Author: Denis Avetisyan

Recent advancements leverage the unique properties of Rydberg atoms to explore the fascinating realm of non-Hermitian physics and its implications for quantum technologies.

This review details the utilization of Rydberg atom systems as a platform for observing exceptional points, topological phases, and enhanced quantum sensing through non-Hermitian approaches.

While traditional quantum systems are governed by Hermitian Hamiltonians, emerging research explores the unique phenomena arising from their non-Hermitian counterparts. This review, ‘Non-Hermitian physics in the many-body system of Rydberg atoms’, details recent advances in utilizing highly controllable Rydberg atom arrays as a versatile platform to investigate these non-Hermitian effects. Specifically, these studies demonstrate the realization of exceptional points, topological phases, and enhanced dissipation mechanisms within strongly interacting many-body systems. Could this platform pave the way for novel quantum technologies leveraging non-Hermitian principles, such as robust quantum sensing and state manipulation?

The Inevitable Decay: Beyond Hermitian Boundaries

Conventional quantum mechanics, built upon the foundation of Hermitian Hamiltonians, inherently struggles to accurately model systems that interact with their surroundings or are actively driven by external forces. These Hamiltonians, requiring real eigenvalues representing measurable energy levels, preclude the description of processes involving gain or loss of energy – commonplace in open systems constantly exchanging energy with an environment. Consequently, phenomena like lasing, dissipation, and the behavior of quantum systems under continuous observation remain challenging to address within this traditional framework. The restriction to Hermitian operators effectively limits the scope of quantum mechanics, preventing a complete understanding of systems that are not isolated but rather dynamically coupled to their surroundings, necessitating an expansion beyond these conventional boundaries to fully capture the richness of quantum behavior.

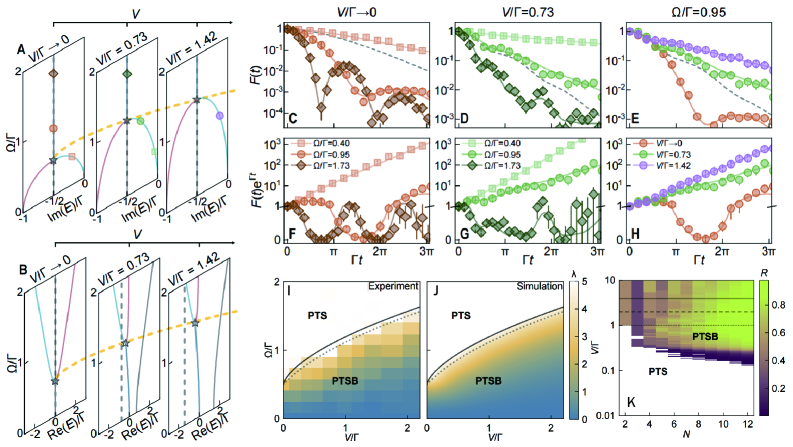

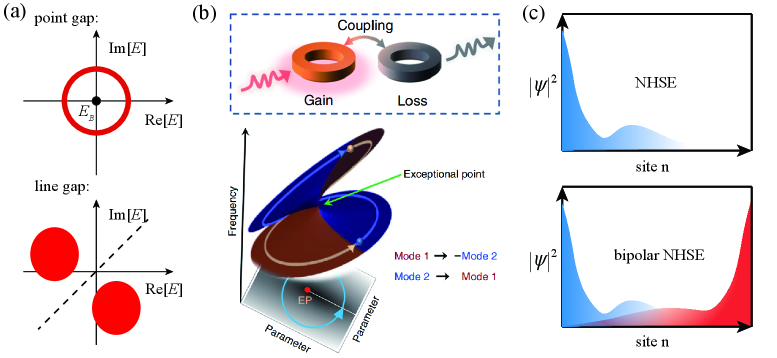

Non-Hermitian physics represents a significant departure from traditional quantum mechanics, offering a robust toolkit for investigating systems where energy isn’t conserved – a hallmark of open and driven systems. This framework explicitly incorporates the effects of gain and loss, previously treated as perturbations, directly into the quantum description. Consequently, phenomena absent in conventional Hermitian systems emerge, such as \mathcal{PT} -symmetry breaking leading to exceptional points-singularities in the parameter space where eigenstates coalesce. These exceptional points aren’t merely mathematical curiosities; they drastically alter the system’s sensitivity to perturbations and can enhance responses, opening doors for novel device designs and offering unique insights into areas like lasing, sensing, and topological physics. The exploration of non-Hermitian systems thus transcends theoretical advancement, providing a pathway to harness and understand previously inaccessible quantum behaviors.

