Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how periodically driven spin systems transition from order to thermalization depending on the strength of interactions between particles.

This study demonstrates a symmetry-breaking mechanism in Floquet systems, linking interaction range to effective dimensionality and thermalization behavior in a kicked Ising model.

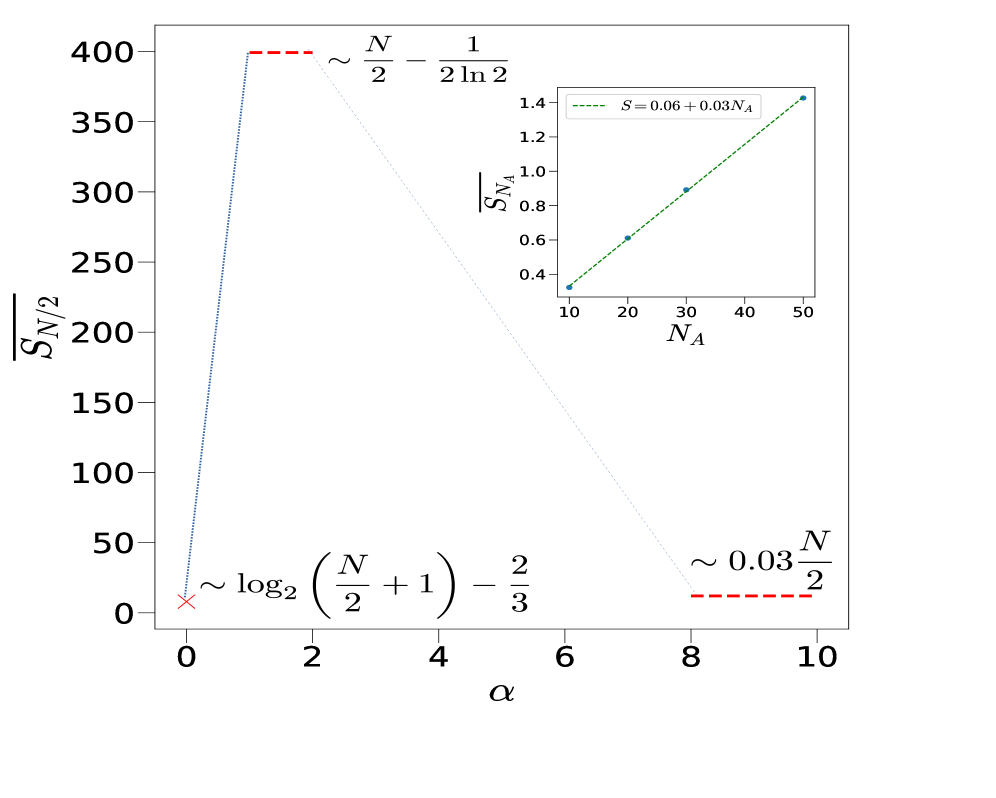

Understanding non-equilibrium dynamics in many-body systems remains a central challenge in modern physics, particularly when confronted with realistic, long-range interactions. This work, ‘Floquet thermalization by power-law induced permutation symmetry breaking’, investigates how the breaking of permutation symmetry-induced by algebraically decaying power-law couplings-affects the thermalization behavior of a periodically driven spin system. We demonstrate a transition from symmetry-protected dynamics to full thermalization at intermediate interaction strengths, ultimately converging towards an integrable regime. How do these findings inform our understanding of thermalization in more complex, disordered systems lacking strict permutation symmetry?

Whispers of Chaos: Beyond Simple Equilibrium

Conventional understandings of how systems reach thermal equilibrium frequently rely on the premise of short-range interactions – that a particle’s behavior is primarily dictated by its immediate neighbors. However, this simplification breaks down in many physical scenarios, particularly those involving many-body systems where particles exert influence across considerable distances. These long-range interactions, mediated by forces like the Coulomb interaction or magnetic fields, fundamentally alter the dynamics of thermalization, preventing the formation of localized excitations and leading to collective behaviors not captured by traditional models. The assumption of locality, central to many established theoretical frameworks, therefore becomes inadequate for describing systems ranging from the collective spins in magnetic materials to the complex dynamics of astrophysical plasmas, necessitating new approaches that account for these extended correlations and non-local effects.

