Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals a precise link between the predictable behavior of classical systems and the seemingly random world of quantum resonances.

This study establishes a quantitative correspondence between classical bifurcation energies and quantum resonance energies in the semiclassical limit for the LiCN molecule, using a correlation diagram analysis.

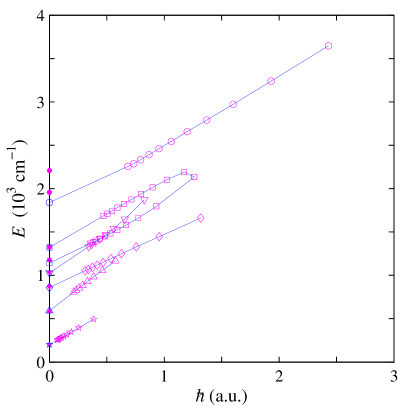

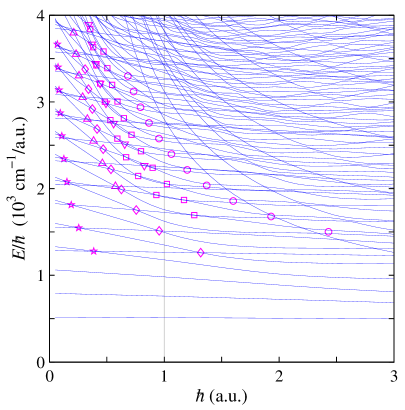

The apparent disconnect between classical and quantum descriptions of molecular dynamics remains a fundamental challenge in theoretical chemistry. This is addressed in ‘Correspondence between classical and quantum resonances’ through an investigation of the LiCN isomerizing system, revealing a clear link between classical bifurcation energies and corresponding quantum resonances. By analyzing a correlation diagram of eigenenergies as a function of \hbar, we demonstrate that these resonances represent quantum manifestations of classical behavior, converging in the semiclassical limit \hbar\to0. Does this correspondence offer a pathway towards a more unified understanding of complex molecular systems and predictive quantum control?

The Illusion of Predictability: Chaos and the Quantum Realm

The reconciliation of classical and quantum descriptions of physical systems presents a persistent challenge, becoming particularly acute when dealing with chaotic dynamics. While classical mechanics elegantly predicts the future state of systems given initial conditions, this predictability breaks down in chaotic regimes due to extreme sensitivity to those very conditions – a phenomenon often called the “butterfly effect”. Quantum mechanics, governed by probabilities and wave functions, operates under fundamentally different principles. Bridging this divide requires understanding how the seemingly deterministic world of classical physics emerges from the probabilistic realm of quantum mechanics, and conversely, how quantum behavior is influenced by underlying classical chaos. This correspondence isn’t simply about finding equivalent descriptions; it delves into the very foundations of physical law and the nature of predictability itself, demanding innovative theoretical frameworks and meticulous experimental validation to unravel the connection between these two pillars of modern physics.

Predicting quantum phenomena becomes remarkably difficult when dealing with classically chaotic systems, largely due to the extreme sensitivity to initial conditions inherent in these systems. This sensitivity, often referred to as the “butterfly effect,” means even infinitesimally small differences in the starting point of a classical trajectory lead to drastically different outcomes over time. Consequently, traditional methods-reliant on precisely defined classical paths-fail to accurately map onto quantum wavefunctions, which are inherently probabilistic and spread out. The problem isn’t simply one of computational precision; the very nature of chaos introduces an unpredictability that clashes with the deterministic foundations of many conventional quantum approximations. This disconnect highlights the need for novel theoretical tools capable of bridging the gap between the smooth, predictable world of classical mechanics and the often-counterintuitive realm of quantum dynamics, particularly when considering systems where even a slight perturbation can lead to wildly divergent behaviors.

