Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new theory leverages the full spectrum of wave coherence-from its weakest to strongest points-to establish universally optimal limits on observable wave characteristics.

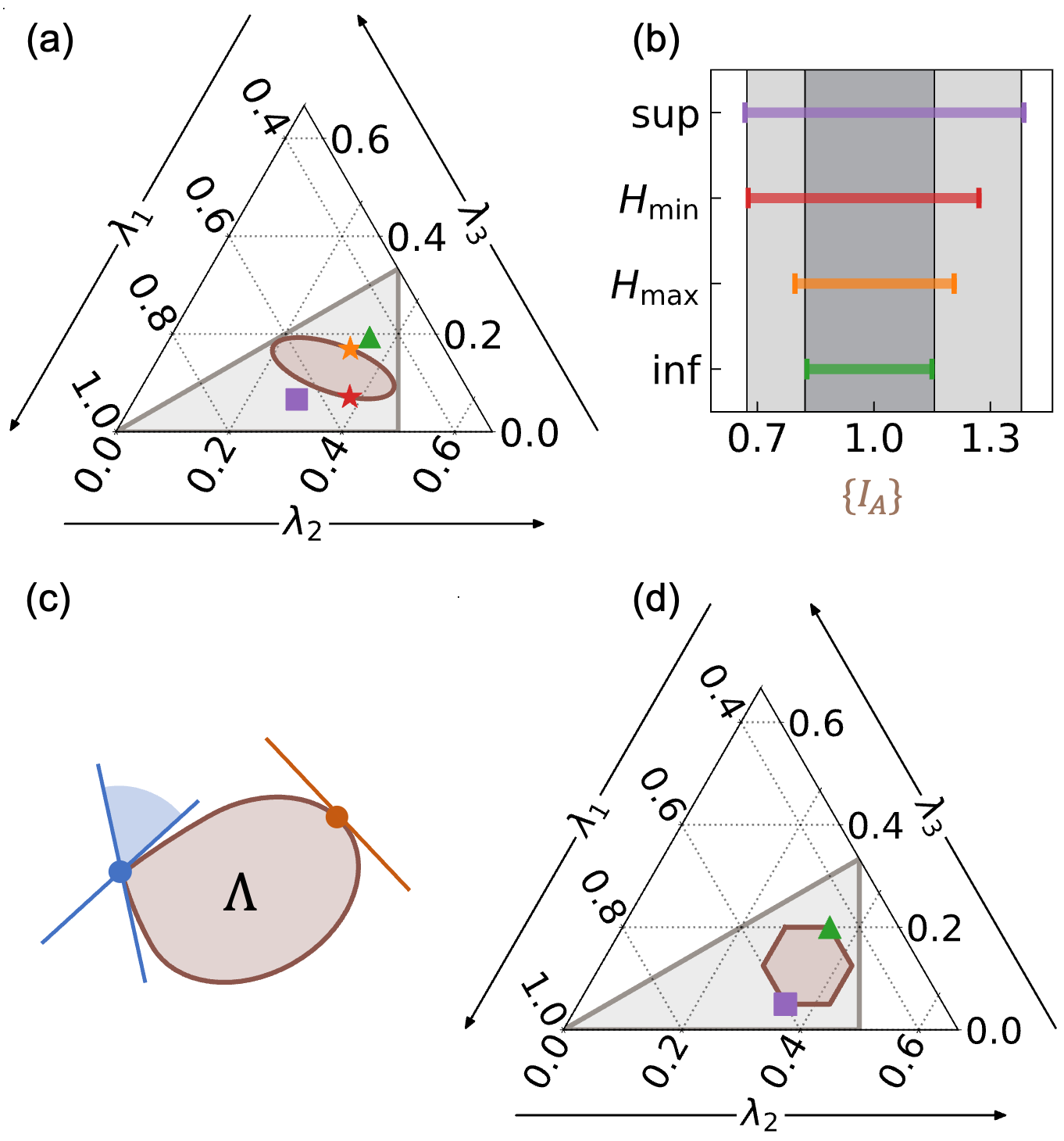

This work demonstrates that optimal bounds for waves with varied coherence are determined by the supremum and infimum of the coherence set, using a majorization-based approach.