The departure from Hermitian quantum mechanics demands a fundamental reassessment of long-held physical principles. Traditionally, energy is defined as a real eigenvalue of the Hamiltonian, ensuring the probability of a quantum state remains normalized over time; however, in non-Hermitian systems, eigenvalues can be complex, implying that energy is no longer necessarily conserved and states can exhibit growth or decay. This challenges the very definition of a stable quantum state, as conventional stability relies on a constant energy value. Consequently, researchers are compelled to redefine concepts such as the normalization of wavefunctions-often utilizing pseudo-Hermitian approaches or modified inner products-and to explore new criteria for determining the stability of quantum systems in the presence of gain and loss. This re-evaluation extends to the interpretation of quantum measurements, demanding a nuanced understanding of how non-Hermitian dynamics influence the outcomes and predictability of experiments.

The accurate depiction of non-equilibrium dynamics represents a fundamental shift in comprehending complex quantum systems, particularly those comprised of many interacting bodies. Traditional approaches often struggle with systems that are constantly exchanging energy with their surroundings – a scenario ubiquitous in nature. Dissipation, the process by which energy is lost from a system, and the resulting decay from equilibrium, are not merely imperfections to be minimized, but integral features shaping the system’s behavior. Investigations into non-Hermitian physics provide tools to model these open systems directly, allowing researchers to explore phenomena like exceptional points and topological phase transitions driven by gain and loss. This capability is essential for understanding diverse physical processes, ranging from laser dynamics and optomechanics to the behavior of biological systems and the evolution of quantum correlations in noisy environments – ultimately revealing a richer, more nuanced picture of quantum reality beyond static equilibrium.

Beyond Conventional Topologies: A New Quantum Landscape

Conventional topological systems are predicated on Hermitian Hamiltonians, ensuring real energy spectra and the preservation of probability. Non-Hermitian physics, however, relaxes this requirement, allowing for complex-valued potentials and Hamiltonians. This introduces phenomena like parity-time (PT) symmetry and exceptional points, which are not present in Hermitian systems. Consequently, non-Hermitian systems can host topological phases characterized by non-trivial topological invariants-such as winding numbers-that are inaccessible in their Hermitian counterparts. These novel phases are distinguished by unique boundary states and transport properties, expanding the scope of topological materials and devices beyond the limitations of traditional condensed matter physics. The presence of gain and loss allows for the creation of topological states with properties not achievable through solely manipulating band structure in Hermitian systems.

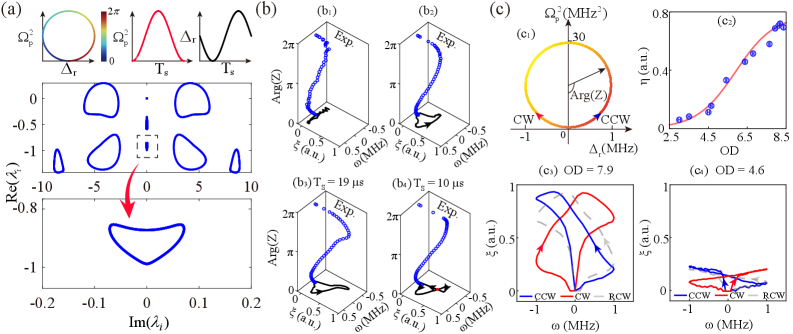

Generalizations of the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model to non-Hermitian systems introduce complex potentials or asymmetric hopping terms, resulting in modifications to the system’s energy spectrum and topological properties. While the standard SSH model features zero-energy edge states at the boundaries of a one-dimensional chain due to its topological nature, the non-Hermitian variant exhibits similar edge states, but their energies are no longer constrained to zero; they can reside in the complex plane. Furthermore, the topological invariant, typically a \mathbb{Z}_2 number characterizing the band structure, is altered in the non-Hermitian case and can be quantified by calculating winding numbers associated with the system’s quasi-energy spectrum. These non-Hermitian SSH models demonstrate that topological edge states can persist even with the inclusion of gain and loss, offering a pathway to control and manipulate these states through parameter tuning.

