Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study explores how dark matter and string clouds affect the observable characteristics of charged Hayward black holes, potentially offering pathways to differentiate them from their standard counterparts.

This review analyzes the shadow, geodesics, and quasinormal modes of charged Hayward black holes embedded in dark matter and string cloud environments.

While general relativity successfully describes black holes, their singularity presents a theoretical impasse demanding exploration of more complete models. This is the motivation behind ‘Probing the Charged Hayward Black Hole in Dark Matter and String Cloud Environments through Shadow, Geodesics, and Quasinormal Spectrum’, which investigates a regular black hole solution-the charged Hayward metric-within complex astrophysical environments incorporating dark matter and string clouds. The study reveals that these surrounding elements measurably alter key black hole observables-including shadow size, particle orbits, and quasinormal mode spectra-potentially offering avenues for independent parameter estimation. Could detailed observations of these features ultimately differentiate between standard black holes and these more nuanced, physically motivated alternatives, providing insights into the universe’s exotic components?

Beyond the Event Horizon: Reframing Black Hole Physics

The foundational Schwarzschild solution, a cornerstone of black hole physics, presents inherent limitations when attempting to model realistic astrophysical objects. While mathematically elegant, this classical solution predicts a singularity at the black hole’s center – a point of infinite density and spacetime curvature that breaks down the known laws of physics. Furthermore, the Schwarzschild metric doesn’t account for electric charge, an attribute many real black holes are expected to possess due to accretion of charged particles. This omission creates a disconnect between theoretical predictions and observed phenomena, as charge significantly influences the black hole’s gravitational field and surrounding spacetime. Consequently, the inability of the Schwarzschild solution to address singularities or incorporate charge necessitates the development of more sophisticated models capable of accurately representing the complexities of these enigmatic cosmic entities.

The Charged Hayward black hole presents a significant refinement over classical solutions like Schwarzschild by offering a mathematically ‘regular’ spacetime-one devoid of the problematic singularities predicted at the black hole’s center. This is achieved through a modified metric incorporating a parameter that effectively ‘smears out’ the singularity, replacing it with a region of extremely high, but finite, density. Crucially, this model extends beyond the purely gravitational description of Schwarzschild by also accounting for electric charge, a characteristic frequently observed in astrophysical black hole candidates. The resulting spacetime isn’t simply a mathematical curiosity; it provides a more physically plausible representation of a black hole, allowing researchers to explore strong-field gravity scenarios without encountering the unphysical infinities inherent in singular solutions and opening avenues for testing alternative theories of gravity where such regularity might be a fundamental property of spacetime itself.

The spacetime geometry of the Charged Hayward black hole presents a unique arena for investigating the limits of general relativity and testing the validity of alternative gravitational frameworks. Traditional approaches to strong-field gravity often encounter mathematical singularities, points where physical predictions break down; this solution, by remaining regular throughout, allows physicists to model extreme gravitational environments without these problematic divergences. Consequently, detailed analysis of particle trajectories, accretion disks, and gravitational waves within this spacetime can reveal subtle deviations from Einstein’s theory, potentially illuminating the need for modified gravity. Furthermore, the Hayward metric provides a valuable testing ground for concepts arising in quantum gravity, such as the possibility of black hole remnants or modifications to the singularity structure, offering a pathway to reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics and deepen understanding of the universe’s most enigmatic objects.

The Shadow of a Singularity: Probing the Photon Sphere

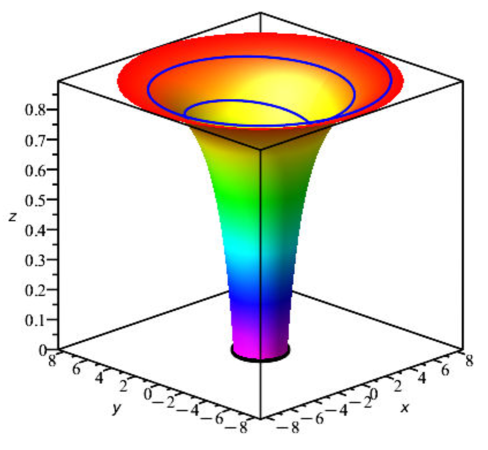

The photon sphere is a theoretical surface surrounding a black hole where gravity is strong enough to force photons to travel in orbits. These orbits are inherently unstable; any slight perturbation will cause a photon to either spiral into the black hole or escape to infinity. The radius of the photon sphere, which is 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius for a non-rotating black hole, directly determines the apparent size and shape of the black hole shadow as observed by distant observers. Because photons within the photon sphere define the boundary of the shadow, variations in the photon sphere’s radius – influenced by the black hole’s charge, spin, and surrounding spacetime geometry – translate directly into measurable changes in the black hole’s observed silhouette. The shadow is not a physical surface, but rather a region of diminished light caused by the gravitational lensing of photons near the event horizon and within the photon sphere.

