Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research demonstrates how boundary conditions shape the energy spectrum of quantum fields in accelerated frames, offering insights into particle creation.

This review details the mathematical framework for analyzing Rindler’s spectral anomaly using the Klein-Gordon and Maxwell equations with self-adjoint extensions.

The emergence of quantized field modes in accelerated frames, as predicted by the Unruh effect, remains a subtle issue when considering realistic boundaries. This is explored in ‘The effects of boundary conditions on Rindler’s spectral anomaly’, which investigates the impact of reflecting boundaries on the spectral properties of Klein-Gordon and Maxwell fields in Rindler spacetime. The analysis reveals that specific boundary conditions induce a discrete energy spectrum, effectively quantizing the field, and can be understood through an anomalous potential coupled with Dirichlet conditions. What are the broader implications of these findings for understanding particle creation in curved spacetime and the nature of quantum vacuum fluctuations?

The Relativistic Vacuum: A Challenge to Intuition

The conventional understanding of a vacuum – empty space devoid of matter – is fundamentally challenged by the Unruh effect, a prediction stemming from the marriage of quantum field theory and special relativity. This counterintuitive phenomenon posits that an accelerating observer doesn’t experience this vacuum as truly empty, but rather as a thermal bath of particles, akin to being immersed in a faint glow of heat. This isn’t a statement about the physical reality of particles appearing, but a consequence of how acceleration alters the observer’s perception of quantum fields. What appears as zero-point energy to a stationary observer is reinterpreted by the accelerating observer as real particles with a quantifiable temperature – a temperature directly proportional to the acceleration experienced. Consequently, the very definition of ‘empty space’ becomes relative, dependent on the observer’s state of motion, suggesting that the vacuum isn’t simply a void, but a dynamic entity shaped by the principles of relativity.

The Unruh effect’s startling claim – that acceleration transforms vacuum into a heat bath – doesn’t emerge from simple intuition, but from a rigorous marriage of quantum field theory and special relativity. This necessitates a sophisticated mathematical framework because the very definition of a vacuum state is observer-dependent within the principles of relativity. Standard calculations of quantum fields, typically performed in inertial frames, break down when considering accelerating observers; the particle content perceived changes dramatically. Specifically, the effect stems from the fact that an accelerating observer detects particles that an inertial observer would identify as virtual particles – fleeting quantum fluctuations. This detection isn’t a matter of sensing pre-existing particles, but the accelerating frame fundamentally creating real particles from the vacuum due to the energy supplied by the acceleration, a process mathematically described by transformations involving the RWA (Rotating Wave Approximation) and Bogoliubov transformations which relate particle creation and annihilation operators between different frames.

Analyzing quantum fields within non-inertial frames-those undergoing acceleration-presents a formidable challenge to physicists, requiring substantial departures from standard calculational techniques. The conventional methods used to describe quantum fields rely heavily on the assumption of an inertial, or non-accelerating, observer. However, acceleration introduces complexities arising from the changing nature of the vacuum state itself; what appears as empty space to a stationary observer is perceived as a fluctuating sea of particles by an accelerating one. This necessitates the application of Bogoliubov transformations, a mathematical tool that relates the particle content as seen by different observers, and significantly complicates the normally straightforward calculations of field behavior. Consequently, seemingly simple predictions about particle creation and annihilation become intertwined with the observer’s state of motion, demanding a rigorous re-evaluation of fundamental concepts like vacuum energy and particle number within the framework of quantum field theory and special relativity.