Establishing universal limits on wave behavior is often constrained by reliance on extreme values within a given coherence set. This is addressed in ‘Optimal universal bounds for waves with varied coherence based on supremum and infimum coherence spectra’, which introduces a majorization-based theory demonstrating that optimal bounds are, surprisingly, determined not by the maximum and minimum coherence, but by the supremum and infimum of the entire coherence spectrum. The paper details an algorithm for computing these limits, proving they reside at singular points or strictly outside the measured set. Could this approach redefine how we characterize and predict wave phenomena across diverse applications?

The Fragile Dance of Coherence: Defining the Limits of Predictability

Characterizing coherence is central to understanding how waves behave, yet traditional methods often fall short when applied to intricate systems. While simplified models can effectively describe wave propagation in idealized scenarios, real-world phenomena frequently involve waves interacting with heterogeneous media or exhibiting complex spatial and temporal profiles. These complexities introduce correlations between different points in the wave, defining its coherence, which are difficult to capture with conventional techniques relying on scalar approximations or limited sampling. Consequently, predicting the full response of a system-whether it’s light scattering from a rough surface, acoustic transmission through a disordered material, or the behavior of quantum waves-requires more sophisticated approaches capable of accurately quantifying and modeling these intricate coherence properties, pushing the boundaries of current analytical and computational methods.

The behavior of waves, from light and sound to water ripples, is often understood through the concept of a wavefront – the leading edge indicating the wave’s propagation. However, accurately predicting a wave’s ultimate form and intensity isn’t simply a matter of tracking this surface; it demands a comprehensive understanding of the wave’s coherence. Coherence describes the predictable relationship between different points on a wavefront, and its loss – due to scattering, absorption, or complex interactions – fundamentally limits predictive power. While the wavefront provides a geometric description of direction, detailed coherence information, including phase and amplitude correlations, is essential for modeling how the wave will evolve, especially in intricate environments. Without quantifying coherence, even knowing the initial wavefront provides only a partial picture, leaving accurate forecasting of wave behavior impossible in all but the simplest scenarios.

A comprehensive understanding of wave phenomena demands not just describing what waves do, but establishing the precise limits of their potential behavior. Researchers are developing a framework to rigorously delineate these boundaries, leveraging the inherent coherence properties of the wave itself. This approach moves beyond simply characterizing coherence-a measure of the wave’s predictability-to quantifying the achievable response given specific coherence constraints. By mathematically defining these limits, scientists can accurately predict how a wave will propagate and interact with complex systems, even when complete knowledge of the system is unavailable. This has implications for fields ranging from optical imaging, where resolution is fundamentally tied to coherence, to radar systems, where signal clarity depends on maintaining wave predictability, and even quantum mechanics, where wave-particle duality requires a precise understanding of coherence boundaries to interpret experimental results.

