Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new geometric approach uses the subtle forms of gravitational waves to rigorously test Einstein’s theory and search for signs of new physics.

Singular value decomposition is employed to identify key waveform features for improved parameter estimation and mitigation of degeneracies in tests of general relativity.

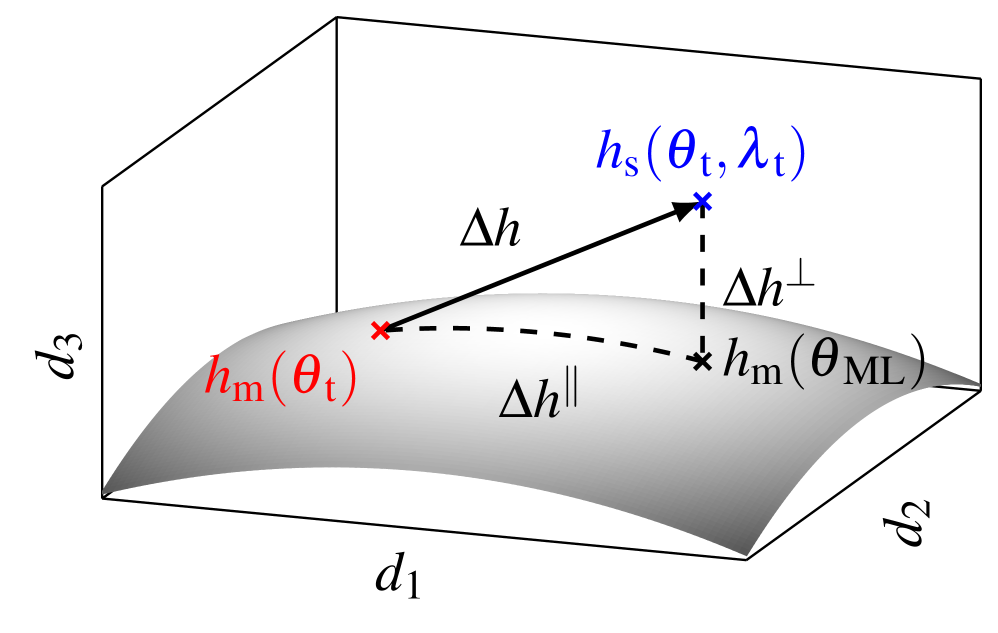

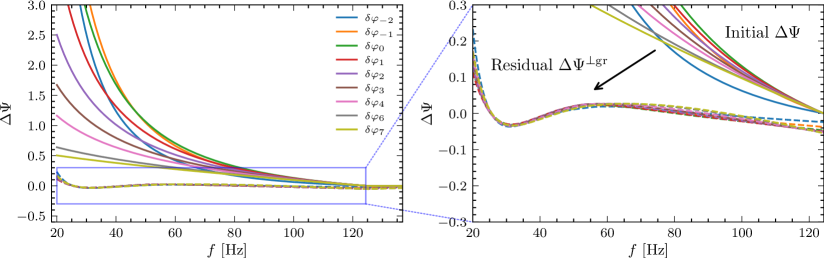

Distinguishing genuine deviations from general relativity within gravitational wave signals remains a central challenge in modern astrophysics. This is addressed in ‘Inspiral tests of general relativity and waveform geometry’, which introduces a geometric framework for analyzing inspiral waveforms and rigorously testing Einstein’s theory. By leveraging singular value decomposition, this work demonstrates that the detectability of deviations is intrinsically linked to the geometry of the waveform manifold, allowing for the construction of optimal templates and mitigation of parameter degeneracies. Could this approach reveal subtle modifications to general relativity currently hidden within gravitational wave data, and ultimately reshape our understanding of gravity?

Breaking the Mold: Why Gravity’s Rules Demand Re-evaluation

Despite its remarkable success in predicting gravitational phenomena, General Relativity (GR) isn’t necessarily the final word on gravity. While GR accurately describes gravity in most scenarios – from planetary orbits to the bending of light – its predictions haven’t been rigorously tested in the most extreme gravitational environments. Black hole mergers and the very early universe represent such frontiers, where gravity is incredibly strong and dynamic. Subtle deviations from GR’s predictions could arise in these conditions, potentially revealing the influence of quantum gravity or the existence of previously unknown fields. Therefore, ongoing and future gravitational wave observations, coupled with theoretical advancements, are crucial for probing the limits of GR and searching for evidence of new physics that might reshape our understanding of the cosmos.

