Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research utilizes observations of neutron stars to test alternative theories of gravity, specifically exploring the viability of f(Q) gravity.

Bayesian analysis of NICER data constrains the functional form of f(Q), favoring an exponential model for nonmetricity-based modified gravity.

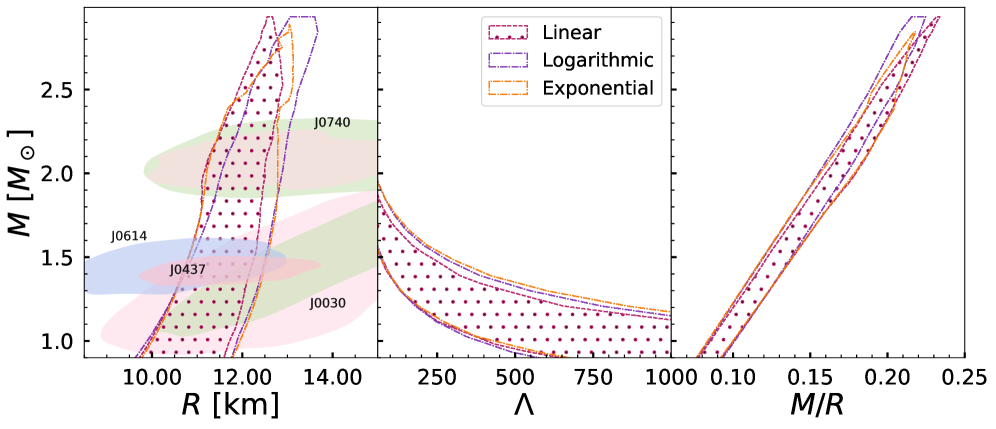

The persistent challenge of reconciling general relativity with observations of extreme gravitational environments motivates exploration beyond Einstein’s theory. This is addressed in ‘Bayesian Inference of Neutron Star Properties in $f(Q)$ Gravity Using NICER Observations’, which investigates neutron stars within the framework of symmetric teleparallel $f(Q)$ gravity by performing Bayesian inference on data from the NICER mission. Results demonstrate that an exponential functional form for $f(Q)$ is statistically preferred, yielding a radius of R_{1.4} = 11.27^{+0.53}_{-0.36}\,\mathrm{km} at a mass of 1.4\,M_\odot. Do these findings suggest neutron stars can serve as uniquely sensitive probes of modified gravity in the strong-field regime, potentially revealing deviations from general relativity?

The Relentless Pursuit of Gravity’s Limits

Despite its enduring success in describing gravity, General Relativity encounters fundamental difficulties when applied to scenarios involving extreme gravitational fields. These challenges arise from the theory’s incompatibility with quantum mechanics, suggesting a breakdown of predictability at the singularity within black holes and potentially even within the incredibly dense cores of neutron stars. Furthermore, General Relativity predicts the existence of naked singularities – points where gravity is infinitely strong and not shielded by an event horizon – which, if they exist, would violate the cosmic censorship hypothesis and necessitate a revised understanding of spacetime. Consequently, physicists are actively investigating modifications to Einstein’s theory, exploring alternative gravitational frameworks that could resolve these theoretical inconsistencies and accurately describe gravity under the most extreme conditions. These investigations aren’t merely academic; a more complete theory of gravity is crucial for understanding the universe’s origins, the fate of massive stars, and the behavior of matter at its densest states.

Neutron stars represent an unparalleled astrophysical setting for rigorously testing the foundations of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. These stellar remnants, created from the gravitational collapse of massive stars, pack more mass than the Sun into a sphere roughly the size of a city. This extreme density generates incredibly strong gravitational fields – conditions far exceeding anything achievable on Earth or observed in most other cosmic phenomena. By meticulously observing neutron stars and analyzing their behavior-such as the orbits of binary systems or the timing of pulsars-scientists can probe how gravity operates in its most intense form. Deviations from the predictions of General Relativity within these systems could signal the need for new physics and a refined understanding of gravity itself, making neutron stars essential tools in the quest to reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics and unravel the mysteries of the universe.

