Author: Denis Avetisyan

This review explores the evolving landscape of cryptographic algorithms designed to withstand the threat of quantum computers.

A comprehensive overview of post-quantum cryptography, including foundational algorithms, standardization efforts, and implementation challenges.

The continued advancement of quantum computing presents a fundamental challenge to currently deployed cryptographic systems. ‘Fundamentals, Recent Advances, and Challenges Regarding Cryptographic Algorithms for the Quantum Computing Era’ provides a comprehensive overview of this evolving landscape, detailing both the threat posed by algorithms like Shor’s and the emerging field of post-quantum cryptography. This work synthesizes foundational concepts, explores diverse post-quantum algorithm families-including lattice-based and hash-function-based approaches-and critically examines ongoing standardization efforts, notably the NIST process. As we navigate this transition, how can we best ensure a secure and interoperable cryptographic infrastructure for the post-quantum era?

The Quantum Threat: Unraveling the Foundations of Digital Security

The bedrock of modern internet security, asymmetric algorithms such as RSA and AES, face an existential threat from the rapid advancements in quantum computing. These algorithms rely on the computational difficulty of certain mathematical problems – like factoring large numbers or the discrete logarithm problem – for their security. However, Shor’s algorithm, a quantum algorithm, can efficiently solve these problems, effectively breaking the encryption that protects vast amounts of sensitive data. While currently, quantum computers capable of mounting such attacks are still under development, the potential for decryption is not theoretical; stored communications encrypted with these algorithms are already vulnerable to ‘harvest now, decrypt later’ attacks. This means adversaries can intercept encrypted data today, anticipating the future availability of quantum computers to unlock the information, posing a significant and growing risk to confidentiality, integrity, and authentication across digital landscapes.

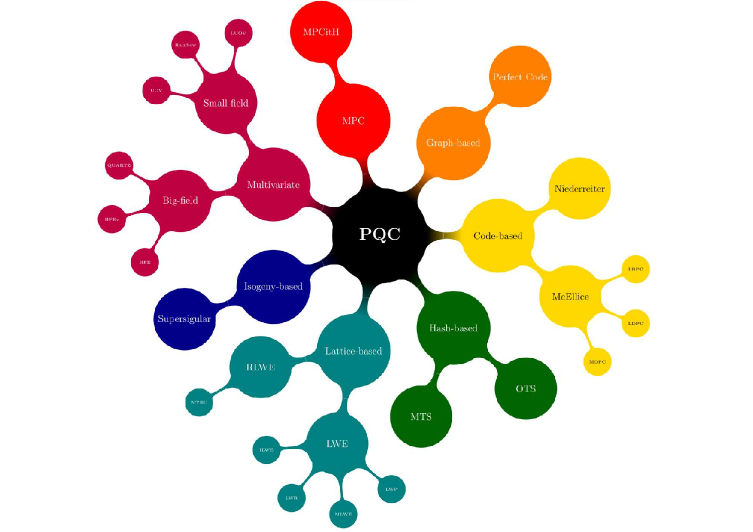

The anticipated arrival of fault-tolerant quantum computers demands a fundamental reassessment of modern cryptography. Current public-key systems, such as RSA and those employing elliptic curves, rely on the computational difficulty of certain mathematical problems – problems that quantum algorithms, notably Shor’s algorithm, can solve efficiently. This doesn’t merely suggest a need for larger key sizes; it signifies an inherent weakness. Consequently, the field is actively transitioning towards post-quantum cryptography (PQC), exploring algorithms believed to be resistant to both classical and quantum attacks. These algorithms, often based on lattice problems, code-based cryptography, multivariate equations, or hash functions, represent a significant departure from established methods and require substantial validation and standardization efforts. The shift to PQC isn’t simply a technical upgrade; it’s a proactive measure to safeguard the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of digital information in a future where quantum computers pose a credible threat to existing security infrastructure, ensuring continued trust in online transactions and data protection.