Contemporary gravitational wave astronomy largely relies on theoretical templates derived from Einstein’s General Relativity to identify signals amidst the noise of detectors. While remarkably successful in confirming GR’s predictions, this methodology inherently constrains the search for deviations indicating new physics. By exclusively seeking waveforms predicted by GR, current analyses may overlook subtle signals that don’t neatly fit existing models-signals potentially originating from phenomena like modified gravity theories, extra dimensions, or exotic compact objects. This limitation underscores a critical challenge: the universe may be communicating through gravitational waves that current detectors are effectively ‘tuned out’ to hear, necessitating the development of more versatile and adaptable search strategies.

The continued refinement of gravitational wave detection necessitates the development of waveform models that extend beyond the predictions of General Relativity. Current analyses, largely predicated on Einstein’s theory, may inadvertently filter out signals hinting at new physics; subtle deviations from expected waveforms – perhaps indicating extra dimensions, modified gravity, or the presence of exotic compact objects – could be dismissed as noise. Consequently, researchers are prioritizing the creation of adaptable waveform templates, capable of accommodating a broader range of theoretical possibilities, and allowing for a more comprehensive search for signals that challenge our understanding of gravity. These flexible models aren’t designed to replace General Relativity, but rather to function as a crucial tool for rigorously testing its limits and uncovering potential new phenomena hidden within the cosmos.

Beyond Einstein: A Framework for Gravity’s Evolution

The parameterized post-Einsteinian (ppE) framework facilitates the modeling of gravitational dynamics beyond General Relativity (GR) by introducing a set of parameters that quantify potential modifications to the GR field equations. Rather than constructing entirely new theories of gravity, ppE builds upon the well-established GR formalism, adding higher-order terms parameterized by values representing the strength of deviations from GR predictions. These parameters, typically denoted as α, β, and others, systematically account for effects like variations in the post-Newtonian expansion, polarization of gravitational waves, and modifications to propagation speed. The consistent implementation of these parameters ensures that, in the limit where all parameters approach zero, the framework recovers standard General Relativity, providing a robust and mathematically sound basis for testing alternative gravitational theories and constraining their parameters with observational data.

The parameterized post-Einsteinian (ppE) framework extends General Relativity by introducing a set of parameters that quantify potential modifications to the gravitational dynamics. These parameters, denoted as α, β, and others, represent deviations from the predictions of GR in various sectors of the gravitational interaction. Specifically, these parameters modulate terms in the post-Newtonian expansion of the waveform, allowing for systematic investigation of alternative theories of gravity. By constraining these parameters through gravitational wave observations – such as measurements of waveform phase or amplitude – scientists can test the validity of GR and establish limits on the strength of potential deviations, effectively probing the underlying nature of gravity itself.

Generating accurate gravitational waveforms within the parameterized post-Einsteinian (ppE) framework and performing parameter estimation necessitate substantial computational resources. Waveform generation involves solving the Einstein field equations to high precision, often employing numerical relativity techniques or sophisticated approximations like effective-one-body methods, particularly when strong-field effects are significant. Parameter estimation, crucial for testing modifications to General Relativity, requires evaluating the likelihood of observed signals given various parameter values; this typically involves computationally intensive Bayesian inference methods such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) or nested sampling algorithms. Furthermore, the high dimensionality of the parameter space-including intrinsic source parameters and the ppE parameters quantifying deviations from GR-increases the computational burden, demanding optimized algorithms and high-performance computing infrastructure.

Distilling Complexity: Reducing Dimensionality for Precise Measurement

Parameter estimation for precessed parameterized waveforms (ppE) is complicated by the high dimensionality of the parameter space, typically involving seven to eight dimensions to fully describe the binary system and its orientation. This high dimensionality arises from parameters defining the masses of the component black holes, spin magnitudes and directions, and the inclination and polarization of the gravitational wave signal. The volume of this parameter space grows exponentially with the number of dimensions, requiring a correspondingly large number of waveform templates or sophisticated sampling techniques to accurately map the likelihood surface and determine parameter uncertainties. Consequently, computational cost and the potential for degeneracies between parameters become significant obstacles to efficient and reliable parameter estimation from gravitational wave data.

