Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research forecasts the potential to detect subtle distortions in gravitational waves caused by the existence of massive spin-2 fields, offering a pathway to test alternatives to general relativity.

This study investigates the detectability of massive gravity effects on gravitational wave propagation using current and future detectors, including LIGO, the Einstein Telescope, and LISA.

While General Relativity successfully describes gravity, extensions incorporating massive spin-2 fields offer potential resolutions to fundamental cosmological puzzles. This work, ‘Effects of massive spin-2 fields on gravitational wave propagation’, investigates the observational consequences of these fields on gravitational wave propagation, deriving an analytical transfer function to characterize waveform modifications in the ultrarelativistic regime. Establishing detectability bounds, we forecast accessible parameter space using current and future detectors like LIGO, Einstein Telescope, and LISA. Could forthcoming gravitational wave observations ultimately reveal evidence for these beyond-Einsteinian gravitational degrees of freedom?

Chasing Shadows: The Allure of a Massive Graviton

Despite its enduring success in describing gravity, General Relativity encounters fundamental limitations when attempting to incorporate a mass for the graviton – the hypothetical particle mediating gravitational force. Current formulations predict the graviton to be massless, a cornerstone of the theory’s mathematical consistency and observed long-range behavior of gravity. Introducing mass fundamentally alters the theory’s predictions, potentially resolving cosmological discrepancies and offering new insights into the universe’s expansion. However, this seemingly straightforward modification presents significant theoretical hurdles; simply adding a mass term to the equations leads to inconsistencies, disrupting the well-established framework and necessitating the development of entirely new approaches to reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics. The pursuit of a consistent theory of massive gravity, therefore, represents a major frontier in theoretical physics, pushing the boundaries of established knowledge and demanding innovative mathematical techniques.

The proposition of a massive graviton-a carrier of the gravitational force possessing inherent mass-holds the potential to resolve longstanding cosmological challenges and reshape predictions concerning gravitational interactions. Current models, like General Relativity, assume a massless graviton, but introducing mass could provide a natural explanation for the observed accelerated expansion of the universe, potentially eliminating the need for dark energy. Furthermore, a massive graviton fundamentally alters the range of gravitational influence; instead of extending infinitely, gravity would diminish exponentially with distance, impacting the dynamics of black holes and the large-scale structure of the cosmos. This modification also influences the predicted speed of gravitational waves, potentially offering a means to test the theory through precise astronomical observations and gravitational wave detectors, and could address inconsistencies between theoretical predictions and observations regarding the behavior of gravity at cosmological scales.

Early efforts to construct theories of massive gravity encountered significant hurdles, most notably the Boulware-Deser ghost and the Van Dam-Veltman-Zakharov (VdVZ) discontinuity. The Boulware-Deser ghost manifests as a particle with negative kinetic energy, violating fundamental principles of quantum field theory and rendering the theory unstable. Simultaneously, the VdVZ discontinuity predicted that, unless carefully managed, giving the graviton mass would lead to long-range gravitational forces differing drastically from those predicted by General Relativity – specifically, a force that doesn’t diminish with distance, creating inconsistencies with observed astrophysical phenomena. These issues demonstrated that simply adding a mass term to the Einstein-Hilbert action – the foundation of General Relativity – isn’t a viable path toward a consistent theory of massive gravity, necessitating more sophisticated approaches to circumvent these problematic predictions.

dRGT: A Kludge That Might Just Work

The dRGT model addresses the Boulware-Deser (BD) ghost, a problematic feature arising in linear massive gravity theories, through a non-linear completion of the theory. Linearized massive gravity introduces a massive spin-2 field – the graviton – by adding a mass term \frac{1}{2} m^2 h_{\mu\nu} h^{\mu\nu} to the Einstein-Hilbert action. This leads to the appearance of a BD ghost – an unphysical, negative-kinetic-energy scalar degree of freedom. The dRGT construction avoids this issue by strongly coupling the massive graviton to a scalar field and introducing additional degrees of freedom, effectively “eating” the ghost. This is achieved through a specific metric formulation that allows for a consistent, ghost-free propagation of the massive spin-2 field, thus providing a viable framework for massive gravity beyond the linear approximation.

