Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals a fundamental connection between a system’s momentum distribution and the extent of entanglement when translational symmetry is absent.

A non-zero expectation value for the translation operator directly implies long-range entanglement in one-dimensional systems lacking translational symmetry.

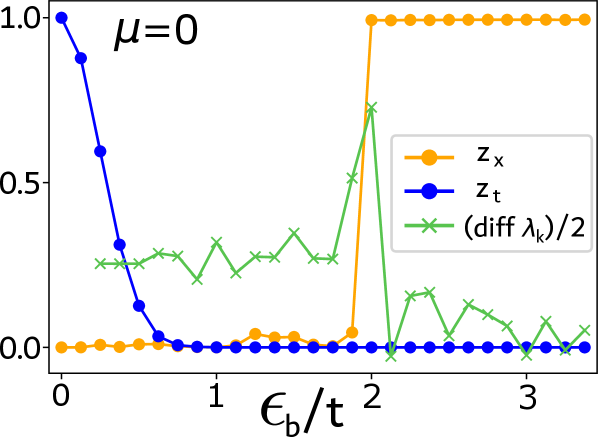

While established connections link momentum and long-range entanglement in translationally symmetric systems, characterizing entanglement in systems lacking this symmetry remains a significant challenge. Here, building upon the foundational work of Gioia and Wang, ‘Non-zero Momentum Implies Long-Range Entanglement When Translation Symmetry is Broken in 1D’, we demonstrate that the expectation value of the translation operator-<t>-acts as a robust proxy for localization and, consequently, long-range entanglement in one-dimensional systems with broken translational symmetry. Specifically, we find that a delocalized state necessarily exhibits |<t>| = 1 in the continuum limit. Does this momentum-space criterion offer a broadly applicable method for identifying and quantifying entanglement in more complex, disordered, or topologically ordered systems?

Unveiling Quantum States Through Momentum’s Whisper

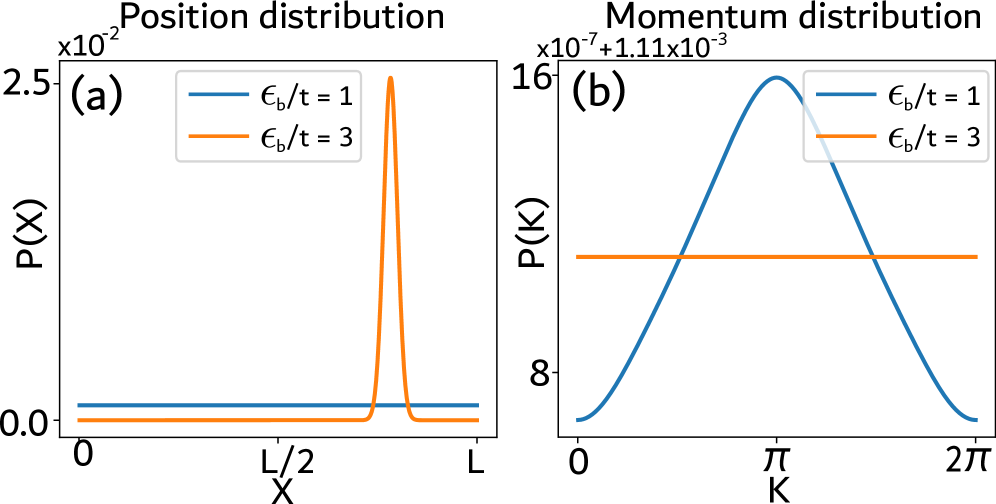

A quantum state is not simply defined by its energy, but crucially by how momentum is distributed within it – a distribution inherently governed by the Uncertainty Relation. This principle dictates an inverse relationship between the precision with which a particle’s position and momentum can be simultaneously known; a narrowly defined position necessarily implies a broad, uncertain momentum distribution, and vice-versa. Consequently, examining the momentum distribution – often visualized as a p-space representation – reveals fundamental properties of the state, such as its spatial extent and the likelihood of finding the particle with a specific momentum. States exhibiting sharp peaks in momentum space are highly localized in position, while broad momentum distributions signify a greater degree of positional uncertainty, demonstrating how the Uncertainty Relation fundamentally shapes the behavior and characteristics of all quantum states.

