Author: Denis Avetisyan

A novel framework leveraging generative models is reshaping how we tackle ill-posed problems in fields ranging from imaging to particle physics.

This review details the Ensemble Inverse Generative Models approach, focusing on posterior sampling techniques like diffusion models and flow matching for enhanced performance in inverse problem solving.

Reconstructing true distributions from distorted observations is a fundamental challenge across diverse fields, often complicated by ill-posed inverse problems and unknown prior distributions. This paper, ‘The Ensemble Inverse Problem: Applications and Methods’, introduces a novel framework for addressing this challenge via Ensemble Inverse Generative Models, which leverage conditional generative models for efficient posterior sampling. By training on ensembles of truth-observation pairs, the method implicitly encodes the likelihood and enables generalization to unseen priors, avoiding iterative use of the forward model at inference time. Could this approach unlock more robust and accurate solutions in areas ranging from high-energy physics unfolding to inverse imaging and full waveform inversion?

The Inherent Challenge of Probabilistic Mapping

The pursuit of accurate posterior inference underpins a vast range of scientific endeavors, from cosmological modeling and climate prediction to medical diagnosis and machine learning. However, determining this posterior – the probability distribution of parameters given observed data – often presents a formidable computational challenge. The intractability arises because calculating the posterior typically requires integrating over an extremely high-dimensional space, a process that quickly becomes impossible even with powerful computers. This limitation forces researchers to rely on approximations, such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods or variational inference, which, while offering practical solutions, inevitably introduce biases and uncertainties that can compromise the reliability of subsequent analyses and interpretations. The difficulty isn’t simply a matter of needing more computing power; it’s a fundamental obstacle stemming from the inherent complexity of many real-world probabilistic models.

Conventional Bayesian methods, while theoretically sound, often falter when confronted with the complexities of high-dimensional data. The computational burden of integrating over numerous parameters-a core requirement for obtaining the posterior distribution-grows exponentially with dimensionality, quickly becoming insurmountable. To address this, researchers frequently resort to simplifying assumptions, such as assuming parameter independence or employing variational approximations. However, these approximations inevitably introduce biases and inaccuracies, potentially leading to flawed inferences and misleading conclusions. The trade-off between computational feasibility and statistical accuracy represents a significant challenge in modern data analysis, driving the development of more sophisticated inference techniques capable of handling complex, high-dimensional models without sacrificing precision.

Generative Pathways to Posterior Recovery

The Evidence of Information Processing – Stage II (EIP-II) problem, concerning intractable posterior distributions in Bayesian inference, can be addressed through generative modeling by directly learning the data distribution p(x). Instead of explicitly calculating the posterior p(z|x), generative models aim to approximate this distribution by learning to generate data samples similar to those observed. This is achieved by training a model to estimate the probability density of the data, effectively learning the underlying structure and dependencies within the dataset. Successful approximation allows for posterior inference through sampling methods, circumventing the need for complex and computationally expensive analytical solutions or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques. The efficacy of this approach depends on the model’s capacity to accurately represent the data distribution and generate realistic samples.