Rindler Spacetime: Geometry and its Implications

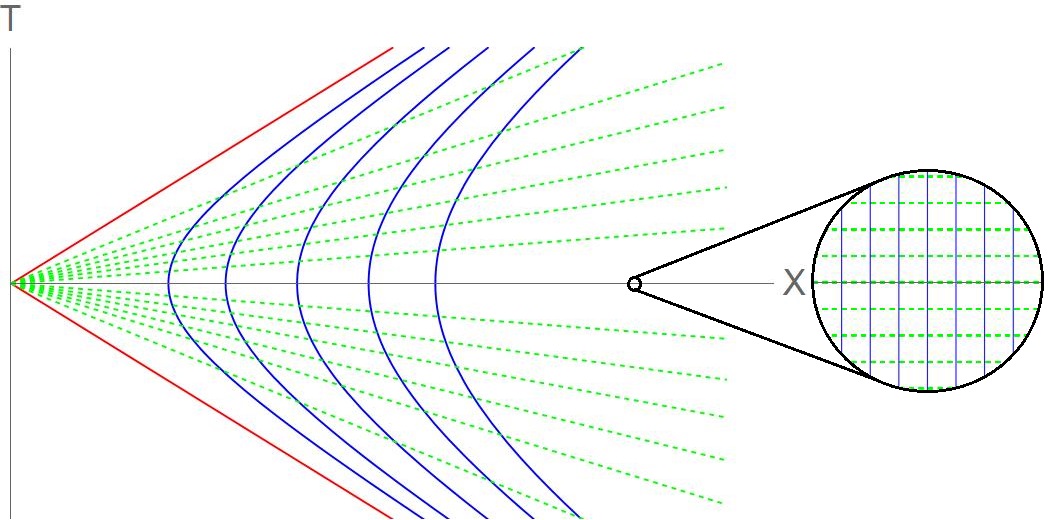

The Rindler metric, defined in coordinates (t, x), describes the spacetime geometry experienced by an observer with constant proper acceleration in special relativity. Specifically, it provides a coordinate system where the acceleration is constant, allowing for the treatment of uniformly accelerated frames as equivalent to inertial frames. This metric is given by ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2, where x is the spatial coordinate along the direction of acceleration. Crucially, the Rindler metric introduces a horizon at x = 0, analogous to the event horizon of a black hole, impacting the definition of positive frequency solutions necessary for field quantization. The use of the Rindler metric enables the application of standard quantum field theory techniques to analyze fields in non-inertial frames, providing a foundational framework for understanding phenomena like Hawking radiation and Unruh effect.

Solutions to the Klein-Gordon and Maxwell equations in Rindler spacetime (t, x) exhibit characteristics distinct from those in flat Minkowski spacetime. Specifically, the curvature of Rindler space, defined by a constant acceleration, introduces an effective potential term not present in the flat-space equations. This potential arises from the Christoffel symbols in the Rindler metric and manifests as an addition to the standard mass or charge-related potential terms. For the Klein-Gordon equation, this results in a modified frequency relationship for plane waves, and for the Maxwell equations, it alters the propagation of electromagnetic fields, leading to phenomena such as particle creation as observed by the uniformly accelerating frame. The strength of this anomalous potential is directly related to the magnitude of the constant acceleration defining the Rindler space.