The potential compromise of digital security by quantum computers extends far beyond simply decrypting confidential information. While breaking encryption algorithms like RSA threatens the privacy of transmitted data, the implications for data integrity and authenticity are equally severe. Secure communication relies not only on keeping messages secret, but also on verifying that the message hasn’t been tampered with during transit and that it genuinely originates from the claimed sender. Quantum attacks jeopardize the digital signatures and hashing algorithms that guarantee these assurances, potentially allowing malicious actors to forge documents, impersonate legitimate entities, and manipulate critical systems. This widespread vulnerability impacts all facets of secure communication, from financial transactions and healthcare records to governmental communications and national security infrastructure, demanding a proactive and comprehensive approach to quantum-resistant cryptography.

Forging a New Shield: The Rise of Post-Quantum Cryptography

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) represents a proactive approach to cryptographic security, addressing the potential threat posed by the development of large-scale quantum computers. Current public-key cryptographic algorithms, such as RSA and ECC, are vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm when executed on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer. PQC aims to replace these algorithms with new methods that are believed to be secure against attacks utilizing both classical computing resources and known quantum algorithms. This resistance is achieved by basing security on mathematical problems that are considered intractable for both types of computers, ensuring continued confidentiality and integrity of digital communications and data storage even in a post-quantum computing landscape. The focus is not on creating algorithms immune to all future attacks, but on shifting the computational difficulty to problems where no known efficient algorithm exists for either classical or quantum computers.

Currently, research into Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) is not focused on a single algorithmic solution, but rather explores several distinct mathematical approaches. Code-based cryptography, exemplified by the McEliece system, relies on the difficulty of decoding general linear codes. Lattice-based cryptography, including algorithms like Kyber and Dilithium, leverages the presumed hardness of problems involving lattices – specifically, finding short vectors within them. Finally, multivariate schemes construct systems based on the difficulty of solving systems of multivariate polynomial equations over finite fields. Each of these approaches presents unique strengths and weaknesses regarding key size, computational performance, and resistance to potential attacks, driving ongoing evaluation and standardization efforts.

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms rely on the inherent difficulty of solving specific mathematical problems for quantum computers. Unlike current public-key cryptography, which depends on the computational hardness of integer factorization or the discrete logarithm problem – both vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer – PQC algorithms are built around problems believed to be resistant to known quantum attacks. These problems include decoding general linear codes (as used in the McEliece cryptosystem), solving the learning with errors (LWE) problem which underpins many lattice-based schemes like Kyber and Dilithium, and solving systems of multivariate polynomial equations. The security of these algorithms is predicated on the assumption that finding solutions to these problems requires exponential time, even with the use of quantum algorithms like Grover’s algorithm, making them computationally infeasible for attackers.

Balancing the Equation: Security, Performance, and Implementation

All cryptographic systems, including Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms, exhibit a fundamental trade-off between security strength, computational performance, and implementation complexity. Increasing the security level, typically measured by the key size or the number of computational rounds, invariably leads to increased computational cost, impacting both encryption/decryption speeds and resource requirements. Conversely, optimizing for performance often necessitates reducing security parameters or employing less robust algorithms. Furthermore, complex algorithms, while potentially offering higher security, demand more intricate implementations, increasing the likelihood of vulnerabilities arising from coding errors or side-channel attacks. This necessitates a careful balancing act during cryptographic system design to achieve an acceptable compromise between these competing factors, tailored to the specific application and its constraints.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) and Multi-Party Computation (MPC) represent advanced cryptographic techniques that prioritize data privacy by enabling computations on encrypted data or distributed data without revealing the underlying values. FHE allows operations to be performed directly on ciphertext, yielding an encrypted result that, when decrypted, matches the result of the same operations performed on the plaintext. MPC enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function over their private inputs while keeping those inputs confidential. However, both techniques introduce substantial computational overhead; FHE is currently several orders of magnitude slower than traditional encryption and decryption, and MPC requires significant communication and computation to ensure privacy and correctness. This resource intensity limits their practical deployment in many applications, despite their strong privacy guarantees.

