Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how the unique spectral properties of quasiperiodic lattices govern the flow of electrons, leading to unexpected transport phenomena.

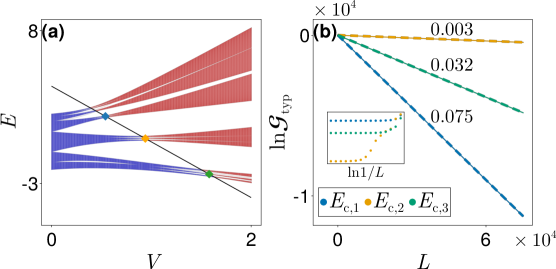

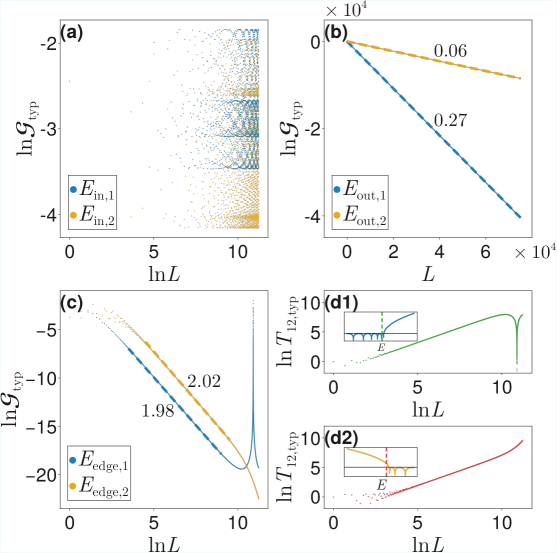

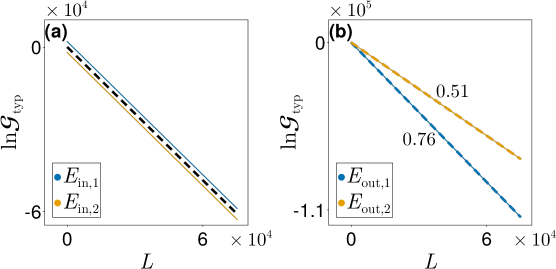

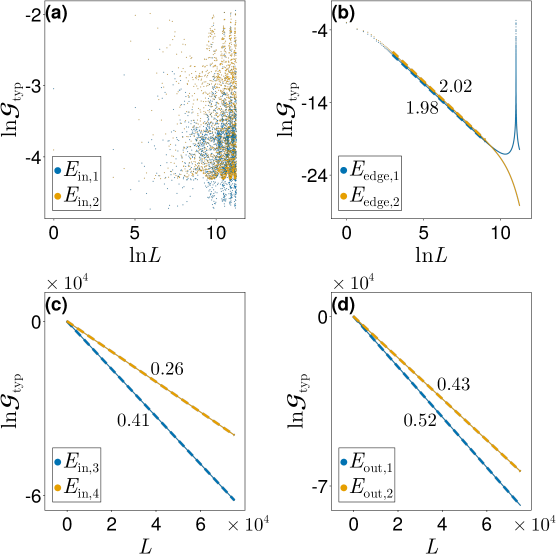

The study demonstrates a connection between mobility edges, band edges, and emergent exceptional points in quasiperiodic systems, revealing universal scaling laws and locating the analytical mobility edge within a spectral gap of the GAAH model.