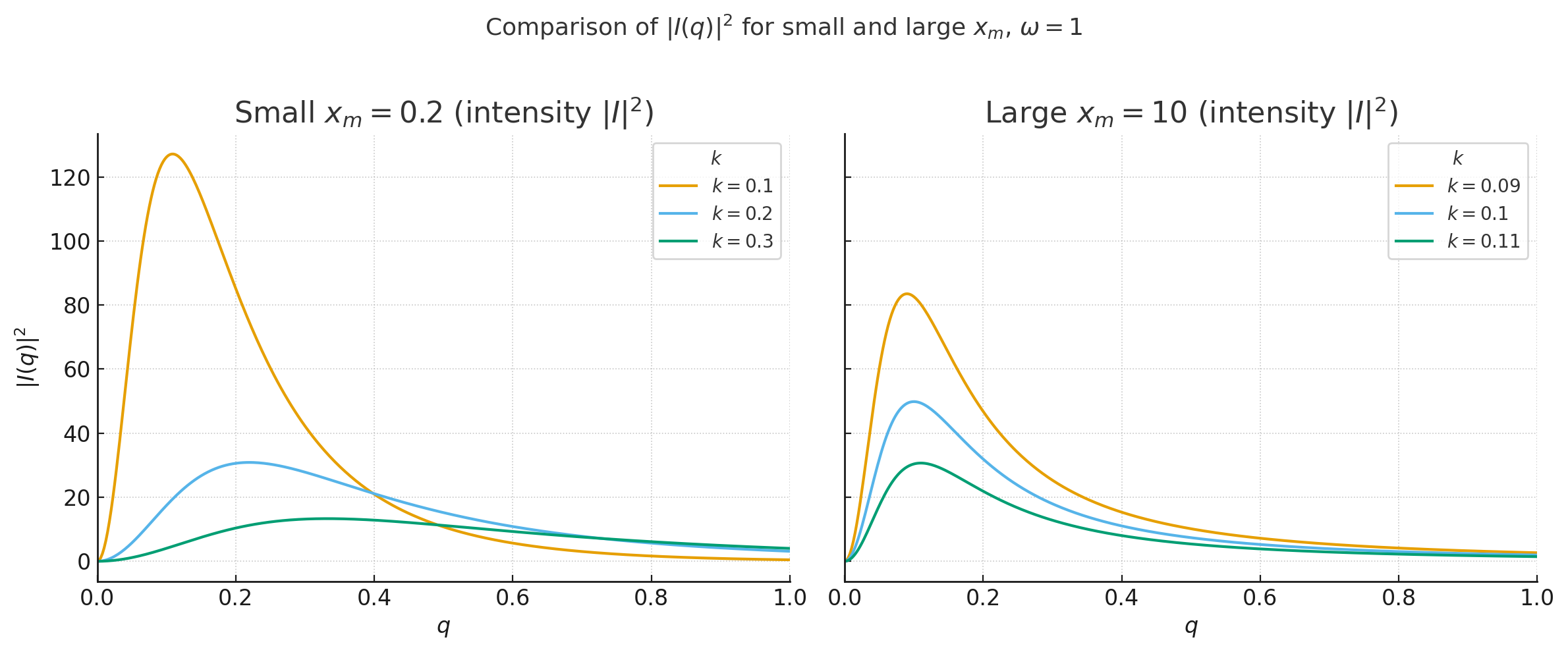

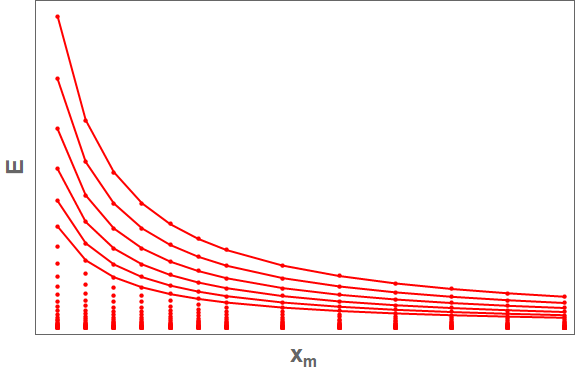

The location of the boundary condition, parameterized by x_m, is a critical parameter in calculations involving quantum fields in curved spacetime. Wave function decay rates are directly dependent on x_m; a larger value generally corresponds to slower decay and increased persistence of quantum fluctuations. Furthermore, the convergence of integrals arising in calculations of Green’s functions and propagator terms is significantly affected by x_m. Improperly positioned boundary conditions – either too close to or too far from the event horizon – can lead to divergent integrals, necessitating careful selection of x_m to ensure physically meaningful and numerically stable results. This parameter effectively controls the regularization of the field theory in the curved background.

The anomalous potential observed in curved spacetime arises directly from the influence of the Christoffel symbols, which represent the gravitational force as a geometric property of spacetime. This potential term modifies the standard Klein-Gordon or Maxwell equations, altering the field’s equation of motion and consequently its behavior. Specifically, the potential introduces a spatial dependence to what would otherwise be a constant mass or charge term, effectively creating a non-trivial background for quantum field propagation. The magnitude of this potential is directly proportional to the curvature of spacetime, meaning that stronger gravitational fields result in a more significant alteration of the quantum field’s characteristics, including its energy levels and particle creation rates. Calculations involving this potential necessitate careful consideration of the spacetime metric g_{\mu\nu} and its derivatives, as these determine the form and strength of the anomalous term within the field equations.