The dRGT model constructs a metric tensor, \hat{g}_{\mu\nu} , as a function of a fiducial metric, f_{\mu\nu} , and a dynamically generated metric, h_{\mu\nu} . This formulation allows for the inclusion of the Fierz-Pauli mass term, m^2 h_{\mu\nu} , directly into the gravitational action. The Fierz-Pauli term introduces mass to the graviton by adding a kinetic term proportional to the square of the metric perturbation, h_{\mu\nu} , effectively modifying the graviton propagator and giving the particle a finite mass. This contrasts with standard General Relativity where the graviton is massless. The specific construction of \hat{g}_{\mu\nu} is crucial to avoid the Boulware-Deser ghost, which arises in simpler attempts to introduce mass to gravity.

The Vainshtein mechanism within the dRGT model addresses the issue of strong coupling in massive gravity theories. As the graviton acquires mass, interactions become strongly coupled at energy scales below the mass, leading to inconsistencies with observed physics. The Vainshtein mechanism mitigates this by introducing a non-linear screening effect; the extra scalar degrees of freedom present in dRGT generate a self-interaction that effectively screens the massive graviton’s influence at low energies and large distances. This screening ensures that the theory remains weakly coupled and consistent with experimental constraints derived from solar system tests and cosmological observations, effectively hiding the massive graviton’s effects from these measurements.

Gravitational Waves: A Glimmer of Hope for Detection

Massive gravity theories posit that the graviton, the quantum of gravitational interaction, possesses a non-zero mass. This contrasts with General Relativity, which assumes a massless graviton. A consequence of a massive graviton is the existence of massive tensor modes in gravitational waves, alongside the standard massless modes. These massive modes exhibit an exponential decay with distance, limiting their detectability to relatively nearby sources. Furthermore, the presence of these additional modes alters the polarization content of gravitational waves, introducing longitudinal modes not present in General Relativity. The propagation speed of these massive modes is also reduced compared to the speed of light, leading to potential time delays and waveform distortions detectable by gravitational wave observatories. The mass of the graviton, m_g , directly influences the Compton wavelength of the graviton, \lambda_g = h / (m_g c) , and therefore the scale at which these modifications become significant in gravitational wave observations.

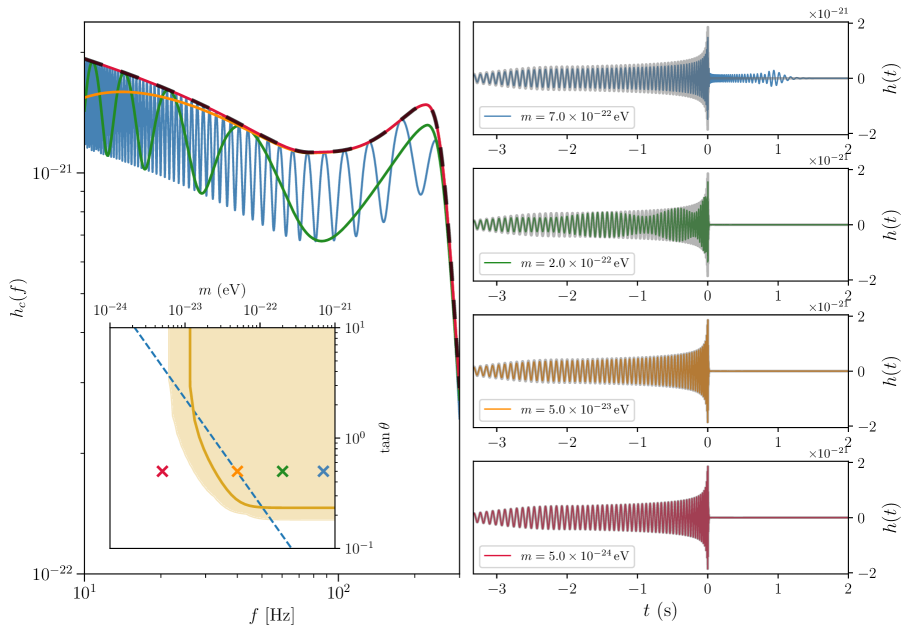

Modifications to gravitational wave propagation predicted by massive gravity theories manifest as alterations to the observed waveform, with the most significant effects concentrated at lower frequencies. This frequency dependence arises because the effects of graviton mass become more pronounced as the wavelength of the gravitational wave increases. Current ground-based detectors, such as LIGO and Virgo, and future space-based observatories like LISA, are sensitive to different frequency ranges, allowing for complementary searches for these waveform deviations. Analyses focus on subtle changes to parameters like the chirp mass, luminosity distance, and polarization, which would indicate a departure from the predictions of General Relativity. The ability to detect these modifications is contingent on the sensitivity of these observatories and the actual mass of the graviton; lower graviton masses generally produce more detectable effects at observable frequencies.

