Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals a link between quantum geometry, entanglement, and material properties, offering a powerful way to characterize electronic behavior in both ionic and covalent insulators.

Inelastic X-ray scattering is used to experimentally probe quantum geometric bounds, including the Bures metric and quantum Fisher information, revealing insights into electronic localization and bonding.

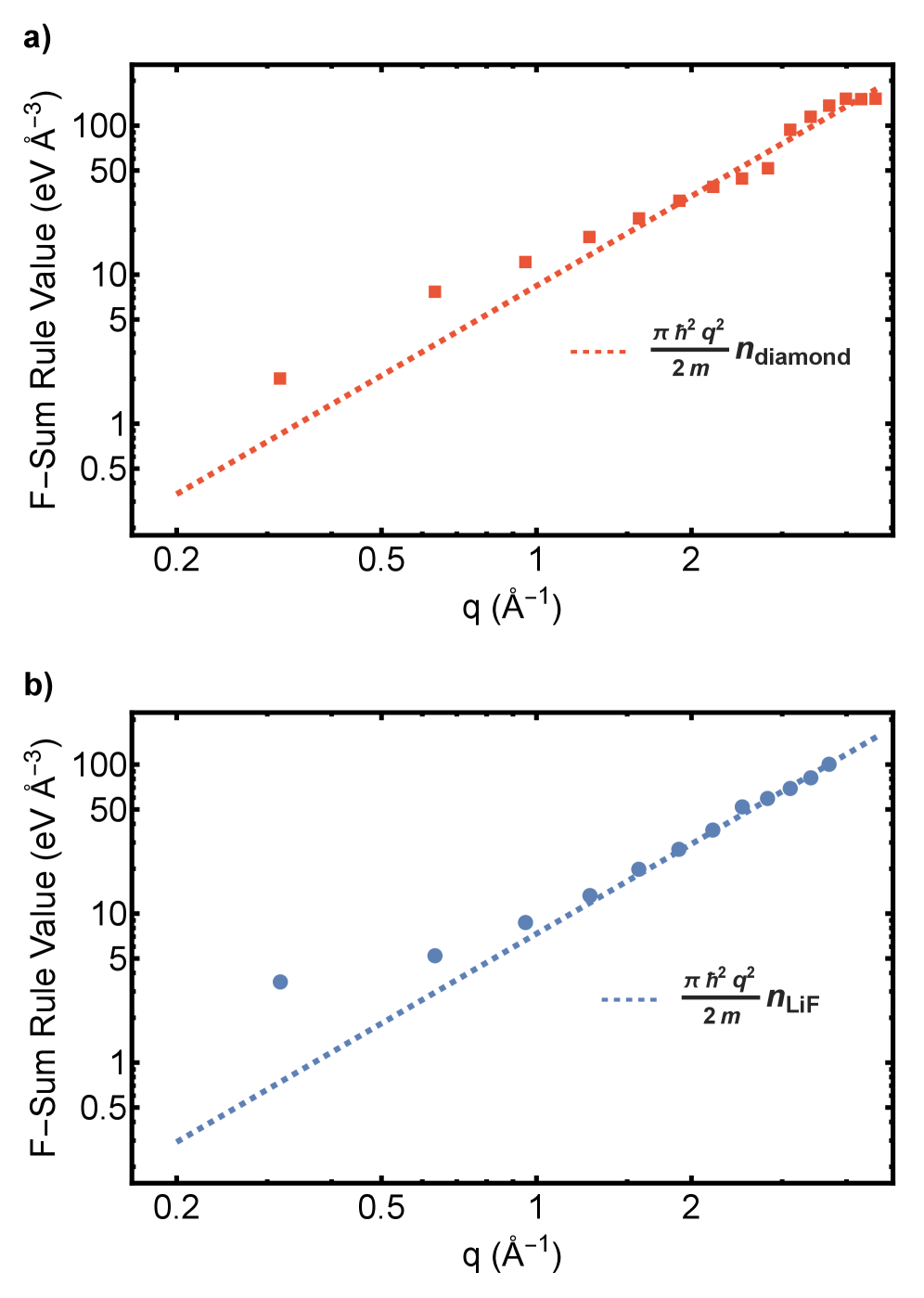

While quantum geometry dictates fundamental material properties, direct experimental access to these geometric features has remained elusive. Here, in ‘Fundamental Tests of Quantum Geometric Bounds in Ionic and Covalent Insulators using Inelastic X-Ray Scattering’, we demonstrate that inelastic x-ray scattering directly probes quantum geometry, quantitatively determining the Bures metric and quantum Fisher information in both covalently bonded diamond and ionically bonded LiF. These measurements reveal that covalent bonds exhibit a greater degree of electronic delocalization and a higher density of quantum information compared to ionic bonds, establishing a direct link between quantum information, electron localization, and chemical bonding. Could this approach unlock new strategies for designing materials with tailored quantum properties and functionalities?

