Author: Denis Avetisyan

This review explores how non-Hermitian physics unlocks new control over resonant behavior in Fabry-Pérot systems, enabling the creation of exceptional points and subwavelength manipulation of light.

The article details the influence of parity-time symmetry, radiation boundary conditions, and propagation matrix formalism on exceptional points and resonant frequencies in non-Hermitian resonators.

Conventional understandings of optical resonance are challenged by systems exhibiting non-Hermitian behavior, leading to phenomena beyond those predicted by standard theory. This work, ‘Non-Hermitian Fabry-Pérot Resonances’, characterizes these resonances in high-contrast resonator systems, focusing on the roles of exceptional points and the skin effect induced by engineered gauge potentials. Our analysis, utilizing a propagation matrix formalism, demonstrates that exceptional points can arise solely from radiation conditions and that the non-Hermitian skin effect uniformly influences resonant modes, leading to broadband edge localisation. Could these findings pave the way for novel designs of robust and tunable optical devices with enhanced functionalities?

Beyond Conventional Resonance: Embracing Asymmetry

Conventional resonator analysis fundamentally depends on the application of Hermitian conditions – mathematical constraints ensuring that a system’s energy remains conserved and wave propagation is reciprocal, meaning signals travel equally well in both directions. However, this reliance inadvertently restricts the investigation and implementation of non-reciprocal phenomena, where wave behavior differs depending on the direction of travel. Such limitations pose a significant hurdle in the development of advanced optical and acoustic devices that necessitate asymmetric wave propagation – for instance, isolators that allow signals to flow in one direction only, or sensors with dramatically enhanced sensitivity. By adhering to Hermitian constraints, researchers have historically overlooked a vast parameter space where breaking reciprocity unlocks functionalities unattainable in traditional resonator designs, paving the way for entirely new classes of devices.

The constraints of traditional resonator analysis significantly impede the development of devices demanding precise control over wave direction and exceptionally fine detection capabilities. Many emerging technologies-including advanced sensors, unidirectional waveguides for optical computing, and highly selective filters-rely on the ability to propagate waves asymmetrically, a feat difficult to achieve within the confines of Hermitian systems. Furthermore, enhancing a device’s sensitivity often necessitates resonators with sharply defined resonances; however, conventional designs struggle to deliver the necessary quality factors and fine-tuning options for optimal performance. This limitation particularly affects fields like biomedical diagnostics and environmental monitoring, where detecting minute changes in physical or chemical properties is crucial, driving the need for innovative approaches that circumvent these fundamental restrictions.

The exploration of non-Hermitian systems presents a compelling route beyond the limitations inherent in traditional resonator analysis. Unlike their Hermitian counterparts, these systems-characterized by non-reciprocal interactions and asymmetric energy flow-offer the potential to engineer devices with functionalities previously unattainable. This departure from conventional physics allows for the manipulation of resonance behavior, enabling enhanced sensitivity in sensors, novel optical isolators, and advanced signal processing capabilities. Researchers are discovering that by deliberately introducing gain and loss, or by exploiting parity-time (PT) symmetry, it becomes possible to control wave propagation in unprecedented ways, leading to the creation of devices where signal directionality and amplification are finely tuned and optimized. The ability to circumvent the restrictions of reciprocity opens doors to a new generation of photonic and acoustic technologies with significant implications across multiple scientific and engineering disciplines.

Characterizing resonances in non-Hermitian systems presents a significant analytical hurdle due to the potential for exceptional points where resonant frequencies coalesce. Unlike traditional Hermitian systems where resonances merge linearly, non-Hermitian physics allows for coalescence orders scaling with \delta^{3/2}, where δ represents a perturbation parameter. This cubic scaling dramatically complicates the identification and control of resonances, as even minute changes in system parameters can lead to rapid and substantial shifts in resonant behavior. Understanding this higher-order coalescence is crucial not only for accurately predicting system responses but also for engineering devices that leverage these unique properties – such as highly sensitive sensors or novel optical switches – where precise resonance tuning is paramount. The complexity demands advanced theoretical frameworks and experimental techniques capable of resolving these subtle, yet impactful, changes in resonant spectra.

