Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach to modeling electron transfer processes leverages phase space electronic structure to provide a more accurate depiction of molecular interactions.

This review details how a phase space framework improves the description of diabatic couplings, vibronic energy gaps, and nonadiabaticity in electron transfer reactions by accounting for both nuclear and electronic momentum.

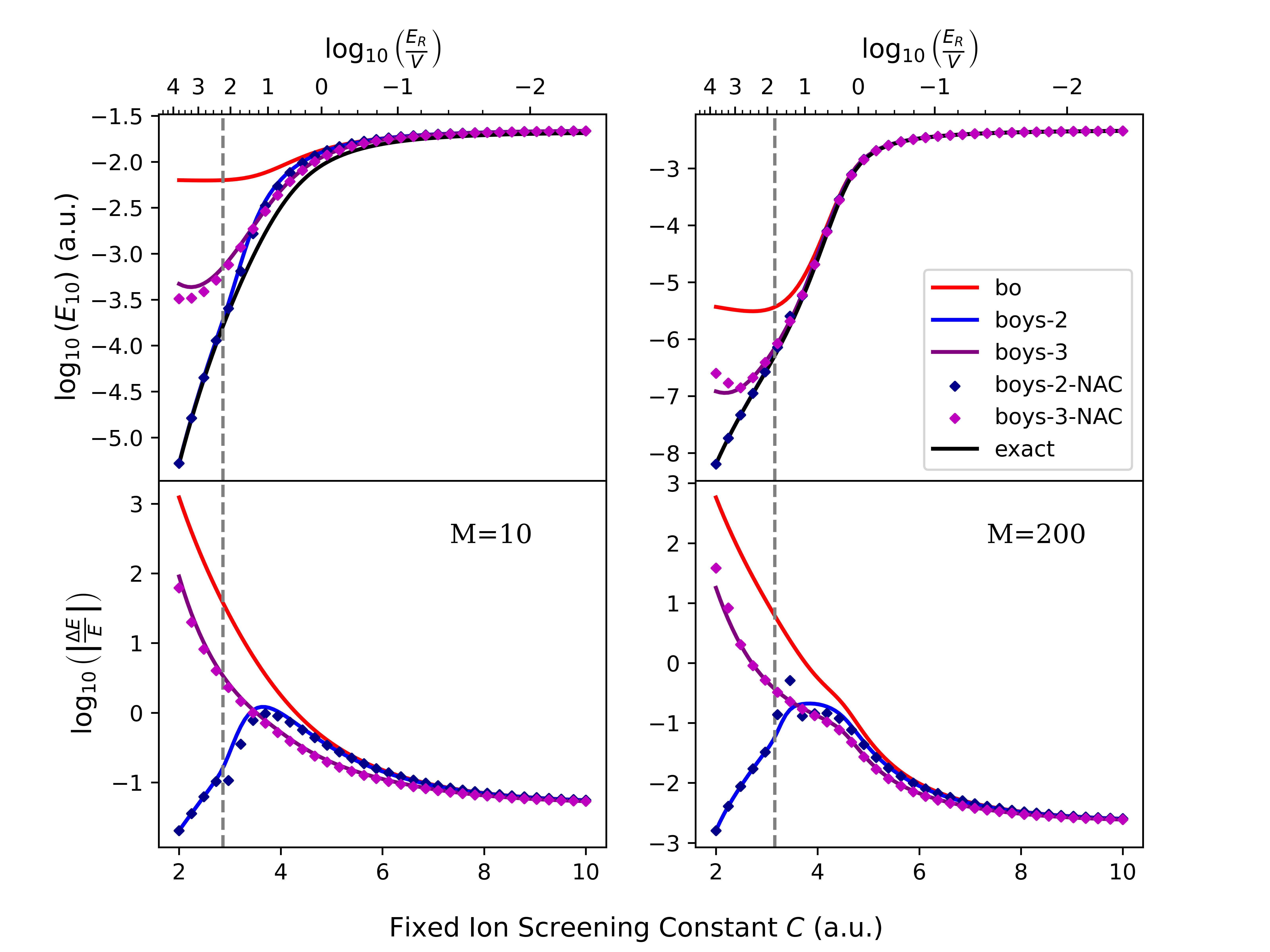

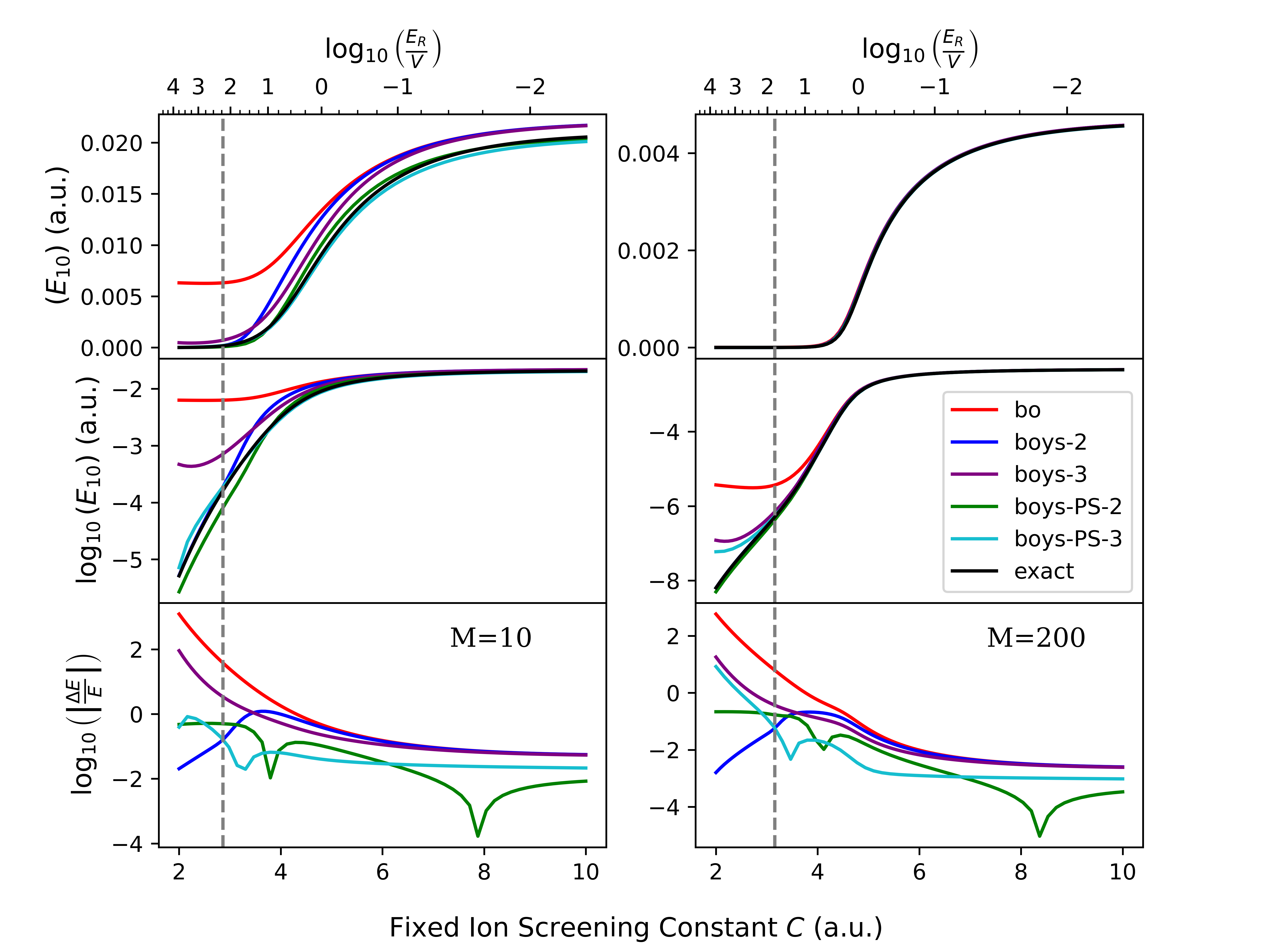

Describing nonadiabatic dynamics-where electronic and nuclear motions are strongly coupled-remains a significant challenge in theoretical chemistry and physics. This is addressed in ‘Electron Transfer, Diabatic Couplings and Vibronic Energy Gaps in a Phase Space Framework’, which investigates an alternative to the traditional Born-Huang approach by formulating an electronic Hamiltonian within a phase space framework. The authors demonstrate that this phase space treatment consistently yields vibrational energy gaps with errors an order of magnitude smaller than those obtained using the standard Born-Huang method, particularly when considering both position and momentum. Could this framework ultimately provide a more efficient and accurate means of modeling spin-dependent electron transfer and other complex nonadiabatic processes?