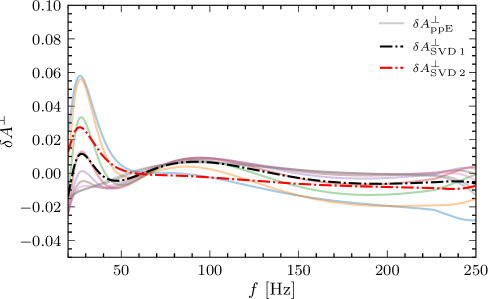

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is employed as a dimensionality reduction technique to address the challenges posed by the high-dimensional parameter space in gravitational wave (GW) data analysis. SVD decomposes the parameter space’s covariance matrix, identifying principal components-orthogonal directions corresponding to the largest variances. By projecting the parameter space onto these dominant components, the effective dimensionality is reduced while retaining most of the relevant information for parameter estimation. This allows for more efficient sampling of the parameter space with methods like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), decreasing computational cost and improving the speed with which parameter uncertainties can be determined. The number of retained singular values, and thus the dimensionality of the reduced space, is determined by a chosen threshold based on the explained variance, balancing computational efficiency against the loss of information.

The Fisher Matrix and covariance matrix are fundamental tools in gravitational wave parameter estimation. The Fisher Matrix, calculated from the likelihood function’s second derivatives, provides an estimate of the parameter uncertainty, with its inverse yielding the covariance matrix Σ. The diagonal elements of Σ represent the estimated variance – and standard deviation – for each parameter, quantifying the expected precision with which that parameter can be measured. Off-diagonal elements indicate correlations between parameters; significant non-zero values suggest that uncertainty in one parameter will impact the estimation of others. Accurate calculation of these matrices is essential for assessing the detectability of signals and designing optimal observation strategies, as well as for properly interpreting the results of parameter estimation analyses.

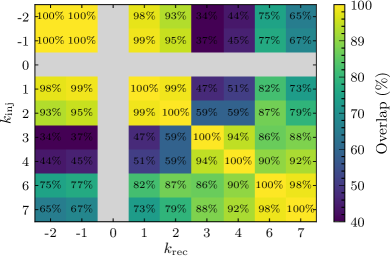

BayesFactor analysis serves as a quantitative method for model comparison by calculating the ratio of the marginal likelihoods of competing hypotheses. The sensitivity of BayesFactor results is directly related to the degree of waveform overlap between the models being compared; greater overlap increases the ability to differentiate between them. Furthermore, the residual signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) significantly impacts the analysis; a higher SNR in the residual – the difference between the observed data and the model prediction – strengthens the evidence provided by the BayesFactor, while low SNR values can lead to inconclusive or unreliable results. Therefore, careful consideration of waveform similarity and residual SNR is essential when interpreting BayesFactor values and drawing conclusions about model evidence.

The Future of Gravitational Astronomy: A Networked Universe

Existing gravitational wave observatories, like LIGO and Virgo, are already placing limits on parameters describing deviations from Einstein’s General Relativity, but a new generation of detectors promises a substantial leap forward. Cosmic Explorer and the Einstein Telescope, currently under development, will boast significantly enhanced sensitivities and broadened frequency ranges, enabling the observation of weaker and more distant signals. This improved capability is crucial for precisely constraining parameters associated with Post-Planckian Effective (ppE) field theories, which attempt to describe the universe at energies approaching the Planck scale. By analyzing gravitational waves from merging compact objects, these detectors will probe the very fabric of spacetime and potentially reveal subtle signatures of new physics beyond our current understanding, pushing the boundaries of gravitational wave astronomy and fundamental physics.

Future gravitational wave astronomy relies heavily on expanding beyond Earth-based observatories. Space-based detectors, including the planned LISA mission, and the Chinese Taiji and TianQin projects, alongside concepts like BDECIGO and TianGO, are poised to unlock a new era of discovery. These instruments are designed to be sensitive to much lower frequency gravitational waves than their ground-based counterparts, LIGO and Virgo. This difference in sensitivity is crucial because lower frequencies are emitted by supermassive black hole mergers and other cataclysmic events in the early universe, phenomena largely inaccessible to current detectors. By combining data from these space- and ground-based networks, scientists aim to achieve a more complete picture of the gravitational universe, enhancing detection rates and enabling more precise measurements of astrophysical parameters. This multi-messenger approach promises to reveal previously hidden details about the cosmos and test the limits of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity.

