Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a novel orbital-free density functional theory method offering a computationally efficient way to model the electronic structure of materials at extreme temperatures and densities.

The SKANEX method achieves Kohn-Sham DFT accuracy for warm dense matter, enabling simulations of electronic structure under conditions relevant to astrophysics, planetary science, and inertial confinement fusion.

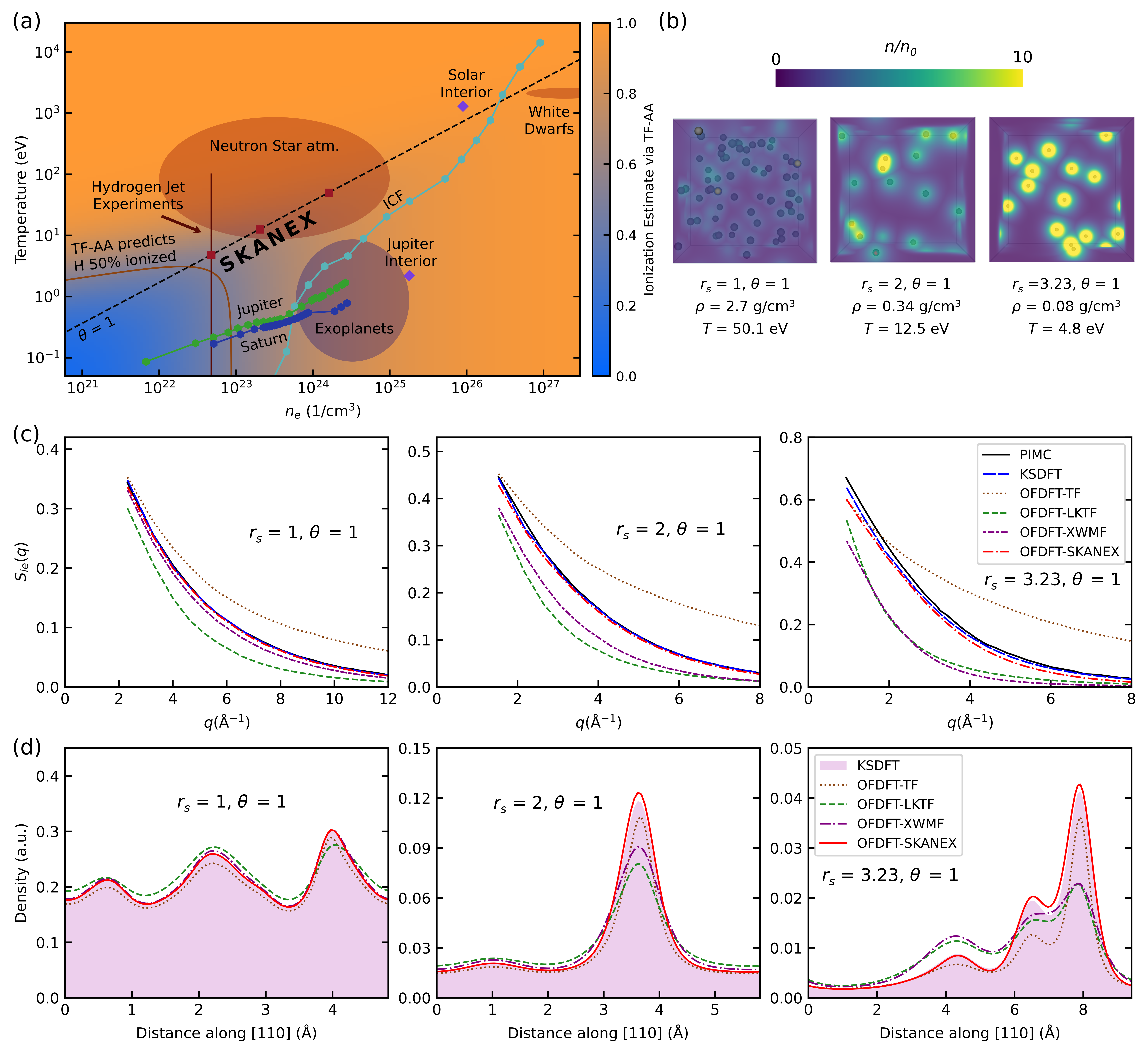

Interpreting experimental data from extreme conditions-such as those found in stellar interiors and fusion experiments-remains challenging for many theoretical models. This limitation motivates the work presented in ‘Unlocking the Power of Orbital-Free Density Functional Theory to Explore the Electronic Structure Under Extreme Conditions’, which introduces SKANEX, a novel Kohn-Sham-assisted orbital-free density functional theory framework. SKANEX achieves Kohn-Sham density functional theory-level accuracy for key electronic structure properties-including densities, structure factors, and equations of state-while offering substantial computational speedups. By enabling efficient simulations of warm dense matter, does this approach pave the way for more accurate and scalable modeling of matter under truly extreme conditions?

Deconstructing Reality: The Limits of Conventional Modeling

The properties of any material – its strength, conductivity, color, and even how it interacts with light – are fundamentally dictated by the behavior of its electrons. Therefore, accurately modeling electronic structure is paramount to predicting and understanding material behavior. However, this accuracy comes at a significant computational cost; simulating the interactions of many electrons requires processing power that scales rapidly with system size. Current, highly accurate methods often become intractable for all but the simplest materials or systems, limiting the ability to investigate complex phenomena or predict the behavior of materials under extreme conditions. This computational bottleneck necessitates the development of alternative approaches that can balance accuracy with efficiency, opening new avenues for materials discovery and scientific advancement.

Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KSDFT), a cornerstone of materials modeling, encounters significant hurdles when applied to warm dense matter (WDM) and high-energy-density physics. The computational cost of KSDFT scales unfavorably with system size – often as O(N^3), where N represents the number of electrons – due to the need to solve the Kohn-Sham equations self-consistently. In WDM, characterized by high temperatures and densities, and in the even more extreme conditions of high-energy-density physics, the number of electrons involved becomes immense. This dramatically increases the computational burden, making accurate simulations prohibitively expensive and, in many cases, entirely impractical with traditional computational resources. The fundamental challenge lies in accurately describing the complex many-body interactions within these systems while maintaining a reasonable computational throughput, prompting researchers to explore alternative theoretical frameworks and computational strategies.

