quiescence. This phenomenon isn’t simply a surface-level observation; it represents a macroscopic expression of the underlying dynamic regimes governing neural network activity. Specifically, intermittency arises from the network operating near a critical point, where small perturbations can trigger cascades of activity. These cascades, observable as avalanches, demonstrate that the system isn’t consistently active or inactive, but rather fluctuates between states in a non-trivial manner. The prevalence of intermittent dynamics suggests an efficient use of resources, as the network avoids both constant, energy-intensive firing and complete inactivity that would hinder information processing.

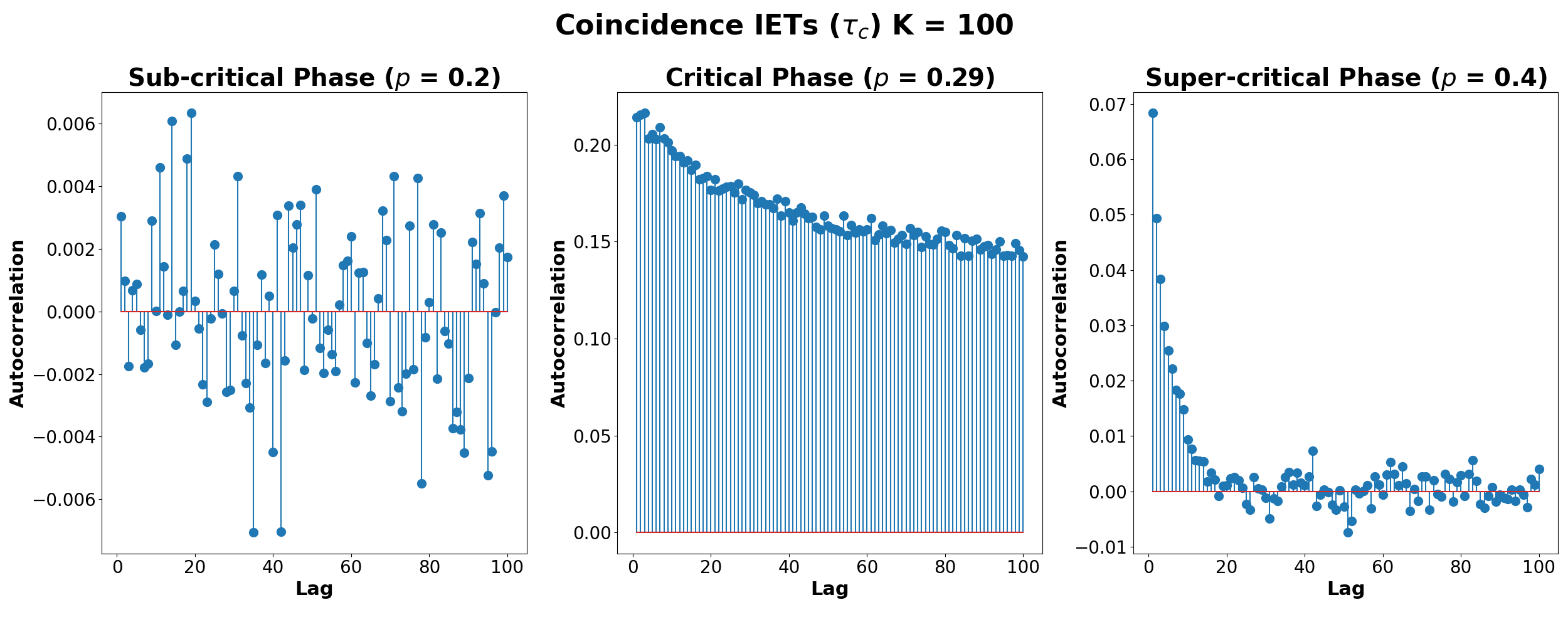

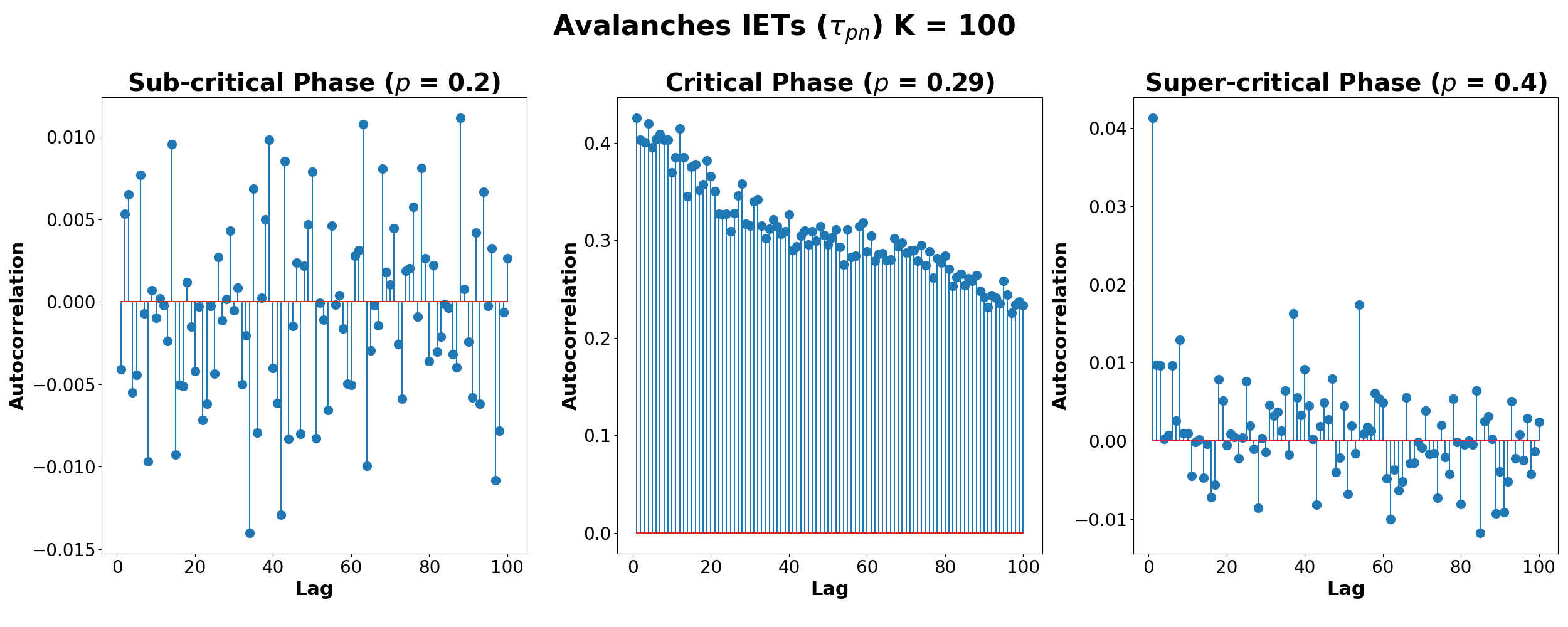

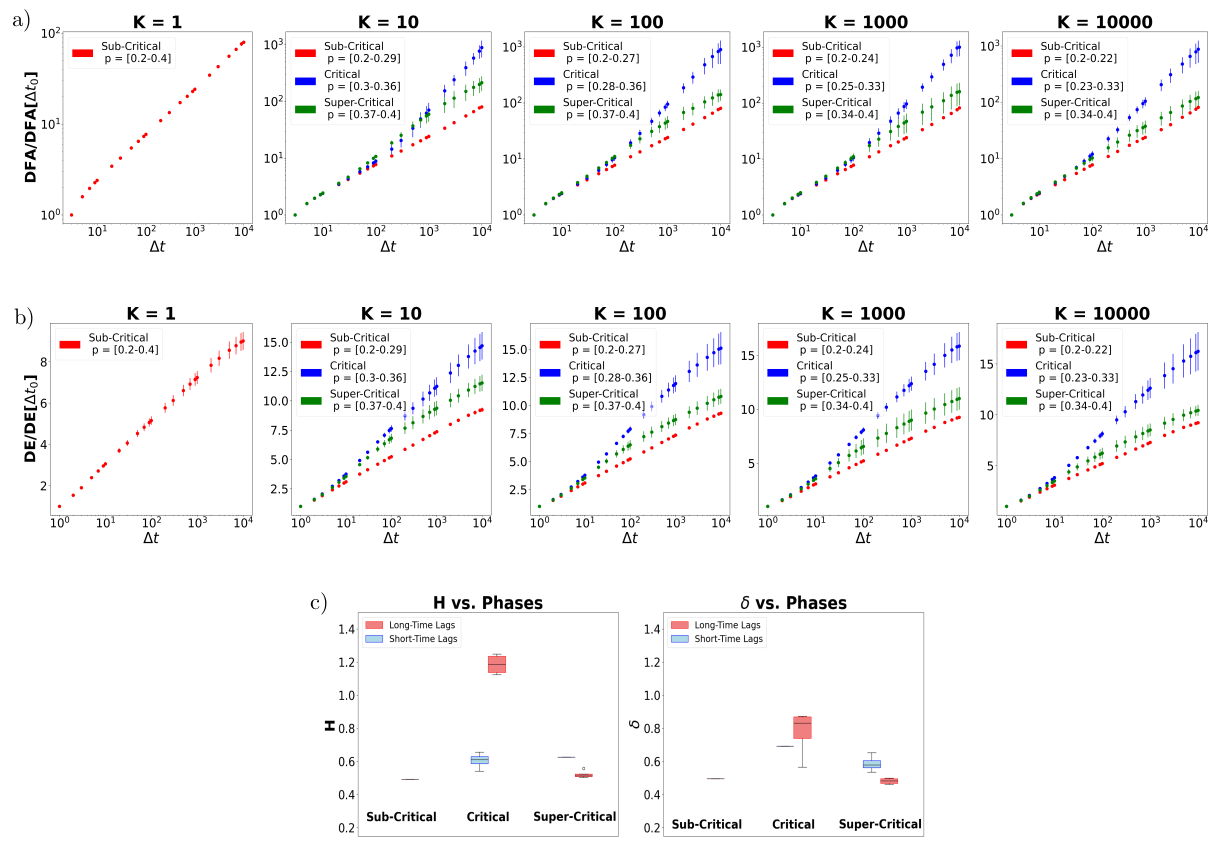

Analysis of neural avalanche dynamics revealed a critical noise intensity range of 0.23 to 0.36. Within this range, both the Hurst exponent (H) and the Similarity Index (δ) exhibited deviations from 0.5, indicating a departure from Gaussian diffusion and the presence of long-range temporal correlations. Specifically, the observed behavior suggests non-Gaussian diffusion processes are occurring during this critical phase. Furthermore, Inter-Event Time (IET) distributions displayed power-law scaling for values of K greater than 1, supporting the presence of scale-free dynamics and self-organized criticality within the neural system.