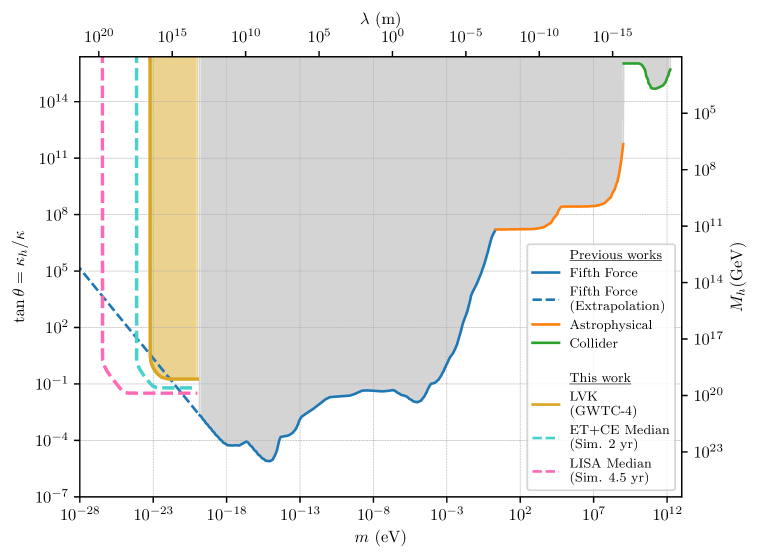

Recent analytical forecasts indicate that current gravitational wave observations are capable of refining existing upper limits on the graviton mass, specifically for masses below 10^{-{20}} eV. These constraints are derived from analyzing the potential modifications to gravitational wave propagation caused by massive gravity theories. By precisely measuring waveform characteristics and comparing them to predictions from General Relativity, current detector networks-including LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA-can place tighter bounds on the graviton mass. Future observatories, such as the Einstein Telescope and Cosmic Explorer, are projected to further improve these constraints, potentially reaching sensitivities capable of detecting or excluding graviton masses within this range.

The Lindblom distinguishability criterion establishes a quantitative method for assessing deviations in observed gravitational waveforms from those predicted by General Relativity, specifically in the context of massive gravity theories. This criterion relies on comparing the difference between the waveforms generated by General Relativity and those predicted by massive gravity models, normalized by the signal-to-noise ratio. Current analyses, utilizing this criterion, demonstrate the potential to detect or exclude graviton masses below 10^{-{20}} eV, based on the sensitivity of current and planned gravitational wave detectors. The criterion effectively provides a threshold for distinguishing between General Relativity and massive gravity based on waveform characteristics, with detectability directly correlated to the precision of waveform measurements and detector sensitivity.

The Next Generation: Bigger Detectors, More Data, and the Same Fundamental Problems

Existing gravitational wave observatories, including LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA, have revolutionized astronomy by directly detecting ripples in spacetime, as evidenced by the growing Gravitational Wave Transient Catalog 4 (GWTC-4). However, these ground-based detectors are most sensitive to higher-frequency gravitational waves, limiting their ability to observe signals from some of the most massive and distant events in the universe. Lower-frequency waves, often emitted by supermassive black hole mergers or exotic compact objects, require detectors capable of sensing longer wavelengths-a challenge for current instruments due to their size and sensitivity limitations. While the GWTC-4 catalog continues to expand our understanding of stellar-mass black holes and neutron stars, a significant portion of the gravitational wave universe remains hidden from these first-generation observatories, motivating the development of next-generation detectors designed to bridge this crucial gap in observational capability.