The inability to accurately model electronic structure at extreme conditions significantly impacts multiple scientific frontiers. Astrophysical phenomena, such as those occurring within stellar interiors and planetary cores, involve matter compressed to densities and temperatures where conventional methods falter. Similarly, the pursuit of controlled nuclear fusion relies on understanding plasma behavior under immense pressure and heat, conditions where current simulations are often compromised by computational bottlenecks. Furthermore, national security applications, including stockpile stewardship and the modeling of high-energy-density materials, demand reliable predictions of material response under shock compression and other extreme events-predictions that are presently limited by the fidelity of available electronic structure calculations. Consequently, advancements in computational methods are crucial not only for expanding fundamental knowledge but also for addressing pressing technological and security challenges.

The pursuit of computationally efficient alternatives to traditional electronic structure modeling has become paramount in fields grappling with extreme conditions. Current methods, while accurate for many materials, struggle with the scaling demands of warm dense matter and high-energy-density physics – regimes characterized by intensely compressed materials and elevated temperatures. Researchers are actively exploring techniques such as orbital-free density functional theory and machine learning-based approaches to circumvent these limitations. These innovative strategies aim to achieve a favorable balance between computational cost and predictive accuracy, enabling detailed simulations of phenomena relevant to the interiors of gas giants, inertial confinement fusion, and the behavior of materials under shock compression. Success in this area promises to unlock a deeper understanding of matter at its most extreme, with far-reaching implications for both fundamental science and applied technologies.

Stripping Away the Complexity: Orbital-Free DFT as a System Reset

Orbital-Free Density Functional Theory (OFDFT) represents a computational advantage over traditional Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KSDFT) by eliminating the need to determine and solve the Kohn-Sham equations, which scale approximately as O(N^3) , where N is the number of basis functions. KSDFT requires calculating and manipulating single-particle orbitals, a process absent in OFDFT. Instead, OFDFT directly calculates the total energy as a functional of the electron density, \rho(r) , significantly reducing computational cost and allowing for simulations of larger systems and longer timescales. This efficiency derives from operating directly on the density, a three-dimensional quantity, compared to the four-dimensional Kohn-Sham orbitals.

