Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that the emergence of wavefront dislocations in bilayer honeycomb lattices is governed by the material’s intrinsic pseudospin texture, challenging previous assumptions about topological charge.

Wavefront dislocations in bilayer honeycomb lattices are determined by pseudospin texture rather than topological charge or vorticity of band touchings.

The definitive interpretation of wavefront dislocations (WDs) as direct signatures of Berry phase in two-dimensional materials has remained a central tenet in understanding quantum phenomena within these systems. This research, presented in ‘Wavefront-Dislocation Evolution via Quadratic Band Touching Annihilation’, investigates the origins of WDs observed in quasiparticle interference experiments, disentangling the roles of topological charge and pseudospin texture. We demonstrate that WD evolution is governed exclusively by changes in the underlying pseudospin winding, remaining insensitive to the topological charge of band touchings-effectively revealing that WDs map wavefunction pseudospin texture rather than topological charge. Could this finding enable the engineering of novel quantum devices based on controlled pseudospin manipulation and observable WD evolution?

Emergent Order: Unveiling the Symmetry of Materials

The quest for designing materials with tailored properties fundamentally relies on understanding the symmetries inherent within their atomic structure. These symmetries – rotational, translational, and others – dictate the allowed electronic states and, consequently, the material’s electrical conductivity, optical response, and magnetic behavior. Manipulating these symmetries, even subtly, can unlock entirely new functionalities. For instance, breaking a symmetry can create localized electronic states responsible for superconductivity, while preserving certain symmetries can lead to topologically protected states robust against imperfections. Researchers increasingly leverage this principle, employing computational models and experimental techniques to predict and realize materials with desired characteristics, ranging from high-efficiency solar cells to quantum computing components. The ability to engineer symmetry within materials represents a powerful paradigm for materials discovery and innovation.

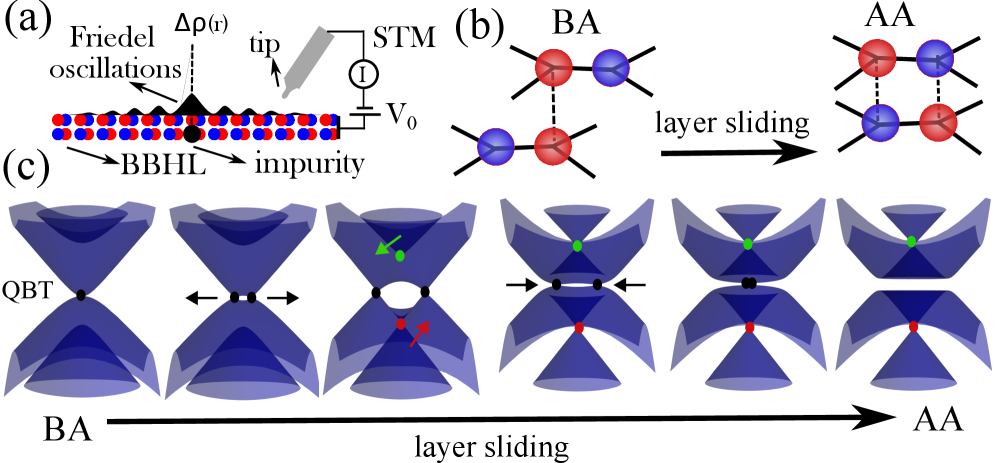

The Bilayer Binary Honeycomb Lattice (BBHL) model emerges as a powerful theoretical construct for investigating unconventional electronic behavior in materials. This model, representing a stacked arrangement of two honeycomb lattices with alternating atomic species, allows physicists to systematically explore the emergence of Quadratic\,Band\,Touchings (QBTs). Unlike typical linear band crossings, QBTs exhibit a unique k^2 dependence near the touching points, leading to highly unusual electron dynamics and transport properties. The BBHL’s tunability-achieved by manipulating interlayer coupling and atomic arrangements-provides a versatile platform to not only observe QBTs but also to engineer materials with tailored electronic responses, potentially unlocking novel functionalities in areas like low-dissipation electronics and quantum computing. It offers a simplified, yet insightful, representation of complex systems, bridging the gap between theoretical predictions and the design of future materials.

