Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how strong randomness shapes the behavior of quantum systems at critical points, offering insights into the fundamental principles governing their emergent properties.

Anomalous correlation functions in disordered systems constrain critical behavior and predict specific power-law decays for symmetry-charged operators.

Understanding quantum criticality in strongly disordered systems remains a central challenge in condensed matter physics. This paper, ‘Quantum criticality at strong randomness: a lesson from anomaly’, introduces a novel approach leveraging topological constraints and anomaly considerations to predict universal properties of these systems. Specifically, we demonstrate that the absence of spontaneous symmetry breaking necessitates distinct, slowly decaying correlation functions for operators charged under both exact and average symmetries-a behavior revealed through analysis of the random-singlet Heisenberg chain and disordered free-fermion models. Could these overlooked correlations provide new diagnostic signatures for quantum criticality in realistically disordered materials?

The Illusion of Order: Embracing Material Imperfection

The foundations of much condensed matter physics rest on the assumption of crystalline perfection – a regular, repeating arrangement of atoms extending throughout a material. However, this is an idealization; real materials invariably contain imperfections. These defects, ranging from missing atoms and misplaced ions to variations in chemical composition, introduce disorder at every scale. This isn’t merely a nuisance to be ignored, but a fundamental aspect of material behavior. The presence of disorder dramatically alters electronic properties, vibrational modes, and even the macroscopic characteristics of a substance. While simplified models often treat these imperfections as minor perturbations, the reality is that disorder frequently dictates a material’s ultimate functionality, influencing everything from superconductivity and magnetism to optical response and mechanical strength. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of disorder is paramount to both accurately describing existing materials and designing novel ones with tailored characteristics.

When materials experience ‘strong disorder’ – a condition where randomness in their atomic structure overwhelms predictable patterns – conventional physics struggles to provide accurate descriptions. This isn’t merely a minor deviation from ideal behavior; it fundamentally alters the material’s properties, potentially giving rise to entirely new and unexpected phases of matter. Traditional theoretical methods, built on the assumption of regularity, often break down under these conditions, necessitating innovative approaches. The dominance of random fluctuations can localize electrons, suppress conductivity, or even induce novel forms of magnetism and superconductivity, presenting a rich landscape for materials discovery and pushing the boundaries of condensed matter physics. These exotic phases, born from disorder, hold the promise of functionalities unattainable in perfectly ordered systems.

The pursuit of novel materials with specifically engineered characteristics increasingly relies on harnessing the influence of disorder, yet realizing this potential demands a shift in methodological approaches. Conventional theoretical frameworks, built upon the assumption of crystalline perfection, often falter when confronted with ‘strong disorder’ – the pervasive randomness inherent in many real-world substances. Consequently, researchers are actively developing innovative computational and experimental techniques to bypass these limitations. These new tools allow for the exploration of previously inaccessible regimes, promising the design of materials exhibiting exotic properties – from enhanced superconductivity to tailored optical responses – that would be impossible to achieve within the confines of traditional, order-based paradigms. The ability to accurately model and predict the behavior of strongly disordered systems is therefore not merely an academic exercise, but a crucial step towards a future of materials designed with unprecedented control and functionality.

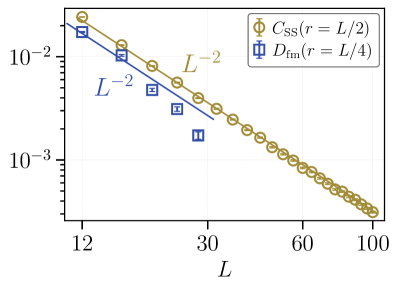

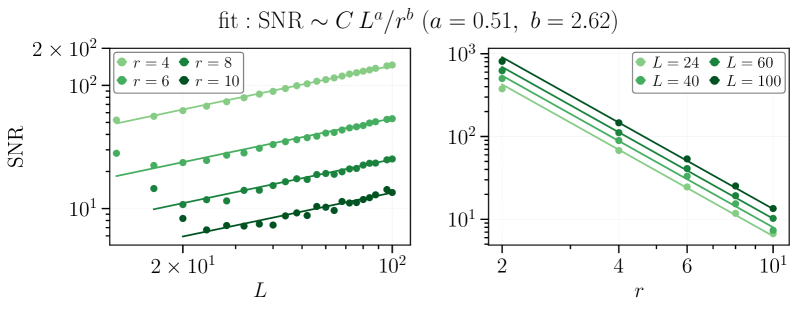

![Finite-size scaling of the sample-connected dimer-dimer correlation function <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">D_{sc}[Eq. 18]</span> reveals power-law behavior in both random Majorana lattices (in 1D and 2D) and random antiferromagnetic Heisenberg chains, as determined by exact diagonalization, DMRG, and strong-disorder RG methods with specified signal-to-noise ratio and distance thresholds.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.02648v1/x12.png)

