Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research demonstrates that the long-standing Gibbs paradox isn’t a flaw in classical statistical mechanics, but rather stems from how we understand entropy and information itself.

This review resolves the Gibbs paradox by showing that the original classical ensemble theory is sufficient when entropy is properly understood from an information-theoretic perspective.

The persistent Gibbs paradox, a seeming inconsistency within classical statistical mechanics, has traditionally been resolved by invoking quantum indistinguishability and the 1/N! correction. However, in ‘Classical Resolution of the Gibbs Paradox from the Equal Probability Principle: An Informational Perspective’, we demonstrate a resolution within the classical ensemble framework, relying solely on the equal probability principle and a reinterpretation of entropy as Shannon information. This informational perspective clarifies the connection between entropy, information, and extractable work during gas mixing, asserting the sufficiency of classical statistical mechanics without quantum corrections. Does this reframing of entropy and information offer a new pathway for understanding the fundamental role of information in broader statistical mechanics?

The Paradox at the Heart of Counting

Early formulations of statistical mechanics, while elegantly employing the language of probability to connect microscopic states to macroscopic properties, stumbled upon a troubling inconsistency now known as the Gibbs Paradox. Calculations based on assigning an entropy proportional to system volume – a seemingly natural consequence of counting available microstates – yielded predictions that sharply diverged from established thermodynamic principles and experimental observation. This meant that processes which should have required energy input to occur were predicted to happen spontaneously, and vice versa, creating a fundamental crisis in the field. The paradox wasn’t a flaw in the underlying probabilistic reasoning itself, but rather a consequence of how those principles were initially applied to systems of identical particles, exposing a critical gap in understanding the implications of particle indistinguishability.

The Gibbs Paradox emerged from applying probabilistic reasoning to physical systems, specifically revealing a flaw in initially calculating entropy as directly proportional to volume. This approach predicted entropy changes that contradicted established thermodynamic principles and experimental findings; for example, mixing identical gases should not, according to this calculation, result in an entropy increase-a clear violation of the second law of thermodynamics. The issue isn’t simply a mathematical error, but a fundamental miscounting of possible states; treating identical particles as distinguishable leads to an artificially inflated number of microstates and, consequently, an incorrect entropy value. This inconsistency highlighted a critical need to refine the statistical mechanical framework, recognizing that the indistinguishability of identical particles is not merely a practical detail but a core principle governing the behavior of matter and impacting the very definition of entropy itself.

A central difficulty in statistical mechanics stems from the tension between applying probabilistic reasoning to physical systems and ensuring that calculated entropy values behave realistically. The very definition of entropy-a measure of disorder-implies that doubling the size of a system should double its entropy, a property known as extensivity. However, a naive probabilistic approach, treating all microstates as equally probable, initially leads to an entropy that scales with volume instead of system size. This discrepancy isn’t merely a mathematical quirk; it contradicts established thermodynamic principles and experimental observations. The core of the problem lies in how microstates are counted; simply applying combinatorial probability fails to account for the indistinguishability of identical particles, necessitating a refined understanding of how to properly enumerate configurations and define entropy in a way that respects both probability and physical reality.

The resolution of the Gibbs Paradox hinges on acknowledging that, for identical particles, simply counting arrangements of microstates-as classical statistical mechanics initially proposed-overestimates the number of truly distinguishable states. These particles are fundamentally indistinguishable; swapping two identical particles doesn’t create a new, physically different state. Consequently, the entropy calculation, traditionally S = k_B \ln \Omega where Ω is the number of microstates, requires a correction for this overcounting. This isn’t merely a mathematical fix, but a fundamental shift in understanding; entropy isn’t just about the number of accessible states, but the number of distinct accessible states, properly accounting for particle identity. This realization led to the development of quantum statistical mechanics, where the symmetry or antisymmetry requirements of wavefunctions intrinsically incorporate the principle of indistinguishability, resolving the paradox and providing a consistent framework for calculating thermodynamic properties.