Defining the Boundaries of Possibility: The Coherence Spectrum

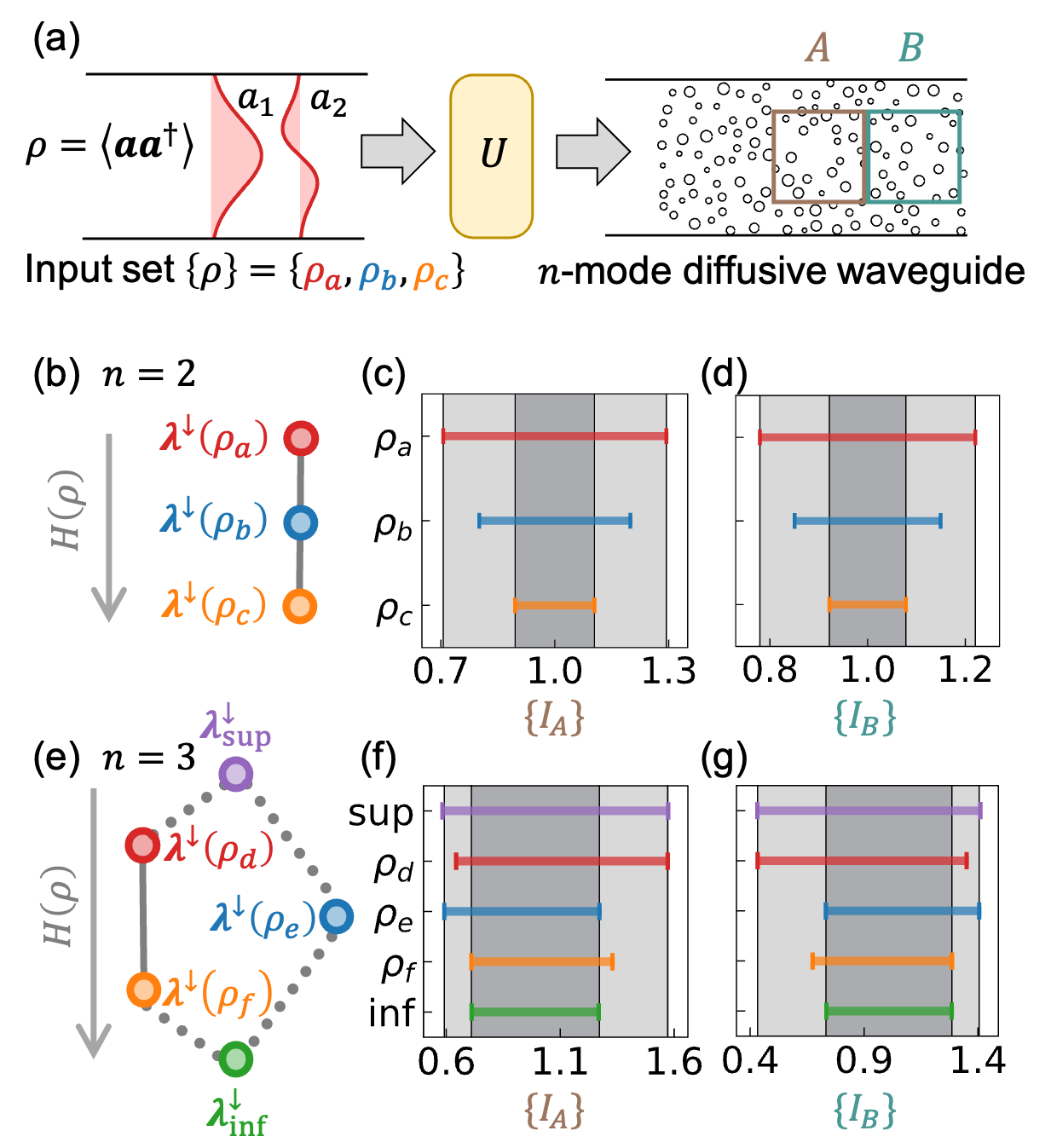

A CoherenceSpectrum, denoted as S(\omega), fully characterizes the coherence properties of a wave by representing the distribution of its spectral density as a function of frequency ω. This spectrum provides a complete description of the wave’s ability to interfere with itself, quantifying the correlation between different points in the wave’s propagation. Crucially, it encapsulates all information necessary to determine the wave’s behavior in various scenarios, forming the analytical basis for subsequent calculations regarding signal limits and observable ranges. The spectrum’s values directly relate to the amplitude and phase relationships within the wave, allowing for precise prediction of interference patterns and signal characteristics.

InnerBound and OuterBound represent the theoretical limits of any measurable response within a system, directly constrained by its coherence spectrum. The InnerBound defines the minimum possible response value, established by the lowest amplitude present within the coherence spectrum, and represents a lower bound on all achievable signals. Conversely, the OuterBound indicates the maximum attainable response, determined by the highest amplitude within the coherence spectrum, and functions as an upper bound. These boundaries are not absolute physical limitations, but rather mathematical constraints derived from the wave’s inherent coherence properties, effectively defining the range within which all observable responses must fall.

