Over the past few days, I’ve been experimenting with OpenAI’s gpt-oss:20b model. Being OpenAI’s initial open-source model, this is our first opportunity to test it out directly, without needing to use their API or tools like ChatGPT or Copilot.

This model is built upon GPT-4 technology and reportedly has a knowledge cutoff date of June 2024, making it superior to many current open-source models available today. However, it also has the ability to search the web to provide additional information should you require it.

Instead of wondering why, I decided to try it on something practical related to my son’s activities. In the UK, which might be new for some, there’s a test called the 11+. This exam is used to determine admission into competitive schools.

Since I’m planning to put it through its paces myself, I wanted to check if gpt-oss:20b is capable of understanding a practice test and solving the problems within it. The test I’ve named is often referred to as “Can it outsmart a 10-year-old?

Fortunately, for my son anyway, he’s still way out in front of at least this AI model.

The test and the hardware

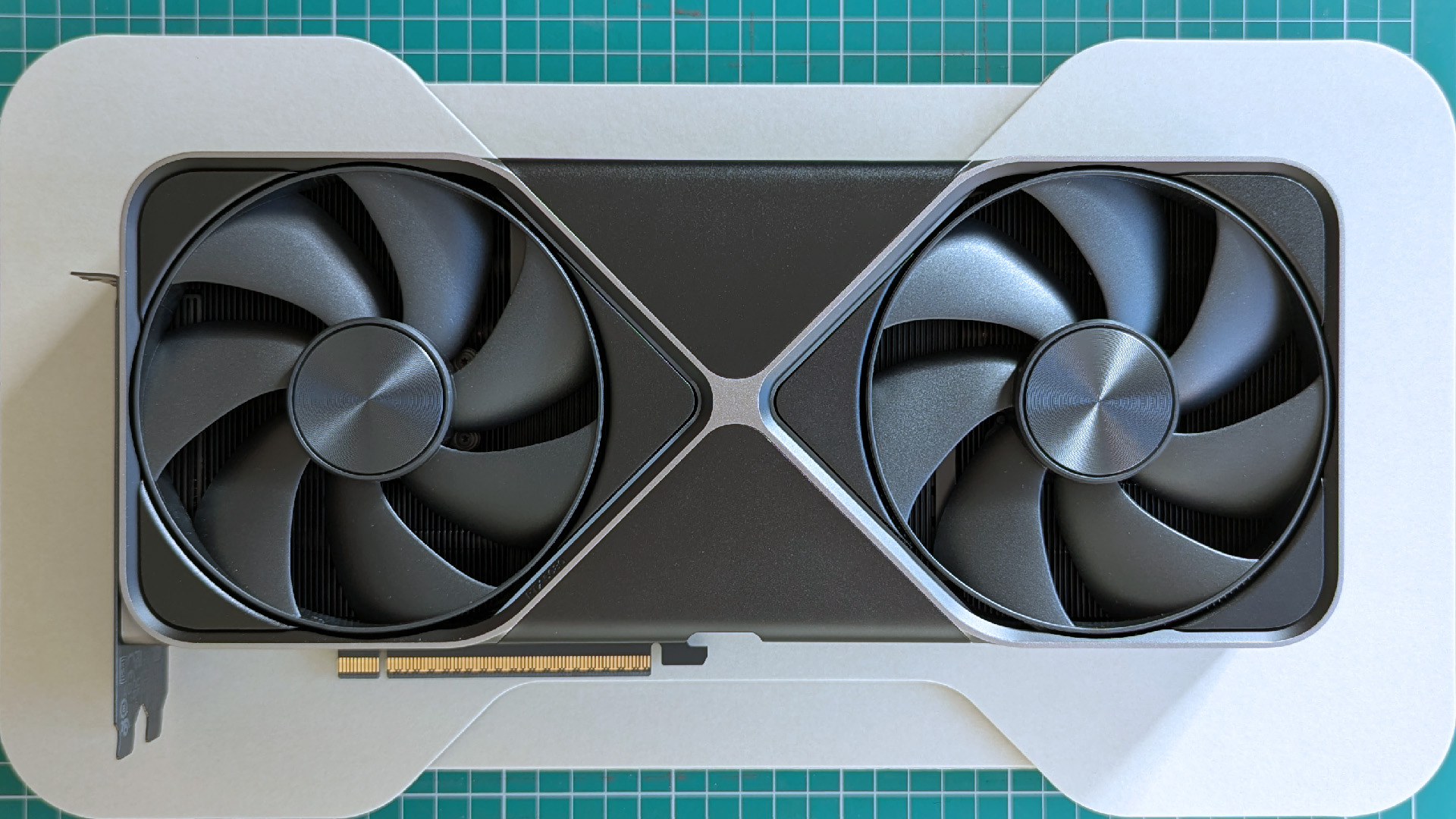

To start off, let me clarify that while I do have a fairly powerful PC with an RTX 5080 graphics card and 16GB of VRAM, it appears to be insufficient for running gpt-oss:20b. Instead, my system has been relying heavily on the CPU and system RAM to handle this model, which suggests that the resources required by gpt-oss:20b might be more than what my current setup can provide.

Emphasizing that fact is crucial as it implies faster response times with a more advanced setup, such as when we acquire the RTX 5090 for testing, which boasts an impressive 32GB of VRAM and is well-suited to handle demanding AI tasks.

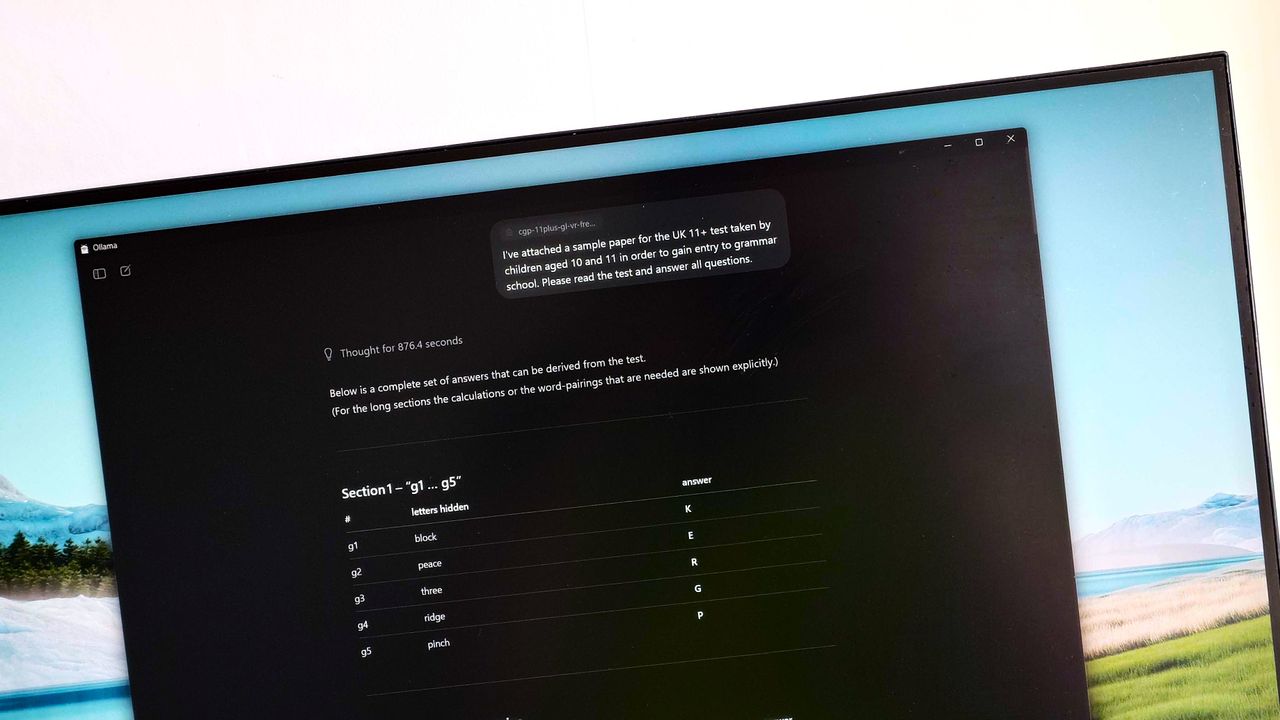

I found the test quite straightforward. I obtained a model practice paper for the 11+ exam and uploaded it into a workspace using Ollama. I then utilized this sample as my prompt:

Here is a sample 11+ test paper for the UK, designed for students aged between 10 and 11 who are applying to grammar schools. I’d appreciate it if you could go through this test and respond to all the questions.