The momentum distribution of a quantum state offers a powerful lens through which to understand a particle’s spatial extent. Examining the spread of momentum values directly correlates to how localized or delocalized the particle is in space; a narrow momentum distribution indicates a highly localized particle, confined to a small region, while a broad distribution signifies a particle spread out over a larger area. This relationship isn’t merely descriptive, but is mathematically enshrined in the Uncertainty Principle – a fundamental constraint stating that the more precisely one knows a particle’s momentum, the less precisely one can know its position, and vice versa. Consequently, analyzing single particle eigenstates-the solutions to the Schrödinger equation for a single particle-reveals that states with well-defined momentum p are necessarily described by plane waves extending infinitely in space, representing complete delocalization, while states tightly confined in space exhibit a wider range of momentum components.

The principle of translation symmetry, a cornerstone of physics, profoundly dictates the allowable momentum states of a quantum system. This symmetry-the idea that physical laws remain unchanged by shifting the system’s location-directly implies a conservation of momentum and, crucially, shapes the possible momentum distributions a quantum state can exhibit. Because a system translating in space doesn’t experience a change in its fundamental properties, momentum becomes a ‘good’ quantum number, meaning definite momentum states are permissible solutions to the Schrödinger equation. Consequently, the momentum distribution isn’t arbitrary; it’s constrained by the symmetry, favoring states with well-defined momentum values and restricting highly localized or rapidly oscillating wavefunctions that would violate this fundamental principle. This link between symmetry and momentum isn’t merely a mathematical convenience; it’s a deep connection revealing that the very structure of space influences the possible states of matter.

Quantifying Confinement: The Localization Length Revealed

The Localization Length, denoted as ξ, quantitatively describes the spatial confinement of a quantum state. It is defined as the standard deviation of the particle’s position, calculated from the wavefunction \psi(x) using the formula \xi = \sqrt{\langle x^2 \rangle - \langle x \rangle^2}. A smaller Localization Length indicates a more tightly confined state, with a higher probability of finding the particle within a narrow spatial region. Conversely, a larger value signifies a more spread-out or delocalized state, where the particle’s position is less certain. This metric provides a precise and objective measure of spatial extent, allowing for comparisons between different quantum states and systems.

The Localization Length is inversely proportional to the width of the momentum distribution, a consequence of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the Fourier transform relationship between position and momentum space wavefunctions. Quantitatively, a smaller Localization Length – approaching zero – signifies a highly confined quantum state with a correspondingly broad momentum distribution, indicating a large uncertainty in momentum. Conversely, an infinite Localization Length indicates a completely delocalized state, where the wavefunction extends infinitely in space, and the momentum is precisely defined – or, more accurately, the momentum distribution approaches a delta function at a specific value. This relationship is fundamental in understanding the spatial extent and momentum characteristics of quantum states and is mathematically expressed through the properties of the Fourier transform.

Establishing the validity of the Localization Length as a quantifiable metric in macroscopic systems requires consideration of both the Continuum Limit and the Thermodynamic Limit. The Continuum Limit addresses the approximation of discrete energy levels with a continuous spectrum, which is crucial for systems with many particles; deviations from this limit can introduce inaccuracies in localization calculations. Simultaneously, the Thermodynamic Limit, where the number of particles approaches infinity while maintaining constant density, ensures that finite-size effects do not dominate the observed localization behavior. Applying these limits allows for the extraction of universal properties of localization, independent of specific boundary conditions or system size, and provides a framework for comparing localization characteristics across different materials and dimensions.

Mapping Quantum Behavior: Operators and Resta’s Insight

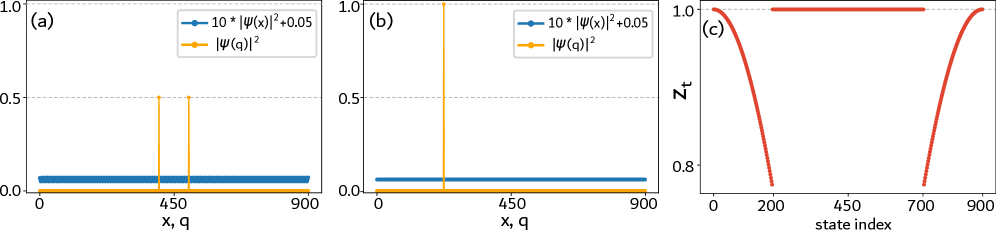

The translation operator, denoted as T(a), acts on a quantum state |\psi\rangle by shifting its spatial coordinate by a constant value a, resulting in a new state |\psi(a)\rangle = T(a)|\psi\rangle. This operator is fundamentally linked to the momentum operator via the Fourier transform; specifically, the expectation value of the translation operator, \langle T(a) \rangle, directly relates to the Fourier transform of the wavefunction and thus provides information about the momentum distribution of the quantum state. Analyzing \langle T(a) \rangle as a function of a allows for the characterization of the state’s momentum properties, including its average momentum and the spread or uncertainty in momentum. Its mathematical formulation enables precise calculations of these momentum-related quantities, offering a powerful tool for analyzing quantum systems.