The Limits of Elegant Theories: When Born-Oppenheimer Breaks Down

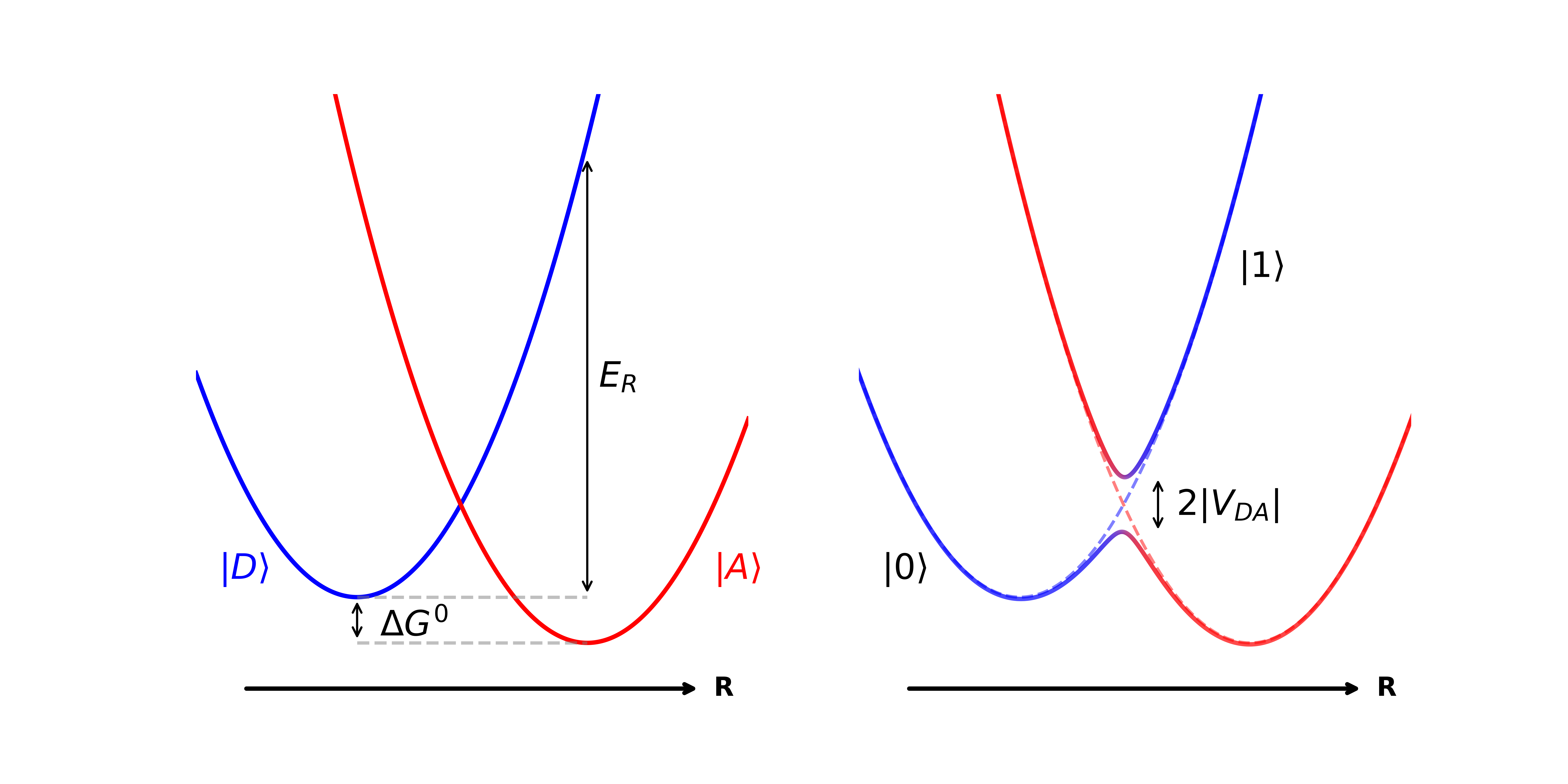

Conventional molecular dynamics simulations routinely employ the Born-Oppenheimer approximation to simplify calculations, treating the motion of electrons and nuclei as independent due to the significant mass difference between them. This decoupling allows researchers to calculate the forces on atoms based on a fixed electronic structure, dramatically reducing the computational cost of simulating molecular behavior. Essentially, the assumption is that electrons respond instantaneously to any changes in nuclear positions, effectively creating a potential energy surface on which the nuclei move. While remarkably successful for many systems, this approximation introduces limitations, particularly when considering scenarios where electronic and nuclear motions become strongly coupled, such as during chemical reactions or in excited states – necessitating more complex computational approaches to accurately model these processes.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation, while computationally efficient, falters when molecules approach regions where the potential energy surfaces representing different electronic states intersect – a phenomenon known as a conical intersection. At these points, the electronic and nuclear motions become inextricably linked, and the separation inherent in the Born-Oppenheimer approach is no longer valid. This breakdown is particularly relevant in photochemistry and chemical reactions, where molecules can rapidly transition between electronic states, a process termed a nonadiabatic transition. Consequently, accurate modeling of these events – crucial for understanding vision, photosynthesis, and many industrial processes – demands methodologies that go beyond the standard approximation, explicitly incorporating the coupling between electronic and nuclear degrees of freedom to capture the full complexity of molecular behavior.