Non-Hermitian systems, characterized by the presence of gain and loss, exhibit topological protection through the manifestation of non-trivial winding numbers. Specifically, systems engineered with balanced gain and loss can support topologically protected edge states, evidenced by a quantized topological invariant – the winding number – taking on values of ±1. This winding number, calculated based on the system’s Hamiltonian in momentum space, directly reflects the net number of edge states and their chirality. A winding number of +1 indicates a counter-clockwise circulation of the eigenstate vector as it traverses the Brillouin zone, while -1 signifies clockwise circulation, both resulting in robust edge state protection against non-Hermitian perturbations. The observation of these non-zero winding numbers confirms the emergence of novel topological phases distinct from those found in conventional Hermitian systems.

The ability to engineer non-Hermitian systems allows for manipulation of topological states beyond the constraints of conventional Hermitian physics. Specifically, the introduction of gain and loss terms enables control over the band structure and associated topological invariants, such as the winding number. This control is demonstrated by the creation of robust edge states that are tunable via parameters governing the non-Hermitian terms. Furthermore, manipulating these parameters provides a pathway to actively switch between topologically distinct phases and tailor the properties of the resulting edge states, offering a degree of control previously unattainable in standard topological materials.

Rydberg Atoms: Sculpting Non-Hermitian Quantum Realities

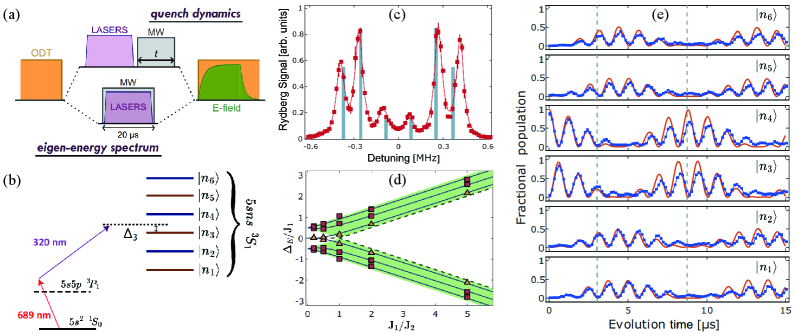

Rydberg atoms are uniquely suited for simulating non-Hermitian quantum systems due to the strength of their interactions and the precision with which their properties can be controlled. The large electric dipole moments associated with highly excited Rydberg states result in strong, long-range van der Waals interactions between atoms, which are crucial for engineering complex Hamiltonians. Furthermore, external fields – such as microwave or optical control – allow for precise tuning of these interactions and the introduction of dissipation. This controllability extends to manipulating atomic transitions, enabling the implementation of asymmetric hopping terms and on-site losses characteristic of non-Hermitian physics. These features facilitate the realization of effective Hamiltonians that deviate from the Hermitian requirement, allowing for the study of phenomena like exceptional points and their associated sensitivity enhancements.

Optical tweezer arrays utilize tightly focused laser beams to trap and position individual Rydberg atoms with micrometer precision. These arrays enable the creation of arbitrary and configurable lattice structures, allowing for tailored interatomic separations and geometries. By independently addressing each tweezer, researchers can arrange atoms in one-, two-, or three-dimensional configurations, and dynamically reconfigure the lattice during an experiment. This precise control over atomic positioning is critical for engineering specific interaction strengths and realizing complex quantum simulations, as the interaction strength between Rydberg atoms is highly dependent on the distance between them-scaling as 1/R^6 where R is the interatomic separation.