Beyond Simple Averages: The Ghosts in the Machine

In strongly disordered systems, standard averaging techniques – calculating the mean value of a property across all possible configurations – can produce misleading results known as ‘average anomalies’. This occurs because the distribution of properties is often non-self-averaging; the limit of the average does not converge to the typical value experienced by any single realization of the disorder. Consequently, the averaged quantity may not reflect the behavior of the system in a specific, measurable instance, effectively obscuring the underlying physics. These anomalies arise from the broad distribution of local properties caused by the disorder, where rare, extreme values can significantly influence the average, distorting the overall picture and preventing accurate characterization of the system’s behavior.

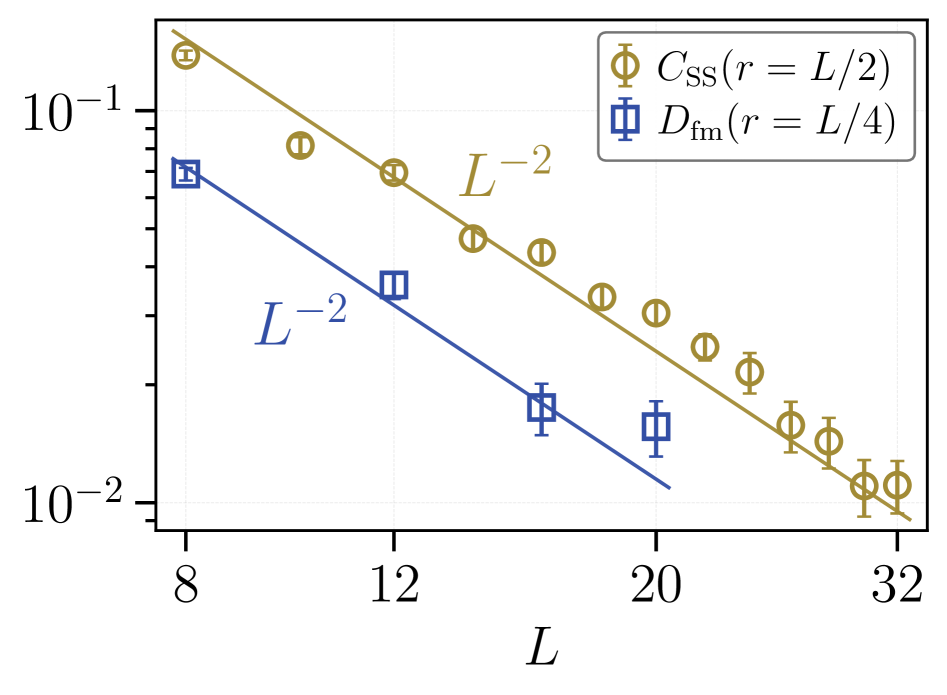

Accurately characterizing systems with disorder necessitates the calculation of correlation functions averaged over all possible realizations of the disorder, collectively known as the ‘disorder ensemble’. The \langle O(r) \rangle obtained from a simple average can be misleading; instead, quantities like the first-moment correlation, \langle O(r) \rangle_{ensemble}, provide a statistically robust measure of how properties at different points r are related. A particularly important example is the Edwards-Anderson (EA) correlator, which quantifies the roughness of the disorder itself and typically exhibits a power-law decay with distance, specifically r^{-2}, indicating short-range correlations in the disorder.

Correlational analysis, as opposed to traditional averaging, provides a more accurate depiction of system behavior in disordered environments by quantifying the impact of disorder on physical properties. Simple averages can be misleading due to ‘average anomalies’ arising from the distribution of disorder; correlators, however, statistically sample over all possible disorder configurations. Specifically, the Edwards-Anderson (EA) correlator, a measure of the overlap between different realizations of the disordered system, exhibits a power-law decay proportional to r^{-2}, where ‘r’ represents spatial separation. This decay rate indicates the characteristic length scale over which disorder correlations persist, and fundamentally differentiates the behavior of these systems from those governed by simple, homogeneous averages.