Precisely simulating molecular dynamics in scenarios where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation fails necessitates computational approaches that treat electrons and nuclei as interacting, rather than separate, entities. These methods, often termed nonadiabatic dynamics, move beyond simply calculating forces on atoms from a fixed electronic structure; instead, they actively evolve both nuclear and electronic wavefunctions concurrently. This demands solving the full molecular Schrödinger equation, a computationally intensive task, but is crucial for understanding phenomena like photochemical reactions, vision, and energy transfer in complex systems. Techniques range from surface hopping, which allows trajectories to ‘hop’ between different electronic states, to more rigorous approaches like multi-configurational time-dependent Hartree-Fock, each offering varying levels of accuracy and computational cost in capturing the intricate interplay between electronic and nuclear motion.

Beyond Fixed Coordinates: Capturing Coupled Dynamics with Phase Space Electronic Structure

Phase Space Electronic Structure (PSES) theory departs from traditional electronic structure approaches by explicitly incorporating both nuclear position and momentum as parameters defining electronic states. Instead of solely utilizing coordinates to define the nuclear configuration, PSES employs a complete set of coordinates and momenta – (R, P) – to fully specify the nuclear wavefunction. This parameterization allows for the direct construction of potential energy surfaces as functions of both position and momentum, enabling a more accurate description of nuclear dynamics, particularly in situations where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down. By treating momentum as a variable, PSES provides a natural framework for investigating nonadiabatic transitions and other phenomena sensitive to the kinetic energy of the nuclei.

