Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study explores how future gravitational wave detectors could reveal subtle signatures of quantum gravity near black holes.

Researchers investigate the potential to constrain quantum gravity parameters using waveform analysis of extreme mass-ratio inspirals.

Despite the successes of Einstein’s General Relativity, a complete theory unifying gravity with quantum mechanics remains elusive. This motivates research into potential observational signatures of quantum gravity, as explored in ‘Imprints of quantum gravity effects on gravitational waves: a comparative study using extreme mass-ratio inspirals’. By analyzing gravitational waveforms from extreme mass-ratio inspirals around black holes, this study demonstrates that distinct loop quantum gravity black hole models yield differing levels of detectable quantum corrections. Could future space-based detectors, such as LISA, definitively constrain parameters governing the quantum nature of spacetime through these subtle gravitational wave signals?

The Breakdown of Reality: Singularities and the Limits of General Relativity

General Relativity, Einstein’s profoundly successful theory of gravity, arrives at perplexing predictions when describing the universe’s most extreme environments. The theory forecasts the existence of spacetime singularities – points where gravitational forces become infinite and the very fabric of spacetime breaks down – within black holes and at the universe’s initial moments during the Big Bang. These aren’t simply areas where GR requires finer resolution; rather, they represent genuine limitations of the theory itself. Where GR predicts infinity, physics as it is currently understood ceases to provide meaningful descriptions. This breakdown isn’t a flaw in observation, but an indication that GR, while incredibly accurate in most scenarios, is incomplete and requires a more fundamental theory to accurately portray conditions of immense density and energy.

The Singularity Theorem, a cornerstone of modern gravitational physics, rigorously establishes that the formation of singularities within General Relativity isn’t simply a consequence of mathematical idealizations, but an inherent property of gravity itself under certain conditions. Developed primarily by Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking, the theorem demonstrates that once a gravitational field becomes sufficiently concentrated – as occurs within black holes or at the universe’s beginning – the equations of General Relativity inevitably predict points where spacetime curvature becomes infinite and the laws of physics, as currently understood, cease to apply. This isn’t a flaw in the solution of the equations, but rather a limitation of the theory itself; the theorem proves that, given realistic assumptions about the behavior of matter and energy, singularities are unavoidable within the framework of General Relativity, signaling the necessity of a more complete theory – one likely involving quantum mechanics – to accurately describe these extreme environments.

The prediction of spacetime singularities by General Relativity isn’t simply a curiosity; it strongly indicates the theory’s incompleteness. At the extreme densities and energies found within black holes or at the universe’s very beginning, the smooth spacetime geometry described by Einstein’s field equations breaks down entirely. This failure isn’t a flaw in observation, but a fundamental limit to the theory’s applicability. Physicists posit that a successful description of these realms requires a quantum theory of gravity – a framework that reconciles General Relativity with the principles of quantum mechanics. Such a theory would effectively “smooth out” the singularities, replacing them with a more nuanced, quantum mechanical description of spacetime, potentially revealing that what appears as a point of infinite density is, in reality, a region governed by fundamentally different physical laws. The quest for this unifying theory remains one of the most significant challenges in modern physics.

A Granular Universe: Loop Quantum Gravity and the Fabric of Spacetime

Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) postulates that spacetime is not a smooth continuum as described by classical General Relativity, but possesses a granular structure at the Planck scale – approximately 1.6 \times 10^{-{35}} meters. This quantization arises from applying the principles of quantum mechanics to the geometry of spacetime itself. Instead of being infinitely divisible, spacetime is proposed to be composed of discrete, fundamental units represented by ‘spin networks’ and their evolution in time, ‘spin foams’. These networks are constructed from quantized areas and volumes, meaning area and volume are not continuous variables but take on discrete, quantized values. The fundamental loops, interwoven to form these networks, define the basic building blocks of space, leading to a discrete, loop-like structure at the Planck scale and suggesting a minimum possible length and area.

The quantization of spacetime in Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) necessitates the development of an Effective Metric to describe gravitational phenomena at macroscopic scales. Classical General Relativity predicts spacetime singularities – points where physical quantities become infinite – within black holes and at the Big Bang. LQG, by postulating a discrete structure to spacetime at the Planck scale, introduces a minimum length and area, preventing these infinities. The Effective Metric is constructed through a process of averaging over the discrete quantum states, effectively “smearing out” the singularity. This results in a modified Einstein field equation that lacks the singular solutions present in classical General Relativity, replacing them with regular, finite solutions and offering a potential resolution to the singularity problem. The resulting metric maintains agreement with General Relativity in the low-curvature limit, ensuring consistency with established observations.

Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) predicts deviations from the spacetime geometry described by classical General Relativity in the vicinity of black holes. These modifications arise from the quantization of spacetime and result in black hole solutions differing from the Schwarzschild or Kerr metrics. Specifically, LQG calculations have yielded two primary black hole types: BHI and BHII. BHI solutions exhibit quantum corrections that eliminate the central singularity, replacing it with a massive region, while BHII represents a non-singular, regular black hole solution throughout its interior. These solutions are characterized by modifications to the event horizon and alterations to the black hole’s mass and radius as determined by \rho = \frac{M}{4\pi r^3} , where ρ is the density, M is the mass, and r is the radius. The precise nature of these quantum corrections is dependent on the specific parameters used in the LQG calculations.

Whispers from the Abyss: Probing Quantum Gravity with Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals

Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) consist of a compact object – typically a stellar-mass black hole, neutron star, or white dwarf – orbiting and ultimately merging with a supermassive black hole (SMBH) millions or billions of times its mass. This extreme mass ratio creates a strong gravitational field near the SMBH event horizon, where quantum gravitational effects are predicted to be most prominent. The orbits are highly relativistic, and the gravitational waves emitted during the inspiral, merger, and ringdown phases carry information about the spacetime geometry in this strong-field regime. By precisely modeling these waveforms and comparing them with observational data from detectors like LISA, researchers aim to test the predictions of general relativity and search for deviations that could signal the presence of quantum gravity corrections to the classical black hole spacetime.

The AAKWaveform model is a numerical relativity-based approach designed for the efficient generation of gravitational waveforms emitted during the inspiral phase of Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs). It utilizes a frequency-domain integration scheme and a post-Newtonian approximation to model the dynamics and gravitational radiation. The FEWPackage is a software implementation of the AAKWaveform model optimized for speed and accuracy, enabling the rapid computation of waveforms across a wide range of EMRI parameters. This efficient implementation is crucial for conducting large-scale parameter estimation studies and searching for subtle effects predicted by quantum gravity theories, as it facilitates the generation of the necessary waveform templates for comparison with detector data. The model accurately captures the complex evolution of the inspiral, including effects such as precession and higher-order modes, allowing for a robust assessment of potential deviations from classical general relativity.

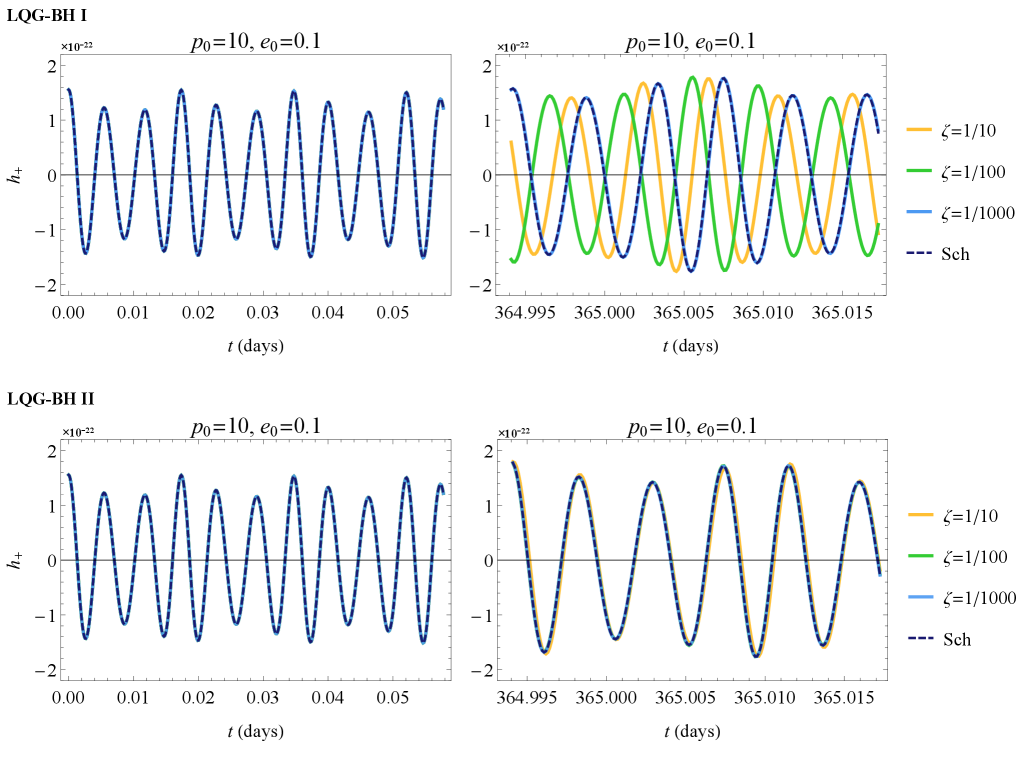

Comparison of gravitational waveforms generated from Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) black holes, designated BH-I and BH-II, with those predicted by classical General Relativity provides a means to search for evidence of quantum gravity effects. Deviations in waveform characteristics, resulting from the quantum nature of the black hole event horizon as described by LQG, could be detectable through analysis of signals from Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals. Current estimations suggest that detectable deviations, parameterized by the value of ζ, may be possible up to ζ \approx 10^{-3} for BH-I and ζ \approx 10^{-2} for BH-II, representing the sensitivity limits for distinguishing quantum and classical black hole signatures in observed gravitational wave data.