![Finite-size scaling of correlation functions in a 2D random Majorana lattice reveals power-law behavior for both the Edwards-Anderson correlator <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">C_{EA}[Eq. 3]</span> and the first-moment dimer-dimer correlator <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">D_{fm}[Eq. 6]</span>, as determined by exact diagonalization with <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">200 \times 200</span> disorder realizations and validated by signal-to-noise ratios exceeding 2 (panel a) and 3 (panel b) for <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">r \geq 3</span>.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.02648v1/x6.png)

Deconstructing Complexity: The Strong-Disorder Renormalization Group

The strong-disorder renormalization group (SDRG) is a perturbative technique used to investigate the behavior of systems exhibiting significant disorder. Unlike traditional renormalization group methods which assume weak perturbations, the SDRG is specifically designed for cases where the disorder is a dominant factor influencing system properties. It achieves this by iteratively eliminating degrees of freedom based on energy scales, effectively reducing the complexity of the system while preserving the most relevant low-energy characteristics. This process allows for the systematic calculation of physical observables and the identification of universal behaviors that emerge despite the randomness present in the system, offering a means to address problems intractable with conventional approaches.

The strong-disorder renormalization group (SDRG) operates by sequentially eliminating degrees of freedom based on energy scales; specifically, it removes variables that contribute least to the system’s low-energy physics. This iterative process, termed ‘coarse-graining’, effectively reduces the complexity of the model while retaining the dominant interactions governing behavior at low energies. Each elimination step involves recalculating the relevant parameters of the remaining degrees of freedom, adapting the model to reflect the changed interactions. The procedure continues until a fixed point is reached, or the system becomes sufficiently simplified to allow for analytical treatment, ultimately revealing the low-energy phase diagram and critical properties of the disordered system.

The strong-disorder renormalization group (SDRG), frequently utilized with the replica trick, enables a systematic investigation of how disorder impacts physical systems by averaging over many realizations of the disorder. This technique addresses the inherent complexity of disordered systems, where traditional perturbation theory fails, by focusing on the most relevant degrees of freedom at each renormalization step. Through iterative elimination of weakly coupled degrees of freedom and rescaling of remaining parameters, the SDRG effectively maps a complex, disordered system onto a simpler, effective model. Analysis of the resulting fixed points and flow diagrams allows identification of emergent phases, such as Bose-glass or spin-glass states, and determination of their stability and properties, providing insights inaccessible through direct numerical simulation of the original disordered system.

Symmetry’s Fracture: The Emergence of Novel Phases

Quantum systems, unlike their classical counterparts, can exhibit surprising behavior when subjected to intense disorder. While a classical system maintains symmetries dictated by its underlying structure, strong disorder can induce ‘symmetry anomalies’ at the quantum level, effectively breaking these established rules. This phenomenon arises from quantum fluctuations and the inherent uncertainty in the system’s state, leading to situations where symmetries present in the classical description are no longer respected. The resulting breakdown isn’t a simple loss of order, but a more subtle shift in the system’s fundamental properties, potentially leading to entirely new and unexpected phases of matter with exotic characteristics-a testament to the power of quantum mechanics to defy classical intuition.

Quantum systems subject to strong disorder can exhibit surprising behavior, where symmetries apparent in the underlying classical description are broken at the quantum level – these are known as symmetry anomalies. However, these anomalies aren’t entirely freeform; they are powerfully constrained by the ‘LSM constraint’, a mathematical condition ensuring self-consistency. When this constraint is satisfied, the system can transition into novel, emergent phases of matter, one prominent example being the ‘random singlet phase’. In this peculiar state, electron spins arrange themselves in a highly entangled, yet disordered fashion, forming singlets – pairs of spins with zero total angular momentum – distributed randomly throughout the material. Unlike conventional magnetic order, the random singlet phase lacks long-range correlations, exhibiting a unique form of quantum entanglement that is robust to local perturbations and offers a pathway to understanding more complex quantum phenomena.

Disorder, surprisingly, isn’t always destructive; it can actively sculpt novel quantum phases, including those exhibiting topological order. These phases are distinguished by a robust degeneracy in their ground state – meaning multiple, distinct quantum states require the same minimal energy – a property offering inherent protection against local perturbations. This resilience stems from the collective behavior of quantum particles and is particularly promising for building stable quantum computers. A key characteristic of these disordered topological phases is the behavior of ‘dimer operators’, which describe correlated pairs of particles. Measurements reveal that the correlation between these dimers decays as a power law with distance: the sample-connected correlation function falls off as r^{-4}, while the first-moment correlation function decreases as r^{-3}. This specific decay profile is a signature of long-range entanglement and provides evidence for the existence of exotic quantum states with potential applications in fault-tolerant quantum information processing.