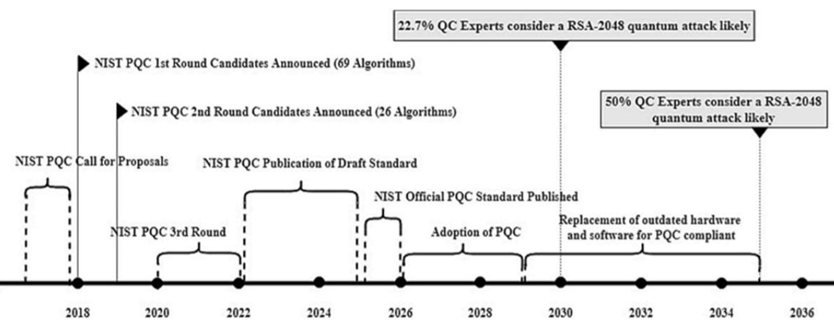

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) initiated a standardization process in 2016 to identify Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms resilient to attacks from quantum computers. This multi-round process involved public solicitations for submissions, rigorous evaluation based on security, performance, and implementation characteristics, and public feedback periods. NIST established specific security levels – Level 1, Level 3, and Level 5 – representing increasing levels of protection against known attacks, influencing algorithm selection criteria. Following multiple rounds of analysis and refinement, NIST announced its initial selections for standardization in 2022, encompassing algorithms like CRYSTALS-Kyber for key encapsulation and CRYSTALS-Dilithium, FALCON, and SPHINCS+ for digital signatures, with further candidates remaining under evaluation for potential future standardization.

Layered Defenses: Hybrid Cryptography and the Future of Communication

Hybrid cryptography represents a pragmatic approach to securing data in the face of advancing quantum computing capabilities. This method doesn’t immediately discard currently reliable classical encryption – algorithms like RSA and ECC – but rather layers them with newly developed post-quantum cryptography (PQC). By combining the strengths of both, a system gains resilience; even if a quantum computer were to break the classical component, the PQC element would still provide confidentiality. This layered defense is particularly vital during the transition period, as the standardization and widespread implementation of PQC take time. It mitigates the risk of data being intercepted and stored now, only to be decrypted later when sufficiently powerful quantum computers become available, ensuring long-term data security without requiring an immediate and potentially disruptive overhaul of existing cryptographic infrastructure.

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) represents a potentially revolutionary approach to secure communication, promising information-theoretic security based on the laws of physics rather than computational assumptions. Unlike classical cryptographic methods vulnerable to increasingly powerful computers, QKD utilizes the quantum properties of photons to establish a secret key between two parties – any attempt to intercept the key inevitably introduces detectable disturbances. However, realizing this theoretical promise presents significant hurdles. Photon loss and decoherence limit transmission distances, requiring trusted nodes or quantum repeaters – technologies still under development – for long-range communication. Furthermore, the complex and specialized equipment needed for QKD, including single-photon sources and detectors, is expensive and requires precise calibration and maintenance, hindering widespread deployment beyond niche applications and controlled environments.

The advent of quantum computing presents a significant threat to currently employed cryptographic systems, necessitating a proactive shift towards quantum-resistant solutions. Safeguarding critical infrastructure – encompassing power grids, communication networks, and essential services – demands the immediate integration of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) and, strategically, hybrid approaches that blend classical and quantum-resistant algorithms. Financial transactions, increasingly reliant on digital security, are equally vulnerable and require robust protection against potential decryption of sensitive data. Perhaps most importantly, the personal data of individuals – medical records, financial information, and private communications – must be shielded from future quantum-based attacks. Successful deployment of these new cryptographic standards is not merely a technological upgrade, but a fundamental requirement for maintaining trust and stability in the digital age, ensuring continued confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information across all sectors.

The Mathematical Foundation: Post-Quantum Security in Detail

Post-quantum cryptography (PQC) doesn’t conjure security from nothing; instead, it grounds its defenses in the established difficulty of certain mathematical problems. Algorithms like those based on lattices – multidimensional, regularly spaced arrangements of points – and codes, such as those used in error-correcting codes, present computational challenges believed to be intractable for even the most powerful quantum computers. The security isn’t absolute, but hinges on the assumption that solving these problems requires exponentially increasing computational resources. For example, finding the closest vector within a lattice – the shortest vector problem SVP – or decoding a general linear code are problems for which no efficient classical or quantum algorithms are currently known. Therefore, PQC algorithms transform data encryption and decryption into instances of these hard mathematical problems, offering a pathway to secure communication even in a world with quantum computers.