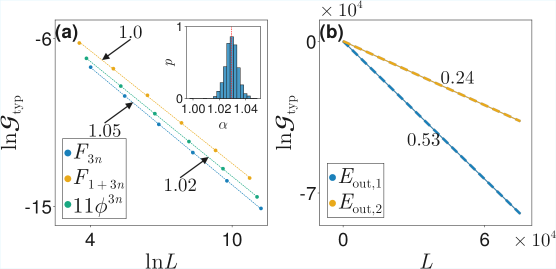

While conventional models struggle to fully capture transport phenomena beyond periodic or disordered systems, this work-Anomalous transport in quasiperiodic lattices: emergent exceptional points at band edges and log-periodic oscillations-investigates quantum transport in the Aubry-André-Harper model, revealing a direct link between spectral characteristics and conductance scaling. Specifically, we demonstrate universal subdiffusive transport at band edges due to emergent exceptional points and log-periodic conductance oscillations in the critical phase, arising from discrete scale invariance. Furthermore, our analysis of the generalized Aubry-André-Harper model suggests the mobility edge resides within a finite spectral gap, leading to counterintuitive conductance suppression-but what broader implications do these findings hold for designing materials with tailored transport properties?

The Erosion of Periodic Order: A Foundation for Novel Behavior

Conventional solid-state physics relies heavily on the assumption of perfect periodicity within a material’s crystalline structure, simplifying calculations and predictions of electronic behavior. However, a growing number of real-world materials defy this neat arrangement, exhibiting instead quasiperiodic order – a structure that is ordered but not strictly repeating. These materials, such as certain metallic alloys and quasicrystals, possess long-range order without the translational symmetry found in traditional crystals. This departure from periodicity fundamentally alters the electronic landscape, creating energy bands that are not the smooth, continuous structures predicted by the Bloch theorem, and opening pathways for novel and often counterintuitive physical properties. The prevalence of quasiperiodic order highlights a limitation in standard models and necessitates the development of new theoretical frameworks to accurately describe the behavior of these fascinating materials.

The departure from strict periodic order in quasiperiodic structures fundamentally alters a material’s electronic behavior, creating properties that defy prediction based on conventional solid-state physics. Established transport theories, such as those reliant on the Bloch theorem-which describes electron behavior in perfectly periodic lattices-break down when confronted with the inherent aperiodicity. Electrons in these systems do not experience a consistent, repeating potential, leading to phenomena like critical wave functions and the potential for both metallic and insulating behavior within the same material. This challenges the traditional understanding of conductivity and introduces the possibility of novel electronic devices exploiting these unique, aperiodically-driven characteristics, demanding a re-evaluation of how electrons move and interact within complex materials.

The conventional understanding of electron behavior in solids relies heavily on the Bloch theorem, which describes wave-like propagation through a perfectly periodic lattice. However, quasiperiodic materials-those exhibiting order without strict repetition-invalidate this foundational principle. Consequently, electrons in these systems don’t behave as freely propagating waves; instead, they experience strong localization effects, becoming trapped within specific regions of the material. This localization arises from the intricate interference patterns created by the aperiodic structure, disrupting the long-range coherence necessary for conventional conduction. Advanced theoretical models, incorporating concepts like Anderson localization and fractal dimensions, are therefore crucial to accurately describe charge transport in these materials, predicting behaviors drastically different from those observed in their periodic counterparts-including a transition from metallic to insulating states even without bandgap formation and the emergence of unique scaling laws for conductivity.

The Aubry-Andre-Harper Model: A Simplified Lens on Aperiodicity

The Aubry-Andre-Harper (AAH) model is a one-dimensional tight-binding model defined by the Hamiltonian H = \sum_{n} \epsilon_n c^\dagger_n c_n + \sum_{n} (t c^\dagger_n c_{n+1} + t^* c^\dagger_{n+1} c_n) , where \epsilon_n = \lambda \cos(2\pi \alpha n) represents the on-site potential, α is an irrational number, λ is the potential strength, and t is the hopping parameter. This model describes the behavior of electrons in a quasiperiodic potential, differing from periodic lattices by the aperiodicity introduced by α. The resulting energy spectrum exhibits a Cantor set structure, indicating the presence of localized and extended states depending on the value of λ. It serves as a simplified, analytically tractable system for understanding the broader class of quasiperiodic systems and has been instrumental in exploring concepts like Anderson localization in aperiodic potentials.

