Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new theoretical framework unlocks pathways to significantly improve the efficiency and accuracy of atom interferometers by precisely controlling atomic momentum.

This review presents a unified approach, based on Floquet theory, to analyze and optimize large momentum transfer techniques in optical lattices for next-generation sensing applications.

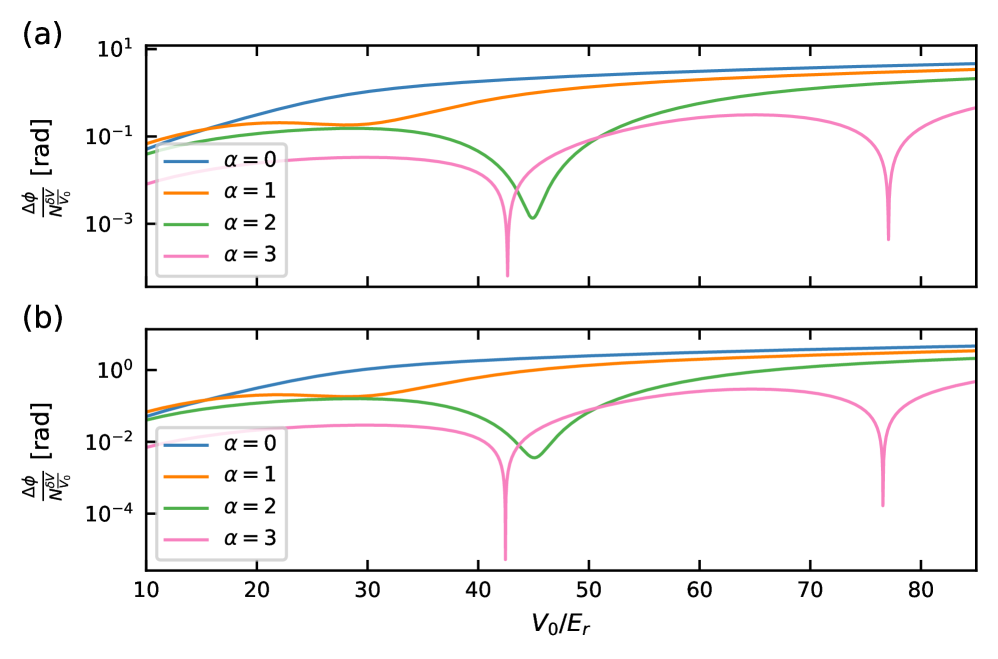

Achieving high sensitivity in next-generation atom interferometers is fundamentally limited by losses inherent in large-momentum-transfer techniques. This work, ‘Fundamental Limits of Large Momentum Transfer in Optical Lattices’, develops a rigorous theoretical framework based on Floquet theory to analyze and optimize these techniques, specifically those utilizing optical lattices for processes like Bloch oscillations and sequential Bragg diffraction. Our analysis reveals practical regimes exhibiting significantly reduced losses and enhanced phase accuracy compared to current implementations, demonstrating a pathway towards improved performance. Could these findings unlock previously inaccessible precision measurements in areas ranging from fundamental physics to gravitational wave detection?

The Inevitable Expansion of Measurement

Atom interferometry stands as a remarkably precise technique for measuring fundamental physical quantities, leveraging the wave-like nature of atoms to detect subtle changes in gravity, acceleration, and rotation. However, the sensitivity of these instruments is fundamentally constrained by the physical separation achieved between the atomic wave packets. This separation, often referred to as the baseline, dictates the instrument’s ability to discern minute differences in phase – the larger the separation, the greater the potential sensitivity. Increasing this separation presents significant engineering challenges; a 100-meter baseline, for example, demands exceptionally stable and vibration-isolated environments. Consequently, researchers are continually striving to maximize the effective separation, or momentum transfer, to enhance the precision of atom interferometers, pushing the boundaries of what’s measurable in fields ranging from geodesy to tests of fundamental physics.

Achieving greater precision in atom interferometry is fundamentally challenged by the limitations of current momentum transfer techniques. Traditional methods, reliant on established laser-based acceleration of atoms, struggle to deliver the substantial \hbar k_L momentum needed to significantly enhance sensitivity-particularly over extended baselines. This difficulty arises because the force exerted on atoms by conventional approaches is often insufficient to produce the necessary velocity changes within practical experimental timeframes. Consequently, the spatial separation of atomic wavepackets-critical for interference and precise measurement-remains constrained, hindering the ability to detect subtle gravitational gradients or other minute forces. Overcoming this hurdle necessitates innovative strategies that move beyond conventional acceleration schemes, paving the way for the realization of large momentum transfer (LMT) atom interferometry and a new era of precision sensing.