Next-generation gravitational wave observatories promise a revolutionary expansion of humanity’s cosmic reach. Projects like the ground-based Einstein Telescope and Cosmic Explorer, alongside the space-based LISA mission, are designed to detect gravitational waves across a broader frequency spectrum than currently possible. This expanded sensitivity is crucial for observing signals from previously inaccessible sources, particularly those involving massive gravity – events like the mergers of supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies, or the early universe’s primordial gravitational waves. By pushing the boundaries of detection, these observatories will not only confirm predictions of general relativity in extreme environments, but also offer a new window into the formation and evolution of the universe, revealing details about cosmic structures and processes hidden from traditional electromagnetic observation. This improved capacity to detect low-frequency signals will enable a deeper understanding of the population of stellar-mass black holes and their influence on galactic evolution.

Anticipating the wealth of data from future gravitational wave detectors necessitates proactive development of analysis tools. Researchers are leveraging resources like the gwtoolbox Library, a comprehensive Python package designed for gravitational wave data analysis, in conjunction with the Box-Like Detector Approximation. This approximation simplifies complex detector responses, allowing for rapid, analytical estimates of signal detectability and parameter estimation biases. By combining these computational resources with simplified modeling techniques, scientists can effectively forecast detector performance, optimize data processing pipelines, and establish lower bounds on the accessible parameter space – ultimately preparing for the challenges and opportunities presented by the next generation of gravitational wave detectors and ensuring robust analysis of the expected increase in observed events.

Predicting the capabilities of future gravitational wave detectors relies on establishing fundamental limits to what can be observed, and analytical forecasts provide a crucial framework for understanding these boundaries. Detectability isn’t simply a matter of increased sensitivity; it’s intrinsically linked to a characteristic mass scale, mathematically defined as \sqrt{H_0 <i> 2π </i> f_c / α}. Here, H_0 represents the Hubble constant, defining the universe’s expansion rate, while f_c denotes the detector’s low-frequency cutoff-the lowest frequency it can reliably measure. The parameter α encapsulates detector-specific noise properties. This mass scale essentially sets a lower bound on the masses of objects detectable through gravitational waves; signals from objects with masses significantly below this threshold are likely to be lost in the noise. Consequently, understanding and refining this characteristic mass scale is paramount for optimizing detector design and focusing observational strategies on the most promising regions of the parameter space, ultimately maximizing the scientific return from these next-generation observatories.

The pursuit of modified gravity, as detailed in this exploration of massive spin-2 fields and their effect on gravitational wave propagation, feels predictably Sisyphean. Researchers meticulously calculate waveform transfer functions and detectability forecasts for detectors like LIGO and LISA, striving for precision in a universe that delights in introducing noise. It’s a noble effort, yet one cannot help but recall Sartre’s words: “Hell is other people’s theories.” Each elegant model, each hopeful prediction, becomes a potential source of future discrepancies when confronted with actual production data. The Lindblom criterion, a seemingly solid foundation, will inevitably reveal its limitations. It’s not cynicism, merely acknowledging that if code-or in this case, a cosmological model-looks perfect, no one has deployed it yet.

What’s Next?

The exercise of forecasting detectability limits for modified gravity-in this instance, massive spin-2 fields-inevitably arrives at a familiar impasse. Improved detectors, larger datasets, and increasingly sophisticated signal processing will undoubtedly shrink those limits. However, the underlying assumption-that deviations from general relativity will manifest as subtle waveform distortions amenable to current analytical techniques-remains largely untested. The field seems perpetually poised to confirm or refute these models, yet the signal continues to hide within the noise, or perhaps, within the limitations of the models themselves.

Future work will likely focus on refining the waveform transfer functions used in these forecasts, incorporating more complex field dynamics, and exploring alternative search strategies. Yet, a critical question remains unaddressed: how much of this effort represents genuine progress, and how much is simply the reinvention of signal processing crutches? The Lindblom criterion, while useful, is ultimately an approximation, and the true behavior of these fields in strong gravitational regimes may well invalidate its assumptions.

The pursuit of modified gravity is not necessarily a search for ‘new physics’, but a continuous exercise in stress-testing the elegance of existing frameworks. The expectation isn’t to find deviation, but to rigorously define the boundary conditions under which general relativity fails. Perhaps, in the long run, the most valuable outcome will not be a detection, but a more precise understanding of just how resilient-or fragile-our current understanding of gravity truly is.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15201.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- Gold Rate Forecast

- PS5, PS4’s Vengeance Edition Helps Shin Megami Tensei 5 Reach 2 Million Sales

- The 10 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Enterprise

- How to Build a Waterfall in Enshrouded

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

2026-01-22 22:24