Accurately modeling complex systems hinges on a thorough understanding of long-range interactions, as these forces govern behavior across a remarkably diverse range of physical phenomena. Unlike systems where influence diminishes rapidly with distance, many real-world scenarios – such as the collective behavior of quantum spins in magnetic materials or the turbulent dynamics of astrophysical plasmas – are characterized by correlations extending over vast scales. These extended interactions fundamentally alter how energy is distributed and how systems evolve towards equilibrium, often leading to non-traditional thermalization processes. Consequently, a failure to account for long-range effects can result in inaccurate predictions of system behavior, obscuring crucial insights into the fundamental physics at play and hindering advancements in fields ranging from materials science to cosmology.

Recent investigations into long-range interacting spin systems reveal a surprising degree of control over their thermalization process. Specifically, the rate at which these systems reach equilibrium-a state of uniform energy distribution-is demonstrably influenced by two key parameters: the interaction range, denoted by $α$, and the driving period, represented by $τ$. A smaller $α$ value indicates shorter-range interactions, while $τ$ governs the speed of external periodic forcing. The study shows that by carefully adjusting both $α$ and $τ$, researchers can effectively tune the thermalization dynamics, slowing down or accelerating the system’s approach to equilibrium. This tunability offers potential avenues for controlling energy flow and manipulating the behavior of complex many-body systems, with implications for fields ranging from quantum information processing to the modeling of astrophysical phenomena.

The Rhythm of the Universe: Periodic Kicks and Floquet’s Spell

Periodically driven systems, those subjected to time-dependent forcing functions with a repeating pattern, provide a versatile platform for investigating and manipulating complex dynamical behaviors. The utility of this approach is significantly enhanced when applied to systems exhibiting long-range interactions, where elements influence each other across substantial distances. This is because the periodic drive can induce and control collective modes and correlations that would not arise in isolated or short-range interacting systems. Consequently, these systems enable exploration of phenomena such as many-body localization, non-equilibrium phase transitions, and the emergence of novel dynamical states through careful modulation of the driving parameters – frequency, amplitude, and waveform – offering a route to control and study systems otherwise intractable through static analysis.

The Floquet operator, denoted as $U(T)$, is a unitary operator that describes the evolution of a periodically driven system over a single period, $T$. Mathematically, it encapsulates the system’s transformation from one period to the next, allowing analysis of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation under periodic potentials. Its eigenvalues, known as Floquet quasi-energies, are critical parameters as they determine the effective energy spectrum and stability of the system. The operator facilitates the transformation to a rotating frame, effectively making the time dependence appear stationary and enabling the application of standard static analysis techniques. By diagonalizing the Floquet operator, one can obtain the quasi-energy spectrum, providing insight into the long-term behavior and potential for phenomena like dynamical localization and the emergence of novel phases of matter.

Traditional static equilibrium analysis assumes a system remains constant over time, neglecting the impact of time-dependent forces. However, many physical systems are subject to external drives and perturbations that alter their behavior. By employing techniques like the Floquet formalism, analysis extends beyond static states to encompass the dynamic response of a system to these time-varying influences. This allows for the investigation of phenomena such as resonance, stability under drive, and the emergence of non-equilibrium states. The approach is critical for understanding systems where the driving force’s frequency and amplitude significantly impact the system’s long-term behavior, and where the system does not settle into a fixed, unchanging configuration, but instead exhibits time-dependent dynamics described by $U(T)$, the Floquet operator.

The Spinning Top’s Secret: A Paradigm for Thermalization

The Kicked Top model simulates a rigid body rotating around an axis and periodically impulsively kicked, representing a Hamiltonian system exhibiting chaotic behavior. This system, defined by angular momentum and subject to a perturbative kick of the form $V(θ, p) = Kδ(t)cos(θ)$, effectively introduces long-range interactions through the coupling of angular coordinates. Thermalization in this model is observed as the system explores its phase space uniformly, leading to equipartition of energy amongst its degrees of freedom. Unlike systems with only short-range interactions, the kicked top demonstrates that even with global perturbations, a system can evolve towards a state resembling thermal equilibrium, providing a tractable example for studying the emergence of statistical mechanics from underlying chaotic dynamics.