Beyond Conventional Descriptions: Geometry as the Foundation of Quantum Systems

Conventional quantum mechanics, while remarkably successful in describing isolated systems, encounters significant limitations when applied to the intricate realm of many-body systems. These systems, comprised of numerous interacting particles, exhibit emergent properties – behaviors that cannot be predicted from the characteristics of individual components. Traditional approaches, relying heavily on wave function analysis, struggle to capture the collective behavior and topological features arising from these interactions. The sheer complexity of describing all possible particle arrangements and their associated energies quickly becomes computationally intractable, hindering the prediction of material properties like superconductivity or exotic magnetism. This inadequacy stems from a focus on the details of the quantum state, rather than the underlying geometry of the quantum state space itself, necessitating new frameworks capable of characterizing these complex systems beyond simple wave function descriptions.

The Quantum Geometric Tensor represents a significant advancement in characterizing quantum systems by moving beyond traditional approaches focused solely on wave functions. This tensor isn’t simply a replacement, but a generalization, elegantly unifying two key geometric concepts: Berry curvature and the Quantum Metric. Berry curvature describes how a quantum state evolves due to external perturbations, while the Quantum Metric quantifies the intrinsic distance between infinitesimally close quantum states. By encapsulating both within a single mathematical object, the tensor provides a complete description of the quantum state geometry – essentially, the shape of the space in which quantum information resides. This holistic view allows researchers to predict a system’s response to external stimuli and understand emergent phenomena with greater accuracy, offering insights inaccessible through conventional methods focused on Ψ alone. The ability to characterize this geometric landscape is proving crucial for advancements in materials science and the development of novel quantum technologies.

The behavior of many materials isn’t dictated solely by the particles within them, but by the very geometry of their quantum states – a landscape extending far beyond traditional wave function analysis. This geometric perspective, leveraging concepts like the Quantum Metric and Berry curvature encapsulated within the Quantum Geometric Tensor, offers a means to predict and ultimately control material properties in ways previously inaccessible. Instead of focusing on individual particle characteristics, this approach considers how the system responds to changes in its quantum state, revealing emergent phenomena and enabling the design of materials with tailored functionalities. Understanding this geometric landscape promises advancements in fields like superconductivity, topological materials, and quantum computing, where subtle changes in quantum state geometry can dramatically alter macroscopic behavior, paving the way for innovative technologies.

Probing Quantum Geometry: Methods for State Characterization

Inelastic X-ray Scattering (IXS) offers a method for directly measuring the Quantum Weight, a quantity reflecting the sensitivity of a quantum state to perturbations. This measurement is achieved by analyzing the energy transfer during the scattering process, which is directly proportional to the dynamic structure factor S(q, \omega). The dynamic structure factor describes the time-dependent density fluctuations within the system and, crucially, provides the information needed to calculate the Quantum Weight. The Quantum Weight, therefore, serves as a link between experimentally accessible scattering data and the underlying quantum properties of the system, allowing for quantification of state distinguishability and sensitivity to external influences.

The Quantum Weight (QW) represents a generalization of the Quantum Fisher Information (QFI), offering a measure of distinguishability between quantum states that is particularly sensitive to variations in the static structure factor. While QFI typically focuses on parameter estimation, the QW incorporates information about the underlying state itself, enhancing its ability to detect subtle differences. Accurate determination of the QW necessitates precise knowledge of the static structure factor, S(q), which describes the spatial correlations within the quantum system. The QW is calculated using an integral involving S(q) and the derivative of the quantum state with respect to a parameter, effectively quantifying how much the state changes with respect to that parameter as revealed by the static structure factor.