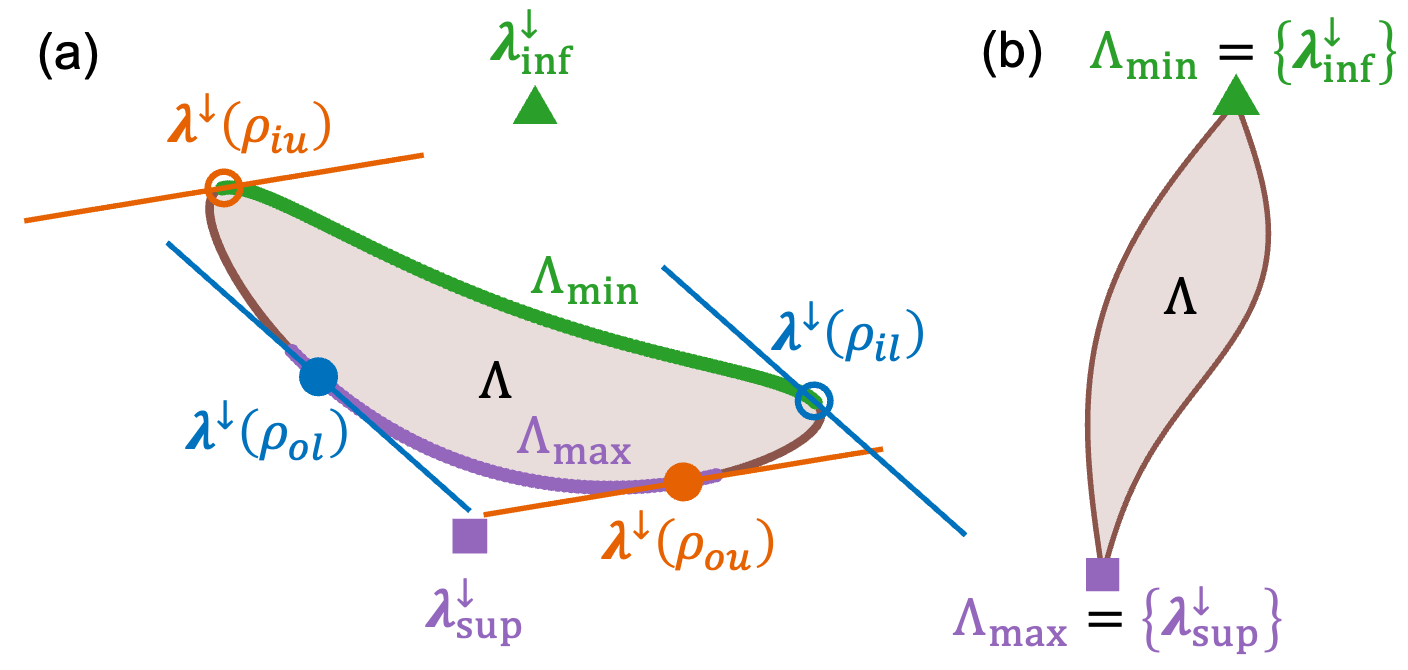

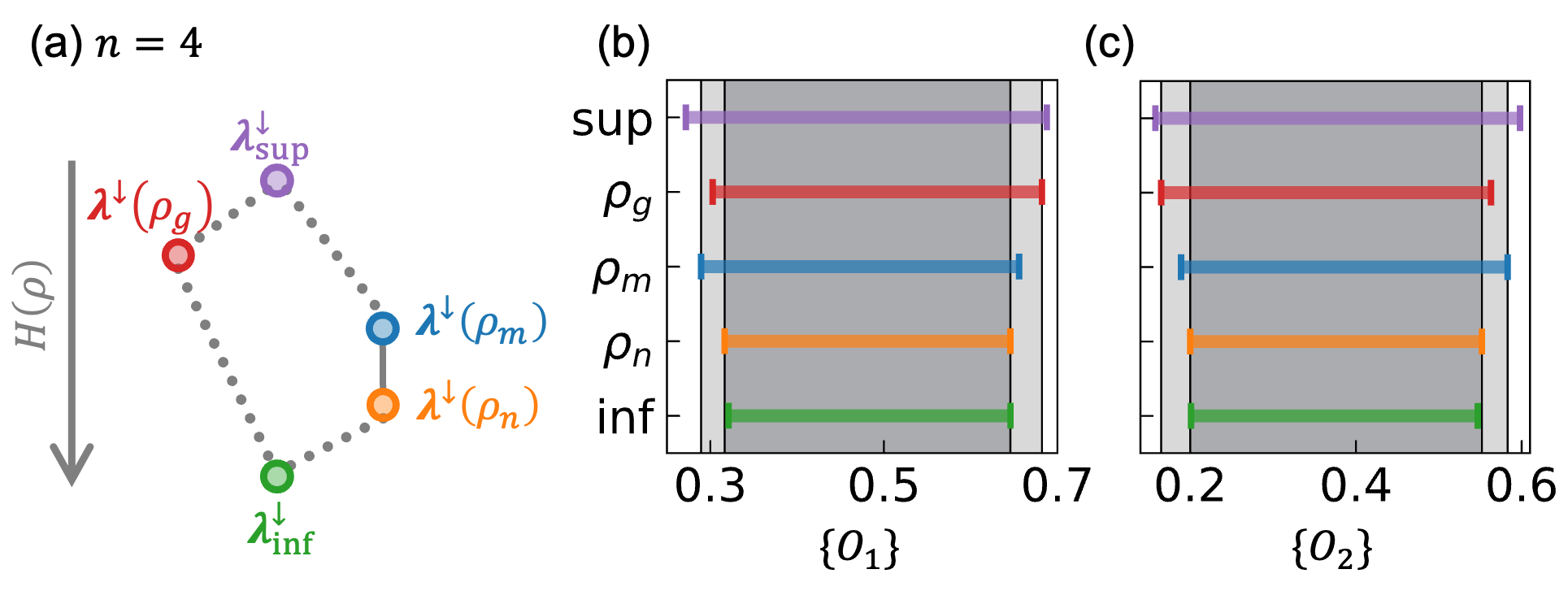

The limits of any observable response are rigorously defined through the mathematical concepts of infimum and supremum applied to the coherence spectrum. The infimum represents the greatest lower bound – the largest value that the response cannot fall below – formally expressed as \in f(R) . Conversely, the supremum defines the least upper bound – the smallest value the response cannot exceed – represented as \sup(R) . This application of infimum and supremum establishes a majorization-based theory, allowing precise bounding of the observable range of responses based solely on the properties of the coherence spectrum, independent of the specific system under analysis. Consequently, any measured response will necessarily fall within the interval defined by these bounds: \in f(R) \leq R \leq \sup(R) .