Quadratic Band Touchings (QBTs) within the Bilayer Binary Honeycomb Lattice model aren’t merely points of band crossing; they fundamentally reshape how electrons behave as if possessing an internal, emergent degree of freedom known as pseudospin. Unlike conventional spin, this pseudospin arises from the unique symmetry of the lattice and dictates the electron’s response to external stimuli. The resulting pseudospin textures, which describe the orientation of this emergent property across the material, aren’t uniform but instead form complex patterns-vortices, skyrmions, and other topological configurations. These textures dramatically influence electron transport, potentially leading to phenomena like protected edge states and enhanced conductivity, and offer a pathway towards manipulating electronic properties with unprecedented control. Understanding and harnessing these pseudospin textures represents a significant step in designing materials with tailored functionalities.

Revealing Electronic Structure: The Language of Observation

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy with Spectroscopy (STM-STS) measures the local density of states (LDOS) by utilizing the tunneling current between a sharp metallic tip and a conductive sample. A bias voltage is applied between the tip and sample, and the resulting current is highly sensitive to the available electronic states at the energy corresponding to the bias voltage and spatial location under the tip. By rastering the tip across the sample surface and recording the current as a function of position and bias, a map of the LDOS can be constructed, effectively visualizing the distribution of electronic states at the atomic scale. This technique is applicable to a wide range of materials, including surfaces, interfaces, and nanostructures, and provides insights into their electronic properties.

Friedel Oscillations, observed via Scanning Tunneling Microscopy with Spectroscopy (STM-STS), manifest as spatially periodic modulations in the local density of states (LDOS) surrounding an impurity or scattering center. These oscillations arise from the interference of scattered electronic waves, with the wavelength of the oscillations determined by the Fermi wavevector k_F and the scattering potential. Specifically, the period of the Friedel oscillations is given by \frac{2\pi}{2k_F}, resulting in a characteristic decay of amplitude with distance from the impurity. STM-STS directly maps these modulations by measuring the spatial variation of the LDOS at a constant energy, providing a real-space visualization of the interference pattern and confirming the presence of scattering events.

Fourier Transform Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (FT-STS) extends the capabilities of conventional STS by analyzing the spatial frequency components of the measured local density of states (LDOS). This is achieved by performing a two-dimensional Fourier transform on the STS data, converting real-space LDOS images into momentum-space maps S(\mathbf{k}). These maps directly reveal the wavevector \mathbf{k} of scattering events occurring within the material. Specifically, peaks in the S(\mathbf{k}) spectrum correspond to dominant scattering vectors, providing information about the underlying electronic band structure, Fermi surface topology, and the presence of any periodic modulations or defects that contribute to scattering.

Fourier Transform Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (FT-STS) enables the direct visualization of wavefront dislocations in the local density of states. These dislocations, appearing as phase singularities in the FT-STS data, are topological defects in the electronic wavefunction. Their presence is directly linked to the pseudospin texture of the material, specifically the spatial variations in the direction of spin polarization. The number and chirality of these dislocations are determined by the topology of the pseudospin texture; therefore, mapping their distribution via FT-STS provides a method for characterizing the underlying spin configuration and identifying topological features in the electronic structure, such as Dirac cones or Weyl points.