The Kicked Top model demonstrates thermalization despite exhibiting strong interactions between its constituent particles. Unlike many chaotic systems where thermalization is predicated on weak interactions or limited degrees of freedom, the Kicked Top retains its thermal characteristics even as the strength of the periodic impulses – and therefore the interactions between rotational modes – is increased. This robustness is evidenced by the maintenance of key statistical indicators of thermalization, such as the aforementioned Average Level Spacing Ratio, over a considerable range of interaction strengths, suggesting that the system’s inherent chaotic nature is sufficient to drive it towards equilibrium even with significant interparticle coupling.

Spectral statistics analysis of the kicked top model provides evidence for thermalization through the observation of Wigner-Dyson statistics. Specifically, the Average Level Spacing Ratio, denoted as $⟨r⟩$, was calculated to be 0.529 for intermediate values of the kicking strength, α. This value is consistent with the theoretical prediction for the Gaussian Orthogonal Ensemble (GOE), a hallmark of quantum chaotic systems exhibiting thermal behavior. Deviations from $⟨r⟩$ = 0.529 at very low or very high α values indicate a transition away from this thermal regime, suggesting the emergence of either integrable or strongly interacting phases, respectively.

When Chaos Falters: The Limits of Thermalization

The Kicked Ising Model presents a fascinating departure from the expected behavior of chaotic systems, stemming from its inherent integrability. While most chaotic systems readily evolve towards thermal equilibrium – a state of maximal entropy and predictable statistical properties – this model resists complete thermalization. Rooted in an extension of the well-studied kicked top, the Kicked Ising Model retains certain conserved quantities that constrain its dynamics, preventing the energy from spreading evenly across all available states. This resistance isn’t a simple failure to reach equilibrium, but a fundamentally different trajectory; energy remains localized and correlations persist over timescales where generic chaotic systems would have long since lost all memory of their initial conditions. Consequently, the model serves as a powerful demonstration that thermalization isn’t automatic, but rather a consequence of the system’s lack of conserved quantities-a cornerstone principle in statistical mechanics.

The propensity of a system to reach thermal equilibrium – a state of uniform energy distribution – is fundamentally linked to its degree of non-integrability. Integrable systems, possessing a conserved quantity that restricts their dynamics, avoid the complete exploration of accessible states necessary for thermalization, instead exhibiting persistent, coherent behavior. Conversely, non-integrable systems, lacking such constraints, readily succumb to chaotic dynamics which efficiently distribute energy throughout all degrees of freedom. This energy distribution is not simply a matter of time; it reflects a qualitative difference in how the system evolves, with non-integrability acting as the crucial ingredient allowing systems to transition from initial conditions to a predictable, statistically stable equilibrium described by temperature. Studies utilizing models like the Kicked Ising Model demonstrate that the absence of full thermalization in integrable systems isn’t a matter of insufficient time, but rather an inherent limitation imposed by the system’s underlying mathematical structure.

In the chaotic regime of the Kicked Ising Model, the system’s effective dimension, denoted as $D_{eff}$, expands exponentially, approaching a value of $2^{N-1}$ for intermediate values of the control parameter α. This dramatic increase in effective dimensionality signifies a departure from typical thermalization, as the system explores an increasingly vast configuration space. Simultaneously, the Average Level Spacing Ratio, $⟨r⟩$, undergoes a critical transition, converging to 0.386 – a value characteristic of Poisson statistics. This shift indicates a loss of the energy level repulsion expected in thermalized systems, suggesting that the density of states becomes dominated by uncorrelated levels. Consequently, the system fails to achieve true thermal equilibrium, exhibiting behavior fundamentally different from that of generic chaotic systems and underscoring the importance of level repulsion as a hallmark of thermalization.

