Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new perturbative approach challenges traditional geometric optics models of gravitational lensing, revealing subtle effects previously overlooked in calculations.

![The study establishes a coordinate system centered on the lens, utilizing spherical coordinates <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> (\theta, \phi, r) </span> to define the lens metric <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> [Eqs. (87) and (109)] </span>, and further refines this approach by transitioning to a flat spacetime coordinate system centered on the source for initial condition placement, effectively modeling geodesic deviation based on the closest radial distance to the impact parameter <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> b </span>.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.10239v1/refBHS1.jpeg)

This review details a method using the BE expansion and Newman-Penrose formalism to compute corrections to gravitational lensing beyond the eikonal approximation, demonstrating no leading-order phase shift proportional to GM/ω and highlighting the significance of tracking first-order BE corrections.

While geometric optics provides a foundational understanding of gravitational lensing, it fails to capture wave-like effects crucial at certain wavelengths. This motivates the study presented in ‘Gravitational lensing beyond the eikonal approximation’, which develops a perturbative framework to compute corrections beyond the standard eikonal approximation using the Newman-Penrose formalism. Our analysis reveals that leading-order phase shifts proportional to $GM/\omega$ are absent in vacuum, with wave effects initiating at order $G^2$, and demonstrates the importance of tracking first-order corrections to accurately model lensing phenomena. Could a more complete understanding of these wave-optic effects refine our interpretation of gravitational signals and provide new insights into strong-field gravity?

The Inevitable Diffraction: Beyond Ray Optics

The foundational principles of geometric optics, which treat light as rays traveling in straight lines, offer a remarkably effective and computationally efficient means of modeling wave propagation in many scenarios. However, this simplification inherently breaks down when the wavelengths of light become comparable to, or smaller than, the dimensions of the objects or features it encounters. In such instances, the wave nature of light – manifesting as diffraction and interference – becomes dominant, and the ray approximation loses accuracy. This failure isn’t merely a matter of precision; it fundamentally alters the predicted behavior of light, leading to discrepancies between theoretical predictions and experimental observations. Consequently, accurate modeling in these regimes necessitates the incorporation of wave corrections that account for these diffractive effects, moving beyond the limitations of the simple ray model and embracing the full complexity of wave optics.

While ray optics provides a valuable first approximation of how light propagates, a complete understanding of wave behavior necessitates acknowledging diffraction effects. When light encounters an object or aperture comparable in size to its wavelength, the simple straight-line paths predicted by ray tracing break down; instead, light bends and spreads, interfering with itself to create complex patterns. This phenomenon, known as diffraction, fundamentally alters the wavefront and requires corrections to the ray approximation to accurately model the resulting field distribution. Failing to account for diffraction leads to significant errors in applications ranging from microscopy and lithography to astronomical imaging, where resolving fine details relies on precisely capturing the nuances of wave propagation. Consequently, advanced modeling techniques must incorporate these wave corrections to achieve a faithful representation of light’s behavior and unlock the full potential of optical systems.

Calculating the wave corrections necessary when light interacts with structures comparable to its wavelength often relies on the diffraction integral – a fundamentally complex mathematical operation. While theoretically accurate, directly evaluating this integral demands significant computational resources, particularly for intricate or large-scale systems. The integral requires summing contributions from every point on an aperture or diffracting object, a process that scales rapidly with the number of points and the required precision. This computational burden can render traditional approaches impractical for real-time applications or detailed simulations, motivating the development of more efficient approximation techniques and algorithms. Consequently, researchers continually explore methods to reduce the computational cost without sacrificing essential accuracy in modeling wave phenomena.

Perturbing the Straight Line: The BE Expansion as a Corrective

The BE expansion provides a perturbative method for determining corrections to the predictions of geometric optics, specifically concentrating on first-order amplitude corrections to the propagating wave. This approach systematically calculates deviations from the geometric optics approximation by expanding the wave field as a series, allowing for quantitative assessment of phenomena not captured by ray tracing. Unlike direct numerical integration of wave equations, the BE expansion offers a computationally efficient alternative for analyzing wave propagation, enabling the determination of amplitude corrections with reduced computational cost. The resulting series provides a means to estimate the error introduced by geometric optics and refine the model for improved accuracy in wave-based calculations.