The accuracy of Orbital-Free Density Functional Theory (OFDFT) calculations is directly dependent on the quality of the approximation used for the non-interacting free-energy functional, F_{s}[n], where n represents the electron density. This functional dictates the kinetic energy contribution, which is not explicitly calculated in OFDFT as it is in Kohn-Sham DFT. Unlike KSDFT, which relies on single-particle orbitals, OFDFT expresses the kinetic energy directly as a functional of the density. Consequently, errors in approximating F_{s}[n] propagate significantly into the total energy and derived properties, limiting the overall accuracy of the method. Improvements in the non-interacting free-energy functional are therefore the primary focus of OFDFT development.

Early approximations to the non-interacting free-energy functional in Orbital-Free Density Functional Theory, most notably the Thomas-Fermi model, offer computational simplicity but suffer from significant inaccuracies. The Thomas-Fermi model, which approximates the kinetic energy as a function of the electron density, fails to accurately represent the rapidly oscillating nature of the true kinetic energy, leading to substantial errors in calculated energies and structural properties. Specifically, it poorly describes the derivative discontinuity of the exchange-correlation potential and exhibits significant self-interaction error. Consequently, while computationally inexpensive, the Thomas-Fermi model and its immediate successors are generally unsuitable for quantitative calculations on most materials and typically require substantial modifications or more sophisticated functionals to achieve acceptable accuracy.

The XWMF (Xie-Wang-Martin-Fei) functional represents an improvement over earlier orbital-free density functionals by incorporating gradient corrections and a non-local correlation term, leading to enhanced accuracy in predicting ground-state properties. However, current implementations of XWMF still exhibit errors-typically around 10-20% for total energies-when compared to Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KSDFT) results for complex systems. Ongoing research focuses on refining the parameters within the XWMF functional, particularly the range-separation parameter and the treatment of semi-local exchange-correlation, to minimize these discrepancies and approach the level of accuracy achieved by KSDFT methods. This optimization includes benchmarking against extensive datasets of molecular and solid-state systems and employing advanced numerical techniques to improve the functional’s performance for diverse chemical environments.

Reverse Engineering Accuracy: The SKANEX Optimization Protocol

SKANEX represents a new approach within the orbital-free density functional theory (OFDFT) framework, distinguished by its direct optimization of the non-interacting free-energy functional. Unlike traditional OFDFT methods that rely on approximations for the kinetic energy, SKANEX iteratively adjusts the parameters within this functional to minimize the discrepancy between electron densities calculated using OFDFT and those obtained from Kohn-Sham density functional theory (KSDFT). This optimization process aims to replicate the accuracy of KSDFT, which is considered the gold standard for electronic structure calculations, while leveraging the computational efficiency inherent in OFDFT methods by avoiding the calculation of single-particle orbitals. The functional being optimized takes the general form F_{K}[\rho] = T_{K}[\rho] + V_{ext}[\rho], where T_{K}[ρ] represents the kinetic energy functional and V_{ext}[ρ] is the external potential.

Within the SKANEX framework, Powell’s method serves as the optimization algorithm used to refine the non-interacting free-energy functional. This iterative process minimizes the difference between the electron density obtained from the orbital-dependent functional theory (OFDFT) calculation and that of the Kohn-Sham density functional theory (KSDFT) reference. Specifically, Powell’s method adjusts parameters within the OFDFT functional until a convergence criterion, based on the density difference, is met. The method is a derivative-free optimization technique, making it suitable for complex functionals where analytical gradients are unavailable, and it efficiently searches for optimal functional parameters by combining directional conjugate gradients.