Ordering the Predictable: Majorization and the Landscape of Coherence

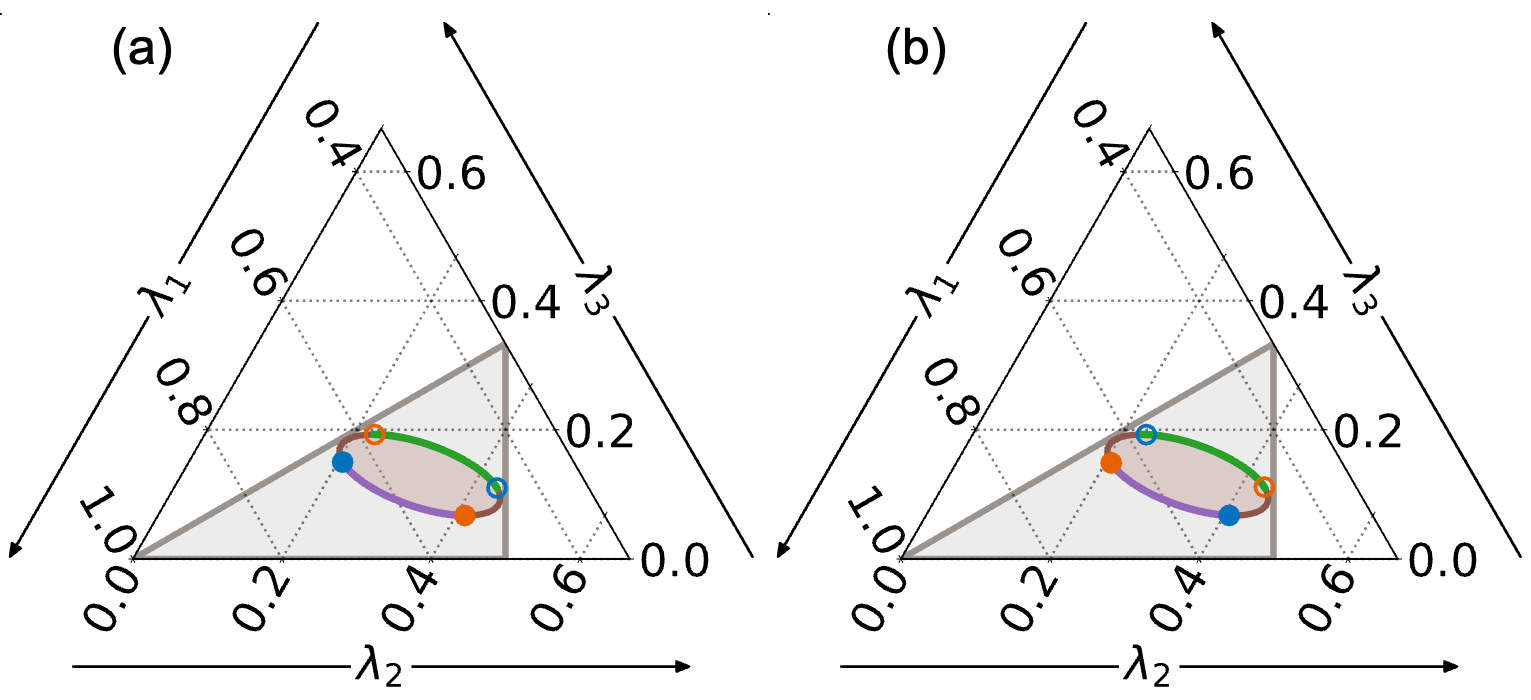

The ‘MajorizationOrder’ method establishes a comparative framework for coherence spectra based on the principle of majorization. This involves assessing whether one spectrum can be obtained from another through a series of partial sums of probabilities, effectively defining a hierarchical relationship between achievable system responses. Specifically, if spectrum A majorizes spectrum B, it indicates that A represents a more coherent state, implying a restricted set of possible outcomes compared to B. The method quantifies this relationship, allowing for the determination of which coherence spectra are attainable given a specific baseline coherence, and provides a rigorous basis for understanding constraints on system behavior imposed by coherence properties.

A Hasse diagram provides a visual representation of the ‘MajorizationOrder’ by depicting the partial order relation between coherence spectra. In this diagram, nodes represent distinct coherence states, and directed edges indicate that one state is ‘majorized’ by another – meaning it represents a more coherent possibility. The diagram’s hierarchical structure clarifies how constraints on coherence limit the achievable response possibilities; a state higher in the diagram can be reached from a lower state through valid transformations, but the reverse is not necessarily true. This visualization aids in understanding which coherence states are accessible given a particular initial condition and the imposed constraints, effectively mapping the space of possible responses based on coherence levels.

The ‘LinearCombination’ function enables the construction of complex coherence spectra from simpler, foundational spectra by calculating convex combinations of their constituent probability distributions. This process adheres to the established majorization order, meaning any resultant combined spectrum will not violate the hierarchical relationship defined by the comparison of coherence spectra; specifically, the combined spectrum will always be ‘greater’ than or equal to its constituent spectra in terms of majorization. This allows for systematic exploration of achievable coherence states and demonstrates that more complex states can be generated while respecting the fundamental constraints imposed by the majorization ordering principle.