Beyond Topology: The Primacy of Pseudospin

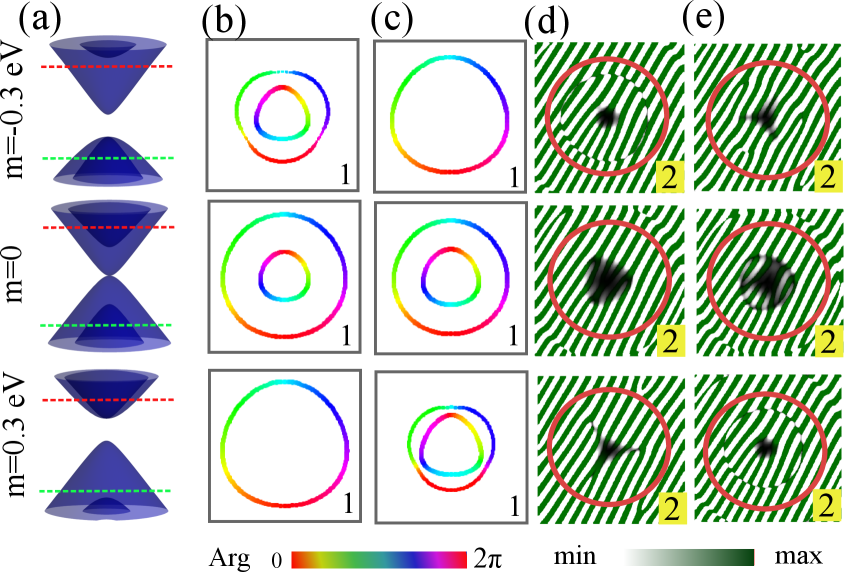

Conventional models posit a direct relationship between wavefront dislocations (WDs) and topological charge, particularly in systems exhibiting band touchings; however, our investigations into Bi-Bi-HL lattices (BBHLs) reveal this connection is not the dominant mechanism. While WDs are frequently associated with non-zero topological charge arising from band structure features, our data demonstrates that the observed dislocations in BBHLs are instead fundamentally determined by the local pseudospin texture within the lattice. This decoupling is evidenced by the persistence of a WD charge of 2 even after the removal of band touching points via sublattice potential application, indicating that the observed interference patterns are not driven by topological invariants but rather by the configuration of the pseudospin field.

Wavefront dislocations observed within the BBHL (Bi-Bi-HL) lattice are not a consequence of topological charge, but are directly determined by the complex spatial arrangement of the pseudospin texture. This texture, representing the spin polarization of the electrons within the material, exhibits intricate winding patterns that directly correlate with the locations and characteristics of the observed dislocations. Specifically, the pseudospin’s directional preference and its variation across the lattice create localized phase shifts in the electronic wavefunction, manifesting as these dislocations in interference patterns. The pseudospin texture, therefore, acts as the primary organizing principle governing the formation and arrangement of these dislocations, independent of any underlying topological invariants related to band touching points.