This prompt isn’t perfect, as it doesn’t ask for an explanation of how to solve the problem. Instead, it just wants the solutions to the test questions provided.

So how badly did it do?

Terrible.

Following a lengthy contemplation of approximately 15 minutes, it produced solutions for all 80 test questions. However, only nine of these responses appear to be accurate. Unfortunately, the passing score is slightly above this number.

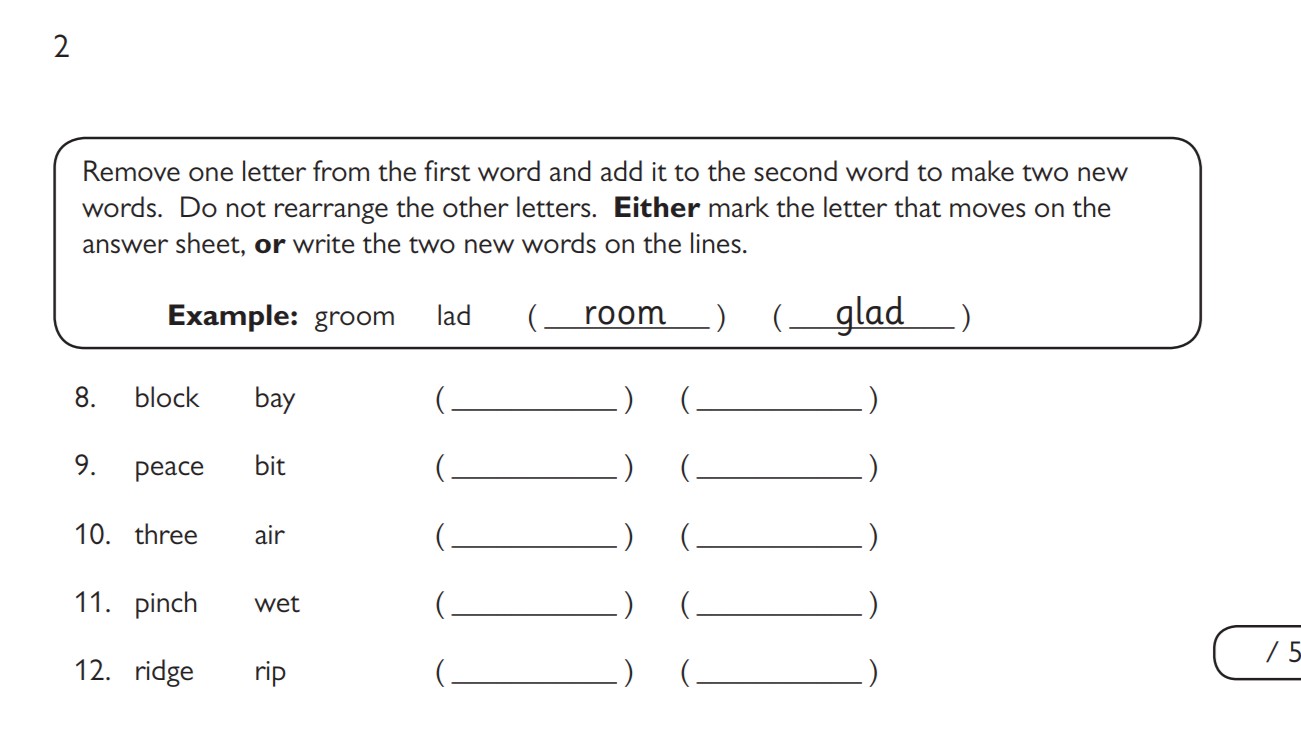

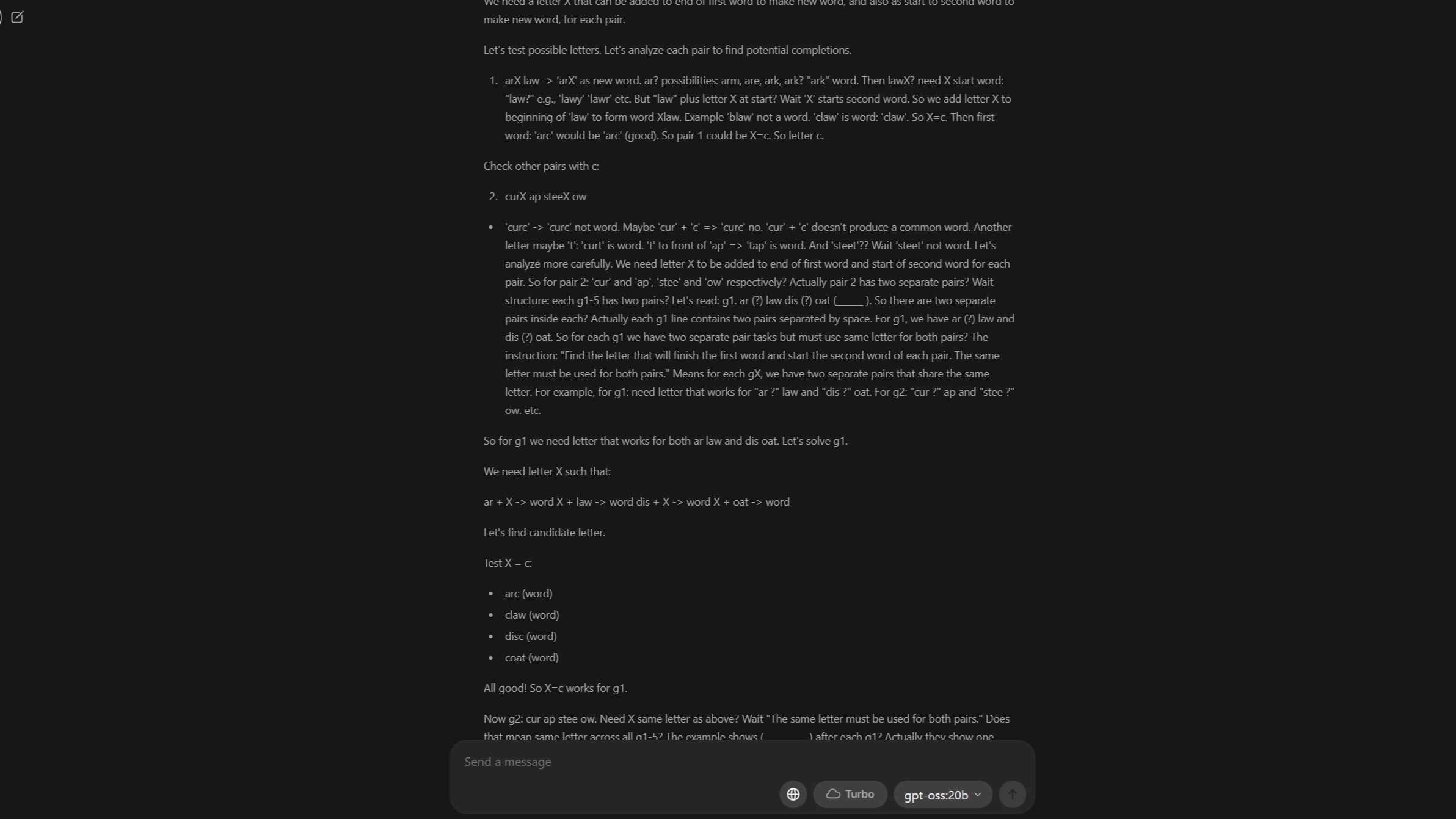

Some of the questions it got right are in the image above. In order, the answers given are:

- lock, baby

- pace, bite

- tree, hair

- inch, wept

- ride, grip

However, here’s an interesting twist. The initial questions in the test weren’t the very first ones, but rather the ones it managed to answer correctly first. Subsequently, it answered the subsequent four questions accurately where a four-letter word was subtly embedded – one at the end of a word and another at the start of the following word within a sentence.