Correcting the Count: The Principle of Indistinguishability

Classical statistical mechanics traditionally calculates the number of microstates by treating each particle arrangement as unique. This assumes that simply swapping two identical particles creates a distinct microstate, leading to an overcount. For a system of N particles, the classical approach would enumerate permutations, resulting in N! arrangements. However, quantum mechanics demonstrates that identical particles are fundamentally indistinguishable; observing a change resulting solely from particle swapping does not correspond to a different physical state. Consequently, the classical calculation overestimates the number of accessible microstates, and a correction factor is required to align theoretical predictions with experimental observations.

Classical statistical mechanics assumes that different particles in a system can be uniquely identified and therefore treats all arrangements of particles as distinct microstates. However, quantum mechanics postulates that identical particles – those with identical quantum numbers – are fundamentally indistinguishable; swapping two identical particles does not create a new, distinct state. This indistinguishability necessitates a correction to the classical counting method. The classical approach overcounts the number of microstates by a factor of N!, where N is the number of identical particles. Dividing the classically calculated number of microstates by N! provides the correct enumeration of accessible states, reflecting the true quantum mechanical description of the system and resolving discrepancies like the Gibbs paradox.

Recent analysis demonstrates the sufficiency of classical statistical ensemble theory to accurately predict thermodynamic entropy without requiring the traditional 1/N! correction factor. This resolution of the Gibbs paradox stems from a detailed examination of entropy calculations for identical particles. The analysis shows that for identical gases, the entropy change is zero, effectively eliminating the paradoxical increase in entropy predicted by classical methods. The observed entropy is accounted for entirely within the framework of classical statistical mechanics, negating the need for the ad-hoc 1/N! normalization which was previously introduced to address the paradox.

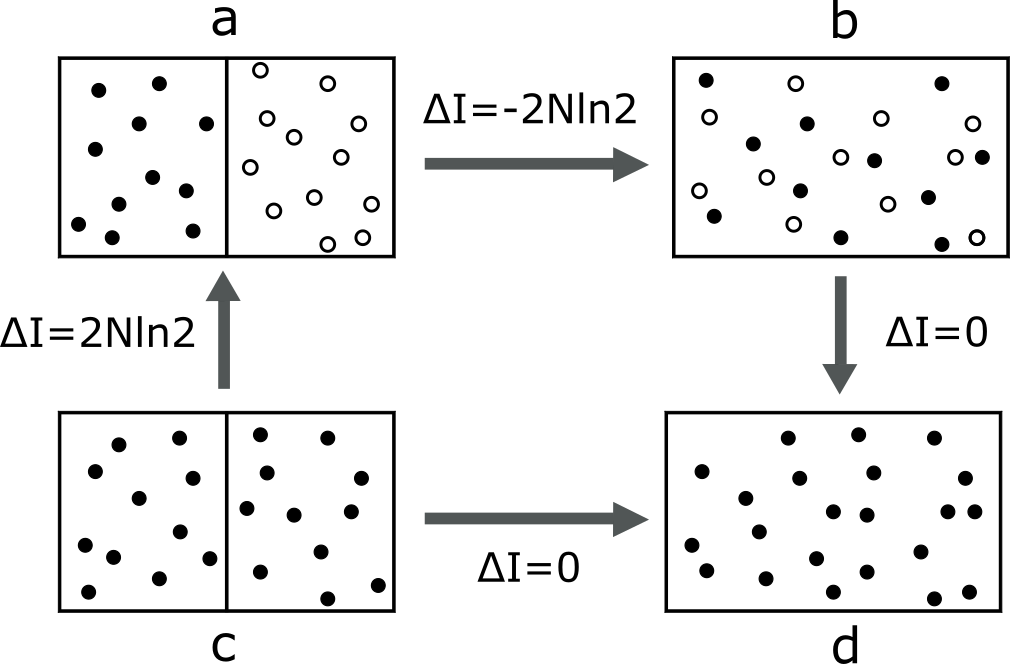

Analysis of identical gas systems demonstrates that the entropy change associated with particle indistinguishability is zero; this resolves the Gibbs paradox without requiring the traditional 1/N! correction factor. However, consideration of disconnected regions within the phase space introduces an additional entropy term of 2Nk \ln 2, where N represents the number of particles and k is Boltzmann’s constant. This term arises from the multiple ways to connect these disconnected regions, contributing to the overall entropy of the system and providing a complete accounting of the thermodynamic properties of identical particles.