Analysis of the Aubry-Andre-Harper (AAH) model relies heavily on numerical methods, particularly the Transfer Matrix Formalism (TMF) and the Periodic Approximation. The TMF allows for the efficient calculation of the system’s transmission and reflection coefficients, enabling determination of the energy spectrum and localization properties. The Periodic Approximation, employed to simplify calculations, assumes that the potential exhibits periodicity over a large number of lattice sites; while an approximation, it provides a computationally tractable approach for investigating systems with quasiperiodic potentials. These techniques are used to calculate the Lyapunov exponent, which characterizes the rate of divergence of wavefunctions and thus indicates localization or extended behavior, and to map out the phase diagram distinguishing localized and extended states in the AAH model.

The standard Aubry-Andre-Harper (AAH) model, while foundational for investigating quasiperiodic systems, presents a limitation in its fixed parameterization which prevents external control over the phase transition between localized and extended electron states. This inflexibility spurred research into modified and generalized models capable of tuning this transition. Variations introduce adjustable parameters, such as on-site potential differences or hopping amplitudes, allowing researchers to systematically investigate the behavior of electrons near the mobility edge and explore the influence of potential landscapes on localization phenomena. These tunable models provide a more complete platform for studying the relationship between disorder, dimensionality, and the emergence of both localized and extended states in quasiperiodic lattices.

Pinpointing the Threshold: The Emergence of Mobility Edges

The Generalized Anderson Model (GAM), an extension of the original Anderson model, introduces a tunable parameter – typically a disorder strength W or a binary potential depth – that generates a mobility edge within the energy spectrum. This mobility edge demarcates the transition between localized and extended states; states below a certain energy exhibit exponential decay, indicating localization, while states above this energy demonstrate a linear divergence of their wavefunctions, signifying extended behavior. The precise location of the mobility edge is determined by the value of the introduced parameter and governs the system’s overall conductivity; increasing the disorder W generally lowers the mobility edge, reducing the range of energies supporting extended states and thus decreasing conductivity.

The transition between insulating and conducting behavior at the mobility edge is a direct consequence of the change in electronic states. Below the mobility edge, states are localized, meaning electrons are confined to specific regions and unable to contribute to current flow, resulting in insulating behavior. Conversely, above the mobility edge, states become extended, allowing electrons to propagate throughout the material. This propagation facilitates charge transport, leading to conducting behavior. The conductivity, therefore, increases as the energy level crosses the mobility edge, demonstrating a clear correlation between the nature of electronic states and the material’s ability to conduct electricity.

The identification of extended states within the Generalized Anderson Model is quantitatively verified through calculation of the Lyapunov Exponent. This exponent measures the average rate of divergence of initially nearby wavefunctions, and a positive value definitively indicates the presence of extended states capable of conducting electricity. Specifically, the Lyapunov Exponent, denoted as λ, is determined by analyzing the long-distance behavior of the wavefunction and quantifying its exponential growth. A zero or negative λ confirms localization, while a positive value demonstrates that the wavefunction spreads throughout the system, characteristic of extended states and conductive behavior.

Beyond Diffusion: Anomalous Transport and the Role of Symmetry

Conventional understanding of material transport, often described by the Drude model, predicts a linear relationship between displacement and time – a process known as diffusion. However, investigations into quasiperiodic systems – structures lacking the translational symmetry of crystals, yet possessing long-range order – reveal a strikingly different phenomenon. These systems frequently exhibit subdiffusion, where particle displacement grows more slowly than linearly with time, suggesting a hindered or fragmented movement. This anomalous transport isn’t simply a slowing of diffusion, but a fundamentally different process characterized by localization effects and a scaling exponent less than one in the mean-squared displacement. The deviation from Drude-like behavior indicates that the standard kinetic theory fails to accurately describe particle dynamics in these aperiodic, yet ordered, environments, prompting researchers to explore alternative theoretical frameworks to explain the observed transport properties.