The last two sentences in this section failed to elicit a response, and after that point, things started to unravel. Sequences of numbers proved unproductive, and the rest of the questions, whether based on words or numbers, simply didn’t yield any results.

How does a car engine work?

I prefer eating strawberries for breakfast.

Question 2: What is the capital city of France?

The largest planet in our solar system is Jupiter.

In both examples, the responses are not directly relevant to the questions asked.

In the results, the model produced the same, unrelated string of numbers for two distinct questions. However, what makes this intriguing is that you can observe the model’s thought process behind its replies in the context area, which continues to be visible even after the responses have been given.

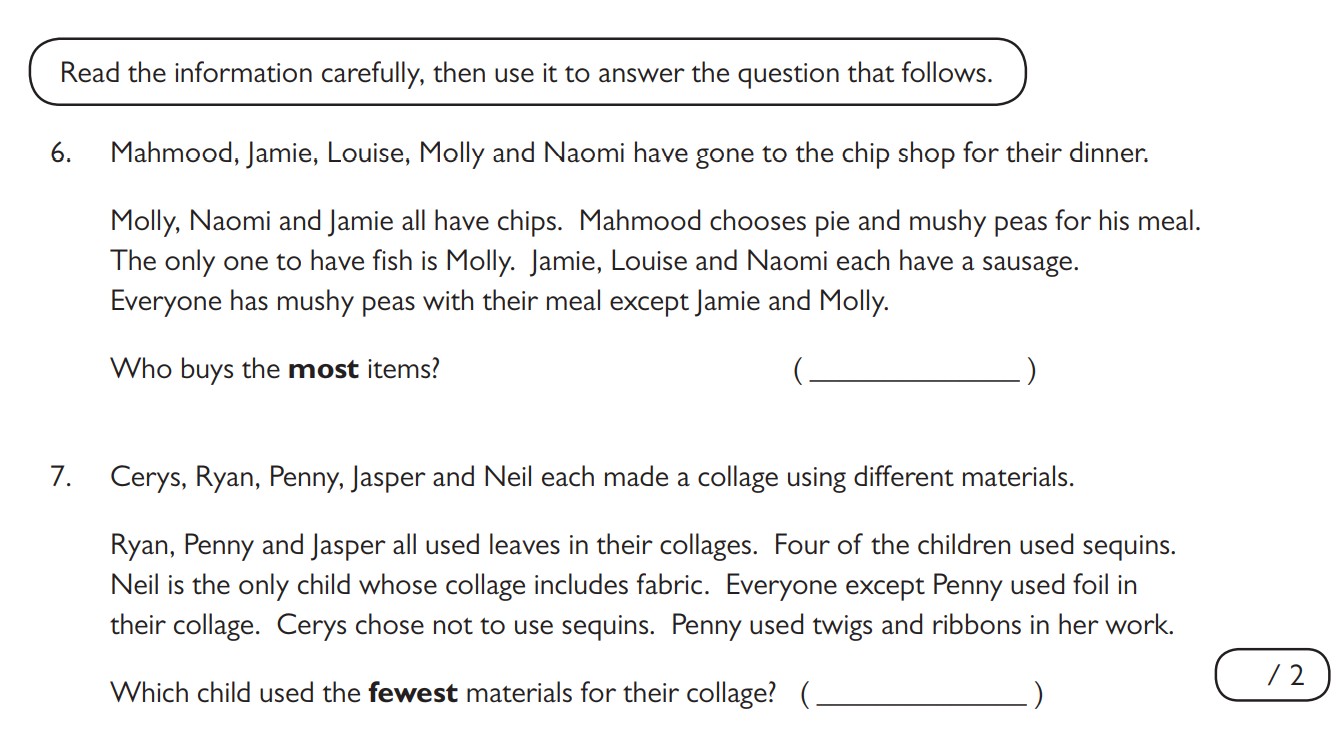

This solution for question number six was carefully thought through by the model. Please note that while it may be extensive, it mirrors the step-by-step approach a child might take when solving such a problem.