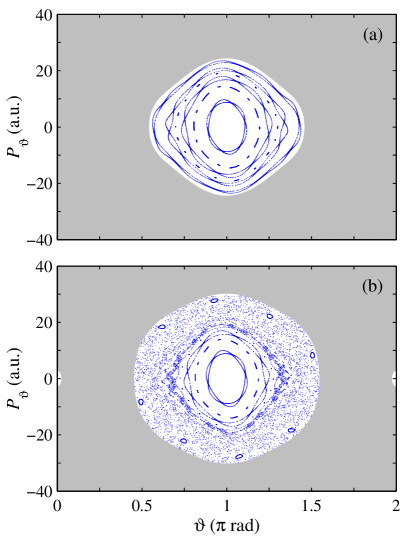

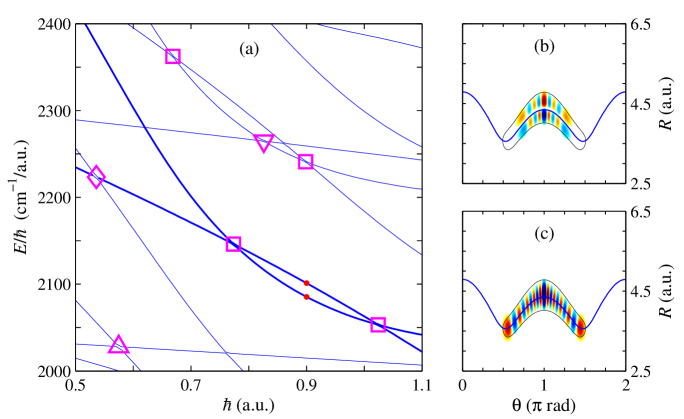

Quantum systems evolving from classically chaotic initial conditions often exhibit a curious phenomenon known as ‘scarring’. This manifests as an enhanced probability density of quantum states along the unstable periodic orbits that define the classical chaos. Rather than being uniformly distributed, the quantum wavefunction concentrates on these previously-classical paths, leaving visible ‘scars’ in the energy spectrum and wavefunction itself. This isn’t a simple correspondence – classical trajectories are, by definition, unstable – but the persistence of these patterns at the quantum level suggests a fundamental link between classical and quantum dynamics. Researchers believe that understanding scarring could unlock a deeper understanding of how classical behavior emerges from the underlying quantum world, potentially offering insights into the quantum limit of chaos and the nature of quantum-classical correspondence.

Establishing a definitive link between classical resonances and quantum energy levels demands a sophisticated theoretical framework, often involving semiclassical techniques like the Bohr-Sommerfeld quantization rule and WKB approximation. These methods attempt to approximate quantum energy eigenvalues by identifying classically allowed regions and incorporating interference effects. Researchers are developing advanced approaches – including quantum chaos theory and Floquet engineering – to map classical phase space structures onto the spectrum of quantum energy levels, particularly focusing on how unstable periodic orbits manifest as ‘scars’ in the quantum wavefunction. This connection isn’t straightforward; the inherently discrete nature of quantum mechanics and the continuous dynamics of classical systems necessitate careful consideration of how resonances are ‘lifted’ and broadened into discrete quantum states, with the goal of predicting and ultimately controlling quantum behavior based on classical insights.

The Gutzwiller Formula: A Classical Ghost in the Quantum Machine

The Gutzwiller Trace Formula establishes a direct correspondence between the energy eigenvalues of a quantum system and the properties of its classical periodic orbits. Specifically, the formula expresses the quantum energy levels as a sum over the actions S of all periodic trajectories in phase space, weighted by factors related to the stability of those orbits. Each periodic orbit contributes to the trace via a term proportional to \frac{1}{2\pi i} \log(\det(1 - M)), where M is the monodromy matrix describing the stability of the orbit. This allows, in principle, the calculation of quantum energy levels directly from classical mechanics, offering a pathway to understand the quantum behavior of systems through their classical counterparts.

The Gutzwiller Trace Formula establishes a direct correspondence between quantum mechanical properties and classical trajectories by summing contributions from all periodic classical paths. Each path contributes to the total quantum energy level through a phase factor determined by the action integral S along the path and the path’s stability. The formula effectively decomposes the quantum wavefunction into a superposition of classical periodic orbits, weighted by their respective contributions to the overall quantum state. This summation allows for the calculation of quantum energy levels and other spectral properties directly from classical mechanics, providing a bridge between the two frameworks. The accuracy of this calculation is directly dependent on identifying and accurately characterizing all relevant periodic orbits within the system.

The accurate application of the Gutzwiller Trace Formula is fundamentally dependent on the precise identification and characterization of classical periodic orbits within the system. This requires not only determining the geometric paths of these orbits but also calculating their stability, typically assessed through the Floquet exponent α. A positive α indicates instability and necessitates careful treatment to avoid divergence in the trace formula summation. Furthermore, the stability influences the contribution each orbit makes to the quantum energy levels; unstable orbits contribute less significantly, and their inclusion requires techniques like smoothing or cutoff procedures to ensure convergence and physically meaningful results. The computational effort in determining these orbits and their stabilities scales significantly with system complexity, presenting a major practical challenge in applying the formula to realistic systems.