Spectral Solutions: Harnessing Mathematical Rigor

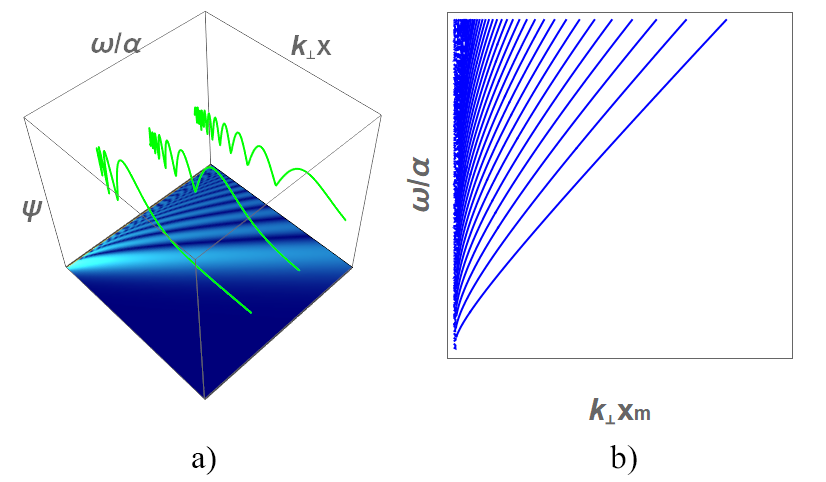

Solutions to the Klein-Gordon and Maxwell equations within the Rindler spacetime, a non-inertial coordinate system simulating constant acceleration, are formally expressed using Hankel functions of the first and second kind, H^{(1)}_{v}(x) and H^{(2)}_{v}(x), respectively. These functions arise naturally when separating variables in the wave equation within Rindler coordinates. However, their application necessitates careful mathematical treatment due to their complex behavior, particularly concerning convergence and normalization. The order of the Hankel function, v, is directly related to the particle’s momentum and the Rindler acceleration. A robust analysis requires consideration of branch cuts and appropriate limiting procedures to ensure physically valid solutions, as standard techniques applicable to plane wave solutions in Minkowski spacetime are insufficient due to the curved nature of Rindler space.

Sturm-Liouville theory offers a mathematical structure for examining second-order linear differential equations, specifically those arising from the Klein-Gordon and Maxwell equations in Rindler spacetime. This theory guarantees that solutions are physically relevant by establishing conditions for self-adjointness, which ensures real eigenvalues and a well-defined spectrum of observable quantities. The framework involves defining a weight function, w(x), and a differential operator that, when applied to a function, yields another function with specific properties. By satisfying the criteria of Sturm-Liouville theory – including the requirement that w(x) is positive definite – the resulting solutions are demonstrably Hermitian, ensuring that probability densities remain positive and physically interpretable. Furthermore, the theory provides tools for analyzing the completeness and orthogonality of these solutions, which are essential for constructing a basis for representing general physical states.

The definition of appropriate boundary conditions is essential for obtaining a physically valid spectrum of particles when solving differential equations like those arising in Rindler spacetime. These conditions ensure the resulting operator is self-adjoint, a mathematical requirement for observable, real-valued energy eigenvalues. A common approach utilizes a “piston boundary” model, which effectively truncates the spatial domain and imposes constraints on the field behavior at that boundary. The specific implementation of this boundary condition dictates the allowed modes of solution and, consequently, the quantization of particle momenta and energies; improper boundary conditions can lead to unphysical results, such as negative probabilities or non-normalizable states. The choice of boundary condition is therefore directly linked to the definition of the Hilbert space in which the quantum mechanical problem is formulated.

The parameter α, representing acceleration in the Rindler spacetime, directly influences the analytic properties of solutions to the Klein-Gordon and Maxwell equations. Specifically, increasing values of α introduce stronger non-analytic behavior, manifested as singularities in the solutions. This non-analyticity arises from the coordinate transformation between Minkowski and Rindler spacetime, and its severity is proportional to α. Consequently, the field configurations – including particle creation rates and vacuum state properties – are significantly altered by variations in α, necessitating careful consideration of its value when interpreting physical results. The impact extends to the spectrum of allowable solutions and the associated boundary conditions required for a self-adjoint operator.

Analysis of wave function convergence in Rindler spacetime indicates that the rate of decrease in weight distribution, as a function of photon momentum k, is demonstrably either exponential or quadratic. Specifically, the convergence behavior is dictated by the characteristics of the solutions to the relevant differential equations under defined boundary conditions. Exponential convergence implies a rapid attenuation of the wave function with increasing momentum, while quadratic convergence represents a slower, yet still defined, decrease in amplitude. This distinction is crucial for accurately modeling particle behavior and predicting field configurations within the accelerated reference frame, impacting calculations of particle densities and spectral properties.

The Quantum Vacuum: A Dynamic Reality

The quantum vacuum, often perceived as empty space, is in fact a dynamic realm where virtual particles constantly appear and disappear. This framework allows for a deeper understanding of how virtual photons contribute to the polarization of this vacuum – a phenomenon critical to explaining the Unruh effect. Polarization arises from the fleeting existence of these particle-antiparticle pairs, creating temporary separations of charge that respond to acceleration. An accelerating observer experiences these fluctuations as real particles, effectively ‘seeing’ a thermal bath of radiation even in the absence of any conventional heat source. This isn’t a matter of detecting pre-existing particles, but the acceleration inducing the perception of them from the continuous creation and annihilation of virtual photons within the polarized vacuum. The strength of this perceived thermal radiation is directly linked to the observer’s acceleration, solidifying the vacuum’s role as not merely a void, but a fundamental component of spacetime with measurable physical consequences.