Determining the Mass-Radius Relation for neutron stars is a central challenge in modern astrophysics, demanding both observational breakthroughs and sophisticated theoretical frameworks. This relation, which connects a neutron star’s mass to its radius, reveals crucial information about the matter existing at extreme densities – densities far beyond anything achievable in terrestrial laboratories. Current observations, primarily through measurements of pulsar timing and X-ray bursts, provide constraints on this relationship, but substantial uncertainties remain. Refining these measurements requires increasingly sensitive instruments, such as the next generation of X-ray telescopes, and advanced techniques to account for effects like stellar rotation and strong magnetic fields. Simultaneously, theoretical modeling must grapple with the complexities of the equation of state for matter at these densities, incorporating insights from quantum chromodynamics and nuclear physics. A precise determination of the Mass-Radius Relation not only tests the predictions of General Relativity in the strong-field regime, but also offers a unique window into the fundamental nature of matter itself, potentially revealing exotic phases like quark matter or hyperons within these incredibly dense stellar cores.

Despite the enduring success of General Relativity, current observations of neutron stars do not entirely rule out alternative theories of gravity. The precision with which scientists can determine a neutron star’s mass and radius is still limited, creating a window of uncertainty where deviations from Einstein’s predictions are plausible. This observational ambiguity fuels ongoing research into modified gravity models, exploring possibilities like scalar-tensor theories or those incorporating higher-order curvature terms. These investigations aren’t attempts to disprove General Relativity, but rather to rigorously test its boundaries and explore whether more comprehensive frameworks are needed to fully describe gravity under the extreme conditions found within these incredibly dense celestial objects. The pursuit of ever-more-precise measurements, coupled with advanced theoretical modeling, promises to either solidify General Relativity’s reign or reveal subtle clues pointing towards a new era in gravitational physics.

Beyond Einstein: A Geometric Shift with f(Q) Gravity

f(Q) gravity represents a modification of General Relativity that incorporates nonmetricity as a fundamental aspect of spacetime geometry. In General Relativity, the metric tensor describes the gravitational field and determines distances between points; nonmetricity, mathematically defined as the failure of the connection to be metric-compatible, introduces a geometric property independent of the metric. Specifically, nonmetricity quantifies the change in length of a vector when parallel transported along a closed loop – a phenomenon absent in standard General Relativity where the connection is assumed to be metric-compatible. By constructing gravitational actions as a function of Q, the nonmetricity scalar, f(Q) gravity aims to provide alternative cosmological and astrophysical solutions while potentially avoiding the need for dark matter or dark energy, and differing from theories that introduce extra fields or dimensions.

Many modified gravity theories attempt to resolve cosmological discrepancies with General Relativity by introducing new fields or particles, effectively increasing the number of degrees of freedom in the model. f(Q) gravity presents a distinct approach; it modifies the gravitational action through a function of nonmetricity Q without requiring the addition of novel fields. This characteristic is significant because it avoids potential instabilities and complexities associated with introducing extra degrees of freedom, simplifying the theoretical framework and potentially leading to more predictive cosmological models. Consequently, f(Q) gravity offers a potentially parsimonious solution to outstanding problems in cosmology, such as dark energy and the Hubble tension, without exacerbating existing theoretical challenges.

Specific implementations of f(Q) gravity are determined by the chosen functional form of the nonmetricity scalar Q within the gravitational action. The Linear f(Q) Model defines gravity with a linear relationship between the action and Q, expressed as f(Q) = \alpha Q, where α is a constant. The Logarithmic f(Q) Model utilizes a logarithmic function, such as f(Q) = \beta \log(Q), with β as a constant parameter. Conversely, the Exponential f(Q) Model employs an exponential function, generally represented as f(Q) = \gamma e^{\delta Q}, where γ and δ are constants. Each functional form results in a unique set of field equations and therefore predicts potentially different cosmological and astrophysical behavior.

f(Q) gravity extends General Relativity by incorporating nonmetricity as a dynamical variable describing gravitational interactions. General Relativity relies solely on the metric tensor to define spacetime geometry and gravity; however, nonmetricity, quantified by the nonmetricity tensor Q_{\alpha \mu \nu}, represents the failure of parallel transport of a vector along a closed loop. In f(Q) gravity, the gravitational action is constructed as a function of Q, specifically the trace of the nonmetricity tensor, replacing the Ricci scalar used in the Einstein-Hilbert action. This modification allows for a geometric description of gravity independent of the metric, potentially resolving cosmological challenges without introducing new fields or dimensions beyond those already present in General Relativity.