Non-Hermitian dynamics, characterized by complex energy eigenvalues and non-unitary time evolution, can be experimentally realized using Rydberg atoms through the introduction of dissipative coupling. This is achieved by engineering decay pathways that link atomic states, effectively mimicking optical loss or, conversely, gain when driven coherently. Specifically, these pathways introduce a constant flux of population between atomic levels, violating the requirements for Hermitian Hamiltonians – systems where the Hamiltonian equals its adjoint. The rate of dissipation, and thus the strength of the non-Hermitian effects, is directly controlled by the intensity of the driving fields and the coupling strength between the atomic states, allowing for tunable exploration of phenomena such as exceptional points and parity-time symmetry breaking in a quantum simulation.

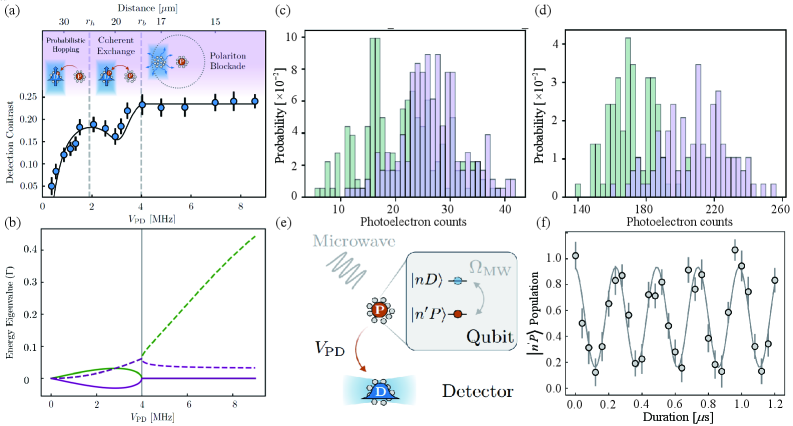

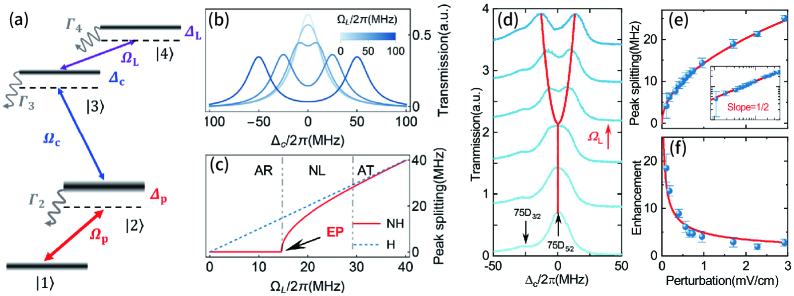

Rydberg atom arrays leverage internal atomic states to construct synthetic dimensions, enabling the simulation of non-Hermitian quantum models. By mapping degrees of freedom onto these internal states, researchers can engineer effective Hamiltonians exhibiting \mathcal{PT} -symmetry and explore phenomena like exceptional points. These exceptional points-singularities in the parameter space of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians-result in enhanced sensitivity to external perturbations. Specifically, experiments utilizing this approach have demonstrated a 20-fold increase in detection sensitivity compared to conventional methods, owing to the divergence of the system’s response near the exceptional point and providing a pathway for precision measurements and novel sensing applications.

Amplified Sensitivity and the Promise of Non-Hermitian Detection

Rydberg atom arrays are proving to be a versatile platform for investigating the unusual behavior predicted by non-Hermitian physics, particularly through the observation of exceptional points. These points represent singularities in the parameter space of a quantum system, where eigenvalues and eigenvectors coalesce, leading to enhanced sensitivity to external perturbations. By carefully controlling the interactions between Rydberg atoms – highly excited states with exaggerated properties – researchers can engineer systems exhibiting non-Hermitian characteristics. The observation of these exceptional points isn’t merely a theoretical confirmation; it demonstrates a dramatic increase in the system’s response to minute changes in its environment. This heightened sensitivity stems from the broken parity-time symmetry inherent in non-Hermitian systems, allowing for amplified detection of external stimuli and opening avenues for the development of ultra-sensitive sensors and novel quantum devices.