A New View of the Cosmos: LISA and the Future of Quantum Gravity Detection

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) represents a pivotal advancement in gravitational wave astronomy, poised to unveil a previously inaccessible universe of low-frequency signals. Unlike ground-based detectors, which are limited by seismic noise and terrestrial interference, LISA will operate in the quiet vacuum of space, utilizing three spacecraft millions of kilometers apart to form an enormous interferometer. This expansive configuration allows LISA to detect the subtle stretching and squeezing of spacetime caused by massive astrophysical events, specifically those emitting gravitational waves at frequencies too low to be observed from Earth. These include the mergers of supermassive black holes, extreme mass ratio inspirals (EMRIs), and potentially even signals hinting at new physics beyond the Standard Model, offering a unique window into the most energetic phenomena in the cosmos and a complementary perspective to existing gravitational wave observations.

The planned Laser Interferometer Space Antenna promises an unprecedented ability to discern the faintest ripples in spacetime, specifically through high-precision measurements of Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs). By achieving a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 30, LISA establishes a robust threshold for detectability, allowing scientists to identify subtle variations within EMRI waveforms that would otherwise be lost in noise. This enhanced sensitivity isn’t simply about detecting more events, but about extracting increasingly detailed information from each one; waveform discrepancies, even those representing incredibly small effects, can be reliably measured and analyzed. Such precision opens the door to testing fundamental physics, potentially revealing new insights into gravity and the nature of spacetime itself by pinpointing deviations from predictions made by classical general relativity.

LISA’s extraordinary precision extends beyond simply confirming predictions of general relativity; it offers a pathway to probing the elusive realm of quantum gravity. Researchers will employ a metric termed ‘Faithfulness’ to assess the detectability of subtle deviations from classical gravitational wave signals – deviations potentially caused by quantum corrections to spacetime geometry. These corrections are parameterized by a value, ζ, which represents the strength of quantum effects; LISA is anticipated to be sensitive enough to detect values of ζ greater than approximately 10⁻³ for black hole inspirals categorized as BH-I, and greater than 10⁻² for those classified as BH-II. This capability represents a significant leap, as it would provide the first observational constraints on quantum gravity, potentially unveiling the granular structure of spacetime at the Planck scale and fundamentally reshaping understanding of gravity itself.

The search for quantum gravity effects, as detailed in this study of extreme mass-ratio inspirals, reveals a fundamental truth about how humans approach complex problems. Even with perfect information – the precise waveform of a gravitational wave, for example – people choose what confirms their belief about the universe. This echoes Simone de Beauvoir’s observation that “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” because our understanding of reality isn’t simply received, but actively constructed through interpretation and confirmation. The researchers, like all model builders, operate within pre-existing frameworks, seeking evidence that aligns with, or subtly challenges, established theories. Most decisions, therefore, aim to avoid regret – the disconfirming of a cherished model – not maximize gain, even when dealing with the most fundamental forces of nature.

What Lies Ahead?

The search for quantum gravity, as this work illustrates, isn’t merely a hunt for equations that fit the universe. It’s an exercise in acknowledging the limits of control – a persistent belief that, with sufficient precision, one can predict the behavior of reality. Every chart produced from waveform analysis is, in a sense, a psychological portrait of its era – a testament to humanity’s enduring hope for mastery. The promise of LISA, and similar future detectors, lies not in finding quantum gravity – a singular answer feels increasingly unlikely – but in refining the boundaries of what remains unpredictable.

The inherent difficulty isn’t technical, but conceptual. The parameters these analyses attempt to constrain are, fundamentally, placeholders for ignorance. Each tightened bound on a quantum gravity parameter merely shifts the question: what other assumptions, baked into the models, remain untested? The true signal may not reside in the subtle distortions of gravitational waves, but in the persistent overestimation of predictive power.

Future investigations will undoubtedly refine the modeling of extreme mass ratio inspirals, pushing the boundaries of computational precision. Yet, a more fruitful path may lie in embracing the inherent uncertainty. Instead of seeking a single, elegant theory, the field might benefit from exploring the landscape of possible deviations from general relativity, treating each discrepancy not as a failed prediction, but as a clue to the complex interplay of factors beyond current comprehension.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.00185.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Epic Games Store Giving Away $45 Worth of PC Games for Free

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- These Are the 10 Best Stephen King Movies of All Time

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- 10 Great Netflix Dramas That Nobody Talks About

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- 10 Best Pokemon Movies, Ranked

2026-01-05 12:55