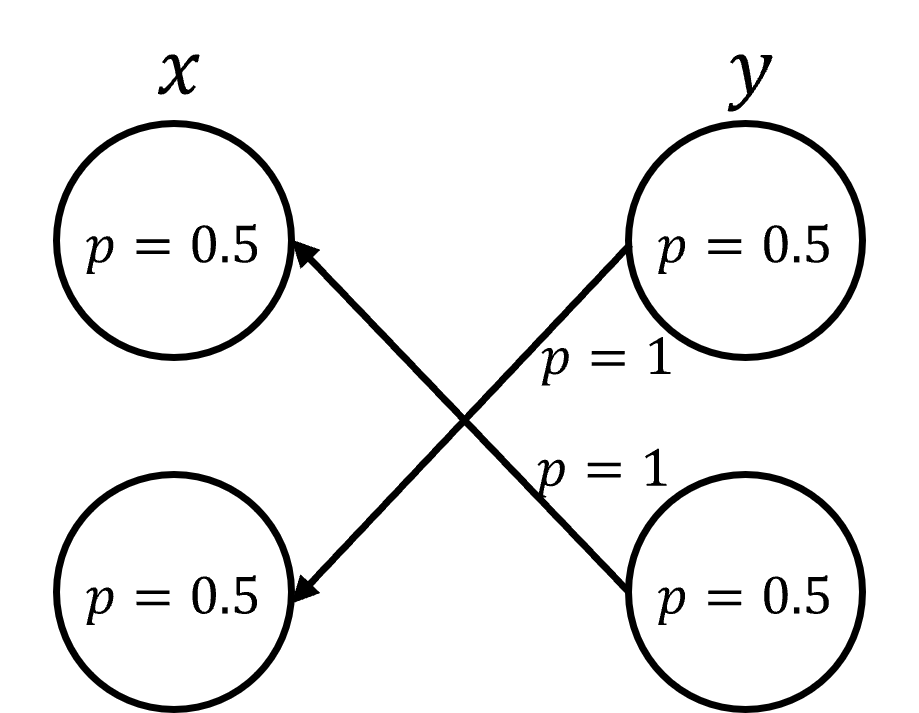

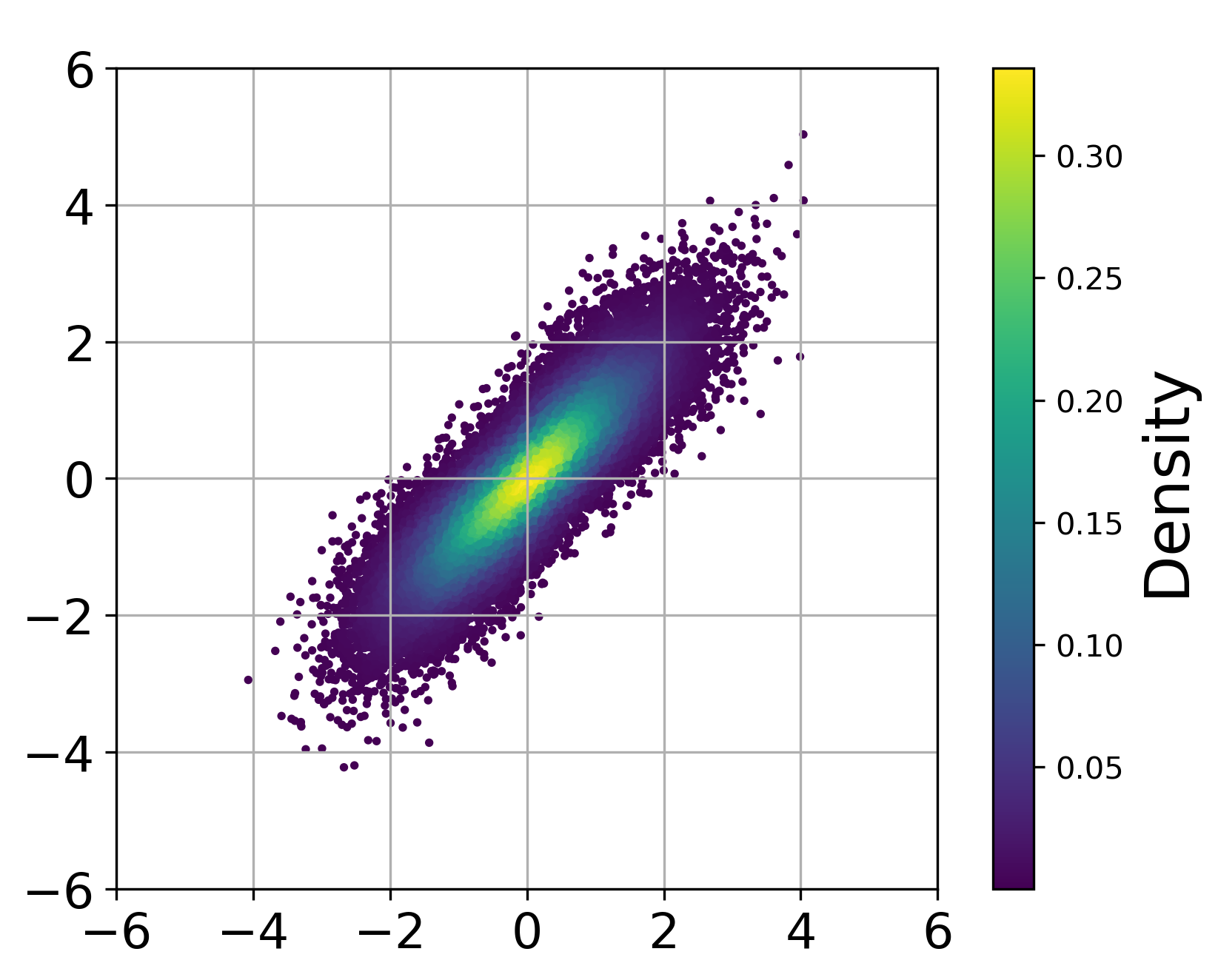

Conditional generative models, including diffusion and flow matching techniques, demonstrate superior performance in sampling from high-dimensional and complex probability distributions. Diffusion models achieve this through a process of progressively adding noise to data until it resembles a simple distribution, then learning to reverse this process to generate new samples. Flow matching, conversely, learns a continuous normalizing flow that directly maps data to a simple distribution, enabling efficient sampling via a deterministic change of variables. Both approaches surpass traditional methods, such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), in generating high-fidelity samples and accurately representing intricate data distributions, particularly when dealing with conditional generation tasks where samples must adhere to specific constraints or conditions. P(x|c) represents the conditional probability of generating a sample x given a condition c.

Generative models address the challenge of posterior inference by directly learning to represent the posterior distribution p(x|y) , where x represents the latent variable and y the observed data. Rather than relying on traditional methods like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) or variational inference, which require computationally expensive direct calculations of the posterior, these models learn a parameterized distribution that approximates the true posterior. Sampling from this learned distribution then provides representative samples from the posterior, enabling downstream tasks without explicitly computing the intractable normalizing constant or performing iterative approximation schemes. This approach is particularly beneficial in high-dimensional spaces or with complex models where direct computation is infeasible.

Ensemble Insights: Refining the Probabilistic Landscape

Ensemble information, derived from analyzing multiple observations of a phenomenon, enhances posterior inference by providing a more comprehensive dataset for probabilistic modeling. Traditional inference methods often rely on single observations, which can be susceptible to noise and limited in their ability to capture the full range of possible outcomes. By incorporating data from multiple sources, ensemble techniques effectively reduce uncertainty and improve the precision of estimated posterior distributions. This is achieved by aggregating information across observations, allowing the model to better constrain the parameter space and arrive at more reliable conclusions regarding the underlying probability distribution. The benefits are particularly pronounced in scenarios with high dimensionality or complex relationships, where a single observation may not be sufficient to accurately characterize the system.