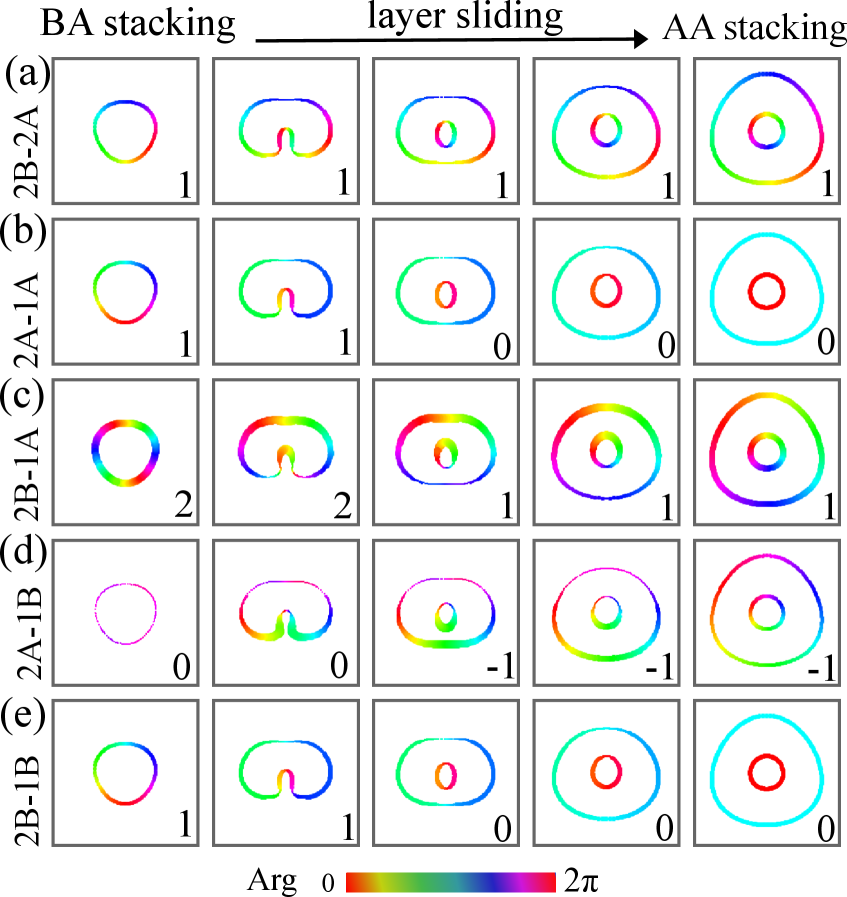

Manipulation of the pseudospin texture within BBHL lattices allows for direct control of Wavefront Dislocations through two primary methods: Layer Sliding and Sublattice Potential application. Layer Sliding involves physically shifting adjacent layers of the lattice, inducing a re-arrangement of the pseudospin configuration and consequently altering the positions of WDs. Similarly, the application of a Sublattice Potential selectively modifies the energy of specific atoms within the lattice, effectively reshaping the pseudospin texture and providing a means to engineer the WDs. These techniques demonstrate that WDs are not fixed by inherent topological properties but are instead responsive to external control of the underlying pseudospin configuration.

Experimental results indicate the Wavefront Dislocation (WD) charge consistently remains at a value of 2, irrespective of the removal of the Quadratic Band Touching (QBT) point through the application of a sublattice potential. This observation establishes the independence of WD charge from band-touching vorticity, a characteristic previously understood to be a primary determinant of topological charge. The persistence of a WD charge of 2 following QBT removal demonstrates that the observed dislocations are not solely reliant on the band structure’s topological properties, but originate from a separate mechanism governing their formation and stability.

Experimental observation confirms that the pseudospin winding within intralayer channels remains consistent during both layer sliding and sublattice tuning manipulations. This stability is significant because it directly correlates with the presence and behavior of Wavefront Dislocations (WDs). The persistence of the pseudospin winding, even as external parameters are altered, provides strong evidence that the WDs are not a consequence of topological charge, but are fundamentally dictated by the underlying pseudospin texture of the material. These findings demonstrate a direct link between the pseudospin configuration and the resulting interference patterns observed in the system.

Experimental manipulation of Bidirectional Beam Helical Light (BBHL) lattices confirms that observed interference patterns are governed by the pseudospin texture, independent of topological charge. Specifically, alterations to the pseudospin texture via layer sliding or application of sublattice potentials directly correlate with changes in Wavefront Dislocation (WD) positions, while the WD charge consistently remains at 2, even when the band-touching point-typically associated with vorticity and topological charge-is removed. This decoupling demonstrates that the pseudospin winding within the BBHL lattice, rather than any inherent topological property, is the primary determinant of the observed interference phenomena and the location of WDs.

Towards Materials-by-Design: Harnessing Pseudospin for Innovation

To move beyond purely theoretical predictions, researchers engineered a physical system capable of demonstrating the Berry-Bloch-Holstein (BBH) physics – specifically, a metamaterial structure. These artificial materials, meticulously designed with subwavelength features, allowed for the tangible realization of the previously modeled phenomena. By fabricating these structures, scientists could directly observe and characterize the interplay of spin and charge, validating the theoretical framework. This implementation not only confirms the BBH model but also establishes a platform for exploring and manipulating pseudospin textures in a controlled environment, paving the way for potential applications in advanced materials science and novel device technologies.