The BE expansion employs a series expansion to approximate the total wave field as a sum of terms, each representing a higher-order correction to the base geometric optics solution. This approach contrasts with traditional methods that rely on evaluating complex integrals to determine wave propagation, which can be computationally expensive, particularly for large or intricate systems. By expressing the wave field as a series – typically involving parameters like frequency ω and lens characteristics – the BE expansion allows for efficient calculation of wave amplitude corrections, reducing computational demands while maintaining accuracy to a specified order. The efficiency stems from replacing integration with algebraic manipulation of the series terms, offering a significant advantage in scenarios requiring numerous calculations or real-time processing.

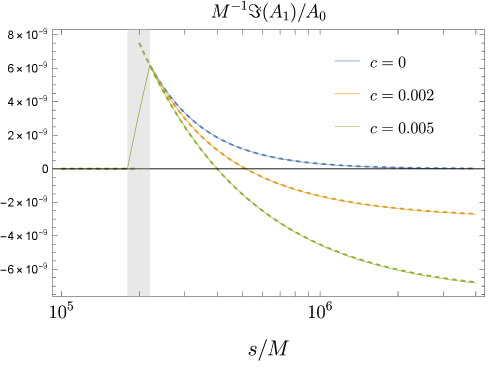

The predictive capability of the BE expansion is fundamentally linked to accurate quantification of the induced phase shift in the propagating wave. Analysis demonstrates the absence of a leading-order phase shift term proportional to GM/ω, where G represents the gradient index, M is a characteristic length scale, and ω is the angular frequency. This finding is significant as it deviates from expectations based on simpler models and indicates that the initial phase change is not dominated by this particular parameter combination. Precise determination of this phase shift, and the confirmation of this absent term, is therefore critical for validating and applying the BE expansion in scenarios requiring accurate wave propagation modeling.

The BE expansion accounts for frequency-dependent phase modulation, providing a more accurate representation of wave propagation through a thin lens. Analysis demonstrates a phase shift proportional to Σ/ω, where Σ represents the lens sum parameter and ω is the angular frequency. This phase shift diminishes with the square of the ratio between the transverse distance sL and the initial transverse distance s, specifically fading with (sL/s)^2. This frequency-dependent behavior and its spatial scaling are key refinements to traditional geometric optics approximations when modeling wave behavior post-transmission through a lens.

Spacetime as the Stage: Wave Propagation in a Curved Universe

Wave propagation within a gravitational field is fundamentally determined by the curvature of spacetime, mathematically represented by the Ricci tensor, R_{\mu\nu}. This tensor describes how the geometry of spacetime deviates from flatness and directly influences the paths that waves – including electromagnetic and gravitational waves – take through it. Specifically, the components of the Ricci tensor quantify the tidal forces experienced by particles or waves, causing them to converge or diverge. The geodesic equation, which defines the paths of free-falling objects and waves, incorporates the Ricci tensor to account for these deviations from straight-line trajectories in flat spacetime. Therefore, analyzing the Ricci tensor allows for precise modeling of how gravity bends and distorts wave fronts, leading to phenomena such as gravitational lensing and Shapiro delay.

The Weak-Field Approximation, a simplification of Einstein’s field equations, assumes that spacetime curvature is small, allowing for the linearization of the Einstein tensor. This approximation is valid in regions sufficiently far from massive objects, enabling the treatment of gravity as a perturbation on flat Minkowski spacetime. Consequently, gravitational lensing, the bending of light around massive objects, can be effectively modeled; the deflection angle is directly proportional to the mass of the lensing object and inversely proportional to the impact parameter. Calculations using this approximation demonstrate that light rays follow null geodesics, and the observed distortions of background sources – such as the formation of Einstein rings or arcs – provide observational constraints on the mass distribution of the lens, including dark matter content. The angular separation between multiple images of a lensed source is directly related to the Einstein radius, given by \theta_E = \sqrt{\frac{4GM}{c^2} \frac{D_L}{D_S}} , where G is the gravitational constant, M is the lens mass, c is the speed of light, D_L is the distance to the lens, and D_S is the distance to the source.