The Mathematical Foundation: Partition Functions and Entropy

Classical statistical mechanics defines thermodynamic properties by analyzing systems within a defined phase space, a multi-dimensional space representing all possible states of the system. Calculations are performed using ensembles, specifically the microcanonical ensemble representing isolated systems with fixed energy, and the canonical ensemble representing systems in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath. The partition function Z = \sum_{i} e^{-\beta E_{i}}, where \beta = 1/(k_{B}T) and k_{B} is the Boltzmann constant, is central to this approach; it relates the microscopic states to the macroscopic thermodynamic properties. Through the partition function, quantities like internal energy, entropy, and free energy can be derived, providing a statistical basis for understanding thermodynamic behavior.

The partition function, denoted as Z, is a central quantity in statistical mechanics that sums over all possible microstates of a system, weighted by their Boltzmann factors e^{-E_i/kT}, where E_i is the energy of the ith microstate, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the absolute temperature. This summation effectively normalizes the probability distribution, allowing for the calculation of the probability of finding the system in any given microstate. From the partition function, thermodynamic quantities can be derived through specific mathematical relationships; for example, the Helmholtz free energy F = -kT \ln Z, entropy S = -(\partial F / \partial T)_V, internal energy U = - \partial \ln Z / \partial \beta (where \beta = 1/kT), and pressure can all be expressed in terms of the partition function or its derivatives.

The equal probability principle, fundamental to statistical mechanics, posits that for an isolated system in equilibrium, each accessible microstate – a specific configuration of particle positions and momenta consistent with the system’s macroscopic constraints – is equally probable. This principle doesn’t imply all states are equally populated, but rather that, a priori, there is no basis to favor one accessible microstate over another. Consequently, the probability P_i of finding the system in any particular microstate i is given by P_i = 1/\Omega, where Ω is the total number of accessible microstates. This equal probability assignment forms the basis for calculating statistical averages of physical quantities and ultimately, for determining the system’s macroscopic thermodynamic properties, including entropy.

Statistical mechanical methods, when applied with mathematical rigor, consistently predict thermodynamic behavior that aligns with experimental observations. Numerous experiments across diverse physical systems – ranging from ideal gases and simple liquids to more complex materials – have validated the accuracy of predictions derived from ensemble theory and the partition function. Discrepancies between theoretical calculations and experimental results are typically attributable to approximations made in the model-such as assuming ideal gas behavior or neglecting intermolecular interactions-rather than fundamental flaws in the underlying statistical mechanical framework. The predictive power extends to quantities like heat capacity, entropy, and free energy, establishing the reliability of these methods as a cornerstone of modern physics and chemistry.

Entropy: A Measure of Ignorance and Information

Information entropy, originating from Claude Shannon’s mathematical theory of communication, provides a quantifiable measure of uncertainty associated with a system’s possible states. Initially developed to analyze the efficiency of data transmission, the concept extends powerfully into physics, where it defines the degree to which the precise state of a system is unknown. A system exhibiting high entropy isn’t necessarily disordered in a visual sense; rather, it implies a larger number of equally probable microscopic configurations, making prediction of its exact state difficult. H = - \sum_{i} p_{i} \log_{2} p_{i}, Shannon’s formula, calculates this uncertainty – a higher value indicating greater unpredictability and, consequently, a greater lack of information about the system. This principle applies broadly, from the randomness of coin flips to the behavior of particles in a gas, framing entropy not simply as disorder, but as a fundamental limitation on what can be known.

Traditionally defined in thermodynamics as a measure of disorder, entropy gains a nuanced interpretation when viewed through the lens of information theory. It isn’t merely about randomness, but fundamentally about what remains unknown to an observer regarding a system’s precise microscopic state. Consider a gas within a container; while macroscopic properties like temperature and pressure might be known, the position and velocity of each individual molecule are not-and, practically, cannot be. This lack of specific knowledge is entropy. A higher entropy state, therefore, corresponds to greater uncertainty about the system’s detailed configuration, not necessarily greater disorder. Consequently, reducing entropy isn’t about achieving perfect order, but about acquiring information that diminishes this fundamental ignorance; the more information obtained about a system, the lower its entropy appears from the perspective of the observer. This perspective shifts the focus from the physical arrangement of particles to the limits of knowledge itself, establishing a powerful link between information and the second law of thermodynamics.