The peculiar transport behavior observed in certain quasiperiodic systems isn’t simply a matter of increased scattering; it fundamentally arises from the system’s Hamiltonian possessing what are known as Exceptional Points. These are singularities in the parameter space where two or more eigenstates coalesce, leading to a breakdown of traditional Hermitian symmetry. At these points, the usual correspondence between eigenvalues and eigenvectors fails, and the system becomes exquisitely sensitive to perturbations. Consequently, energy can ‘funnel’ through these points, drastically altering the flow of electrons or other transported particles. This creates a non-diffusive regime where transport is significantly slowed – a subdiffusive process – and the system’s response is governed not by typical scattering rates, but by the proximity and characteristics of these Exceptional Points within its energy landscape. The existence of these points offers a new lens through which to understand and potentially control transport phenomena in complex materials.

Analyzing the peculiar transport phenomena in quasiperiodic systems requires sophisticated theoretical approaches, and the synergy between Non-Equilibrium Green’s Function (NEGF) techniques and the Landauer Conductance Formula has proven remarkably effective. NEGF allows researchers to model systems far from thermal equilibrium, crucial for understanding current flow, while the Landauer Formula elegantly connects conductance to the transmission probability of electrons through the system. This combination provides a framework to calculate how electrons scatter and propagate, even in the presence of disorder or exceptional points within the Hamiltonian. By directly linking microscopic quantum mechanical properties to macroscopic measurable quantities like conductance, this methodology not only elucidates the mechanisms behind anomalous transport – such as subdiffusion – but also enables predictive modeling of novel materials exhibiting similar behaviors. The resulting insights are vital for designing materials with tailored electronic properties and exploring the fundamental limits of conductivity.

The study of anomalous transport within quasiperiodic lattices reveals a compelling interplay between structure and emergent behavior. It observes how seemingly minor alterations to the lattice – the arrangement of its components – drastically influence the flow of quantum particles. This resonates deeply with Wittgenstein’s observation: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” The ‘world’ here is the quasiperiodic system, and the ‘language’ its structural parameters. Altering these parameters-creating spectral gaps or manipulating band edges- fundamentally reshapes the observed transport characteristics, demonstrating that understanding the whole system is paramount, not merely isolating individual components. The identification of universal scaling laws underscores that even complex systems exhibit underlying order, a principle echoing the search for logical structures within language itself.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstrated connection between spectral features and transport in quasiperiodic lattices, while revealing universal scaling, merely clarifies the contours of a deeper complexity. The analytical mobility edge, comfortably situated within the observed spectral gap of the GAAH model, suggests a fragility in its predictive power when applied to systems further removed from ideal aperiodicity. The insistence on simplicity, on elegant design, demands acknowledgement that real materials introduce perturbations – disorder, interactions – which inevitably disrupt the neat correspondence between band structure and conductance.

Future inquiry must address the limits of this correspondence. How robust are these scaling laws when confronted with even minor deviations from perfect quasiperiodicity? The identification of exceptional points at band edges, while intriguing, presents a challenge: are these points merely mathematical curiosities, or do they herald genuinely novel transport phenomena exploitable in device architectures? The study of non-Hermitian effects, and the interplay between topology and localization, feels particularly crucial.

Ultimately, the pursuit of understanding in these systems requires a shift in perspective. The focus should move beyond simply mapping spectral characteristics onto transport behavior, and toward understanding the emergent properties arising from the interaction of these features. A holistic view, recognizing the system as an integrated whole, is paramount. For it is in the interplay, in the delicate balance of order and disorder, that true complexity, and perhaps genuine innovation, resides.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10056.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Silent Hill 2 Leaks for Xbox Ahead of Official Reveal

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- USD JPY PREDICTION

- Auto 9 Upgrade Guide RoboCop Unfinished Business Chips & Boards Guide

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

2026-01-18 18:54