Traditional adiabatic representations of molecular potential energy surfaces assume that electronic and nuclear motions are separable, and that the system remains in a single electronic state during evolution. However, when potential energy surfaces come close together, this approximation breaks down, leading to nonadiabatic coupling – the transfer of electronic probability between states. Phase Space Electronic Structure Theory directly incorporates both nuclear positions and momenta into the electronic wavefunction, enabling a treatment of nonadiabatic coupling without relying on the adiabatic approximation. This is achieved by explicitly representing the full nuclear wavefunction, avoiding the need to calculate coupling terms as perturbations and allowing for accurate simulations of dynamics where multiple electronic states significantly contribute to the overall evolution of the system.

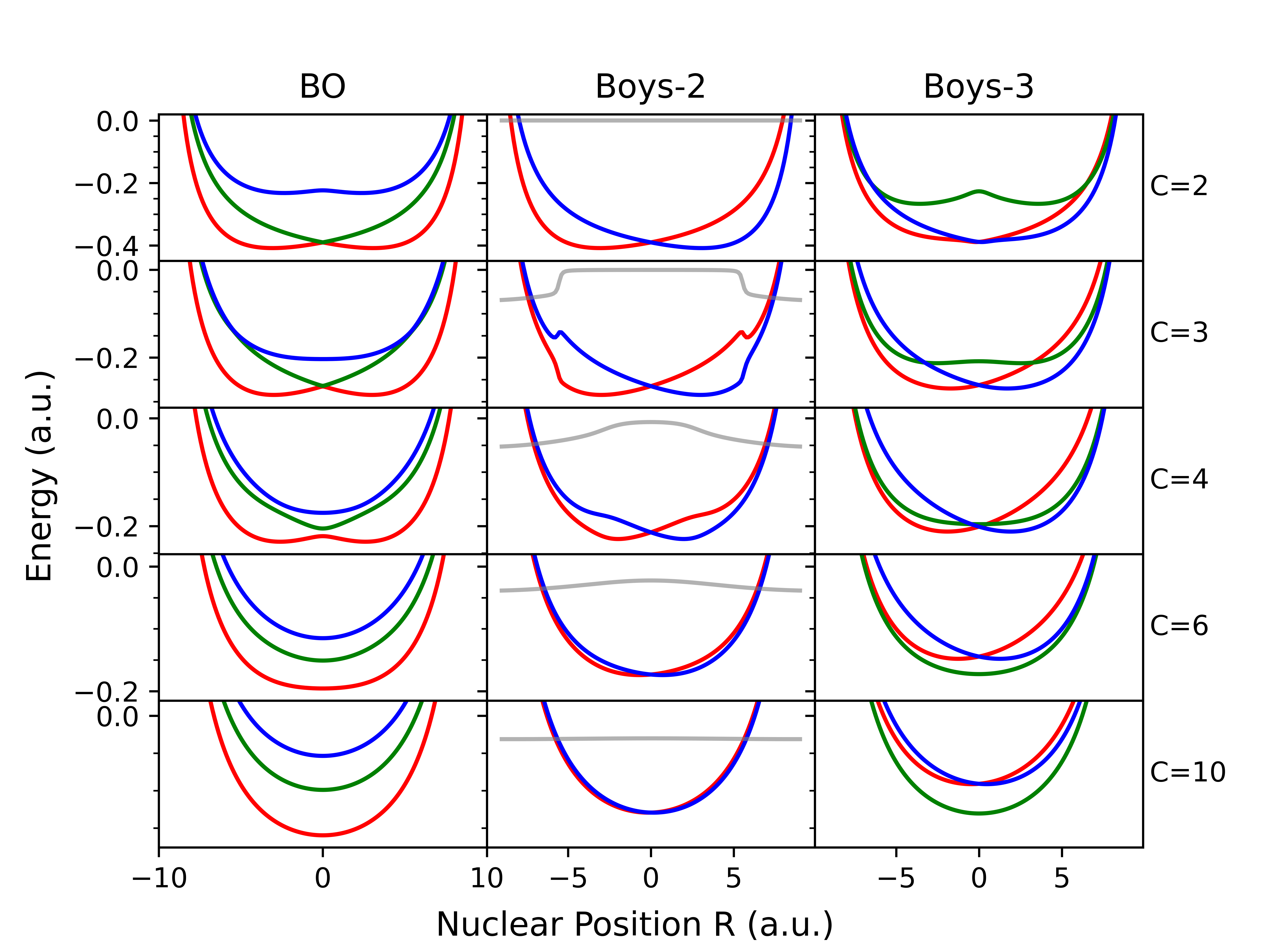

Diabatic representations are central to Phase Space Electronic Structure by providing a basis set designed to minimize the electronic coupling between states. These representations are frequently constructed using Boys Localization, a procedure that mathematically isolates electronic wavefunctions into spatially distinct regions. This localization effectively reduces the off-diagonal matrix elements in the Hamiltonian, simplifying the calculation of nonadiabatic dynamics. By minimizing coupling, the diabatic approach allows for a more efficient and accurate treatment of systems where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down, as it reduces the computational cost associated with explicitly treating couplings between potential energy surfaces. The resulting Hamiltonian is thus more amenable to time propagation and the simulation of coupled electronic and nuclear motion.

From Simplifications to Reality: Modeling Electron Transfer with Increasing Fidelity