The Bures distance is a metric used to quantify the distinguishability between quantum states, with its calculation fundamentally rooted in the fidelity between those states. Fidelity, represented as F(\rho, \sigma) = Tr(\sqrt{\rho}\sqrt{\sigma}), provides a measure of the overlap between two density matrices ρ and σ. The Bures distance is then defined as D_B(\rho, \sigma) = \sqrt{1 - F(\rho, \sigma)}. Importantly, the Bures metric, derived from the Bures distance, has a demonstrated connection to the longitudinal component of the quantum metric tensor; this relationship allows for geometric characterization of the quantum state space, effectively mapping the ‘distance’ between states in a geometrically meaningful way and enabling analysis of how states change under perturbations.

Material Response: Connecting Geometry to Electrical Conductivity

The Quantum Metric, denoted as g_{ij}, directly quantifies the sensitivity of the electronic band structure to perturbations in momentum space, and is fundamentally linked to the longitudinal conductivity \sigma_x. This connection arises because the Quantum Metric determines how charge carriers – electrons or holes – respond to applied electric fields. Specifically, the conductivity tensor component relating to current flow in the x-direction is proportional to the trace of the Quantum Metric multiplied by the carrier density and scattering time. A larger Quantum Metric indicates a greater sensitivity of the band structure and, consequently, a higher conductivity for a given carrier density and scattering rate. Therefore, the Quantum Metric serves as a key descriptor of charge transport properties, predicting how efficiently a material conducts electricity based on its band structure geometry.

The dissipative component of electrical conductivity, responsible for energy loss as heat, is directly proportional to the magnitude of fluctuations in the electronic structure as quantified by the Quantum Metric. This relationship arises because the Quantum Metric, \mathcal{Q} , characterizes the sensitivity of electronic states to perturbations; larger fluctuations necessitate greater energy dissipation to maintain current flow. Specifically, the rate of energy loss is determined by the spectral properties of the Quantum Metric, with higher spectral density at low frequencies indicating increased dissipation. Therefore, materials exhibiting significant fluctuations in their electronic structure, as measured by a large Quantum Metric, will inherently display higher dissipative conductivity and greater energy loss during charge transport.

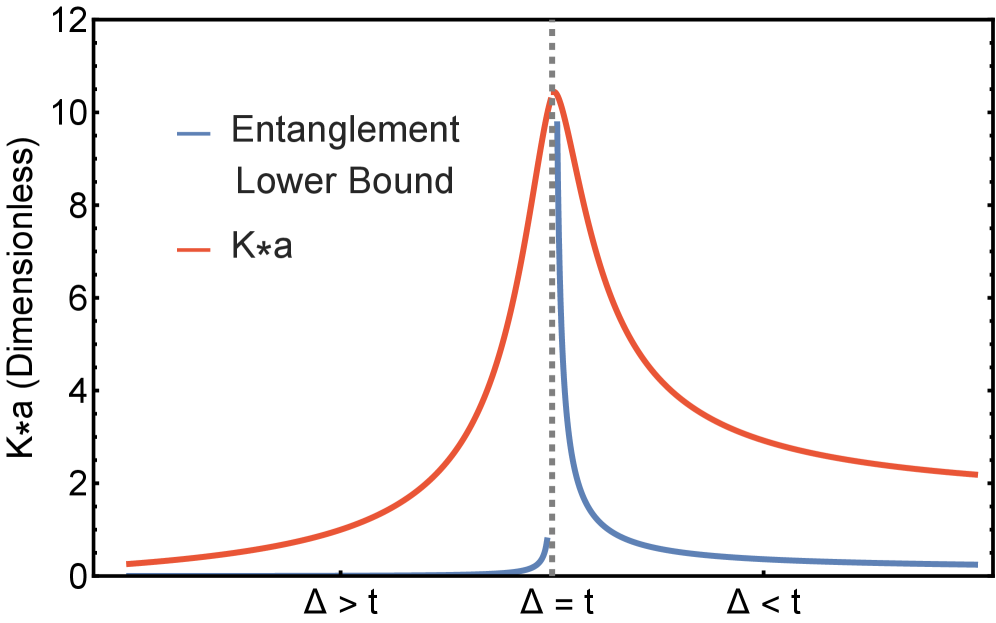

Geometric control over material properties is demonstrable through the relationship between twisted boundary conditions and the Quantum Metric. Theoretical derivations establish bounds on the Quantum Fisher Information – a measure of sensitivity to parameter changes – directly linking it to both the entanglement entropy and the static structure factor of the material. Specifically, manipulating twisted boundary conditions alters the entanglement entropy, which subsequently impacts the Quantum Fisher Information, indicating a pathway to tune material responsiveness. The static structure factor, characterizing the spatial correlations within the material, also contributes to these bounds, solidifying the connection between geometric constraints and measurable material properties like conductivity and sensitivity to external stimuli. This suggests that controlled geometric distortions can be leveraged to engineer materials with specific, tailored characteristics.