Modeling the Extremes: Neutron Stars within f(Q) Gravity

The Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equation is the standard model describing the hydrostatic equilibrium of spherically symmetric, relativistic stars, and is fundamentally important for determining neutron star structure. This equation relates the internal spacetime geometry to the energy-momentum tensor of the stellar material. Solving the TOV equation requires an Equation of State (EoS) that connects pressure to energy density; the DDME2 EoS is a commonly used example, representing a density-dependent MDI interaction and providing a realistic description of nuclear matter at the extreme densities found within neutron stars. Combining the TOV equation with a suitable EoS allows for the calculation of key neutron star properties, including mass, radius, and central density, which are essential for understanding their formation, evolution, and stability. \frac{dM}{dr} = 4\pi r^2 \rho(r) represents a simplified form of the TOV equation, highlighting the relationship between the mass M enclosed within radius r and the density \rho(r).

Employing the f(Q) gravity framework for neutron star modeling involves substituting the Ricci scalar, R, in the Einstein-Hilbert action with a function of non-metricity, Q. This modification alters the field equations, specifically the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equation, which governs the hydrostatic equilibrium of spherically symmetric, relativistic stars. Solving the modified TOV equation, alongside an appropriate Equation of State (EoS) – such as DDME2 – yields solutions for the neutron star’s mass and radius as functions of its internal structure. The resulting mass-radius relationship differs from that predicted by General Relativity, and these deviations can be quantified and compared to observational data to constrain the parameters defining the f(Q) function. The precise calculation requires numerical integration of the modified TOV equation, often employing iterative methods to achieve convergence.

Neutron star tidal deformability, quantified by the dimensionless tidal Love number Λ, directly relates to how much a neutron star deviates from a spherical shape under the influence of the tidal forces present during the inspiral phase of a binary neutron star merger. Gravitational wave detectors, such as LIGO and Virgo, are sensitive to these minute deformations, and the observed waveform contains information about both neutron star masses and tidal deformabilities. Accurate theoretical calculations of Λ – which depend on the neutron star’s mass, radius, and internal composition – are therefore essential for precisely determining the parameters of these systems and testing general relativity. Discrepancies between observed gravitational wave signals and predictions based on general relativity could indicate the presence of new physics, potentially revealed through modifications to the neutron star’s equation of state or the gravitational interaction itself.

Bayesian inference facilitates the parameter estimation of f(Q) gravity models by combining prior probabilities with likelihood functions derived from observational data. This process yields posterior probability distributions for model parameters, quantifying the uncertainty in their values. Observational constraints typically include neutron star masses and radii obtained from multi-wavelength astronomy, as well as tidal deformability measurements inferred from gravitational wave signals detected by observatories like LIGO and Virgo. The likelihood function quantifies the agreement between model predictions – such as predicted tidal deformability Λ for a given mass and radius – and the observed data, weighted by the uncertainties in those observations. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are commonly employed to sample from the posterior distribution, enabling robust statistical inference and allowing for the comparison of different f(Q) gravity models based on their Bayesian evidence.

Constraining the Framework: NICER Observations and the Path Forward

Neutron stars, remnants of massive stellar collapse, present unique opportunities to test the foundations of gravity. Their extreme density creates gravitational fields far stronger than those achievable on Earth, making them ideal laboratories for probing alternative theories to Einstein’s general relativity. The Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) mission provides unprecedentedly precise measurements of both neutron star masses and radii – parameters critically sensitive to the underlying theory of gravity. By meticulously mapping the thermal emission from neutron star surfaces, NICER allows scientists to constrain the equation of state of ultra-dense matter and, crucially, to differentiate between predictions made by various gravity models. These observations effectively act as a ‘stress test’ for theories that attempt to modify or extend general relativity, such as f(Q) gravity, by revealing whether their predictions align with the observed properties of these celestial objects. The accuracy of NICER’s data is therefore pivotal in shaping the future of gravitational physics and determining whether Einstein’s theory remains the most accurate description of gravity at its most extreme.

The precision of NASA’s Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) allows for direct comparison between theoretical predictions and observational data, offering a robust method to assess the viability of alternative gravity theories like f(Q). By modeling neutron stars within the framework of different f(Q) formulations – including Exponential, Logarithmic, and Linear models – researchers can generate predictions for observable quantities such as mass and radius. These predictions are then directly compared to the data provided by NICER, enabling a quantitative evaluation of each model’s goodness-of-fit. This comparative approach, utilizing Bayesian analysis, doesn’t simply accept or reject theories, but rather assigns a probability to each based on the evidence, thereby quantifying the support for or against modifications to Einstein’s general relativity.