The Geodesic Deviation Subsystem is a mathematical framework used to determine the paths of objects – and therefore waves – within a curved spacetime. It focuses on solving for the trajectory of a reference geodesic – the shortest path between two points – and simultaneously calculating related spacetime quantities such as the Riemann curvature tensor and the Jacobi vector. The Jacobi vector, in particular, quantifies the separation between infinitesimally close geodesics, revealing how tidal forces distort spacetime and influence wave propagation. Solving the geodesic deviation equation, typically expressed as \frac{D^2 \xi^a}{d\tau^2} = -R^a_{bcd} v^b v^c \xi^d , where \xi^a is the separation vector, v^a is the tangent vector to the geodesic, and R^a_{bcd} represents the Riemann curvature tensor, provides the necessary information to model the bending of light and other electromagnetic waves as they travel through gravitational fields.

The Eikonal expansion is a technique used to approximate solutions to the wave equation in general relativity by separating the wave into amplitude and phase components. This is achieved by expressing the wave function as \Psi = A e^{i \phi} , where A represents the amplitude and φ the phase. The expansion utilizes the concept of areal distance r to describe spatial separation and the null wavevector k^\mu which satisfies k_\mu k^\mu = 0 , ensuring the wave propagates at the speed of light. By expanding the phase φ in terms of r and derivatives of φ, the wave equation can be reduced to a series of simpler equations, allowing for the approximate determination of wave propagation characteristics in curved spacetime. This method is particularly useful in analyzing gravitational wave propagation and gravitational lensing phenomena.

The Lens and the Star: Modeling Gravity’s Influence on Light

A crucial element in accurately modeling gravitational lensing effects hinges on a realistic depiction of the lensing mass itself, and the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) solution provides just that for stellar objects. This solution describes the internal structure of spherically symmetric stars, accounting for the effects of general relativity on their density and pressure profiles. Unlike simpler mass distributions, the TOV solution allows for a nuanced understanding of how mass is distributed within a star, considering factors like stellar radius and internal composition. Consequently, it enables more precise calculations of light deflection around these objects, moving beyond idealized point-mass approximations. By incorporating the TOV solution into lensing models, researchers can better constrain stellar parameters and gain deeper insights into the properties of both the lens and the background source, ultimately refining the overall understanding of the universe’s large-scale structure and the behavior of gravity itself.

Predicting how light bends around massive celestial bodies requires a robust framework that merges stellar structure with the principles of general relativity. Researchers achieve this by integrating the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) solution – a model detailing the internal structure of spherically symmetric stars – with the Weak-Field Approximation, which simplifies calculations when gravity isn’t overwhelmingly strong. This combination is then further refined using Ricci Lensing calculations, accounting for how the curvature of spacetime, as described by the Ricci tensor, affects light paths. The result is a predictive capability allowing scientists to model the deflection of light rays as they pass near these stellar objects, effectively using the star itself as a gravitational lens. This approach not only confirms theoretical predictions but also provides a means to infer properties of distant stars and galaxies by analyzing the distorted images they produce, offering insights into the universe’s composition and evolution.

Refining the analysis of gravitational lensing requires increasingly precise methodologies, and techniques such as the Thin Lens Approximation and careful consideration of gravitational time delays play a crucial role. The Thin Lens Approximation simplifies calculations by assuming the lensing object’s extent is small compared to the distances involved, allowing for efficient modeling of light deflection. However, a complete picture demands accounting for the fact that light travels at different rates through varying gravitational potentials-a phenomenon described by gravitational time delay. This delay, manifesting as a difference in arrival times for light rays taking different paths around the lens, provides valuable information about the lens’s mass distribution and the geometry of spacetime. By incorporating these effects, researchers can more accurately reconstruct the source’s image and extract detailed insights into the universe’s structure and evolution, moving beyond simplistic models to a nuanced understanding of lensing phenomena.