The Momentum Distribution, a fundamental characteristic of a quantum state, can be directly assessed through the Expectation Value of the Translation Operator \hat{T}(p). This operator, when applied to a wave function, effectively shifts the probability distribution in momentum space. A higher Expectation Value, approaching 1, indicates a broader, more dispersed distribution, and thus a greater degree of delocalization in momentum space. Conversely, lower values suggest a more localized momentum distribution. This connection provides a quantitative link between the operator’s properties and the physical interpretation of momentum spread within the quantum system, enabling the characterization of states based on their momentum behavior.

Resta’s Formula establishes a quantifiable relationship between a quantum state’s Localization Length and the Modular Position Operator. This formula demonstrates a correlation wherein the magnitude of the Expectation Value of the Translation Operator – \langle T \rangle – is inversely proportional to the Localization Length. Specifically, larger values of \langle T \rangle indicate a greater degree of delocalization and, consequently, a longer Localization Length. This allows for the calculation of the Localization Length based on measurable operator expectation values, providing a direct method for characterizing the spatial extent of a quantum state.

A Controlled System: The Deterministic Dimer as a Testbed

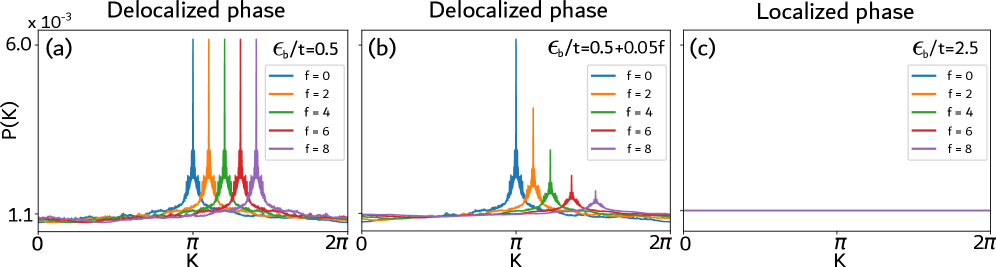

The Deterministic Dimer model, a simplified yet robust system in condensed matter physics, provides a uniquely controlled environment for investigating the fundamental relationship between a particle’s localization and its momentum distribution. Unlike systems with inherent randomness, the dimer’s predictable structure allows researchers to precisely define particle positions and then analyze how confinement impacts momentum characteristics. This precise control is invaluable; by systematically varying the dimer’s parameters – such as the spacing between potential wells – scientists can observe how the probability of finding a particle with a specific momentum changes as the particle transitions between fully localized and increasingly delocalized states. The model, therefore, serves not merely as a computational convenience, but as a crucial tool for validating theoretical predictions concerning the interplay between spatial confinement and the uncertainty principle, offering intuitive insights into more complex quantum systems where such relationships are often obscured by disorder and many-body interactions.

The momentum distribution, representing the probability of finding a particle with a specific momentum, serves as a crucial diagnostic tool when investigating the deterministic dimer model. By meticulously analyzing this distribution, researchers can directly validate the accuracy of theoretical predictions concerning the model’s behavior, and confirm whether the mathematical formalism aligns with the observed quantum phenomena. This comparison isn’t merely a verification exercise; the resulting insights provide an intuitive grasp of how localization and momentum are intertwined within the system. Specifically, deviations from expected distributions reveal the degree to which the dimer’s structure constrains particle movement, while agreement solidifies the understanding of its quantum properties and allows for increasingly complex model extensions to be explored with confidence.