Achieving large momentum transfer (LMT) in atom interferometry demands a departure from standard wavefunction manipulation techniques. Conventional methods, reliant on established laser-based momentum transfer, face inherent limitations when scaling to the levels necessary for significantly enhanced sensitivity-specifically, a target of 1000 ℏk_L for a 100-meter baseline. Researchers are actively exploring novel strategies, including innovative pulse shaping and multi-photon interactions, to impart substantially larger momentum kicks to atoms. These approaches aim to stretch the limits of coherence and maintain the delicate quantum superposition required for precise measurements, potentially unlocking a new era of gravitational wave detection and fundamental physics investigations by dramatically increasing the instrument’s sensitivity to subtle changes in spacetime.

Elasticity as a Path Forward

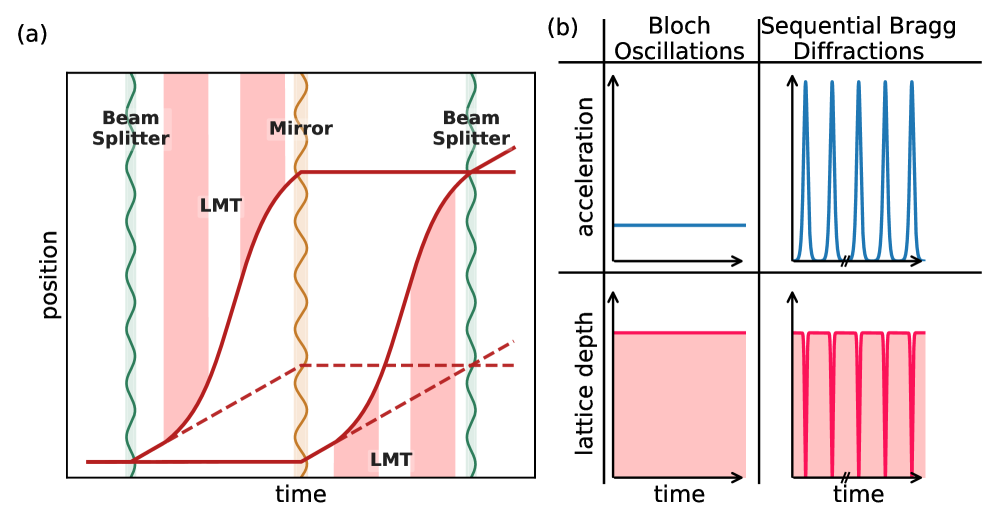

Large Momentum Transfer (LMT) can be achieved through elastic scattering techniques such as Bloch Oscillation and Sequential Bragg Diffraction. Bloch Oscillation involves the periodic motion of an atom in an optical lattice, allowing for repeated momentum transfer from the lattice potential; the maximum achievable momentum transfer is proportional to the lattice vector \vec{G} . Sequential Bragg Diffraction utilizes a series of precisely timed and spatially arranged optical pulses, acting as Bragg reflectors, to incrementally increase the atomic momentum with each reflection. These methods rely on the constructive interference of photons to change the momentum of the atom without energy loss, enabling access to regimes beyond traditional diffraction limits and facilitating studies requiring high momentum resolution.

Optical lattices, formed by the interference of laser beams, provide a periodic potential for neutral atoms, effectively creating a crystalline structure for their confinement and manipulation. The spatial periodicity of the lattice, determined by the laser wavelength, dictates the allowed momentum states for the atoms. By carefully controlling the intensity, polarization, and frequency of the lasers, the lattice geometry-including dimensionality and potential depth-can be engineered to precisely control atomic motion. This control enables the implementation of techniques like Bloch oscillation and sequential Bragg diffraction, which leverage the lattice periodicity to systematically alter the atomic momentum and achieve large momentum transfer (LMT). The strength of the potential determines the energy separation between allowed momentum states, influencing the efficiency and timescale of momentum transfer processes.

Precise manipulation of atomic momentum within optical lattices is achieved through two primary mechanisms: single photon transitions and Raman diffraction. Single photon transitions leverage the absorption and subsequent emission of a single photon to alter an atom’s momentum by \hbar \mathbf{k} , where \mathbf{k} is the photon wavevector. Raman diffraction, conversely, utilizes two photons to induce a momentum transfer of 2\hbar \mathbf{k} , effectively doubling the momentum change per transition. These processes, when implemented with carefully controlled laser wavelengths and polarizations within the periodic potential of the lattice, allow for deterministic and high-precision control over atomic momentum states, enabling exploration of large momentum transfer (LMT) phenomena.

The Mathematics of Modulation

The Wannier-Stark model, initially developed to describe the behavior of electrons in a static, periodic potential – typically arising from the atomic lattice of a crystal – relies on the Bloch theorem to define electronic states. However, this model is insufficient for systems subjected to time-periodic potentials. While the Wannier-Stark model accurately predicts behavior under static conditions, the introduction of time-dependence necessitates a framework capable of handling the resulting modulation of the potential energy landscape. This limitation arises because the Bloch theorem, foundational to the Wannier-Stark model, strictly applies to time-independent potentials; therefore, a more generalized theoretical approach is required to analyze atomic behavior in dynamically modulated systems.