Loschmidt echo measurements offer a refined method for assessing the resilience of quantum states when subjected to external disturbances. This technique essentially tracks how faithfully a quantum system retraces its evolution after a brief perturbation – a ‘kick’ to the system – and compares it to its unperturbed trajectory. A diminished echo signal indicates a heightened sensitivity to these perturbations, revealing the rate at which information about the initial state is lost. Crucially, the Loschmidt echo isn’t merely a measure of stability; it provides quantitative insight into the nature of that instability, characterizing the system’s susceptibility to decoherence and allowing researchers to pinpoint the dominant mechanisms driving state degradation. This capability is particularly valuable when investigating complex quantum systems where traditional stability analyses fall short, offering a powerful tool for both fundamental research and the development of robust quantum technologies.

The Autler-Townes effect and electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) vividly illustrate how light and matter interact within non-Hermitian systems, revealing a delicate balance between absorption and dispersion. These phenomena, typically observed when a strong control field is applied alongside a weak probe field, create a ‘transparency window’ in an otherwise opaque medium. This isn’t a true absence of interaction, but rather a redistribution of light absorption, leading to a dramatic reduction in absorption at specific frequencies and an accompanying steep change in the refractive index. Within the context of non-Hermitian systems, where energy is not necessarily conserved, these effects are significantly enhanced and become exquisitely sensitive to external perturbations, highlighting the potential for manipulating light propagation and designing novel optical devices with unprecedented control over electromagnetic fields. The interplay allows for observation of unconventional light-matter interactions and provides a pathway to explore and harness the unique properties of these engineered quantum systems.

The realization of a remarkably sensitive quantum system, exhibiting a measured sensitivity of 22.68 nV cm-1 Hz-1/2, signifies a considerable advancement with implications extending beyond fundamental physics. This heightened responsiveness to external perturbations allows for the potential development of exquisitely precise sensors capable of detecting incredibly weak forces or fields. Such sensitivity could revolutionize fields like materials science, enabling the characterization of subtle structural changes, and environmental monitoring, facilitating the detection of trace amounts of pollutants. Furthermore, this capability positions Rydberg atom arrays as promising candidates for building advanced quantum technologies, including highly sensitive magnetometers and novel approaches to quantum information processing where precise control and readout of quantum states are paramount.

Forging Ahead: The Future of Non-Hermitian Quantum Technologies

The Non-Hermitian XY chain has emerged as a particularly tractable system for investigating complex quantum phenomena within the rapidly developing field of Rydberg atom arrays. This model, diverging from traditional quantum mechanics by allowing for non-Hermitian Hamiltonians – those lacking the requirement that an operator equals its adjoint – enables the simulation of open quantum systems and the exploration of parity-time ( \mathcal{PT} ) symmetry breaking. Researchers leverage the highly controllable interactions between Rydberg atoms – atoms excited to a high energy level – to physically realize this chain, offering a platform to observe unconventional phase transitions and dynamic behaviors not readily accessible in closed systems. Specifically, the non-Hermitian nature introduces effective long-range interactions and modifies the energy spectrum, leading to phenomena like exceptional points and enhanced sensitivity to external perturbations, ultimately offering new avenues for quantum information processing and sensing.

The realization of stable and dependable quantum devices hinges on a nuanced understanding of symmetry breaking within non-Hermitian systems. Unlike traditional quantum mechanics where symmetries guarantee predictable behavior, non-Hermitian systems – those lacking the constraint that an operator equals its conjugate transpose – exhibit exceptional sensitivity to perturbations. This sensitivity can lead to spontaneous symmetry breaking, where a system settles into a state that lacks the symmetries of the underlying Hamiltonian. However, recent theoretical and experimental work demonstrates that carefully engineered non-Hermitian Hamiltonians can control this symmetry breaking, creating protected states and suppressing unwanted decoherence. Specifically, exploiting parity-time ( \mathcal{PT} ) symmetry and other non-Hermitian features allows for the creation of robust quantum states that are less vulnerable to environmental noise, ultimately paving the way for more reliable quantum computation and sensing technologies. Manipulating these broken symmetries provides a novel mechanism for tailoring quantum system behavior and enhancing device performance.