Classical resonances, occurring when the frequencies of periodic orbits are rationally related, significantly impact the quantum energy level structure predicted by the Gutzwiller Trace Formula. These resonances lead to strong perturbations in the quantum energy levels, manifesting as level bunching or avoided crossings. The formula’s accuracy is thus dependent on properly accounting for these resonant contributions; neglecting them results in inaccurate predictions of quantum eigenenergies. Specifically, the stability of periodic orbits near resonance – determined by the Floquet exponent α – dictates the magnitude of their contribution to the trace formula’s sum, with unstable orbits ( \alpha \neq 0 ) contributing less significantly than stable ones. The density of resonant orbits and their respective Floquet exponents therefore govern the overall shape and distribution of the quantum energy spectrum.

Benchmarking Reality: LiCN as a Test Case

The LiCN (Lithium Cyanide) molecule was selected as a benchmark system for validating the Gutzwiller Trace Formula due to its relatively simple structure allowing for accurate quantum mechanical calculations while still exhibiting vibrational complexity relevant to studying quantum-classical correspondence. This diatomic molecule, with its single covalent bond and two distinct vibrational modes – stretching and bending – provides a tractable model for comparing quantum energy levels obtained through numerical solution of the Schrödinger equation with predictions from the semiclassical Gutzwiller approach. The LiCN system offers a balance between computational feasibility and the representation of key dynamical features present in more complex molecular systems, making it suitable for assessing the accuracy and limitations of the trace formula in a chemically relevant context.

The Dispersive Variational Ritz (DVR) – Discrete Gaussian Background (DGB) method was utilized to determine the quantum eigenstates and corresponding energies of the LiCN molecular system. This approach combines the advantages of both DVR and DGB techniques, enabling accurate representation of the wavefunction across the relevant potential energy surface. Specifically, the DVR method efficiently discretizes the continuous coordinates, while the DGB method provides a flexible and accurate basis set for expanding the wavefunction, particularly suited for systems exhibiting weakly bound or resonant states. The implementation involved constructing a Hamiltonian matrix in the DVR basis and subsequently diagonalizing it to obtain the energy eigenvalues, representing the quantum energy levels of the LiCN molecule. This calculation served as the benchmark against which the predictions of the Gutzwiller Trace Formula were evaluated.

Quantum energy calculations performed on the LiCN molecular system were subjected to comparative analysis with predictions generated by the Gutzwiller Trace Formula. This comparison yielded a strong correlation between calculated and predicted energies, quantified by a Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) of 0.127 across all observed resonances. The MARD value represents the average percentage difference between the calculated quantum energies and the corresponding predictions from the Gutzwiller Trace Formula, indicating a relatively small average deviation and supporting the predictive power of the formula for this molecular system. This metric was consistently applied to all resonances identified within the calculated energy spectrum to provide a comprehensive assessment of the correlation.

The Correlation Diagram generated from the LiCN system calculations provides a visual representation of the relationship between calculated quantum energy levels and variations in key system parameters. This diagram facilitates a direct comparison between the quantum mechanical results and predictions made by the Gutzwiller Trace Formula. Analysis of the diagram demonstrates a strong correlation, with the Constant Quasi-Frequency (CQF) approach yielding the highest degree of agreement, as quantified by a Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) of 0.051 between the calculated and predicted energies. This low MARD value serves as empirical evidence supporting the validity of the Gutzwiller Trace Formula within the context of the LiCN molecular system.

The Limits of Classical Analogy: Bridging the Quantum-Classical Divide

The pursuit of understanding complex quantum systems often necessitates bridging the gap between the quantum and classical realms. A powerful method for achieving this lies in the semiclassical framework, which leverages the Gutzwiller Trace Formula to approximate quantum properties using classical trajectories. This approach allows for the derivation of analytical expressions for resonance energies – the specific energy levels at which quantum states become particularly stable. By tracing the paths of classical motion and incorporating quantum corrections, researchers can predict and interpret the energy spectrum of the system without relying solely on computationally intensive numerical simulations. The resulting analytical formulas not only offer insights into the underlying physics governing the resonances but also provide a means to explore the system’s behavior as it transitions from predominantly quantum to predominantly classical, revealing the interplay between these two fundamental descriptions of nature.