Beyond Perfection: Disorder as a Design Principle

The conventional pursuit of material perfection often overlooks a powerful, yet subtle, force: disorder. Recent investigations reveal that strategically introducing disorder into quantum materials isn’t necessarily detrimental-it can, in fact, unlock a spectrum of novel functionalities. This arises because disorder dramatically alters the electronic landscape, influencing how electrons interact and propagate. Specifically, it can localize electrons – pinning them to certain sites – or create new pathways for conduction that wouldn’t exist in a perfectly ordered crystal. Researchers are now exploring how to control the type and amount of disorder to engineer materials with tailored properties, such as enhanced superconductivity, improved thermoelectric efficiency, or entirely new quantum phenomena. This paradigm shift-viewing disorder not as an enemy, but as a design parameter-promises a revolution in materials science, moving beyond the limitations of pristine crystals and opening doors to previously unimaginable material capabilities.

The ‘free fermion’ model, a cornerstone of condensed matter physics describing non-interacting particles, becomes remarkably insightful when intentionally disrupted by disorder. Introducing imperfections – such as random variations in potential or atomic positions – transforms this seemingly simple system into a powerful platform for probing fundamental physics. Researchers leverage these disordered free fermion systems to test the limits of existing theoretical frameworks and develop novel analytical and numerical tools. The resulting complex behavior – including localization effects where particles become trapped, and the emergence of unusual electronic states – provides a crucial benchmark for understanding more complex, interacting systems. This approach doesn’t merely identify flaws; it utilizes controlled disorder to reveal underlying physical principles and push the boundaries of materials science, offering a unique pathway to explore quantum phenomena and design materials with tailored properties.

The conventional approach to materials science prioritizes crystalline perfection, yet a growing body of research suggests that intentionally introducing disorder can unlock extraordinary functionalities. This isn’t simply about tolerating imperfections; rather, it’s a proactive design principle where controlled randomness becomes a key ingredient. Researchers are discovering that disorder can manipulate electronic states, enhance energy harvesting capabilities, and even induce entirely new phases of matter. For example, strategically placed defects can localize electrons, boosting conductivity in specific directions, or create novel magnetic properties. This paradigm shift moves beyond minimizing flaws to harnessing them, potentially leading to materials with unprecedented performance in areas like superconductivity, solar energy conversion, and quantum computing. The prospect is a future where materials are not defined by their order, but by the carefully engineered chaos within.

The study of quantum criticality within disordered systems, as demonstrated in this paper, inherently involves probing the limits of established frameworks. It’s a process of meticulously dismantling assumptions to reveal underlying mechanisms. This echoes Francis Bacon’s sentiment: “Knowledge is power.” The investigation into anomalies and their constraint on correlation functions isn’t simply about observing critical behavior; it’s about actively reverse-engineering the system’s design through controlled disruption. The precise prediction of power-law decays, stemming from the analysis of these anomalies, is a testament to the power gained by understanding, and ultimately, testing the boundaries of conventional models.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The insistence on anomaly as a constraint-a breaking of neat, predictable behavior-reveals a deeper truth about disordered quantum systems. It’s not enough to simply find critical points; the system will readily offer them. The challenge now lies in mapping the landscape of permissible anomalies. This work, by focusing on correlation functions, provides a critical foothold, but only scratches the surface. A more complete understanding requires extending these techniques to operators with differing charges and spins, effectively building a catalog of allowed disruptions.

The Edwards-Anderson order parameter, while useful, remains a somewhat blunt instrument. True progress demands developing more sensitive probes – observables that can detect subtle shifts in the critical behavior before they manifest as macroscopic anomalies. This may necessitate venturing beyond conventional correlation functions, perhaps exploring higher-order response functions or non-local observables. The current framework hints at universal features, but discerning truly robust principles from system-specific details will require a rigorous, comparative analysis across a wider range of disorder realizations.

Ultimately, the goal isn’t just to describe quantum criticality in disordered systems, but to understand why it happens. Why does randomness so readily drive systems to the brink of order? Is there a fundamental principle at play, or is it simply an emergent phenomenon? The answers, predictably, will likely require dismantling existing assumptions and embracing the inherent unpredictability of complex systems.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.02648.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Rumour: Starfield PS5 to Take Flight Alongside New Expansion Next Year

- G.I. Joe Team Breaks Down Explosive Start to the Dreadnok War (And That Big Time Twist)

2026-02-04 15:05