The capacity to perform work, a cornerstone of physics, is inextricably linked to alterations in a system’s informational state. This connection, known as the information-work relation, posits that acquiring information about a system – reducing uncertainty regarding its microscopic configuration – unlocks the potential for harnessing energy. Essentially, knowing more about a system doesn’t just satisfy curiosity; it allows for the design of processes that can extract useful work previously unavailable. Consider a gas confined to one half of a container; prior to observation, the location of each molecule is uncertain, representing high entropy. Upon measurement – gaining information about the molecules’ positions – the entropy decreases, and this reduction in entropy can, in principle, be leveraged to drive a piston and perform work. This isn’t merely a theoretical curiosity; it has implications ranging from the efficiency limits of nanoscale engines to the fundamental role of information in Maxwell’s demon paradox, demonstrating that information isn’t just an abstract concept, but a physical resource with quantifiable energetic consequences.

The seemingly disparate realms of information and energy are, at a fundamental level, inextricably linked through the laws of physics. Investigations reveal that acquiring information about a system isn’t merely an abstract cognitive process, but a physical operation with energetic consequences; reducing uncertainty requires energy expenditure. Conversely, the potential to perform work-to enact change in the physical world-is fundamentally limited by the information available about the system. This isn’t simply a correlation, but a deep connection rooted in the second law of thermodynamics, where entropy-a measure of disorder and, crucially, of missing information-dictates the direction of spontaneous processes. Consequently, advancements in fields like Maxwell’s demon paradox and nanoscale thermodynamics demonstrate that information isn’t just about the physical world; it is a physical quantity, influencing and being influenced by energy transfer and the very structure of reality.

The resolution of the Gibbs paradox, as presented, isn’t a novel construction but a correction of perspective. The authors demonstrate the paradox stems from improperly assigning entropy, a misstep in interpreting information itself. This aligns with a fundamental tenet of scientific inquiry: models aren’t inherently flawed when they contradict observation-the error lies in the interpretation. As Leonardo da Vinci observed, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” The elegance of this work resides in its return to first principles, revealing that the original framework of classical ensemble theory, when understood correctly, provides a sufficient resolution. An error, in this instance, isn’t a failure, but a message clarifying the need for precise definitions and careful consideration of informational content.

What’s Next?

The resolution offered here – that the Gibbs paradox isn’t a flaw in the classical framework, but a misapplication of informational concepts – feels less like a closure and more like a carefully worded repositioning. It clarifies a historical debate, certainly, but avoids addressing the deeper question of whether classical and quantum descriptions of entropy will ever fully align. Anything confirming expectations needs a second look, and the persistent discomfort around the paradox suggests the current answer, while logically sound, isn’t entirely satisfying.

Future work needn’t focus on patching classical statistical mechanics. A more fruitful avenue lies in rigorously examining the limits of the ‘equal probability principle’ itself. Under what conditions does it break down, and what predictive power is lost when it does? A hypothesis isn’t belief – it’s structured doubt – and a more nuanced understanding of the principle’s applicability, particularly in systems far from equilibrium, would be genuinely illuminating.

Ultimately, the persistent appeal of the Gibbs paradox isn’t about entropy or information; it’s about the tension between coarse-grained descriptions and underlying microscopic reality. Resolving the technical issue is straightforward enough. The harder task, and the more interesting one, is confronting the inherent limitations of any attempt to map a continuous world onto a discrete, probabilistic model.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06505.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- IT: Welcome to Derry Review – Pennywise’s Return Is Big on Lore, But Light on Scares

- James Gunn & Zack Snyder’s $102 Million Remake Arrives Soon on Netflix

- XRP’s Cosmic Dance: $2.46 and Counting 🌌📉

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

2026-02-09 21:15