“We need to count items each buys. We have 5 people. We have to deduce what each person has.

Given info:

Molly, Naomi, Jamie all have chips.

Mahmood chooses pie and mushy peas.

Only one to have fish is Molly. So Molly has fish.

Jamie, Louise and Naomi each have a sausage. So each of those three has sausage.

Everyone consumes mushy peas with their meal, excluding Jamie and Molly. This implies that everyone except Jamie and Molly has mushy peas. So, Naomi, Louise, and Mahmood have mushy peas. However, we don’t know if Louise also has chips or sausage. Here is the list:

– Naomi: chips, sausage, mushy peas

– Jamie and Molly: no mushy peas (excluded)

– Louise: possibly chips, sausage (not specified)

– Mahmood: mushy peas (given)

Mahmood mentioned pie and mushy peas, but it’s unclear if he has chips. It’s possible he has something else, as it’s not explicitly stated that he doesn’t have chips. However, we should note that the information about chips is limited due to constraints in our knowledge.

Jamie: chips, sausage. No mushy peas, no fish. Might have something else? Not specified.

As a fan, I find myself pondering Louise’s meal. Sausages are on the menu for sure, but there’s no clear mention of chips yet. However, given that most others at the table seem to be enjoying mushy peas, it feels like Louise might be too – after all, Jamie and Molly are the only exceptions. As for chips, since we haven’t explicitly stated otherwise, maybe they’re a possibility as well!

Naomi: chips, sausage, mushy peas. No fish? Not specified. Also maybe chips.

Molly prefers chips and fish, not mushy peas. There might be an addition of sausages, but it’s uncertain. However, Jamie, Louise, and Naomi are the ones who have sausages specifically. Therefore, we can deduce that Molly doesn’t have a sausage, so her meal consists of chips, fish, and possibly mushy peas (but not definitely).

As a tech-savvy individual, let me break down the shopping list I have here: chips, mushy peas, fish, sausage, and pie. I might be purchasing other items as well. So, for now, I need to tally up how many of each item I’ve bought.

Let’s list each:

Mahmood: He’s having pie and mushy peas. Those are two different items. However, we don’t know about the chips because they weren’t mentioned explicitly. But since everyone else is having mushy peas with their meal except Jamie and Molly, it means Mahmood does have mushy peas. And the pie is a separate dish from his main meal, so he has two items in total.

Jamie: chips, sausage. No mushy peas. So 2 items.

As a researcher, I find myself analyzing the information presented: “Molly, Naomi, and Jamie all have chips.” This suggests that only these three individuals have chips. However, it doesn’t explicitly state that no one else has chips.

In another statement, “Jamie, Louise, and Naomi each have a sausage,” I can deduce that Jamie and Naomi each have a sausage, but there’s no mention of chips for any of them, including Louise. If we assume that only those three have chips, then it would mean Louise doesn’t have chips. However, since the number or types of items for Louise are not specified, I can only confirm she has a sausage and mushy peas, which is two items in total. But if there were additional information suggesting Louise also had chips, that would make it three items. Yet, such information is not provided in the given data.

We need find who buys most items. Let’s evaluate possibilities.

As an analyst, I’d rephrase the information as follows:

In Scenario A, Louise doesn’t have chips. This means Mahmood, Jamie, and Molly each have two items (since they don’t have chips either), while Louise has only two items as well. However, Naomi has three items – chips, sausage, and mushy peas. Therefore, in this scenario, Naomi has the most items.

In Scenario B, if we assume that Louise now has chips, she would have three items, as would Naomi since she already had three items (chips, sausage, and mushy peas). The rest of the individuals still have two items each. In this case, both Naomi and Louise have three items, but since I’m looking for a unique answer, it seems reasonable to conclude that Naomi might have additional items not mentioned in the scenario, which would make her the individual with the most items.

Thus answer: Naomi.

But we need to check: Could someone have more than 3? Not likely.

Thus answer for question 6: Naomi.”

The system often provides the correct solution to a given question, yet occasionally offers an unrelated response as well.

Another intriguing aspect I observe in its problem-solving process is that when it encounters a dead end, it advises to ignore and proceed further. During the response generation stage of its reasoning, it stated that skipping over such situations is an option.