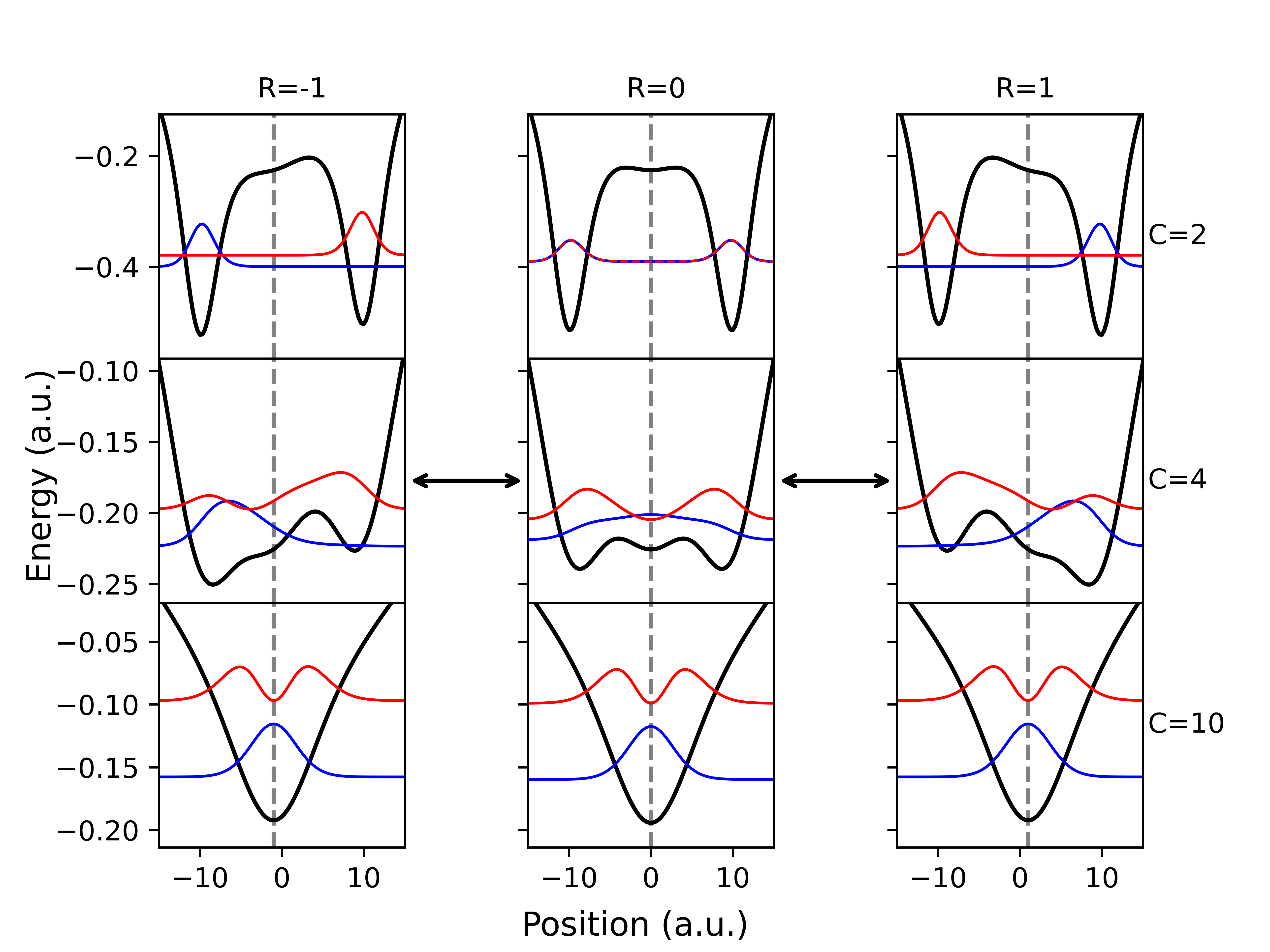

The Shin-Metiu model represents an early approach to simulating electron transfer reactions, simplifying the system to a one-dimensional potential energy surface. This simplification allows for analytical treatment and provides initial insights into the key parameters governing electron transfer rates. Critically, the model incorporates two essential concepts: reorganization energy, λ, which quantifies the energy required for nuclear rearrangement during electron transfer, and nonadiabatic coupling, V, representing the interaction between electronic and nuclear degrees of freedom. These parameters directly influence the probability of electron transfer and are central to understanding the dynamics of the reaction. While limited in its scope, the Shin-Metiu model serves as a foundational framework for more complex and realistic simulations.

The Spin-Boson model extends electron transfer theory beyond the simplified assumptions of the Shin-Metiu model by explicitly incorporating the effects of the surrounding environment as a collection of harmonic oscillators. This environment induces fluctuations in the energy levels of both the donor and acceptor states, influencing the electron transfer rate and requiring treatment of the vibrational degrees of freedom. The model represents the environmental vibrations as a continuous spectrum, characterized by a spectral density J(\omega) and a reorganization energy λ quantifying the energy required to adjust the nuclear coordinates to accommodate the change in electronic state. Accurate representation of these environmental factors is crucial for predicting electron transfer dynamics in complex systems, especially when the electronic and vibrational energy scales become comparable, leading to the partially nonadiabatic regime.

The Phase Space Electronic Structure (PESES) framework, when used with models such as Shin-Metiu and Spin-Boson, facilitates quantitative predictions of electron transfer rates. Specifically, this work demonstrates that PESES implementation achieves up to two orders of magnitude improvement in vibrational energy gap accuracy compared to traditional Born-Huang diabatization methods. This enhanced accuracy is observed within the partially nonadiabatic regime, defined here as coupling strength C values between 4 and 8 atomic units. The improved precision is critical for accurately modeling electron transfer dynamics in complex chemical systems and provides a more reliable basis for comparison with experimental data.