The behavior of virtual particles arising from the quantum vacuum is not random, but rather dictated by the principles of the little group, a fundamental concept in physics relating to symmetry and transformations. This group determines the allowable quantum numbers – such as spin and polarization – that these fleeting particles can possess. Consequently, the little group doesn’t simply allow any virtual particle to emerge; it constrains their properties, influencing how they contribute to the overall thermal spectrum observed in phenomena like the Unruh effect. Specifically, the representation of the little group defines the possible states of these particles, and the density of these states directly impacts the perceived temperature. A careful analysis of these representations reveals how the quantum vacuum, while seemingly empty, is actually a dynamic arena where the little group sculpts the characteristics of virtual particles and, ultimately, the thermal radiation arising from accelerated observers.

The Unruh effect dramatically alters the conventional understanding of empty space, revealing the quantum vacuum not as a void, but as a dynamic realm teeming with fleeting, fluctuating quantum fields. This isn’t merely a theoretical curiosity; it suggests that an accelerating observer perceives this vacuum as a thermal bath of particles, despite an inertial observer registering nothing. These aren’t ‘real’ particles in the classical sense, but virtual particles constantly popping into and out of existence, a consequence of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the inherent quantum nature of spacetime. The effect fundamentally challenges the notion of a universal vacuum state, demonstrating that the perception of emptiness is relative to the observer’s motion and, crucially, that even in the absence of matter, energy can manifest due to the very structure of spacetime itself.

The behavior of virtual particles within the quantum vacuum is governed by a specific relationship between their energy, or frequency ω, and their momentum. This connection isn’t simply proportional, as classical physics might suggest; instead, the frequency is determined by considering both the transverse component of momentum q – representing motion perpendicular to the direction of observation – and the parallel component q_{parallel}, which describes movement along that line of sight. The dispersion relation, expressed as \omega = \sqrt{q^2 + q_{parallel}^2}, demonstrates that a particle’s frequency isn’t solely dictated by its speed, but also by the configuration of its momentum in space, fundamentally altering how these fleeting particles contribute to phenomena like the Unruh effect and revealing the complex, dynamic nature of what is often called ’empty’ space.

The pursuit of self-adjoint operators, central to this work on Rindler space quantization, echoes a fundamental challenge in epistemology. As David Hume observed, “A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence.” This article doesn’t prove a specific physical reality within the Rindler metric; rather, it rigorously explores the consequences of imposing particular boundary conditions on the Klein-Gordon and Maxwell equations. The resulting discrete energy spectrum isn’t a revelation of nature’s hidden order, but a mathematically consistent outcome-a testament to the power of deduction, constrained by chosen axioms. It’s a model, exquisitely crafted, but still, a mirror of its maker, not a perfect reflection of what is.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The insistence on self-adjoint extensions to address boundary conditions in Rindler space, while mathematically rigorous, highlights a recurring discomfort. The spectral anomaly isn’t so much explained as it is managed – pushed into a framework where predictable, discrete spectra emerge. Future work must grapple with the physical interpretation of these chosen boundary conditions. Are they imposed by some deeper, yet unknown, principle? Or are they merely artifacts of a perturbative approach to strong field quantization, an admission that current techniques are insufficient? Replication of these results, utilizing entirely different mathematical formalisms, is paramount; if it can’t be replicated, it didn’t happen.

Further investigation into the connection between these boundary conditions and the emergence of horizons seems critical. The Rindler metric, after all, is a local approximation to curved spacetime. Does a more complete treatment, incorporating global spacetime geometry, relax the need for such stringent conditions? Or will the anomaly persist, demanding a fundamental re-evaluation of particle concepts near accelerating observers? The exploration of analogous phenomena in more complex spacetimes – those possessing genuine event horizons – may prove illuminating, or simply reveal further layers of complexity.

Ultimately, the true test will lie in predictive power. Can a theoretical framework built upon these principles yield experimentally verifiable consequences? The Unruh effect, while conceptually intriguing, remains stubbornly elusive. A more precise understanding of the spectral anomaly, and the boundary conditions that govern it, may provide the necessary tools to finally bridge the gap between theory and observation, or, more likely, expose the limitations of the entire endeavor.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.07323.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Gold Rate Forecast

- How to Build a Waterfall in Enshrouded

- The Legend of Zelda Film Adaptation Gets First Photos Showcasing Link and Zelda in Costume

- Guide: Marathon Server Slam Gets Underway Today – Here’s Everything You Need to Know

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- New PS4 Game Announced for 2027 (When the PS6 Is Supposed to Release)

- 10 Best Shoujo Manga Writers

2026-02-10 19:14