Investigations into the effects of flux insertion reveal a nuanced relationship between external fields and quantum state behavior. By threading magnetic flux through the system, researchers observe a sensitivity in the phase of the expectation value of the translation operator, but only for states exhibiting delocalization; these states demonstrably ‘feel’ the imposed field. Conversely, localized states remain unaffected by the same flux, indicating an invariance to external magnetic influences. This dichotomy underscores a fundamental principle: the response of a quantum system to external perturbations is intrinsically linked to the extent of its spatial distribution, with delocalized systems serving as sensitive probes of external fields while localized states remain robust against them. This behavior provides a powerful tool for characterizing and understanding the nature of quantum confinement and its impact on system response.

Entanglement and Localization: A Quantum Future

The extent of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon where two or more particles become linked and share the same fate no matter how far apart, is intrinsically tied to a material’s localization length. This length, a measure of how confined an electron’s wave function is within a material, dictates the distance over which entanglement can be sustained. Materials exhibiting a large localization length allow for long-range entanglement, where correlations persist across macroscopic distances, potentially enabling robust quantum communication. Conversely, materials with a short localization length restrict entanglement to a localized region, resulting in short-range entanglement. This distinction isn’t merely theoretical; it fundamentally impacts the feasibility of building scalable quantum technologies, as maintaining entanglement over significant distances is paramount for practical applications like quantum computing and cryptography.

The ability to maintain quantum entanglement – a fragile correlation between particles – over substantial distances is paramount for the realization of practical quantum technologies. Sustained entanglement forms the backbone of quantum communication, enabling secure data transmission, and is essential for distributed quantum computing, where processing power is amplified by linking multiple quantum processors. However, entanglement is notoriously susceptible to environmental noise, leading to decoherence and signal loss. Therefore, a thorough understanding of factors influencing entanglement range, such as the localization length of quantum states, is not merely an academic pursuit; it directly dictates the feasibility and performance of future quantum networks and computational devices. Advancing this knowledge will allow researchers to engineer materials and protocols that preserve entanglement fidelity over greater distances, unlocking the full potential of these transformative technologies.

Continued investigation into the interplay between entanglement and localization length promises to reveal fundamental properties of quantum matter, potentially redefining current understandings of material behavior at the most basic level. This research isn’t merely theoretical; it actively fuels the development of next-generation quantum technologies. Specifically, a deeper comprehension of how entanglement sustains itself over distance is critical for building robust quantum computers, secure quantum communication networks, and highly sensitive quantum sensors. By manipulating the factors that govern entanglement – such as material properties and external stimuli – scientists aim to engineer quantum states with tailored characteristics, ultimately unlocking the full potential of these revolutionary devices and ushering in an era of quantum-enhanced technologies.

The research presented meticulously examines how the breaking of translation symmetry impacts the distribution of momentum and, consequently, the emergence of long-range entanglement. This investigation echoes Michel Foucault’s assertion: “Where there is power, there is resistance.” In this context, the broken symmetry represents a disruption of the ‘power’ of translational invariance, and the resulting long-range entanglement, measurable through the expectation value of the translation operator, can be understood as a form of ‘resistance’ – a non-local correlation arising from the system’s inability to remain invariant under translation. The paper’s core concept of linking momentum distribution to localization length demonstrates a rigorous analytical approach to quantifying this interplay, revealing the hidden structure within these complex systems.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The connection established between non-zero momentum expectation values and long-range entanglement when translation symmetry is broken presents a curious, if not entirely unexpected, result. The persistent reliance on Resta’s formula, while elegant, subtly begs the question of its limitations. How robust is this connection in higher dimensions, or for systems exhibiting more complex symmetry breaking patterns? The localization length, so readily linked to entanglement, remains a somewhat indirect measure. Future work might benefit from exploring direct probes of entanglement, circumventing the need to infer it from spatial characteristics.

A pressing issue is the practical application of this formalism. While mathematically satisfying, translating these findings into a reliable diagnostic for entanglement in realistic, strongly-correlated materials is not trivial. The assumption of a well-defined momentum space, for instance, may not always hold. One wonders if the observed connection is merely a consequence of the specific mathematical tools employed, or if it reflects a deeper, underlying physical principle.

Ultimately, this work shifts the focus from finding entanglement to characterizing it in systems where traditional methods falter. The challenge now lies in expanding the toolkit-and, perhaps more importantly, refining the questions being asked. Is long-range entanglement simply a byproduct of broken symmetry, or does it play a more active role in determining the system’s emergent properties?

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15345.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- The 10 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Enterprise

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- How to Build a Waterfall in Enshrouded

2026-01-23 16:58