The burgeoning field of non-Hermitian physics, traditionally explored within condensed matter systems, is demonstrating remarkable adaptability to diverse quantum platforms. Researchers are actively investigating how the unique properties – such as exceptional points and non-unitary evolution – inherent to non-Hermitian systems can be engineered in platforms like trapped ions, superconducting circuits, and photonic lattices. This extension isn’t merely theoretical; it promises to unlock functionalities unattainable in conventional quantum devices. Specifically, non-Hermitian designs offer pathways to enhance sensing precision, create novel topological phases with increased robustness against decoherence, and develop quantum simulators capable of exploring previously inaccessible physical phenomena. The potential lies in manipulating the flow of quantum information in unconventional ways, ultimately leading to a new generation of quantum technologies with enhanced performance and entirely new capabilities.

Non-Hermitian quantum simulation represents a burgeoning field poised to redefine the boundaries of both fundamental physics and quantum engineering. Unlike traditional quantum simulations which operate within the confines of Hermitian systems – those with real energy eigenvalues – exploring non-Hermitian systems, where energy eigenvalues can be complex, allows researchers to model open quantum systems and phenomena previously inaccessible. This capability unlocks the potential to investigate areas like exceptional points – singularities in the parameter space where quantum states dramatically change – and parity-time symmetry breaking, offering insights into topological phases of matter and novel sensing mechanisms. Crucially, the ability to simulate these exotic quantum states isn’t merely theoretical; it provides a pathway toward building fundamentally new quantum devices with enhanced sensitivity, robustness against decoherence, and unique functionalities, potentially revolutionizing fields like quantum computing, metrology, and materials science by leveraging the unusual properties of non-Hermitian dynamics.

The study of Rydberg atom arrays reveals a compelling truth about physical systems-their inherent impermanence. These systems, manipulated to explore non-Hermitian physics, demonstrate that decay isn’t necessarily destructive, but a fundamental aspect of existence. As John Dewey observed, “Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.” Similarly, this research isn’t simply about observing exceptional points or topological phases; the very act of probing these fleeting states is the system’s life cycle unfolding. The observed dissipation, rather than a flaw, becomes integral to the system’s behavior, showcasing how improvements and alterations inevitably reshape its essence over time. The research highlights that understanding the dynamics of change is more crucial than striving for static perfection.

The Horizon Recedes

The exploration of non-Hermitian physics through Rydberg atom arrays represents not a destination, but a controlled destabilization. Each observation of an exceptional point, each engineered dissipation, is less a solution and more a carefully charted acceleration of the inevitable-the system’s entropic march. The current work illuminates a pathway, but the true challenge lies in understanding what emerges from the decay, not simply documenting its progression. The platform’s versatility is undeniable, yet the limitations of controlling complex many-body interactions-the inherent ‘graininess’ of reality-will invariably dictate the boundaries of observation.

Future investigations will likely shift from seeking increasingly exotic topological phases to understanding how these phases degrade, how their robustness is genuinely tested by the very dissipation used to reveal them. The promise of enhanced quantum sensing is intriguing, but every sensor introduces its own disturbance, its own subtle erosion of the measured state. Technical debt, in this context, isn’t simply code to be refactored, but the very act of measurement altering the timeline of the system under scrutiny.

Ultimately, the field will be defined not by what can be built within these arrays, but by what is allowed to happen. The most profound insights may not be those deliberately engineered, but those revealed by the system’s graceful-or not so graceful-acceptance of its own impermanence. Every bug, every unintended consequence, will become a moment of truth in the timeline, a signal of the system’s evolving character.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.07372.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- James Gunn & Zack Snyder’s $102 Million Remake Arrives Soon on Netflix

- Stargate’s Reboot Is More Exciting Thanks to This Other Sci-Fi Series Revival (Which Was Cancelled Too Soon)

- Where Winds Meet has skills inspired by a forgotten 20-year-old movie, and it’s absolutely worth watching

- Breaking: Bitcoin Stumbles as Altcoins Make a Daring Entrance! 😂💰

2026-02-10 17:34