Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research explores how hot, dense matter and magnetic fields affect the stability of heavy quarkonium particles.

This review investigates medium-induced dissociation of quarkonia at finite chemical potential and weak magnetic field, finding temperature to be the dominant influence.

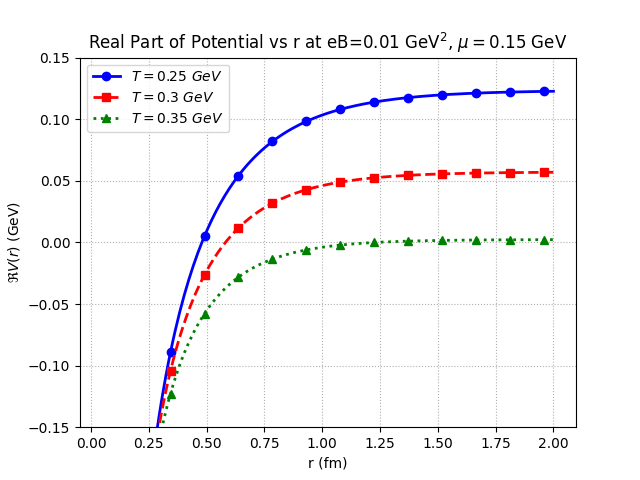

Understanding the behavior of matter at extreme temperatures and densities-as created in heavy-ion collisions-remains a central challenge in quantum chromodynamics. This work, ‘Medium-Induced Quarkonium Dissociation at Finite Chemical Potential and Weak Magnetic Field’, investigates how these conditions affect heavy quarkonium, bound states of heavy quarks, by modeling interactions within the quark-gluon plasma. Our results demonstrate that while finite chemical potential and weak magnetic fields subtly modify quarkonium properties, temperature is the dominant factor governing dissociation through Debye screening and thermal decay. Could a more precise understanding of these dissociation mechanisms refine our interpretation of experimental data from relativistic heavy-ion collisions and provide further insight into the properties of strongly coupled matter?

From Hadronic Matter to a Very Transient State

At temperatures exceeding trillions of degrees – conditions mimicking those shortly after the Big Bang and found within neutron stars – ordinary matter transforms into a remarkable state known as quark-gluon plasma (QGP). Normally, quarks and gluons, the fundamental constituents of protons and neutrons, are confined within these particles by the strong nuclear force. However, at extreme densities and temperatures, this confinement breaks down, liberating quarks and gluons into a collective, deconfined state. This transition represents a phase change, much like water turning into steam, but far more fundamental, altering the very building blocks of matter. Instead of discrete particles, the QGP behaves as a fluid of interacting quarks and gluons, exhibiting unique properties that distinguish it from any known form of matter and providing physicists with a window into the strong force itself.

To investigate the transition from hadronic matter to quark-gluon plasma, scientists employ ultra-relativistic heavy-ion collisions. Facilities like the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) accelerate nuclei to near light speed and collide them, recreating the extreme temperatures and densities thought to have existed in the early universe. These collisions don’t simply shatter the nuclei; instead, they momentarily generate the QGP, allowing researchers to study its properties by observing the thousands of particles produced in the aftermath. By meticulously analyzing the types, energies, and angular distributions of these particles, physicists can infer the characteristics of the QGP itself, essentially using the collision debris as a window into this exotic state of matter. This approach, combining experimental data with theoretical models, provides crucial insights into the fundamental nature of strong interactions and the behavior of matter under the most extreme conditions.

The quark-gluon plasma (QGP), created in high-energy collisions, defies simple categorization as just an extremely hot gas. Instead, it exhibits collective behavior dictated by properties like dielectric permittivity – a measure of how the plasma responds to electric fields. This permittivity isn’t merely a passive characteristic; it dramatically reshapes the forces experienced by particles traversing the QGP. Unlike a conventional gas where particles interact weakly, the QGP’s permittivity screens the strong force, effectively reducing the interaction strength between color-charged quarks and gluons. This ‘screening’ alters how jets of particles are produced and propagate, and influences the overall pressure exerted by the plasma, leading to phenomena such as enhanced collective flow and modified particle spectra. Consequently, understanding the QGP requires a sophisticated treatment that goes beyond the assumptions of simple thermal models, acknowledging its complex and dynamically evolving electromagnetic properties.

The quark-gluon plasma (QGP) doesn’t simply offer a hotter environment for particles; it actively reshapes how those particles interact. Within this deconfined state of matter, the strong force, normally binding quarks within hadrons, operates differently, effectively changing the dielectric permittivity of the medium. This altered landscape dramatically influences the propagation of particles traversing the QGP; what would normally be a straight-line path becomes curved and distorted due to interactions with the surrounding quarks and gluons. Consequently, high-energy particles experience significant modifications to their momentum and energy loss, manifesting as “jet quenching” – a suppression of energetic jets observed in heavy-ion collisions. The degree of this quenching provides crucial insight into the density and collective properties of the QGP, allowing scientists to map out its intricate structure and understand the fundamental forces at play in extreme conditions.