A recent Bayesian analysis, leveraging data from the Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER), indicates that an Exponential formulation of f(Q) gravity currently provides the most statistically robust description among tested models. This conclusion arises from a comparison of Bayes factors, a quantitative measure of evidence; the Exponential model achieved a value of ln(BF) = -0.35, exceeding that of both the Logarithmic f(Q) model (ln(BF) = -1.28) and a Linear f(Q) variant. These results suggest that, while alternative gravity theories remain viable, the Exponential model offers a slightly better fit to the observed properties of neutron stars, providing a nuanced perspective on potential modifications to Einstein’s general relativity and encouraging further investigation into the nature of gravity at extreme densities.

Distinct predictions regarding neutron star properties emerge from different formulations within f(Q) gravity. Specifically, the Logarithmic model posits a maximum theoretical mass for neutron stars at 2.36 times the mass of the Sun M_{\odot}, a limit potentially testable through observation of the most massive known pulsars. In contrast, the Exponential model diverges in its focus, predicting a tidal deformability of \Lambda_{1.4} = 156.95 for a 1.4 solar mass neutron star. This value, representing the star’s susceptibility to distortion by gravitational tides, provides a complementary avenue for validating or refuting the model through gravitational wave astronomy, as tidal deformability significantly influences the waveform emitted during neutron star mergers. These differing predictions underscore the power of precise astrophysical measurements – like those provided by NICER – to differentiate between modified gravity theories and refine our understanding of extreme gravitational environments.

The meticulous analysis of neutron star observations, particularly those gathered by the NICER mission, is beginning to illuminate the very foundations of gravity itself. Current research doesn’t seek to disprove Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, but rather to explore whether subtle modifications – such as those proposed by f(Q) gravity – might account for unexplained phenomena in the universe. These alternative theories predict deviations in the relationship between a neutron star’s mass and radius, offering a unique observational pathway to test their validity. The findings suggest that while General Relativity remains a robust description, the universe may allow for – and potentially even favor – slight alterations to its framework, hinting at a more complex gravitational landscape than previously understood and opening exciting avenues for future investigation into the fundamental laws governing the cosmos.

The exploration of f(Q) gravity, as detailed in this research, demonstrates a compelling principle: order manifests through interaction, not control. Attempts to dictate gravitational behavior through imposed equations often fall short; instead, allowing the theory to respond to observational data – in this case, from the NICER mission regarding neutron star properties – reveals the most viable models. The exponential form of f(Q), favored by Bayesian inference, didn’t arise from pre-determined design, but emerged as the most statistically probable explanation given the data. As Richard Feynman observed, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.” This study, by letting the data guide the model, embodies that principle, avoiding the self-deception of imposing expectations onto the universe.

What Lies Ahead?

This exploration of neutron star properties within f(Q) gravity, while favoring an exponential functional form, merely scratches the surface of a far larger question: how much of what appears as exotic physics is simply a misreading of the underlying geometric rules? The Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff equation, a cornerstone of this work, remains inherently tied to assumptions about spacetime, and deviations from general relativity, even if statistically favored, do not necessarily imply new physics, but rather a refinement of existing geometric descriptions. The universe rarely offers definitive answers, instead presenting a continuous spectrum of approximations.

Future work will undoubtedly involve more complex equations of state for neutron stars, and a broader range of f(Q) functions-a natural inclination to add complexity. However, the most fruitful path may lie in loosening the constraints imposed by assuming a static, spherically symmetric spacetime. The real universe is dynamic and anisotropic; attempting to model it with overly simplified forms risks obscuring the emergent behaviors that truly govern its evolution. Weak top-down control, in this instance, allows for a richer exploration of possible solutions.

Ultimately, the search for modified gravity is not about finding the correct theory, but about understanding the limits of our current framework. Order doesn’t require architects; it emerges from local interactions. The statistical preference for a particular f(Q) model is a signal, not a destination. It suggests avenues for further investigation, not a final, immutable truth.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16227.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Sunday Rose Kidman Urban Describes Mom Nicole Kidman In Rare Interview

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- Invincible Star Reveals Dream MCU Casting (& It’s A Real Marvel Deep Cut)

2026-01-26 18:58