Bootstrapping represents a pivotal advancement within Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), addressing the inherent noise accumulation that arises during computations on encrypted data. Essentially, this technique allows for the ‘refreshing’ of a ciphertext – effectively reducing the noise without decrypting the underlying information. Each homomorphic operation introduces a small amount of error; without a mechanism to control this, successive computations would render the result undecipherable. Bootstrapping operates by performing a homomorphic evaluation of the decryption circuit on the ciphertext itself. This process yields a new ciphertext that encrypts the same value as the original, but with significantly reduced noise. Critically, this can be repeated an unlimited number of times, theoretically enabling any computation – no matter how complex – to be performed directly on encrypted data without ever revealing it in plaintext. The efficiency of bootstrapping remains a key area of research, as it currently represents a significant computational overhead, but ongoing advancements promise to unlock the full potential of privacy-preserving computation.

The landscape of cryptographic security is not static; it demands perpetual advancement in both techniques and the mathematical principles underpinning them. While current post-quantum cryptography (PQC) algorithms offer a promising defense against anticipated quantum computer attacks, their long-term resilience isn’t guaranteed. Emerging threats, unforeseen algorithmic breakthroughs, and the continuous increase in computational power necessitate ongoing investigation into novel cryptographic constructions and a deeper understanding of the mathematical problems that secure them. This research extends beyond simply refining existing algorithms; it requires exploration of entirely new approaches, potentially drawing upon areas like multivariate cryptography or hash-based signatures, and rigorous analysis of their resistance to both classical and quantum attacks. The pursuit of robust security, therefore, relies on a sustained commitment to foundational mathematical research and the development of adaptable cryptographic systems capable of withstanding future challenges.

The pursuit of post-quantum cryptography, as detailed in the study of cryptographic algorithms, inherently embodies a spirit of relentless testing. It’s a deliberate attempt to dismantle established security, not through malice, but through rigorous examination. This process mirrors the hacker’s mindset – understanding a system demands probing its weaknesses. Linus Torvalds aptly stated, “Most good programmers do programming as a hobby, and then they get paid to do it.” This sentiment applies directly to the field; the drive to create quantum-resistant solutions isn’t merely a professional obligation, but a natural extension of the desire to dissect, improve, and ultimately, comprehend the very foundations of digital security.

What Breaks Next?

The pursuit of post-quantum cryptography isn’t about solving security; it’s about iteratively delaying its inevitable compromise. This work lays out the current fortifications, detailing lattice structures, homomorphic schemes, and the ongoing NIST standardization process. But consider the inherent paradox: standardization implies a known target. A clearly defined problem, however complex, is, at its core, simpler to dismantle than an evolving threat. The field must actively court disruption – deliberately probing the limits of these ‘secure’ algorithms, not to find flaws, but to anticipate where the next break will occur.

Quantum key distribution offers a superficially elegant solution, sidestepping algorithmic vulnerability altogether. However, its practical limitations – distance, infrastructure, cost – invite a different kind of attack: economic incentives. The true challenge isn’t merely building unbreakable codes, but creating a system where breaking them is demonstrably more expensive than simply accepting the risk. This demands a shift in focus – from algorithmic purity to holistic system resilience, accounting for human fallibility and market forces.

Ultimately, the longevity of any cryptographic scheme rests on its ability to become obsolete before it is broken. The field should embrace a philosophy of planned obsolescence, continuously designing algorithms destined for eventual replacement. The goal isn’t perpetual security, but a perpetual cycle of adaptation-a restless pursuit of the next temporary shield against an ever-evolving assault.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.18413.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Donkey Kong Country Returns HD version 1.1.0 update now available, adds Dixie Kong and Switch 2 enhancements

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- When to Expect One Piece Chapter 1172 Spoilers & Manga Leaks

- Sega Insider Drops Tease of Next Sonic Game

- Fantasista Asuka launches February 12

- Hytale: Upgrade All Workbenches to Max Level, Materials Guide

- 10 Ridley Scott Films With the Highest Audience Scores on Rotten Tomatoes

- Star Trek 4’s Cancellation Gives the Reboot Crew an Unwanted Movie Record After TOS & TNG

- Arc Raiders Guide – All Workbenches And How To Upgrade Them

2026-01-27 08:36