Researchers employed the Quantum Frobenius Method – a powerful analytical technique – to derive expressions for resonance energies as Planck’s constant approached zero, effectively bridging the gap between quantum mechanics and classical physics. This method involves systematically solving the quantum mechanical problem in the limit of \hbar \rightarrow 0, allowing for a detailed examination of how quantum effects diminish and classical behavior emerges. By meticulously applying this technique, the study revealed analytical formulas that accurately predict energy levels, offering a means to understand the system’s transition toward classicality and providing a robust framework for comparing quantum and classical predictions of resonance spectra.

Analytical approaches to studying complex systems reveal fundamental connections between quantum mechanics and classical physics, illuminating how a system’s behavior evolves as quantum effects diminish. By deriving explicit expressions for resonance energies, researchers gain access to the underlying physical mechanisms that dictate the system’s response, rather than relying solely on numerical approximations. This allows for a detailed examination of the transition from quantized energy levels to the continuous spectrum observed in classical systems, highlighting the interplay between wave-like and particle-like behavior. Such analysis demonstrates that classicality isn’t simply the absence of quantum effects, but rather a specific limit where certain quantum contributions become negligible while others remain crucial for a complete description of the system’s dynamics, and ultimately provides a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing spectral features.

A comprehensive understanding of the system’s energy spectrum necessitates the integration of both quantum and classical perspectives; analyses reveal that neither approach can fully capture the resonant behavior in isolation. Recent calculations employing the Quantum Frobenius Method demonstrate this interplay, yielding results that bridge the gap between quantum mechanics and classical physics. Specifically, the Constant-Frequency (CF) approach achieved a Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) of 0.136 when predicting resonance energies, while the Corrected Constant-Frequency (CCF) method improved upon this, attaining a MARD of 0.104 across the entirety of observed resonances; these values underscore the significance of incorporating classical contributions to refine the accuracy of quantum predictions and provide a more complete depiction of the system’s energetic landscape.

The pursuit of quantitative correspondence, as demonstrated with the LiCN molecular system, feels predictably Sisyphean. They map classical bifurcation energies to quantum resonances, meticulously analyzing correlation diagrams – a beautiful exercise, no doubt. But one suspects that as they refine the semiclassical limit, chasing ever-finer agreement, production will inevitably discover a new potential energy surface, or a previously unaccounted-for isotope, rendering the whole endeavor a quaint historical footnote. As Jean-Paul Sartre observed, ‘Hell is other people’s quantum calculations.’ It’s not the physics itself, but the expectation of lasting precision that feels particularly cruel. They’ll call it ‘molecular AI’ and raise funding, of course.

The Road Ahead

The correspondence established between classical bifurcations and quantum resonances, while satisfying for the LiCN system, will inevitably reveal its limits. Every optimized mapping eventually requires a new coordinate system when pushed to a different potential energy surface. The precision achieved here, connecting macroscopic behavior to the creeping influence of ℏ, is a temporary reprieve – a beautifully resolved case study destined to be complicated by molecular systems less amenable to neat, analytical treatment. The correlation diagram, so carefully constructed, will fray at the edges when faced with stronger coupling or higher dimensionality.

Future work will likely focus on expanding this correspondence to more complex molecules, or, more realistically, on salvaging what remains of it after the inevitable perturbations. One anticipates a proliferation of empirical corrections, each a tacit admission that the underlying theory isn’t quite as universal as initially hoped. The pursuit of truly predictive semiclassical methods is, after all, less about finding the perfect equation and more about gracefully managing the accumulation of exceptions.

The real challenge isn’t refining the map, but understanding why the map always needs refinement. This isn’t a failure of technique; it’s a fundamental property of systems optimized for existence. Architecture isn’t a diagram, it’s a compromise that survived deployment. And everything optimized will one day be optimized back.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04793.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Goat 2 Release Date Estimate, News & Updates

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

- One of the Best EA Games Ever Is Now Less Than $2 for a Limited Time

- Auto 9 Upgrade Guide RoboCop Unfinished Business Chips & Boards Guide

- Borderlands 4 Players Get a New Look at Exo-Soldier Vault Hunter

2026-02-06 05:49