The synergistic operation of multiple gravitational wave detectors – both ground-based facilities like LIGO and Virgo, and future space-based observatories such as LISA – represents a crucial strategy for pushing the boundaries of fundamental physics. By combining data from networks spanning different locations and sensitivities, scientists can significantly enhance the detection of faint signals and precisely measure the characteristics of gravitational waves. This multi-detector approach isn’t simply about increasing signal strength; it’s about breaking signal degeneracies and enabling the rigorous testing of General Relativity in extreme regimes. Subtle deviations predicted by alternative theories, or arising from exotic astrophysical phenomena, become statistically distinguishable when analyzed with combined datasets. This collaborative effort promises to unlock a deeper understanding of the universe, revealing new physics beyond the Standard Model and challenging existing cosmological paradigms.

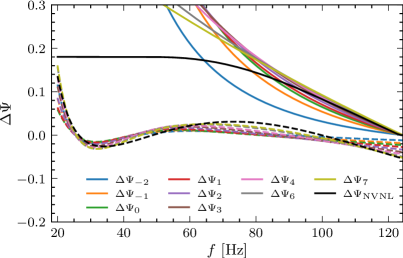

Investigations into alternative theories of gravity, such as NonViolentNonLocality, are poised to benefit substantially from the coordinated operation of current and forthcoming gravitational wave detectors. Analyses reveal that the waveforms predicted by these models exhibit a significant degree of overlap – ranging from 0.3 to 0.6 – with those predicted by General Relativity, a dependence influenced by the specific parameters chosen within the GR framework. Crucially, the ability to detect a bias towards these alternative models is demonstrably linked to the residual signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), with a z-score representing the strength of this detection scaling linearly with the residual SNR. This direct correlation suggests that the synergistic data analysis from multiple detectors – ground-based facilities and space-based observatories – will be instrumental in either confirming or refuting these deviations from established gravitational theory and precisely quantifying the extent of any observed discrepancies.

The pursuit of knowledge, as demonstrated in this exploration of gravitational waves, inherently demands a willingness to challenge established frameworks. This research doesn’t simply accept general relativity as immutable; instead, it actively probes its limits through rigorous testing and geometric analysis. It echoes John Dewey’s sentiment: “Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.” The process of testing the theory, of meticulously analyzing waveforms with singular value decomposition to identify potential deviations, is the advancement of understanding. By focusing on detectable deviations and addressing parameter degeneracies, the study embodies this philosophy – learning through actively reshaping existing models, not passively accepting them. This isn’t about confirming what is known, but about revealing what remains to be discovered.

Beyond the Signal

The presented framework, while illuminating detectable deviations from general relativity, necessarily rests upon assumptions about the nature of what lies beyond. Singular value decomposition, a tool for dissecting signal, reveals not the underlying architecture of alternative gravity, but merely the spaces where deviations are most readily exposed. The true test isn’t simply finding a discrepancy; it’s deciphering what that discrepancy means. One might argue that identifying the easiest ways to break a model is more revealing than the model itself.

Parameter degeneracies, even when mitigated, remain ghosts in the machine. The pursuit of precision demands a reckoning with the inherent limitations of observation. Future work must move beyond waveform modeling as a purely constructive exercise and embrace it as a diagnostic tool – probing the boundaries of the parameter space not to find a best-fit alternative, but to define the contours of the unknown. The signal, after all, is only a fragment of a larger, perhaps fundamentally unknowable, structure.

Ultimately, the value of this approach lies not in confirming or denying general relativity-a binary outcome that feels increasingly artificial-but in refining the questions. Each detected deviation, each mitigated degeneracy, is an invitation to disassemble the prevailing assumptions and rebuild them, not necessarily stronger, but differently. It reminds that chaos is not an enemy, but a mirror of architecture reflecting unseen connections.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17524.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- ‘Crime 101’ Ending, Explained

- Battlefield 6 Season 2 Update Is Live, Here Are the Full Patch Notes

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- Netflix’s Stranger Things Replacement Reveals First Trailer (It’s Scarier Than Anything in the Upside Down)

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- How to Froggy Grind in Tony Hawk Pro Skater 3+4 | Foundry Pro Goals Guide

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Wife Swap: The Real Housewives Edition Trailer Is Pure Chaos

2026-02-20 16:37