Heavy Quarkonia: Probing the Transience

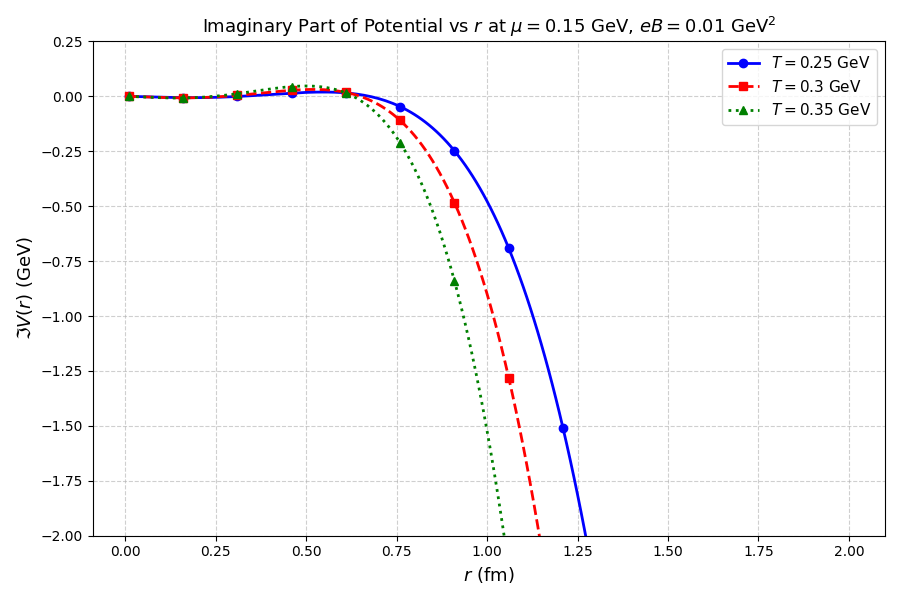

Heavy quarkonia, bound states consisting of a heavy quark (charm or bottom) and its antiquark, function as effective probes of the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) due to their inherent characteristics. Their relatively large physical size – on the order of a few femtometers – means they interact with the QGP over a significant distance, experiencing collective effects. Furthermore, the internal structure of quarkonia, characterized by a binding potential between the quarks, is susceptible to modifications within the dense QGP environment. These modifications, specifically the suppression or alteration of quarkonium states, provide information about the temperature, density, and transport properties of the medium they traverse. The sensitivity arises from the fact that the QGP effectively screens the color force binding the quark and antiquark, potentially leading to dissociation or modification of the quarkonium’s mass and decay rates.

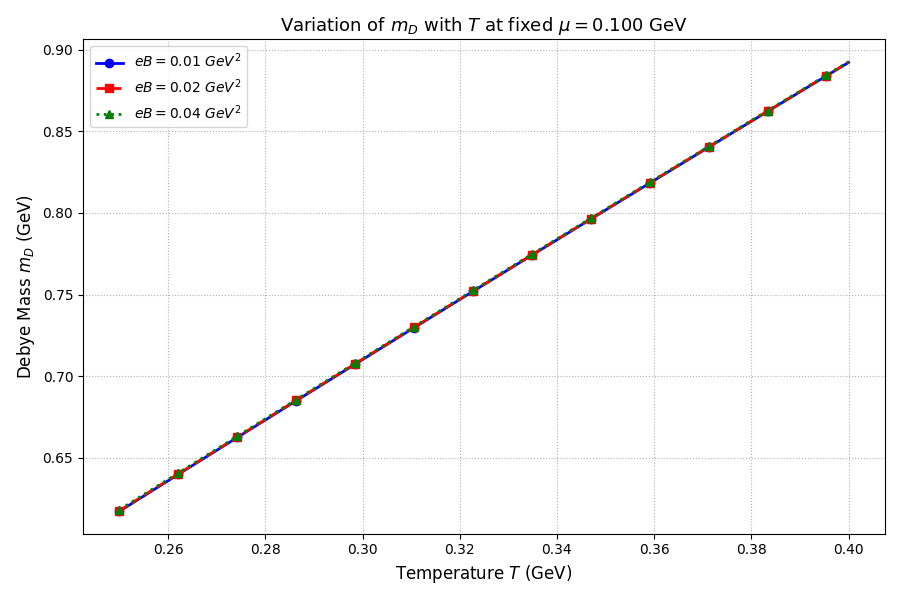

The Debye screening effect, a fundamental property of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP), suppresses the strength of the Coulomb interaction between heavy quarks bound within quarkonia. This suppression arises from the increased density of color charges in the QGP, which effectively shields the interaction. As the temperature of the QGP increases, the Debye screening length decreases, further weakening the potential between the quarks. When the potential becomes insufficient to bind the quarkonium state, dissociation occurs, leading to a reduction in quarkonium yields at high energies. The degree of screening, and therefore the dissociation temperature, is dependent on the temperature and composition of the QGP, making quarkonia sensitive probes of the medium’s properties.