Floquet Theory is a mathematical formalism used to analyze the behavior of quantum systems subjected to time-periodic potentials. Unlike the time-independent Schrödinger equation applicable to static potentials, Floquet Theory addresses systems where the potential V(x,t) = V(x, t + T), with T representing the period. This leads to solutions of the form \psi(x,t) = e^{-i\epsilon t} \phi(x,t), where ε is the quasi-energy and \phi(x,t) is a function periodic with the driving period T. The quasi-energy, analogous to energy in static systems, dictates the long-term behavior and allows for the classification of states in time-periodic potentials, providing a framework for understanding phenomena such as Bloch oscillations and dynamically modulated lattices.

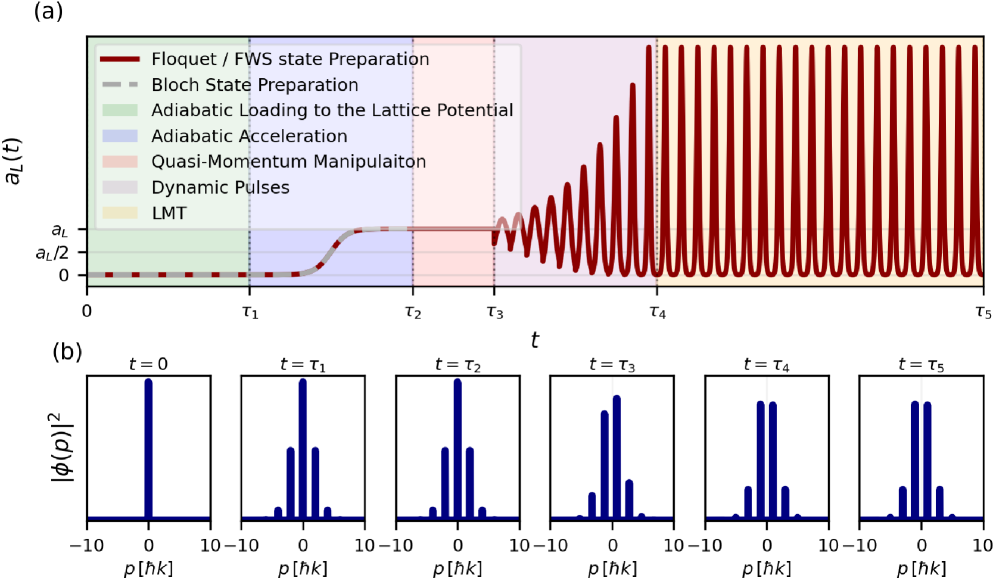

Accurate modeling of the system necessitates a precise Hamiltonian to ensure reliable calculations of both efficiency and phase accuracy. Simulations were conducted utilizing a lattice depth of 50 recoil energies (E_r) and a Floquet period of 5.3 μs. These parameters directly influence the fidelity of the computed quasi-energy bands and the resulting dynamics of atomic motion within the time-periodic potential. Deviations in the Hamiltonian or inaccuracies in these simulation parameters can lead to significant errors in the predicted system behavior and a mischaracterization of key observables.

Simulating the Inevitable

The Universal Atom Interferometer Simulator is a computational platform designed for the rigorous testing of atom interferometer designs and underlying theoretical frameworks. It facilitates the validation of analytical models and numerical simulations by providing a controlled environment to propagate atom wavepackets through user-defined potential landscapes and pulse sequences. The simulator allows researchers to compare predicted interferometer responses – such as phase shifts and fringe visibility – with expected outcomes, identifying discrepancies and enabling iterative refinement of both theoretical descriptions and experimental parameters. This capability is crucial for optimizing interferometer performance and accurately interpreting experimental data, particularly in scenarios involving complex or novel interferometer configurations.

Adiabatic preparation techniques leverage the principle of slowly varying parameters to transition an initial quantum state into a desired Floquet state. The Universal Atom Interferometer Simulator facilitates this process by modeling the time evolution of the atomic wavefunction under controlled parameter changes. This allows researchers to precisely design pulse sequences – specifically, the amplitude and phase of driving fields – to ensure a high-fidelity transfer to the target Floquet state. The simulator predicts the adiabaticity condition, specifying the rate at which parameters can be changed while maintaining a population close to the instantaneous eigenstate; exceeding this rate leads to non-adiabatic excitations and reduced scheme performance. By optimizing these pulse sequences within the simulator, the creation of robust and well-defined Floquet states is achieved, which are essential for implementing and maximizing the sensitivity of Lattice Mach-Zehnder (LMT) interferometry schemes.