A Compact Model: The Generalized Capacitance Matrix

Characterizing resonant behavior when feature sizes are significantly smaller than the wavelength of excitation – the subwavelength regime – presents computational challenges for traditional electromagnetic modeling techniques. Direct simulation of these structures often requires extremely fine discretization, leading to high memory demands and processing times. Consequently, a compact and efficient method for representing system behavior is essential; this necessitates reducing the dimensionality of the problem while still accurately capturing the dominant physical effects. Methods that achieve this, such as the Generalized Capacitance Matrix, allow for the extraction of key parameters – like resonant frequencies and quality factors – with reduced computational cost compared to full-wave simulations, enabling practical analysis and optimization of subwavelength resonators.

The Generalized Capacitance Matrix (GCM) is a systems-level approach to modeling resonant structures operating in the subwavelength regime, offering a computationally efficient alternative to full-wave electromagnetic simulations. It represents the resonator as an interconnected network of capacitive elements, allowing for the characterization of resonance behavior through eigenvalue analysis. The matrix elements are derived from geometrical and material property information, effectively encapsulating the physical characteristics of the resonator within a compact mathematical form. This formulation allows for the prediction of resonant frequencies and field distributions without requiring explicit solution of Maxwell’s equations, making it particularly suitable for analyzing complex, multi-dimensional resonators and optimizing their performance parameters.

The Generalized Capacitance Matrix (GCM) determines resonance frequencies by directly relating a resonator’s physical characteristics to its electromagnetic behavior. Accurate input of geometric dimensions-including length, width, and height of constituent parts-and material properties, specifically permittivity and permeability tensors, allows the GCM to model the charge distribution within the resonator. Solving the eigenvalue equation derived from the GCM- \text{det}(Z - \lambda I) = 0 where Z is the impedance matrix, λ represents the eigenvalue, and I is the identity matrix-yields a set of resonant frequencies corresponding to each eigenvalue. The precision of these calculated frequencies is directly proportional to the accuracy of the initial geometric and material property inputs, providing a quantifiable link between design parameters and observed resonance.

The Generalized Capacitance Matrix method’s effectiveness is significantly enhanced when paired with the correct boundary conditions, as these conditions directly influence the resulting characteristic determinant. The determinant, when set to zero, yields an equation whose solutions are the eigenvalues of the system. These eigenvalues are not merely abstract values; they fundamentally dictate the order of the zero-crossing in the characteristic determinant, and consequently, define the resonant frequencies of the subwavelength resonator. Accurate determination of these eigenvalues is therefore critical for precise modeling and prediction of resonator behavior, particularly when analyzing complex geometries or material properties.

Unveiling the Singularities: Exceptional Points and Beyond

Non-Hermiticity, a departure from the requirement of Hermitian operators in quantum mechanics, arises when material properties are described by complex values or when a system experiences asymmetric boundary conditions. Traditionally, Hermitian operators guarantee real eigenvalues, corresponding to stable energy levels. However, introducing non-Hermiticity allows for complex eigenvalues, indicating gain or loss in the system. This, in turn, leads to the emergence of Exceptional Points (EPs) in the parameter space of the Hamiltonian. EPs are points where two or more eigenvalues and their corresponding eigenvectors coalesce, signifying a singularity in the system’s eigenvalue spectrum and a breakdown of the conventional eigenvalue analysis. The presence of EPs dramatically alters the system’s response, leading to phenomena such as enhanced sensitivity to perturbations and unidirectional wave propagation.