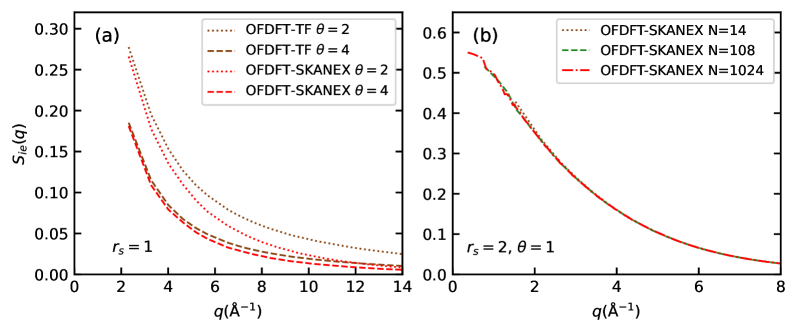

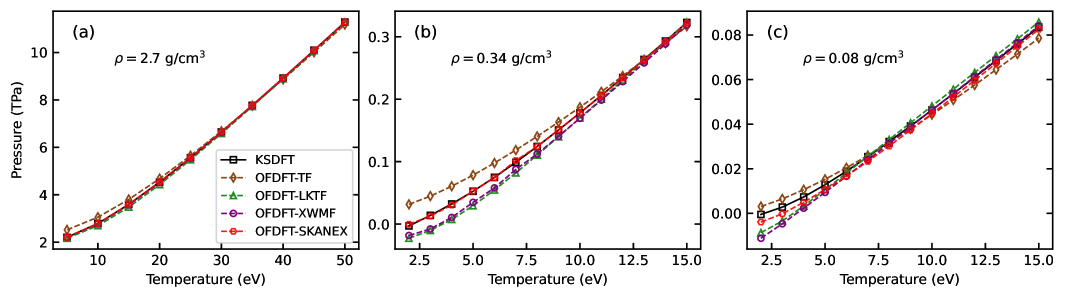

Employing the SKANEX method enables computational simulations to reach the accuracy levels of Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KSDFT) while achieving significant performance gains. Benchmarking indicates a computational speedup ranging from 10 to 1000 times faster than traditional KSDFT calculations. This acceleration is achieved by directly optimizing the non-interacting free-energy functional within SKANEX to closely match the results obtained from KSDFT, allowing for efficient and accurate modeling of electronic structure.

The implementation of SKANEX calculations is currently facilitated by software packages such as ATLAS, which provides the necessary tools and algorithms for performing optimized effective density functional theory (OFDFT) simulations. While ATLAS supports SKANEX, Quantum ESPRESSO remains the established standard for Kohn-Sham density functional theory (KSDFT) calculations and serves as the benchmark against which SKANEX results are typically compared for validation and accuracy assessment. This allows researchers to verify that SKANEX achieves the targeted KSDFT-level accuracy while benefiting from its computational speedup.

Probing the Boundaries of Matter: SKANEX and the Future of Simulation

SKANEX provides a robust method for calculating the Rayleigh Weight, a crucial indicator of how electrons are distributed within a material and a direct probe of its electronic structure. This quantity, sensitive to the degree of electron localization, offers insights into material behavior that are often obscured by approximations in traditional computational methods. By accurately determining the Rayleigh Weight, SKANEX enables researchers to map the evolving electronic landscape of matter under extreme conditions – high pressures and temperatures – where electrons are no longer bound to individual atoms in the conventional sense. The method’s precision allows for a more nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between electron behavior and macroscopic material properties, offering a pathway to validate theoretical models and predict the behavior of matter in regimes previously inaccessible to detailed study.

The ability to probe electron behavior under extreme conditions – those characterized by immense pressure and temperature – represents a significant advancement facilitated by computational methods like SKANEX. Traditional techniques often falter when faced with the complexities arising from highly compressed matter, where electron correlation effects become dominant and materials exhibit properties drastically different from their everyday counterparts. SKANEX, however, offers a pathway to investigate these previously inaccessible regimes, allowing researchers to map the changes in electronic structure and understand how electrons respond to intense stimuli. This detailed understanding is crucial for modeling phenomena found within planetary interiors, such as those of gas giants, and for simulating the behavior of materials subjected to the conditions of high-energy-density physics, including those relevant to inertial confinement fusion and impacts.

Recent application of the SKANEX method to beryllium at extreme compression-specifically, 23 grams per cubic centimeter-has yielded a density determination strikingly consistent with results from Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) calculations. This finding is particularly significant as it diverges from prior predictions based on conventional chemical models, which estimated beryllium’s density under such conditions to be approximately 30 g/cm³. The discrepancy highlights the limitations of earlier approaches in accurately capturing the complex electronic behavior of matter at high densities, and underscores SKANEX’s ability to provide a more reliable assessment of material properties in regimes inaccessible to traditional methods, offering crucial insights into warm dense matter and high-energy-density physics.