The transition from theoretical prediction to physical demonstration is a cornerstone of scientific advancement, and recent work has successfully manifested the predicted phenomena through the fabrication of metamaterial structures. These engineered materials, designed with subwavelength features, serve not merely as illustrations of complex physics, but as platforms for rigorous experimental verification. By constructing physical analogs of the modeled systems, researchers can directly observe and quantify the behavior of pseudospin textures and the effects of broken Time-Reversal Symmetry. This tangible realization confirms the validity of the underlying theoretical framework and unlocks opportunities for further investigation into the manipulation of light and matter at the nanoscale, paving the way for novel device applications and a deeper understanding of fundamental physical principles.

The manipulation of magnetic interactions presents a compelling route toward engineering sophisticated pseudospin textures within materials. By deliberately disrupting Time-Reversal Symmetry – a fundamental principle stating that the laws of physics remain consistent regardless of the direction of time – researchers can move beyond simple, static spin arrangements. This breaking of symmetry encourages the formation of more intricate patterns, like skyrmions and merons, which exhibit unique topological properties. These complex textures aren’t merely academic curiosities; they directly influence a material’s electronic and optical behavior, potentially enabling novel device functionalities and opening doors to advanced technologies centered around spintronics and photonics. The ability to precisely control these textures through magnetic fields or material design represents a significant step toward realizing materials with tailored and programmable properties.

The ability to manipulate pseudospin textures through broken Time-Reversal Symmetry presents a significant leap towards materials-by-design. Researchers anticipate crafting materials where electronic and optical characteristics are not merely inherent but intentionally engineered at a fundamental level. This control extends to phenomena like light absorption, reflection, and refraction, potentially leading to advancements in areas such as high-efficiency solar cells, novel optical sensors, and even cloaking technologies. By carefully tailoring the magnetic interactions within these metamaterials, it becomes possible to dictate how electrons and photons behave, effectively programming matter to respond to external stimuli in pre-defined ways and unlocking a new era of functional materials.

The study illuminates a fascinating principle: order doesn’t necessitate a guiding hand. Rather than being dictated by overarching topological charge, the wavefront dislocations within the bilayer honeycomb lattice arise from the material’s intrinsic pseudospin texture. This bottom-up emergence of structure mirrors a natural tendency toward stability, suggesting that control is often an illusion. As Galileo Galilei observed, “You cannot teach a universe how to operate.” The research subtly demonstrates this, revealing that complex phenomena, like the evolution of wavefront dislocations, originate from localized interactions and inherent material properties, not from imposed external directives.

Where Do the Ripples Lead?

The insistence on linking macroscopic phenomena – in this case, the emergence of wavefront dislocations – to microscopic origins often feels… presumptive. This work subtly shifts that burden, demonstrating that the arrangement of states, the pseudospin texture, dictates dislocation patterns more readily than any inherent topological charge. Robustness emerges from this arrangement; it cannot be designed. The focus, then, isn’t on creating topological features, but on understanding how naturally occurring textures shape observable outcomes.

Future investigations will likely move beyond simply identifying correlations between pseudospin texture and dislocation behavior. The true challenge lies in predicting the emergence of complex wavefront patterns in systems with more disordered or heterogeneous textures. Attempts to engineer specific textures for precise control will almost certainly prove frustrating; the system will find its own equilibrium. System structure is stronger than individual control.

It remains to be seen whether this principle extends to other quasiparticle interference phenomena, or even to entirely different physical systems. Perhaps the real lesson isn’t about band touching or bilayer lattices, but about the limitations of seeking top-down explanations for bottom-up processes. The ripples spread, and their destinations are not predetermined.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06397.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- Pokémon Legends: Z-A’s Mega Dimension Offers Level 100+ Threats, Launches on December 10th for $30

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Ben Napier & Erin Napier Share Surprising Birthday Rule for Their Kids

- James Gunn & Zack Snyder’s $102 Million Remake Arrives Soon on Netflix

2026-02-10 02:18