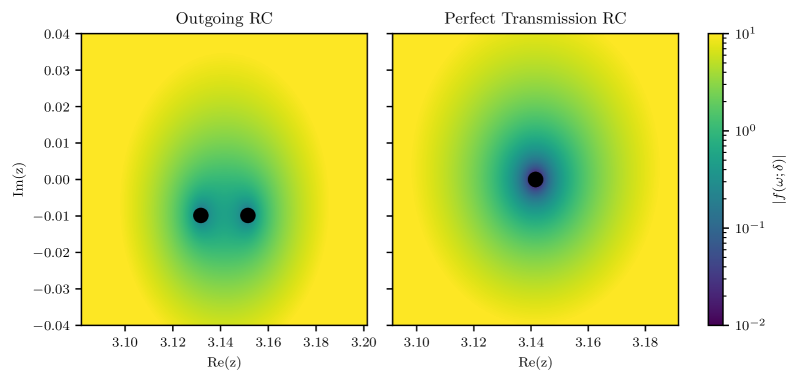

Exceptional Points (EPs) in non-Hermitian systems are characterized by the merging of two or more resonant frequencies, leading to a singularity in the parameter space. This coalescence fundamentally alters the behavior expected from traditional eigenvalue analysis, as the eigenvectors associated with these coinciding frequencies become linearly dependent. Consequently, the standard definition of eigenvalues – unique values defining the system’s resonant states – breaks down at EPs. At these points, a small perturbation in system parameters can induce dramatic changes in the eigenvalues and eigenvectors, a sensitivity not observed in Hermitian systems. This breakdown necessitates the use of alternative analytical tools, such as the Jordan normal form, to accurately describe the system’s behavior in the vicinity of an EP, and impacts the interpretation of observables like energy and decay rates.

The Perfect Transmission Condition (PTC) provides a mechanism for engineering non-Hermitian systems where Exceptional Points (EPs) can be reliably observed and manipulated. This condition, implemented as a specific boundary condition, forces complete transmission of waves at a designated interface, effectively creating an asymmetric coupling between system components. By precisely tailoring the PTC – specifically, by adjusting the coupling strength between the interacting regions – researchers can control the location and properties of EPs in the parameter space. This control is achieved by ensuring that the scattering matrix at the interface satisfies \hat{S} = \hat{S}^{\dagger} \hat{S} = \hat{I} , where \hat{S} is the scattering matrix and \hat{I} is the identity matrix. The PTC allows for the creation of systems where the Hamiltonian is non-Hermitian but possesses parity-time (PT) symmetry, a crucial requirement for the existence of EPs.

Leading-order non-Hermiticity offers a tractable approach to modeling systems exhibiting complex interactions near Exceptional Points by focusing on the lowest-order perturbation to a Hermitian Hamiltonian. This simplification allows for analytical treatment of resonant frequency convergence, demonstrating that the rate at which frequencies coalesce is proportional to the square root of the non-Hermitian perturbation, denoted as \delta^{1/2}. Specifically, the imaginary part of the eigenvalues, which dictates the decay rate of resonant states, scales with this \delta^{1/2} dependence, providing a quantitative measure of sensitivity to non-Hermitian effects and enabling predictions about system behavior near Exceptional Points without requiring full solutions to complex, higher-order equations.

The Edge of Localization: Unveiling the Non-Hermitian Skin Effect

The Non-Hermitian Skin Effect reveals a surprising tendency in certain physical systems: a dramatic accumulation of wave-like states, known as eigenmodes, at the boundaries of the material. Unlike traditional systems where energy is distributed relatively evenly, these non-Hermitian systems-those described by Hamiltonians that lack the symmetry of their Hermitian counterparts-exhibit a pronounced localization. This means that instead of spreading throughout the system, a substantial fraction of these modes are ‘pushed’ to the edges, effectively concentrating energy in specific locations. The effect isn’t merely a surface phenomenon; it fundamentally alters the system’s behavior, impacting how it responds to external stimuli and potentially leading to enhanced sensitivity or directional control. This localization is a direct consequence of the system’s non-Hermitian nature and is observable in a range of physical platforms, from photonic structures to electronic circuits, offering new avenues for device design.

The non-Hermitian skin effect arises from a fundamental connection to the system’s imaginary gauge potential, a concept borrowed from electromagnetism but applied here to the momentum space of the quantum system. This potential breaks the reciprocity inherent in traditional Hermitian systems, meaning that wave propagation is no longer symmetrical – a wave traveling in one direction experiences a markedly different response than one traveling in the opposite direction. Consequently, the system exhibits a directional sensitivity where modes preferentially accumulate at the boundaries, leading to the observed skin effect. This asymmetry isn’t a result of physical boundaries, but rather a property of the system’s effective Hamiltonian, sculpted by the complex, non-Hermitian terms which introduce this intriguing directional bias and drive the localization of N eigenstates to the system’s edges.