Effective theoretical descriptions of heavy quarkonia rely on frameworks designed to handle the interplay between relativistic and non-relativistic effects. Non-Relativistic QCD (NRQCD) treats heavy quarks as non-relativistic, allowing for perturbative calculations of production and decay rates, while incorporating short-distance physics through Wilson coefficients. Potential Non-Relativistic QCD (pNRQCD) further simplifies the description by integrating out short-distance modes, resulting in an effective potential that describes the interaction between the heavy quarks. This approach enables the calculation of quarkonium properties, such as energy levels and decay widths, and facilitates the study of medium modifications within the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) by incorporating screening effects into the potential.

Lattice QCD calculations offer a first-principles method for determining quarkonium spectral properties and dissociation temperatures within the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). These calculations reveal a hierarchy of dissociation temperatures among different quarkonium states; specifically, the J/ψ meson exhibits the lowest dissociation temperature among those studied, while the Υ(1S) state displays the highest. This disparity indicates that the J/ψ is more readily dissociated by the QGP than the Υ(1S), demonstrating differing sensitivities to the QGP’s thermal environment and providing a means to map the QGP’s temperature and density profiles.

Calculating Interactions: A Dance with Complexity

Calculating the potential between heavy quarks within the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) presents significant theoretical challenges due to the strong coupling and non-perturbative nature of the interactions. Traditional perturbative methods are inadequate; therefore, advanced techniques like the Hard Thermal Loop (HTL) approximation are necessary. The HTL approximation incorporates the effects of thermal fluctuations and medium interactions on the propagators of the involved particles, effectively resumming a class of diagrams that would otherwise be intractable. This approach modifies the Debye mass, accounting for the screening of the color force within the QGP, and allows for the calculation of quantities like the static potential and dielectric permittivity to a higher degree of accuracy than simpler approximations. The complexity arises from the need to handle an infinite number of loop diagrams, requiring careful regularization and renormalization procedures within the HTL framework to obtain physically meaningful results.

The Hard Thermal Loop (HTL) approximation enables the computation of the one-loop resummed gluon propagator by incorporating thermal fluctuations within the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP). This propagator, denoted as D_{\mu\nu}(q), accounts for the self-energy corrections to the gluon due to interactions with other gluons and quarks in the thermal medium. Calculating this propagator is crucial because the dielectric permittivity, \epsilon(\omega), of the QGP is directly related to the polarization tensor, which is derived from the one-loop resummed gluon propagator. The dielectric permittivity, in turn, screens the color Coulomb interaction between static quarks, effectively reducing the strength of the interaction within the QGP and influencing the behavior of heavy quarkonia.

Analysis of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) utilizes theoretical calculations, frequently employing Thermal Wilson-Loop Spectral Functions to determine the real and imaginary components of the interaction potential between quarks. These calculations reveal that the imaginary part of this interaction is inversely proportional to the momentum transfer, q, specifically exhibiting a relationship of \pi/2q. This inverse proportionality indicates a significant dependence of the interaction strength on the spatial separation between the interacting quarks, as higher momentum transfer corresponds to shorter distances and, therefore, a weaker imaginary potential contribution. The extracted real part of the potential, alongside the imaginary component, provides a complete description of the screened interaction within the QGP.

The Generalized Gauss Law offers a calculational framework for determining the potential energy between static color sources embedded within the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP). This approach extends traditional Gauss’s Law to incorporate the non-perturbative effects present in strongly coupled gauge theories. Analysis using this framework reveals that the contribution to the potential arising from the magnetic component of the QGP scales quadratically with both the quark’s charge (q_f) and the magnetic field strength (B). This quadratic dependence is mathematically expressed as a term proportional to (q_f B)^2, indicating a significant enhancement of the potential with increasing charge or magnetic field intensity.

Challenges Remain: The Quest Continues

Lattice Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), a cornerstone of investigating the quark-gluon plasma (QGP), faces a significant hurdle when simulating conditions involving non-zero chemical potential – a measure of baryon density. This obstacle, known as the ‘sign problem’, arises because the mathematical functions used in Lattice QCD calculations oscillate between positive and negative values, leading to an exponential increase in statistical noise and rendering standard Monte Carlo methods unusable. Consequently, accessing the QGP’s behavior at the extreme temperatures and densities achieved in heavy-ion collisions – crucial for understanding its phase diagram and properties – becomes computationally intractable. The sign problem effectively limits the ability to predict how the QGP evolves under conditions far from equilibrium and restricts detailed investigations into phenomena such as the critical point, where a transition between hadronic matter and the QGP is predicted to occur, thus demanding innovative theoretical and computational approaches to overcome this limitation.