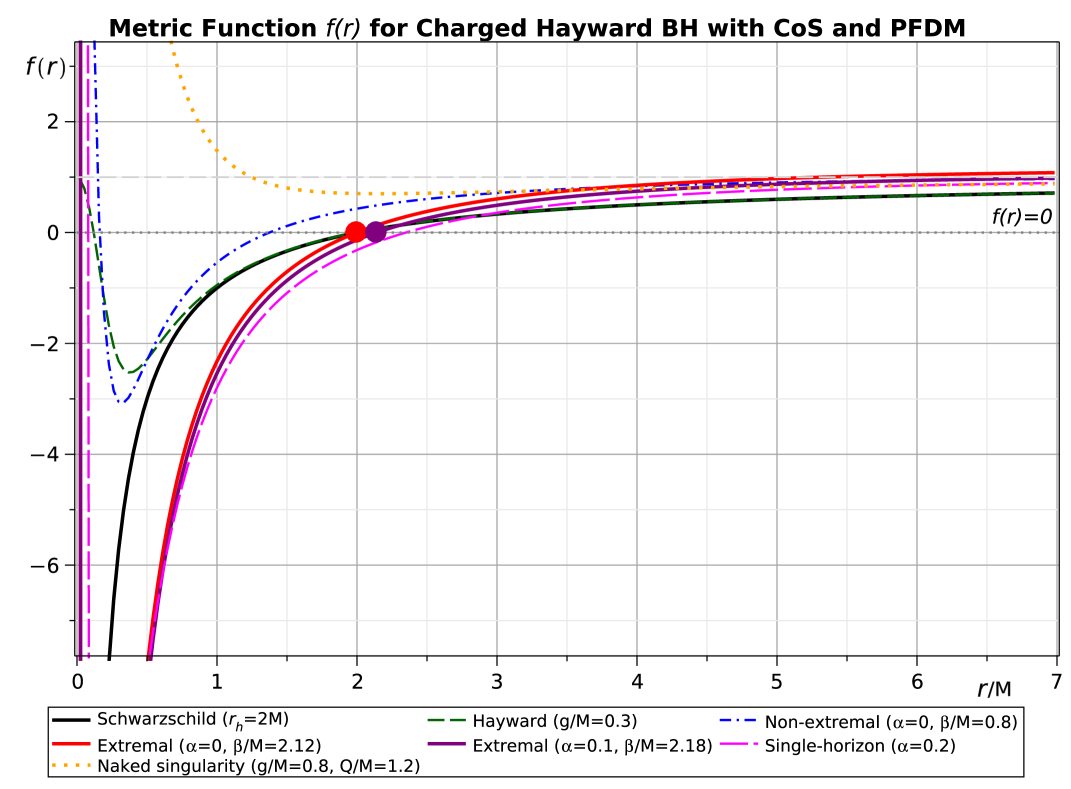

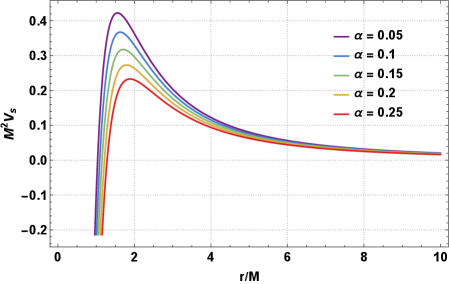

Determining photon trajectories around a Charged Hayward Black Hole necessitates the calculation of its effective potential, V_{eff}. This potential governs the motion of photons as they approach and orbit the black hole, and is derived from the black hole’s metric and the photon’s energy and angular momentum. The effective potential incorporates both the gravitational influence of the black hole and the effects of its electric charge, represented by parameters influencing the spacetime geometry. Analyzing the critical points and turning points of V_{eff} allows for the precise calculation of unstable photon orbits – those defining the photon sphere – and ultimately, the size and shape of the black hole shadow. The form of the effective potential is crucial as it dictates the allowed paths and the conditions for orbital stability.