The computational efficiency of determining the supremum and infimum points within the coherence spectra analysis scales inversely with the square of the number of polygon vertices (N) used in the representation. Specifically, the convergence rate is O(N^{-2}). This indicates that doubling the vertex count (N) reduces the computational error by a factor of four, demonstrating a quadratic improvement in precision. While higher vertex counts yield more accurate results, the computational cost increases proportionally to the square of the count, necessitating a trade-off between accuracy and processing time when selecting an appropriate vertex density for analysis.

The Fragility of Boundaries: Smoothness, Singularities, and System Resilience

A robust system, characterized by a ‘SmoothBoundary’, exhibits a remarkable tolerance to fluctuations in its internal coherence. This means that even when the precise conditions driving the system’s response undergo slight variations, the resulting output remains largely stable and predictable. Such boundaries suggest an inherent resilience, where minor disruptions to the coherence spectrum don’t trigger disproportionately large changes in achievable responses. This stability is critical in many complex systems, from neural networks processing noisy signals to engineered materials maintaining structural integrity under stress; a smooth boundary implies the system can effectively ‘absorb’ small errors or uncertainties without catastrophic failure, ensuring consistent and reliable performance across a range of operating conditions.

A system defined by a ‘SingularBoundaryPoint’ exhibits a precarious balance, where even the slightest alterations in input coherence can trigger disproportionately large shifts in its output. This extreme sensitivity implies a lack of robustness; the system doesn’t gracefully handle minor disturbances but instead reacts dramatically. Such boundaries represent critical thresholds where predictability diminishes, and the system’s behavior becomes highly contingent on precise conditions. Understanding these singular points is crucial, as they highlight vulnerabilities and potential failure modes within the system, demanding careful calibration and control to avoid unintended consequences arising from seemingly insignificant variations.