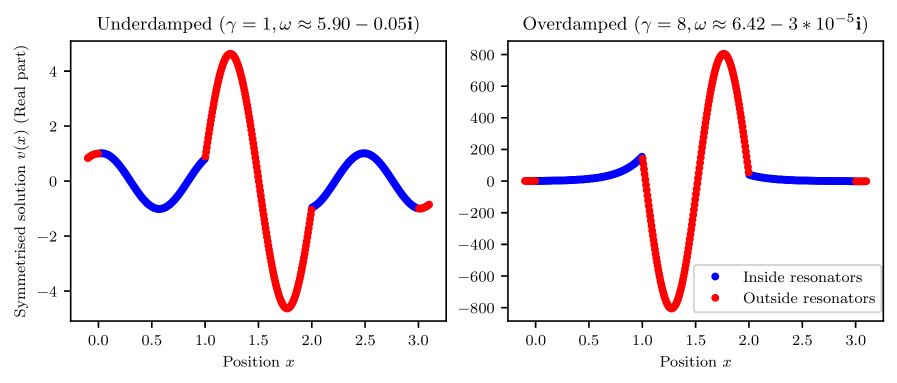

Floquet-Bloch theory emerges as a crucial analytical tool when investigating the non-Hermitian skin effect, extending traditional Bloch theory to encompass systems with spatially modulated, non-reciprocal potentials. While standard Bloch’s theorem relies on the translational symmetry of a system to define propagating modes, Floquet-Bloch theory accounts for the more general quasi-periodicity inherent in non-Hermitian systems exhibiting the skin effect. This involves transforming the problem into a Floquet space, effectively ‘unwinding’ the quasi-periodic potential to reveal a modified Bloch Hamiltonian. Analyzing the eigenvalues and eigenvectors within this Floquet space allows researchers to precisely characterize the localization properties and identify the generalized eigenvalues associated with the exponentially decaying or growing modes – described by e^{\gamma x} where γ denotes the complex-valued quasi-energy. The power of this framework lies in its ability to predict and understand the emergence of edge states and the associated non-trivial topological invariants, ultimately providing a pathway for designing systems with tailored wave localization characteristics.

The deliberate manipulation of the non-Hermitian skin effect holds significant promise for the development of advanced devices exhibiting both heightened sensitivity and precise directional control. This arises from the phenomenon’s ability to localize resonant modes – effectively concentrating energy – and govern their decay with a characteristic rate of e^{-Γ(x)}, where Γ(x) dictates the strength of localization at a given position. By engineering systems that exploit this controlled decay, researchers envision creating sensors capable of detecting minute changes in their environment, as well as waveguides that efficiently direct energy flow in a non-reciprocal manner. This precise control over mode localization opens avenues for innovations in areas such as optical and acoustic metamaterials, topological insulators, and potentially even quantum information processing, offering a pathway toward functionalities unattainable in traditional Hermitian systems.

Precision Tools: Wronskians and Outgoing Waves

The Wronskian, a determinant formed from the solutions of a differential equation, provides a powerful method for determining whether those solutions are linearly independent – a crucial characteristic for building a complete and unique solution space. Beyond simply verifying independence, the Wronskian also plays a significant role in identifying and characterizing resonance behavior within the system. Specifically, the Wronskian vanishing at certain points indicates the presence of resonances, where energy transfer is maximized and system response is dramatically altered. This mathematical tool isn’t merely an abstract concept; it directly informs the understanding of how waves propagate and interact, and is instrumental in analyzing the stability and behavior of complex systems described by differential equations, such as those encountered in quantum mechanics and wave optics – effectively functioning as a fingerprint of the system’s oscillatory characteristics. W(y_1, y_2) = \begin{vmatrix} y_1 & y_2 \\ y_1' & y_2' \end{vmatrix}

The Outgoing Radiation Condition establishes how wave behavior is constrained as it propagates towards infinity, a critical aspect of accurately modeling resonant systems. This condition dictates that waves should generally move away from the system being studied, preventing unphysical reflections from artificial boundaries in simulations or calculations. Without this stipulation, solutions can become unstable or fail to represent realistic physical phenomena; a resonance, for instance, could appear to gain energy indefinitely. Specifically, the condition requires that the wave function asymptotically take the form of an outgoing wave – one that diminishes in amplitude as it travels outwards. This ensures that any energy initially introduced into the system is ultimately radiated away, leading to stable and physically meaningful results when analyzing phenomena like energy transfer and decay rates in non-Hermitian systems. \lim_{r \to \in fty} \left( \frac{\partial F}{\partial r} + i k F \right) = 0 , where F is the wave function and k is the wave number, mathematically captures this outgoing behavior.