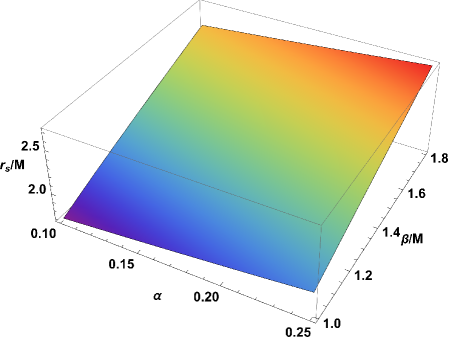

Analysis detailed in Tables 2-3 demonstrates a quantifiable relationship between the parameters α and β of the Charged Hayward Black Hole metric and the radius of its photon sphere, normalized by the black hole mass M. Specifically, increasing either α or β results in a larger photon sphere radius r_s/M. The data indicates that α exhibits a more pronounced effect on the photon sphere radius than β, with larger values of α correlating to substantially increased r_s/M values. These variations in r_s/M are directly attributable to the influence of α and β on the effective potential experienced by photons orbiting the black hole, altering the stability and size of these orbits.

Analysis presented in Figures 5 demonstrates a direct correlation between the parameters α and β of the Charged Hayward Black Hole metric and the resulting radius of the black hole shadow. Specifically, increases in either α or β consistently lead to a larger shadow radius, a measurable effect on the observed black hole silhouette. This expansion of the shadow radius is a consequence of the altered spacetime geometry induced by these parameters, impacting the unstable photon orbits that define the boundary of the shadow. The magnitude of this increase is quantifiable, offering a potential observational method for constraining the values of α and β through high-resolution astronomical imaging of black hole silhouettes.

The black hole shadow, formed by the absence of light escaping from the event horizon and influenced by strong gravitational lensing, directly reflects the underlying spacetime geometry. Analysis of the shadow’s size and shape allows for stringent tests of general relativity by comparing observed characteristics to predictions based on the Kerr metric and its modifications. Deviations from these predictions, potentially caused by effects like charge or an internal structure as modeled by the Charged Hayward Black Hole, would indicate a need to revise or extend the current understanding of gravity. Specifically, measurements of the shadow radius and asymmetry can constrain the values of parameters defining deviations from the standard Kerr spacetime, offering a unique observational probe of strong-field gravity and potential new physics.

Orbital Dynamics: Mapping the Extremes of Spacetime

The innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO) represents the closest stable path an object can maintain around a black hole in a circular orbit; orbits interior to the ISCO are inherently unstable and will lead to the object spiraling into the black hole. This radius is not a fixed value, but is dependent on the black hole’s spin and the object’s orbital angular momentum. For a non-rotating (Schwarzschild) black hole, the ISCO is located at 6M, where M is the black hole’s mass. Accretion disks, formed from infalling matter, extend down to the ISCO; material inside this radius cannot maintain a stable orbit and contributes directly to energy emission and growth of the black hole. The ISCO therefore functions as an inner boundary condition for models of accretion disk dynamics and radiative transfer.

Determination of the Innermost Stable Circular Orbit (ISCO) and the periastron precession frequency necessitates a detailed understanding of the black hole’s spacetime geometry, specifically the effective potential experienced by a test particle in orbit. The effective potential, V_{eff}, incorporates both the gravitational potential and centrifugal effects, and its form is directly derived from the Schwarzschild or Kerr metric, depending on the black hole’s spin. Calculating the ISCO involves finding the radius of the innermost stable orbit by analyzing the extrema of V_{eff}. Periastron precession frequency, representing the rate at which the point of closest approach in an elliptical orbit shifts, is then calculated from the second derivative of the effective potential and is dependent on the orbital parameters and the spacetime curvature defined by the black hole’s mass and spin.

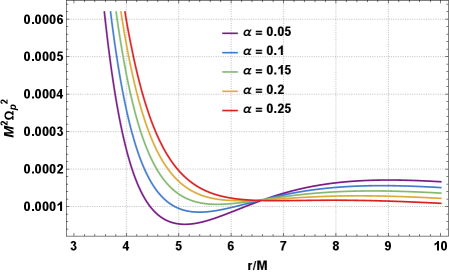

Analysis indicates a direct correlation between the parameters β/M and α and the periastron precession frequency; increases in either value result in a higher precession rate. Conversely, the vertical frequency demonstrates an inverse relationship with both β/M and α; elevating these parameters leads to a suppression of the vertical frequency. These relationships are derived from calculations of the effective potential, which dictates orbital behavior within the black hole’s spacetime. Specifically, a higher β/M, representing spin, and a larger α, related to the orbital radius, contribute to stronger relativistic effects that influence precession and vertical motion. The observed changes in frequency are quantifiable and provide data for models examining accretion disk dynamics and energy extraction mechanisms around black holes.