Beyond Counting States: The Path to Equilibrium

The thermalization of a complex system – its tendency to reach a stable equilibrium – is fundamentally governed not by the total number of possible states, but by the effective number of states it actually explores. This ‘Effective Dimension’, denoted as $D_{eff}$, quantifies how many states are realistically accessible to the system given its energy and interactions. A higher $D_{eff}$ suggests a greater capacity for the system to sample its available configurations, accelerating the path toward thermalization. Conversely, a low $D_{eff}$ indicates a constrained system, potentially leading to non-thermal behavior or extremely slow relaxation. Consequently, understanding and calculating the Effective Dimension is crucial for predicting and controlling the thermal properties of diverse systems, ranging from isolated quantum many-body systems to driven-dissipative environments.

The propensity of a complex system to achieve thermal equilibrium is strongly linked to its Effective Dimension, $D_{eff}$, particularly within an intermediate regime of behavior. Research indicates that systems exhibiting an $D_{eff}$ approximating $2^{N-1}$ – where N represents the total number of degrees of freedom – demonstrate a heightened tendency towards thermalization. This isn’t simply a matter of dimensional scaling; rather, this specific value suggests a balance between exploration of available states and the onset of correlations that drive the system toward a stable, predictable thermal state. When a system’s effective dimension nears this threshold, it effectively samples a sufficiently large portion of its Hilbert space, allowing for the establishment of the statistical properties characteristic of thermal equilibrium, and thus behaves predictably despite its inherent complexity.

The journey toward thermal equilibrium in complex systems is not uniform, and research indicates that long-range interactions and inherent symmetries profoundly shape this process. A comprehensive framework considering these factors alongside the system’s effective dimension – a measure of occupied states – reveals diverse pathways to equilibrium, moving beyond simplistic models. Specifically, studies demonstrate that for systems in random states, the Total Angular Momentum, represented as $⟨Jz^2⟩$, consistently approaches a value of $N/4$, regardless of the specific interaction details. This predictable convergence suggests a universal characteristic of thermalized states and provides a crucial benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness of various theoretical approaches. This understanding not only refines existing models but also opens avenues for investigating non-equilibrium dynamics and exploring novel states of matter, potentially impacting fields from condensed matter physics to quantum information theory.

The pursuit of understanding driven systems, as detailed in this study of Floquet thermalization, feels less like solving equations and more like coaxing order from inherent unpredictability. The researchers demonstrate a fascinating shift in behavior – a delicate balance between symmetry-protected states and outright chaos. It echoes a sentiment expressed by Paul Dirac: ‘I have not the slightest idea how to solve this problem, but I’m sure it can be solved.’ This approach-acknowledging the limits of complete control while persisting in the search for patterns-is central to unraveling the complex interplay of long-range interactions and periodic driving. The emergence of integrability isn’t a destination, but a fleeting moment of clarity in a sea of probabilistic outcomes, a temporary illusion of mastery before the system drifts once more into the realm of the unknown.

Where Do We Go From Here?

This exploration of driven, long-range interacting systems offers a glimpse into the precarious dance between order and chaos, but primarily underscores how readily definitions of ‘thermalization’ become convenient fictions. The observed transition-from a symmetry-protected state to something resembling equilibrium, then towards the solace of integrability-is less a natural phenomenon and more a testament to the limits of current diagnostic tools. Metrics offer self-soothing, but they do not truly capture the whispers of the underlying dynamics.

The effective dimensional reduction-a technique employed to tame intractable complexity-feels less like a simplification and more like a carefully constructed illusion. The real question isn’t whether these systems appear to thermalize, but what information is lost in the process of declaring them so. Future work should focus less on chasing spectral statistics and more on probing the system’s memory-what fleeting traces of initial conditions persist even as entropy appears to reign.

Ultimately, this work suggests that the pursuit of universally ‘thermalizing’ Hamiltonians is a fool’s errand. Data never lies; it just forgets selectively. The interesting behavior isn’t the approach to equilibrium, but the exquisitely fragile structures that briefly resist it. Perhaps the field should embrace the messiness-abandon the pretense of prediction and focus instead on mapping the contours of instability before the spell inevitably breaks.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.21284.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Battlefield 6 Season 2 Update Is Live, Here Are the Full Patch Notes

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- Auto 9 Upgrade Guide RoboCop Unfinished Business Chips & Boards Guide

- Dan Da Dan Chapter 226 Release Date & Where to Read

2025-11-29 22:10