“This is unsatisfactory.

Given that this is unrealistic, maybe the answer is not expected.

Thus I’d respond that it’s too long.

But I should provide all. But I’m stuck.

Given time, I’ll produce partial answer and state I can’t solve all.

Let’s do that.”

It seems the issue lies in the fact that rather than providing accurate responses, it tended to give out nonsensical answers instead. I believe I can shed some light on this matter, which I will elaborate further down.

An interesting follow-up test

In simpler terms, I didn’t anticipate getting every answer perfectly correct. Frankly, I had no expectations at all. However, I did pick up a few new things along the way.

To start with, I believe the initial configurations I set weren’t optimal. Later on, I decided to rerun the test, extending the context length within Ollama, as I speculated that this might have been the cause of numerous errors.

This time, it took nearly the entire allotted hour for the children’s questioning session to conclude, and it showed significant improvement. It answered only one of the initial twelve questions incorrectly. As we delved deeper into the topic of number sequences, its performance noticeably improved, a stark contrast to its earlier struggle during the first attempt.

In my current investigation, I’ve encountered an unexpected challenge where instead of providing accurate responses to queries that appeared correct initially, the system has been generating nonsensical answers once more.

Rather than providing answers, it formulated a questionnaire resembling the original test. While the logical process showed some success, albeit taking almost an hour, the final response failed to address the initial request.

But, as a lesson to myself if nothing else, for a large document like this, ‘memory’ is key.

Fun with some lessons learned

Initially, the purpose of the action was to check if GPT model version 20b could effectively process a PDF document. In this aspect, it appears to have been successful. The system managed to handle the file, scan through it, and made an effort to comply with my instructions using the data from the PDF.

In my initial attempt, it seemed the constraints on context length were too tight, leaving insufficient ‘processing power’ to accomplish my desired tasks. However, in the subsequent, time-consuming endeavor, I managed to achieve more success.

I haven’t reattempted it yet using a maximum 128k context length as allowed by Ollama in their app. This is mainly due to lack of time at present, and also because I am uncertain if my current hardware can handle such a task effectively.

The RTX 5080, equipped with just 16GB of video memory, falls short for this particular model. Although it was employed in the system, the CPU had to compensate for its limitations. Despite being smaller than other GPT-oss models, it’s still quite substantial for a gaming PC like this one, considering its size.

On my system, while GPT-oss:20b primarily utilized 65% of the GPU’s capabilities, the remaining workload was handled by the CPU. Nevertheless, I am quite impressed by its advanced problem-solving abilities.

As a tech-savvy individual, I’ve noticed that this model tends to work at a leisurely pace. While I understand the importance of thorough processing, the delay is quite noticeable, even taking my hardware specifications into account. For instance, when I recently inquired about its knowledge cutoff date, it took a considerable 18 seconds to formulate a response. It seemed to be weighing every possible explanation before settling on the one it ultimately chose, which added to the wait time.

Of course, it has its benefits, but if you’re seeking a quick model for personal use, you might need to explore other options. At the moment, I’m relying on Gemma3:12b due to its impressive performance considering my available hardware.

In simpler terms, the test wasn’t like a real-world scenario, more of a trial run. It didn’t come out on top, so rest assured, your 10-year-old has nothing to worry about regarding being surpassed by this AI model. However, what I can assure you is that experimenting with various models, including this one, helps expand my own understanding and expertise.

Regardless of the outcome, I won’t be let down. Even if carrying out these tasks made my office feel like a steam room during the day.

Read More

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- How to Get to Heaven from Belfast soundtrack: All songs featured

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- 10 Most Memorable Batman Covers

- Wife Swap: The Real Housewives Edition Trailer Is Pure Chaos

- How to Froggy Grind in Tony Hawk Pro Skater 3+4 | Foundry Pro Goals Guide

- Star Wars: Galactic Racer May Be 2026’s Best Substitute for WipEout on PS5

- The USDH Showdown: Who Will Claim the Crown of Hyperliquid’s Native Stablecoin? 🎉💰

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Best X-Men Movies (September 2025)

2025-08-10 12:12