Orbital characteristics, specifically the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO) and periastron precession frequency, are directly linked to the efficiency of accretion processes around black holes. The ISCO defines the radius within which matter will inevitably spiral into the black hole, impacting the rate of accretion and subsequent energy release. Periastron precession, influenced by spacetime geometry and parameters like \beta/M and α, affects the stability of orbits and the manner in which matter transfers angular momentum outwards, facilitating continued accretion. Variations in precession frequency correlate with the rate of energy dissipation and the overall luminosity of the system, offering a means to study energy extraction mechanisms such as the Blandford-Znajek process and the efficiency of different accretion disk models.

Whispers of Spacetime: Quasinormal Modes and Perturbations

Scalar perturbations represent deviations from a spacetime geometry, mathematically described by scalar fields that exhibit changes in amplitude over time. These perturbations, when applied to a black hole, do not simply reflect off its event horizon; instead, they propagate into the strong gravitational field and are fundamentally altered. The resulting distortion of spacetime, measured through the evolution of the scalar field, directly characterizes the black hole’s response to external disturbances. Analysis of these perturbations provides information about the black hole’s intrinsic properties, such as mass and spin, and how it dissipates energy when subjected to external forces. The specific frequencies at which these perturbations decay-the quasinormal modes-are unique to the black hole and act as a “fingerprint” of its characteristics, distinct from responses observed in other compact objects.

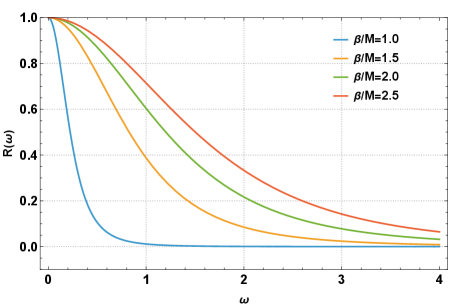

Solving for spacetime perturbations requires analyzing the Klein-Gordon equation, a relativistic wave equation, applied to the scalar field describing the disturbance. Direct solutions are often intractable, necessitating the WKB (Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin) approximation, an asymptotic method used to approximate solutions to differential equations. This approximation allows for the determination of quasinormal modes – characteristic frequencies at which the black hole “rings” after a perturbation. These modes are not purely oscillatory; they exhibit decaying exponential behavior, represented mathematically as \omega = \omega_0 - i\Gamma , where \omega_0 is the real frequency and Γ represents the damping rate. The complex frequencies of these quasinormal modes uniquely characterize the black hole’s response to external disturbances and depend on the black hole’s mass and spin.

Observations of accreting black holes frequently reveal quasi-periodic oscillations (QPOs) in their X-ray emissions. These oscillations, which are not strictly periodic but decay over time, are strongly correlated with the quasinormal modes (QNMs) of the black hole spacetime. Specifically, the frequencies of observed QPOs often match the real part of the complex frequencies calculated for the black hole’s QNMs, suggesting that the perturbations causing these oscillations are governed by the black hole’s inherent response to external disturbances. The decay time of the QPOs aligns with the imaginary part of the QNM frequencies, representing the rate at which these oscillations are damped due to gravitational wave emission and other dissipation mechanisms. Analysis of these QPO frequencies provides a method for indirectly measuring the mass and spin of the black hole, as these parameters directly influence the QNM spectrum ω.

Beyond Einstein: New Physics and the Black Hole Landscape

The Charged Hayward black hole presents a compelling modification to the standard black hole model, notably allowing for the incorporation of complex physical phenomena like perfect fluid dark matter. Unlike the simpler Schwarzschild or Kerr solutions, the Hayward metric introduces a parameter that effectively prevents the singularity at the black hole’s center, replacing it with a regular, though highly dense, region. This characteristic is crucial because it permits the self-consistent inclusion of matter with negative pressure – a defining trait of dark matter – within the black hole’s structure. Researchers have demonstrated that by treating dark matter as a perfect fluid and embedding it within the Charged Hayward spacetime, it becomes possible to model black holes surrounded by, or even composed of, this elusive substance. The resulting solutions yield alterations to the black hole’s event horizon and ergosphere, influencing gravitational lensing effects and potentially offering a pathway to indirectly detect and characterize dark matter through observations of its gravitational footprint. The R^2 curvature term inherent in the Hayward metric proves vital in accommodating these exotic matter contributions without violating the fundamental principles of general relativity.