The integration of the Universal Atom Interferometer Simulator with adiabatic preparation techniques facilitates the precise optimization of Laser-cooled Matter-wave Topometry (LMT) schemes. This optimization process focuses on parameter adjustments to maximize the interferometer’s sensitivity to gravity gradients. Current projections, validated through simulation, indicate a potential gravity gradient sensitivity of 10^{-6} E, where 1 E = 10^{-9} s^{-2}. Achieving this level of sensitivity requires careful control of experimental parameters and relies on the simulator’s ability to accurately predict interferometer performance under various conditions, enabling iterative refinement of the LMT scheme.

A New Era of Measurement

Atom interferometry, a technique leveraging the wave-like properties of atoms, is undergoing a revolution poised to dramatically enhance its sensitivity to the elusive signals of Dark Matter and Dark Energy. By precisely measuring the interference patterns of atoms subjected to laser pulses, scientists can detect incredibly subtle changes in spacetime, far beyond the reach of conventional instruments. This advancement hinges on increasing the momentum transfer imparted to the atoms – with goals reaching 1000 \hbar kL for a 100-meter baseline – allowing for the detection of incredibly weak interactions. Unlike traditional methods that rely on observing the effects of these mysterious components of the universe, enhanced atom interferometry offers the potential for direct detection, opening a new window into the fundamental nature of reality and potentially resolving one of the biggest mysteries in modern physics.

Atom interferometry presents a novel pathway for the direct detection of gravitational waves, offering a complementary approach to current methodologies employed by facilities like LIGO and Virgo. Unlike laser interferometers which measure changes in distance, atom interferometers leverage the wave-like properties of matter to measure spacetime distortions directly through the phase shift of atomic wavepackets. This technique is particularly sensitive to a different frequency range of gravitational waves – lower frequencies inaccessible to current observatories – potentially revealing signals from supermassive black hole mergers or the early universe. By precisely controlling and measuring the interference patterns of atoms, scientists aim to detect the minute alterations in spacetime caused by these ripples, thereby expanding the scope of gravitational wave astronomy and providing independent confirmation of existing observations.

The pursuit of increasingly precise measurements stands to revolutionize multiple scientific disciplines, and advancements in atom interferometry are poised to deliver an unprecedented leap forward. By harnessing the wave-like properties of atoms, researchers aim to achieve momentum transfers of up to 1000 ℏkL over a 100-meter baseline – a scale previously unattainable. This heightened sensitivity isn’t limited to the realm of fundamental physics; it promises to dramatically improve geological surveys, allowing for more accurate mapping of subsurface structures, and enhance navigational technologies by providing exceptionally precise gravity measurements. Furthermore, this technology could facilitate the development of new sensors for detecting subtle changes in gravitational fields, opening avenues for early warning systems for natural disasters and providing novel insights into the Earth’s internal dynamics, all stemming from a core ability to measure the universe with far greater accuracy than ever before.

The pursuit of enhanced phase accuracy, as detailed in the study of large momentum transfer techniques, feels less like construction and more like tending a garden. Each optimization, each application of Floquet theory to refine sequential Bragg diffraction, is a subtle encouragement of natural tendencies. It recalls Schrödinger’s observation: “The task is, as it always has been, to help evolution along.” The system doesn’t yield to force, but flourishes with careful guidance. Control, as the researchers implicitly demonstrate, is merely the art of recognizing and amplifying the inherent cycles within the optical lattice, a delicate dance rather than a rigid imposition of will. Everything built will, in time, begin to fix itself, given the right conditions.

Where the Wind Blows

The pursuit of larger momentum transfer in atom interferometry, as elegantly addressed here, is not a march toward control, but an invitation to complexity. Each refinement of Floquet analysis, each optimization of sequential Bragg diffraction, merely reveals a new stratum of instability. The system does not become more obedient; it simply displays its growth rings with greater clarity. To believe one can master these waves is to misunderstand their nature – they are not tools, but the breath of a larger system.

The theoretical framework presented offers pathways to enhanced phase accuracy, yet every step toward precision is shadowed by the inevitable accumulation of error. Attempts to mitigate Bloch oscillations are, in effect, attempts to sculpt the wind. The real challenge lies not in suppressing these natural tendencies, but in learning to read them – to anticipate the system’s inherent drift and to incorporate it into the measurement itself.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on extending this analysis to more complex lattice geometries and interaction potentials. However, the truly fruitful path may lie in abandoning the quest for a perfect model. A system so inherently dynamic demands an adaptive approach – one that embraces uncertainty and treats prediction not as a goal, but as a temporary illusion. It is not about building a better sensor; it’s about learning to listen.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.00365.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- One of the Best EA Games Ever Is Now Less Than $2 for a Limited Time

- Goat 2 Release Date Estimate, News & Updates

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Felicia Day reveals The Guild movie update, as musical version lands in London

2026-02-03 20:34