Calculations within Lattice Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), while powerful, face significant hurdles when attempting to model the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) due to non-perturbative effects. These effects, arising from the strong force’s complex interactions, aren’t easily addressed by standard perturbative techniques, demanding more sophisticated approaches. Specifically, dimension-two gluon condensates – quantum fluctuations in the gluon field – contribute significantly to the overall energy density and alter the behavior of quarks and gluons within the QGP. Their influence isn’t simply a minor correction; instead, they fundamentally reshape the theoretical landscape, requiring careful inclusion in models to accurately predict experimental observables. Ignoring these condensates leads to discrepancies between theoretical predictions and data obtained from heavy-ion collision experiments, underscoring the necessity for ongoing research into their precise role and effective implementation within Lattice QCD calculations.

The Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR) represents a significant leap forward in the study of strongly interacting matter. This next-generation facility, currently under construction in Darmstadt, Germany, is designed to deliver unprecedented ion beam intensities and energies, opening up entirely new energy regimes for probing the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). Specifically, FAIR will enable detailed investigations of heavy quarkonia – bound states of heavy quarks like charm and bottom – under extreme conditions of temperature and density. By accessing previously unreachable energy scales, researchers anticipate gaining crucial insights into the dissociation and recombination mechanisms of these particles within the QGP, and how these processes contribute to the overall thermalization and evolution of the plasma created in heavy-ion collisions. This expanded experimental reach promises to resolve long-standing questions about deconfinement and the nature of the strong force, providing stringent tests of both perturbative and non-perturbative quantum chromodynamics.

Theoretical investigations increasingly turn to alternative frameworks like the AdS/CFT correspondence to unravel the complexities of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) and its influence on heavy quarkonia. This approach, rooted in string theory, offers a potentially powerful method for modeling strongly coupled systems where traditional perturbative techniques falter. Recent studies focusing on thermal width – a measure of how quickly quarkonia are suppressed at high temperatures – reveal that the J/ψ meson exhibits the largest thermal width among those investigated. This finding suggests that the J/ψ experiences the most substantial suppression due to thermal broadening within the QGP, implying it serves as a particularly sensitive probe of the plasma’s extreme conditions and necessitating refined theoretical models to accurately capture its behavior.

The pursuit of understanding quarkonium dissociation within the quark-gluon plasma feels…predictable. This paper diligently maps the influence of chemical potential and magnetic fields, finding them secondary to temperature. It’s a refinement, certainly, but hardly a revolution. One suspects the authors will revisit these findings when production data inevitably introduces unforeseen complexities. As Niels Bohr observed, “Predictions are difficult, especially about the future.” It’s a sentiment acutely applicable here; the elegant theoretical framework will, with time, reveal itself as just another layer of tech debt, awaiting the inevitable breakage that real-world conditions impose. The study meticulously charts the thermal width, but the universe, predictably, will find a way to widen it further.

The Road Ahead

The persistent focus on quarkonium dissociation, even with the added dimensions of chemical potential and weak magnetic fields, feels less like charting new territory and more like refining the map of a well-trodden landscape. The study confirms temperature remains the primary architect of these systems’ demise – a predictable outcome, perhaps, yet one stubbornly resistant to complete theoretical capture. Every parameter optimized for dissociation will, inevitably, be optimized back, as the production environment discovers novel routes to survival.

The subtle corrections introduced by chemical potential and magnetic fields are valuable, certainly, but point to a larger, less glamorous truth: architecture isn’t a diagram, it’s a compromise that survived deployment. The field seems destined to cycle between increasingly complex models and the sobering realization that lattice QCD, while powerful, still operates with approximations. A true understanding demands reconciling these simulations with experimental data – a task perpetually hampered by the inherent challenges of recreating, and interpreting, the conditions of the early universe.

The next iteration won’t be about discovering new physics, but about better accounting for the messy, incomplete physics already known. It’s not about building more elegant theories; it’s about resuscitating hope in the face of irreducible complexity. The focus will shift, not to what could dissociate quarkonium, but to what actually keeps it together, however briefly, in a universe determined to pull it apart.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10634.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Yakuza Kiwami 3 And Dark Ties Guide – How To Farm Training Points

- How to Build a Waterfall in Enshrouded

- Meet the cast of Mighty Nein: Every Critical Role character explained

- These Are the 10 Best Stephen King Movies of All Time

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

2026-01-18 23:57