Topological Insights: Entanglement and Model Systems

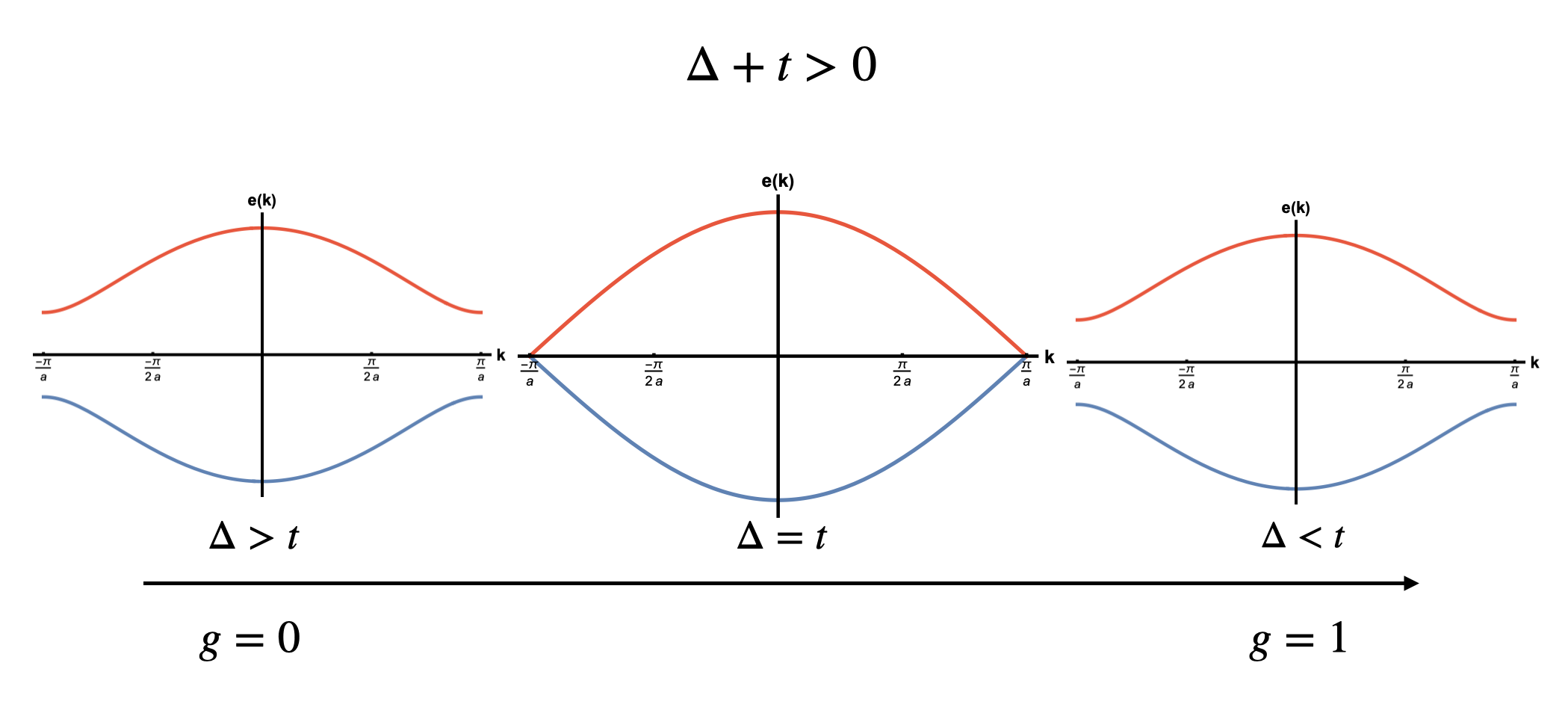

The Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model and its broader counterpart, the Tight-Binding Model, aren’t simply mathematical conveniences; they are fundamentally built upon the principles of quantum entanglement. These models, originally developed to understand phenomena like conductivity in polyacetylene, reveal how electrons become correlated and their fates intertwined across multiple atoms. This entanglement isn’t a side effect, but rather the very mechanism driving the unique properties predicted by topology – properties like the existence of protected edge states. Consequently, these models have become indispensable testbeds for exploring geometric concepts in quantum mechanics, allowing researchers to simulate and predict the behavior of complex materials where entanglement dictates their electronic and optical characteristics. By manipulating the parameters within these models, scientists can effectively ‘design’ entanglement and explore its role in creating materials with novel functionalities.