An alternative to the Born Expansion (BE) for calculating the deflection of light around massive objects lies in the Partial Wave Expansion. This technique decomposes the gravitational field into a series of waves, allowing for a distinct method of determining phase shifts experienced by photons. Notably, the Partial Wave Expansion reveals a persistent phase shift proportional to the ratio of the average convergence κ̄ to the characteristic angular frequency ω̄ even at distances well beyond the lensing object itself. This residual phase shift, independent of the BE’s assumptions, offers a complementary means of verifying lensing models and understanding the subtle distortions of spacetime, potentially revealing details about dark matter distributions and the overall geometry of the universe.

Calculations incorporating a small galaxy-characterized by a mass of 10^9 solar masses, a radius of 1 kiloparsec, a lens distance of 100 megaparsecs, and an observed wavelength of 10^{11} meters-reveal a first-order Born approximation correction to the light deflection with a magnitude of -4 x 10^{-6}. This value, though seemingly minuscule, demonstrates the sensitivity of gravitational lensing measurements to subtle effects within the lensing galaxy. It highlights the necessity of employing higher-order corrections-such as the Born expansion-for precise astrometric and time-delay analyses. The magnitude suggests that, while geometric optics provide a reasonable first approximation, accounting for these corrections improves the fidelity of models used to infer the mass distribution and cosmological parameters from observed lensing phenomena.

The accurate modeling of gravitational lensing relies fundamentally on the principles of geometric optics, but its applicability isn’t guaranteed for all scenarios. Investigations reveal that the standard condition for geometric optics – \kappā\omegā \gg 1 – is surprisingly conservative; the criterion \omegā \gg 1 alone is sufficient to ensure validity. This less restrictive condition arises from the relative contributions of different wave effects, and importantly, connects directly to the observation wavelength λ, the impact parameter b , and the lens size L . Specifically, when the wavelength is significantly smaller than b²/L , the wave nature of light becomes negligible, allowing for the simplified calculations inherent in geometric optics to provide an accurate description of light deflection around massive objects – a crucial consideration for interpreting lensing observations and refining stellar models.

The pursuit of accuracy in gravitational lensing, as detailed in this work, reveals a predictable truth about complex systems. The researchers’ move beyond the eikonal approximation-tracking first-order BE corrections-demonstrates that stability is often a deceptive indicator. As René Descartes observed, “It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well.” This paper doesn’t simply build a more precise model; it allows the system to reveal its inherent evolution. Long-held assumptions about phase shifts are overturned, not by force, but by attentive observation-a recognition that the true architecture of a system is discovered, not designed. The inevitable deviations from perfect geometric optics aren’t failures, but emergent properties of a dynamic reality.

What Lies Beyond the Horizon?

The absence of a leading-order phase shift proportional to GM/ω is not a null result, but a confession. It suggests the tidy assumptions of geometric optics – the very scaffolding upon which lensing calculations rest – are more brittle than anticipated. The system doesn’t merely deviate from these approximations; it whispers of a fundamentally different behavior awaiting discovery. Each perturbative correction isn’t a refinement, but a glimpse into the fractal complexity inherent in spacetime itself.

Future work will inevitably pursue higher-order terms in the BE expansion. But the true challenge lies not in computational power, but in conceptual shifts. Tracking the dynamics of these first-order corrections isn’t about improving accuracy; it’s about abandoning the illusion of static backgrounds. The lens isn’t a fixed entity, but a participant in the cosmic dance, its shape evolving with the very light it bends.

The silence of the system, however, is the most telling sign. A complete theory will not offer predictable errors, but an acceptance of inherent unpredictability. The lens doesn’t just distort; it remembers. And the faint echoes of these past interactions-the subtle phase shifts, the untracked deviations-are the true signal, if anyone is listening.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10239.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Uncovering Hidden Order: AI Spots Phase Transitions in Complex Systems

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Auto 9 Upgrade Guide RoboCop Unfinished Business Chips & Boards Guide

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- USD JPY PREDICTION

- These Are the 10 Best Stephen King Movies of All Time

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

2026-01-18 07:13