SKANEX represents a significant advancement in the modeling of matter under extreme conditions, specifically warm dense matter and high-energy-density physics. Previous computational approaches often faced a trade-off: either achieving high accuracy at a prohibitive computational cost, or sacrificing precision for feasibility. SKANEX overcomes this limitation by employing a novel methodology that maintains a robust level of accuracy while dramatically improving computational efficiency. This allows researchers to explore a wider range of densities, temperatures, and pressures – regimes crucial for understanding phenomena in astrophysical environments, planetary interiors, and inertial confinement fusion. The enhanced capabilities facilitated by SKANEX not only refine existing simulations but also open doors to investigating previously inaccessible physical scenarios, promising new insights into the fundamental behavior of matter at its most extreme.

SKANEX represents a significant advancement in the ability to model materials under extreme conditions, offering a powerful tool with broad implications for both fundamental science and applied research. The method’s accuracy in determining material properties – such as density and electronic structure – allows for more reliable simulations of environments found in astrophysical phenomena, like the interiors of gas giants or the evolution of stellar remnants. Simultaneously, the insights gained from SKANEX are directly relevant to national security applications, including the modeling of materials subjected to intense shock compression or extreme electromagnetic fields. By providing a robust framework for understanding material behavior at the atomic level, SKANEX empowers researchers to predict and optimize material performance in scenarios previously inaccessible to accurate computational modeling, thereby advancing both scientific discovery and technological innovation.

![The Rayleigh weight of strongly compressed beryllium at 150 eV, as determined by OFDFT calculations, aligns with experimental data obtained from NIF measurements [Tilo_Nature_2023;Dornheim_pop_2025].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.23002v1/x3.png)

The pursuit of SKANEX, as detailed in the study, exemplifies a deliberate dismantling of conventional Kohn-Sham density functional theory to rebuild a more efficient system. This mirrors a core tenet of reverse-engineering-understanding limitations through deconstruction. As Epicurus observed, “It is impossible to live pleasantly without living prudently, honorably, and justly.” Similarly, this research doesn’t simply accept computational bottlenecks; it methodically probes the foundations of existing methods to achieve accuracy without prohibitive cost. The ability to model warm dense matter with DFT-level precision, circumventing the orbital-based calculations, is not merely a technical advancement, but a philosophical confession of imperfection in the original framework – a necessary breach to unlock a better understanding of matter under extreme conditions.

What Lies Beyond?

The introduction of SKANEX isn’t so much a resolution as a carefully constructed demolition of a persistent bottleneck. Orbital-free methods have always promised a shortcut around the computational expense of Kohn-Sham theory, yet consistently stumbled on the accuracy hurdle. This work suggests that hurdle isn’t insurmountable, merely… badly designed. One can’t help but wonder if the relentless pursuit of ever-more-complex exchange-correlation functionals within the conventional framework was, in a sense, a misdirection – a frantic patching of a fundamentally inefficient approach.

Naturally, this invites immediate dismantling. SKANEX, while promising, isn’t a universal solvent. The limitations inherent in any density functional approximation – the approximations are the theory, after all – still apply. The true test lies in extending this approach beyond the relatively well-behaved systems currently examined. Can it reliably navigate the complexities of non-uniform electron densities, strong correlation effects, and the interplay of quantum and thermal effects that characterize truly extreme conditions?

The interesting questions aren’t about refining SKANEX, but about what its success implies. If accuracy can be achieved with a simplified framework, what other cherished assumptions within electronic structure theory are ripe for re-evaluation? Perhaps the goal isn’t to build ever-more-elaborate models of reality, but to identify the minimal scaffolding required to hold it upright-and then, with a satisfying click, to see what falls away.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.23002.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- 10 Most Brutal Acts Of Revenge In Marvel Comics History

- IT: Welcome to Derry Review – Pennywise’s Return Is Big on Lore, But Light on Scares

- Zack Snyder Reveals First Look At New Movie 20 Years In The Making, Following $166M Sci-Fi Disaster

2026-02-03 02:02