The Quantum Weight offers a refined perspective on entanglement within condensed matter systems, moving beyond simple pairwise correlations to quantify the total amount of quantum connectedness. This measure isn’t merely theoretical; it has been directly probed using Inelastic X-ray Scattering (IXS), a technique sensitive to collective electronic excitations. Crucially, experimental results align with predictions based on the nature of chemical bonding: materials exhibiting strong covalent character, where electrons are tightly shared, demonstrate a higher Quantum Weight compared to those with ionic bonding, where electrons are more localized. This consistency validates the Quantum Weight as a robust descriptor of entanglement and suggests its potential for characterizing and predicting material properties based on their underlying electronic structure, offering a pathway to materials design informed by quantum connectedness.

The convergence of theoretical models – such as the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger and Tight-Binding frameworks – with advanced experimental techniques is now enabling the rational design of materials exhibiting specific topological characteristics. Recent studies demonstrate a quantifiable link between a material’s inherent covalent bond character and its Quantum Fisher Information, providing a predictive tool for engineering desired functionalities. Specifically, derived bounds on this information correlate strongly across diverse systems, from the simplified SSH model – a cornerstone of topological physics – to the complex structure of diamond. This capability promises a future where materials are not simply discovered, but meticulously crafted with tailored electronic and optical properties, potentially revolutionizing fields like quantum computing and advanced sensing.

The pursuit of understanding material properties, as demonstrated in this work concerning quantum geometric bounds, echoes a fundamental principle of mathematical rigor. The paper’s exploration of the Bures metric and its connection to electronic localization necessitates a precise, unambiguous definition of these geometric quantities. As Thomas Hobbes stated, “The chain of consequences is as long as itself, and admits no end,” implying that a logically sound framework, meticulously defined, is crucial for tracing the relationship between quantum geometry and measurable physical phenomena. The researchers’ methodology, focused on establishing a demonstrable connection between quantum Fisher information and linear response, exemplifies this demand for provable, rather than merely observed, correlations within complex systems.

Where to Next?

The demonstrated correspondence between the Bures metric, quantum Fisher information, and linear response-while conceptually satisfying-remains largely a theoretical exercise. The challenge now shifts from establishing the connection to extracting genuinely predictive power. Simply measuring entanglement-or approximating its influence-is insufficient; the formalism demands a quantifiable link between geometric curvature and observable material properties, a link currently obscured by the inherent complexity of many-body systems. Further refinement of the theoretical framework, particularly regarding the applicability of linear response in strongly correlated regimes, is essential.

A persistent limitation lies in the computational expense of accurately determining the quantum Fisher information for realistic materials. Approximations, such as those leveraging twisted boundary conditions, offer a pragmatic path forward, but at the cost of introducing systematic errors. The field requires innovative algorithms-ones rooted in mathematical elegance rather than brute-force computation-to efficiently and reliably map out the quantum geometric landscape of condensed matter. Only then can one hope to distinguish genuine geometric effects from spurious artifacts.

Ultimately, the true test of this framework will be its ability to resolve long-standing puzzles in materials science-to explain phenomena that remain stubbornly resistant to conventional explanations. Whether it will prove to be a fundamental breakthrough or merely an aesthetically pleasing detour remains to be seen. The consistency of the mathematical structure is, of course, reassuring; however, nature is rarely constrained by human notions of beauty.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.19054.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Sunday Rose Kidman Urban Describes Mom Nicole Kidman In Rare Interview

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Sad the Battlefield 6 Open Beta is over? I am, too, but hey — Battlefield 2042 just got a surprise new Update 9.2, and it has BF6 rewards for everyone that plays it

- All 6 Takopi’s Original Sin Episodes, Ranked

2026-01-29 00:50