The reliable prediction of non-Hermitian device performance hinges on the development of robust numerical simulations, and these simulations are fundamentally built upon strong mathematical foundations. Techniques leveraging the Wronskian and outgoing radiation condition aren’t merely abstract tools; they provide the necessary constraints to ensure that computed solutions are both linearly independent and physically realistic, reflecting how waves behave at large distances. Without these mathematical safeguards, simulations can produce unstable or unphysical results, leading to inaccurate predictions of device characteristics like gain, loss, and resonant frequencies. Consequently, a precise application of these concepts is crucial for designing and optimizing non-Hermitian systems, enabling researchers to move beyond theoretical explorations and toward practical device implementation.

Investigations are poised to broaden the application of Wronskian analysis and outgoing wave conditions beyond currently studied systems, venturing into scenarios with increased dimensionality, disorder, and complex geometries. This expansion isn’t merely about computational challenge; it’s driven by the potential to unlock novel device functionalities stemming from non-Hermitian physics. Researchers anticipate designing systems exhibiting enhanced sensing capabilities, unidirectional transmission, and topologically protected edge states – features unattainable in traditional Hermitian frameworks. Further exploration could reveal entirely new classes of resonant phenomena and offer unprecedented control over wave propagation, potentially revolutionizing fields like metamaterials, photonics, and quantum information processing, with the mathematical tools serving as a crucial foundation for both theoretical understanding and practical implementation.

The exploration of non-Hermitian systems reveals a landscape where conventional notions of symmetry and resonance dissolve. This work, detailing the influence of modified radiation conditions on exceptional points, highlights how easily perceived stability can fracture under specific perturbations. It’s a reminder that rationality is a rare burst of clarity in an ocean of bias; the system doesn’t adhere to idealized mathematical constructs, but rather responds to the prevailing conditions, much like collective mood dictates market behavior. As Friedrich Nietzsche observed, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” and these resonators, pushed beyond conventional limits, demonstrate an unexpected robustness, revealing novel resonant behaviors beyond the subwavelength regime.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The pursuit of exceptional points in non-Hermitian systems feels, at this juncture, less like a search for novel physics and more like a sophisticated mapping of parameter space. The demonstrated control over resonant frequencies, while elegant, only underscores a familiar truth: systems respond predictably to manipulation. The real challenge isn’t finding these points, but understanding why anyone would care beyond the immediate demonstration of control. One suspects the utility will lie not in fundamental breakthroughs, but in the exploitation of sensitivity-a lever for finely tuned sensing, or perhaps a means of engineering instability.

The limitation, as always, resides in the assumptions baked into the models. Radiation conditions, parity-time symmetry – these are mathematical conveniences, not necessarily reflections of reality. To extend this work beyond the subwavelength regime requires a reckoning with the messy, imperfect world where boundaries aren’t sharply defined and dissipation isn’t perfectly controlled. The models function because they ignore the things that invariably break them.

Ultimately, this field will likely mirror the history of resonance studies generally: a slow drift from fundamental curiosity towards incremental technological improvement. It’s a predictable trajectory. Economics isn’t about markets; it’s about habit. And human beings, it seems, have a habit of finding the most mundane application for the most beautiful ideas.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.19855.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- How to Get to Heaven from Belfast soundtrack: All songs featured

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- 10 Most Memorable Batman Covers

- Star Wars: Galactic Racer May Be 2026’s Best Substitute for WipEout on PS5

- The USDH Showdown: Who Will Claim the Crown of Hyperliquid’s Native Stablecoin? 🎉💰

- Ashes of Creation Mage Guide for Beginners

- These Are the 10 Best Stephen King Movies of All Time

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Best X-Men Movies (September 2025)

2026-01-28 18:13