The very fabric of spacetime around a black hole isn’t immutable; it’s demonstrably shaped by the presence of exotic matter. Recent investigations demonstrate that incorporating parameters representing ‘string clouds’ – hypothetical formations of cosmic strings – profoundly alters the geometry surrounding a black hole. These alterations aren’t merely theoretical; they directly influence observable phenomena, most notably the black hole shadow. The shadow, a dark region caused by the black hole bending light, isn’t a simple circular shape, but rather exhibits distortions and asymmetries dependent on the density and configuration of these string clouds. By meticulously analyzing the shape and intensity profile of the black hole shadow – a feat increasingly achievable with instruments like the Event Horizon Telescope – scientists can begin to constrain the parameters of these string clouds, potentially revealing insights into the fundamental nature of gravity and the existence of previously unknown cosmic structures. The size and form of the shadow, therefore, serves as a crucial observational window into the interplay between gravity and these unusual, yet theoretically plausible, components of the universe.

The exploration of modified black hole models, incorporating elements like dark matter and string clouds, presents a unique avenue for rigorously testing the boundaries of general relativity. By examining how these additions alter established parameters – such as the size and shape of the black hole shadow, or the trajectories of photons and particles in strong gravitational fields – scientists can begin to differentiate between predictions made by Einstein’s theory and those arising from alternative gravitational frameworks. This approach isn’t merely theoretical; future astronomical observations, particularly those employing very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) to image black hole silhouettes, hold the potential to either validate or refute these modifications, offering crucial insights into the fundamental nature of gravity and the exotic matter that may permeate the universe. The interplay between black holes, as both gravitational anchors and potential probes of new physics, thus positions them at the forefront of efforts to unravel the mysteries beyond our current understanding.

The study of the Hayward black hole, interwoven with dark matter and string cloud environments, reveals a compelling resonance with ancient wisdom. As Confucius stated, “Study the past if you would define the future.” This research, meticulously examining the black hole’s shadow, geodesics, and quasinormal spectrum, echoes this sentiment. The pursuit of understanding these complex systems isn’t merely about quantifying gravitational forces; it’s about discerning patterns within chaos. Just as a skilled artisan refines form to reveal function, this investigation seeks to identify subtle observational signatures-the ‘shadow’ and spectral lines-that differentiate this black hole from its simpler counterparts. Beauty scales, clutter does not, and a refined theoretical model, like a carefully composed design, offers clarity amidst complexity.

Beyond the Horizon

The exploration of charged Hayward black holes, nestled within dark matter halos and threaded by string clouds, reveals not a destination, but an ever-receding horizon of inquiry. The present work, while illuminating the interplay between these exotic components and observable signatures like photon spheres and quasinormal modes, subtly underscores how little is truly understood. The elegance of general relativity, it seems, demands a price: an increasing complexity when attempting to reconcile theory with the universe’s evident messiness.

Future investigations must confront the limitations inherent in assuming spherical symmetry, or static backgrounds. A dynamic universe necessitates a dynamic black hole-one that accretes, spins, and interacts with its surroundings in a manner far more nuanced than current models allow. Furthermore, the coupling constants governing the strength of the string cloud and the density profile of the dark matter remain largely unconstrained. These parameters, treated as adjustable knobs in the present analysis, demand rigorous connection to fundamental physics.

Perhaps the most compelling path forward lies in embracing the inherent ambiguity. The search for definitive observational evidence-a unique spectral fingerprint, a deviation from the expected shadow shape-may prove futile. Instead, the focus should shift toward statistical inference, seeking subtle correlations between these theoretical features and the growing wealth of astronomical data. The universe rarely shouts its secrets; it whispers them in the noise.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.02621.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- Gigi Hadid, Bradley Cooper Share Their Confidence Tips in Rare Video

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 7 Best Clone Troopers in Star Wars, Ranked By Impact

2026-02-04 20:12