The categorization of system boundaries as either smooth or singular offers a powerful lens for understanding its inherent stability and capacity for predictable responses. A smooth boundary indicates a robust system, tolerant to minor fluctuations in input coherence – meaning small changes won’t drastically alter the achievable outcomes. Conversely, a singular boundary reveals a delicate balance, where even minimal coherence variations can trigger substantial shifts in system behavior. This distinction isn’t merely descriptive; it’s fundamentally linked to the system’s reliability and its ability to maintain consistent performance under real-world conditions. Identifying these boundary characteristics, therefore, provides critical insights for designing more resilient and predictable systems, allowing for a nuanced understanding of how a system will respond to perturbations and uncertainties.

The sensitivity of a system’s boundaries can be further understood by examining the entropy of its coherence spectrum. Entropy, in this context, quantifies the degree of disorder or randomness within the distribution of coherence values; a higher entropy suggests a broader, more unpredictable range of achievable responses for a given input. Consequently, boundaries exhibiting high entropy demonstrate greater susceptibility to even minor variations in coherence, amplifying the impact of disorder and potentially leading to instability. Conversely, low-entropy boundaries indicate a more ordered coherence spectrum, suggesting a robustness to coherence fluctuations and a more predictable system behavior. By integrating entropy as a metric, researchers gain a nuanced understanding of how disorder within the coherence landscape directly influences a system’s sensitivity at its operational limits, revealing crucial insights into its overall stability and resilience.

A defining characteristic of these coherence boundaries lies in their inherent geometry. Mathematical proofs establish that at both the supremum – the point of maximum achievable response – and the infimum – the point of minimal response – the dimensionality of the normal cone is consistently n-1, where n represents the dimensionality of the system’s parameter space. This isn’t merely a numerical coincidence; it reveals a fundamental geometric constraint governing the system’s behavior at its limits. Essentially, the system exhibits a specific number of ‘degrees of freedom’ along which it can vary without crossing the boundary, a number directly linked to the overall dimensionality of the problem. This consistent dimensionality suggests a robust, underlying structure to these boundaries, offering a powerful tool for characterizing and predicting system stability and response changes as coherence parameters are altered.

The pursuit of optimal bounds, as demonstrated within this study of wave coherence, echoes a fundamental principle of all systems: their inherent limitations. Just as the supremum and infimum define the achievable range of wave behavior, so too does every system exist within a defined temporal and physical space. Erwin Schrödinger observed, “The total number of states of a system is not something that can be determined beforehand.” This resonates with the finding that merely identifying minimum and maximum coherence isn’t enough; the entire set of coherence, its boundaries defined by these extremes, dictates the potential. Technical debt, in a sense, is the accumulation of states outside these optimal bounds, a divergence from the system’s inherent potential gracefully aged.

The Inevitable Erosion of Optimality

The demonstration that optimal bounds for wave coherence reside not in extremal values, but in the supremum and infimum of the coherence set, feels less like a resolution and more like a refined articulation of the problem. Any improvement in bounding, any approach to ideal observability, ages faster than expected. The field will undoubtedly pursue increasingly complex coherence spectra, chasing ever-tighter bounds-yet the inherent limitations of any physical system guarantee that these gains will be transient. The pursuit of optimality is a journey towards diminishing returns, a predictable decay of advantage.

Future work will likely focus on the implications of this majorization-based theory for specific wave phenomena-imaging, signal processing, perhaps even quantum optics. However, the underlying principle remains: the arrow of time dictates that any precisely defined optimum will, through unavoidable perturbations, become merely a point of reference within a broader, less-defined range.

Rollback – the attempt to reconstruct past states or refine initial conditions – is a journey back along the arrow of time, and as such, is fundamentally constrained. The true challenge lies not in achieving ever-finer bounds, but in understanding the nature of that decay, and building systems that age gracefully within its inevitability.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10665.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Gold Rate Forecast

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Yakuza Kiwami 3 And Dark Ties Guide – How To Farm Training Points

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Meet the cast of Mighty Nein: Every Critical Role character explained

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

- How to Build a Waterfall in Enshrouded

- These Are the 10 Best Stephen King Movies of All Time

2026-01-19 01:39