The study of the SEDAM model reveals a system where order isn’t imposed, but arises from the interactions of its components. The observed critical region, characterized by long-range correlations and non-Markovian dynamics, suggests the system’s capacity for complex computation isn’t a result of centralized control, but rather emerges from local Hebbian learning rules. This echoes Immanuel Kant’s assertion: “Out of sheer inclination, no principle can come.” The model demonstrates that complex behavior isn’t necessarily planned; it’s a natural consequence of the system’s inherent dynamics, much like a living organism adapting to its environment. The system is a living organism where every local connection matters, and top-down control often suppresses creative adaptation.

Beyond Static Memories

The investigation of this stochastic exponential Dense Associative Memory model suggests that complexity doesn’t reside in elaborate design, but in the delicate balance achieved at a critical point. The observed non-Markovian dynamics and long-range correlations aren’t properties imposed upon the system, but rather emerge from the local interactions of its components. This reinforces the notion that stability and order emerge from the bottom up; top-down control is merely an illusion of safety. Future work should explore how these critical properties influence the model’s capacity for genuinely novel associations – moving beyond simple recall towards something resembling creative problem-solving.

A significant limitation remains the model’s reliance on idealized Hebbian learning. Biological neural networks are awash in modulation, noise, and competing plasticity mechanisms. Incorporating these complexities, rather than striving for pristine mathematical elegance, may reveal whether the observed self-organization is robust or a fragile artifact of simplification. Furthermore, the model currently treats memory as a static entity. A truly dynamic system must grapple with the inevitable process of forgetting, and how that process interacts with ongoing learning and adaptation.

The pursuit of “intelligent” systems often focuses on building increasingly sophisticated algorithms. Perhaps the more fruitful path lies in understanding how to create conditions where intelligence can emerge spontaneously. This SEDAM model, and others like it, offer a glimpse into that possibility – a suggestion that complexity is not something to be engineered, but something to be cultivated.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11478.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Darkwood Trunk Location in Hytale

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- How To Watch A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms Online And Stream The Game Of Thrones Spinoff From Anywhere

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Hytale: Upgrade All Workbenches to Max Level, Materials Guide

- PS5’s Biggest Game Has Not Released Yet, PlayStation Boss Teases

- Olympian Katie Ledecky Details Her Gold Medal-Winning Training Regimen

- Shonda Rhimes’ Daughters Make Rare Appearance at Bridgerton Premiere

- Katy Perry Shares Holiday Pics With Justin Trudeau & Ex Orlando Bloom

- Benji Madden Calls Niece Kate Madden a “Bad Ass” in Birthday Shoutout

2026-01-20 19:53