Chirality’s Subtle Influence: How Geometry Dictates Spin Selectivity

Chiral Induced Spin Selectivity (CISS) arises from a fundamental interplay between the movement of electrons and the nuclei within chiral molecules, a connection best described by Phase Space Electronic Structure. This theoretical framework moves beyond traditional approaches by explicitly considering the correlations between electronic and nuclear motion, revealing how a molecule’s three-dimensional shape dictates electron spin. Instead of treating electrons and nuclei as independent entities, Phase Space Electronic Structure maps their combined dynamics, demonstrating that the chiral environment induces a coupling that preferentially scatters electrons with a specific spin orientation. This isn’t simply a surface phenomenon; the entire molecular geometry contributes to the spin polarization, influencing processes ranging from electron transmission through molecules to the efficiency of asymmetric catalytic reactions. The ability to accurately model these vibronic couplings is, therefore, essential for both understanding and ultimately harnessing CISS in advanced materials and chemical applications.

The Berry phase, a geometric effect arising from the adiabatic evolution of electrons within chiral molecules, dictates the spin polarization of transferred electrons. As an electron traverses a chiral environment – one that is non-superimposable on its mirror image – its wavefunction undergoes a phase shift not attributable to external electromagnetic fields, but rather to the shape of the potential energy surface itself. This accumulated geometric phase alters the electron’s spin, favoring either spin-up or spin-down transfer depending on the chirality of the molecule. Effectively, the molecule acts as a spin filter, with the transferred electron’s spin becoming entangled with the chiral structure. This phenomenon, crucial to understanding Chiral Induced Spin Selectivity (CISS), has profound implications for developing novel spintronic devices and highly efficient asymmetric catalysts, where controlling electron spin is paramount.

Chiral molecules, lacking mirror symmetry, possess a remarkable ability to influence the spin of electrons during chemical reactions and material interactions. This phenomenon, known as Chiral Induced Spin Selectivity (CISS), arises because the three-dimensional structure of these molecules dictates a preferential pathway for electron transfer, favoring one spin state over another. Consequently, chiral molecules can act as efficient spin filters, potentially revolutionizing spintronic devices by enabling the creation of materials with tailored spin currents. Beyond electronics, this spin selectivity has profound implications for asymmetric catalysis, where chiral molecules guide reactions to produce single enantiomers of desired products – a crucial process in pharmaceutical development and fine chemical synthesis. The ability to control electron spin with molecular chirality opens avenues for designing highly efficient and selective catalysts, minimizing waste and maximizing product purity.

The pursuit of increasingly sophisticated models for electron transfer-this phase space electronic structure framework, for instance-feels perpetually destined to become tomorrow’s legacy code. The article champions a more accurate subspace of diabatic states, accounting for nuclear and electronic momentum, but one anticipates production environments will inevitably unearth edge cases that expose unforeseen complexities. As the authors refine their approach to nonadiabaticity and vibrational energy gaps, it’s a safe bet that something, somewhere, will break the elegant theory. It brings to mind a sentiment expressed by Albert Einstein: ‘The only thing that you absolutely have to know, is the location of the button.’ A beautifully precise model is useless if it can’t handle the messy reality of a system under stress.

Where Does This Leave Us?

The presented phase space framework offers a refinement in describing electron transfer, admittedly a problem that has seen countless ‘elegant solutions’ over the decades. It neatly sidesteps some limitations of the Born-Huang approach by explicitly incorporating momentum, a detail often glossed over until production data reveals its inconvenient prominence. One suspects, however, that this increased dimensionality will introduce new challenges in practical calculations – the devil, as always, residing in the scaling. The promise of a ‘more accurate subspace’ feels familiar; it echoes countless prior claims, each eventually succumbing to the realities of complex systems.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on extending this framework to multi-electron systems and incorporating environmental effects. The authors rightly point to the need for efficient algorithms; a concern that, given experience, suggests a forthcoming explosion of approximation techniques. The true test won’t be whether the theory can describe the system, but whether it can do so without requiring a supercomputer the size of a small country.

Ultimately, this work is a step towards a more complete description, but it’s a reminder that the pursuit of perfect models is a Sisyphean task. The goalposts invariably shift, and what appears as a breakthrough today will likely become a baseline for the next generation of approximations. If all simulations validate the theory, it simply means the tests are not probing the interesting edge cases.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16209.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- The 10 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Enterprise

2026-01-25 02:27