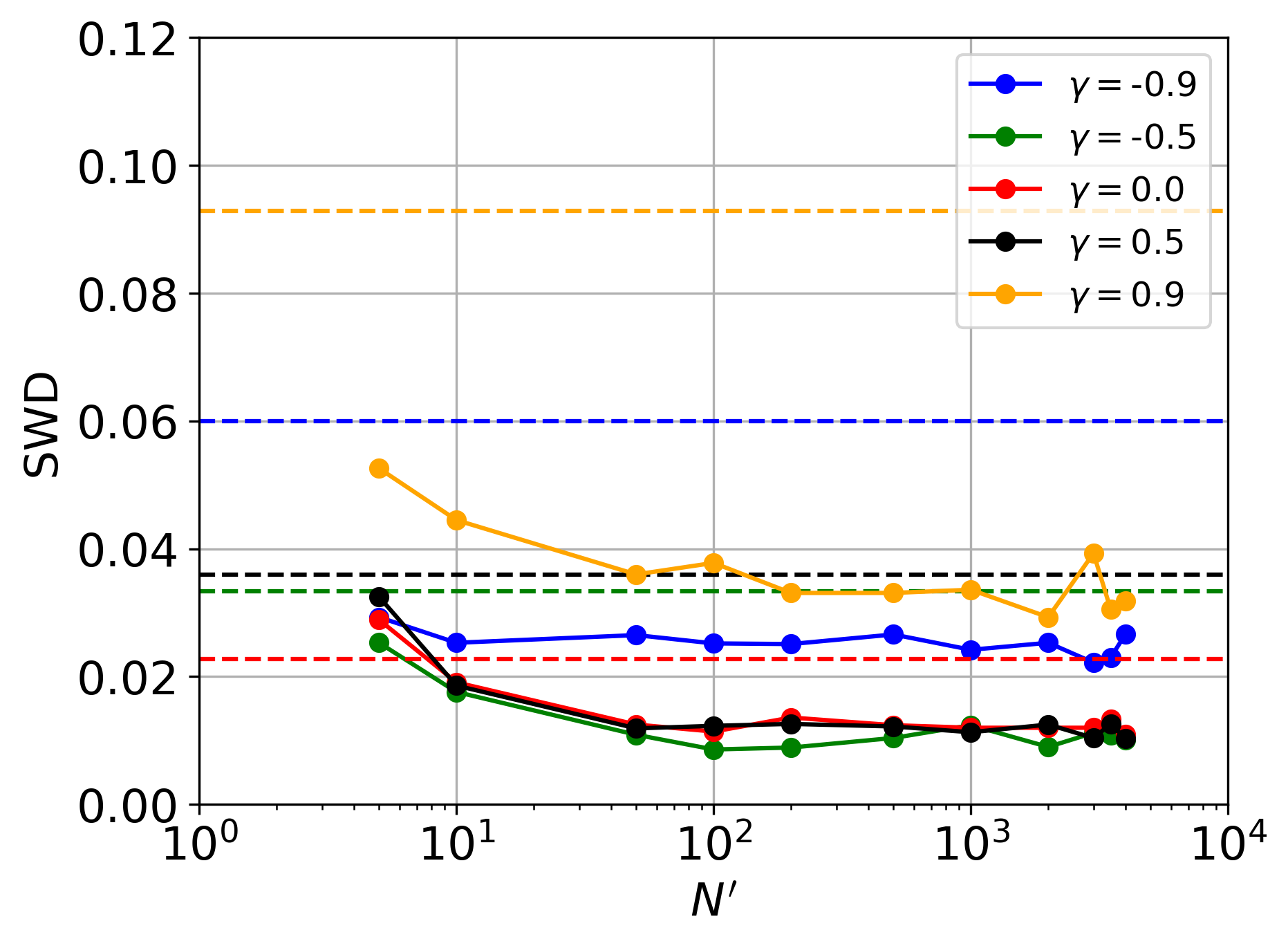

EI-DDPM and EI-FM represent extensions to established generative modeling techniques – Diffusion and Flow Matching, respectively – achieved through the incorporation of ensemble information as a conditioning variable. Standard diffusion and flow matching models are modified to accept, as input, features derived from multiple observations rather than a single data point. This conditioning allows the models to leverage the collective knowledge contained within the ensemble, influencing the generative process and ultimately refining the posterior inference. Specifically, the models learn to map from the ensemble features to the target distribution, effectively utilizing the additional information to improve their predictive capabilities and reduce uncertainty in the generated samples.

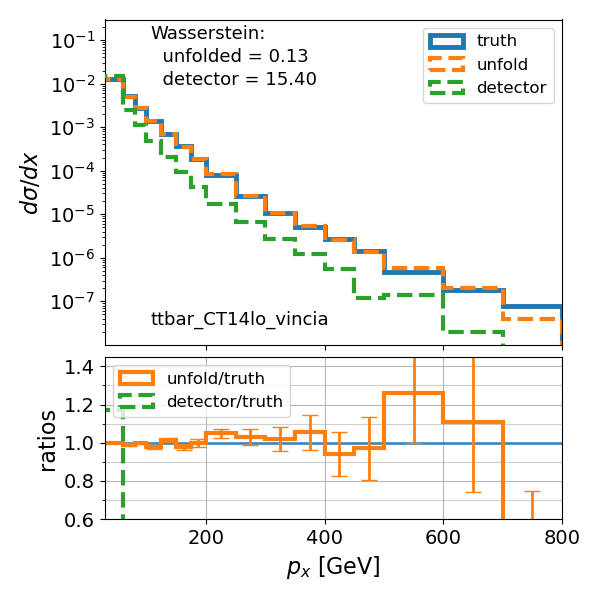

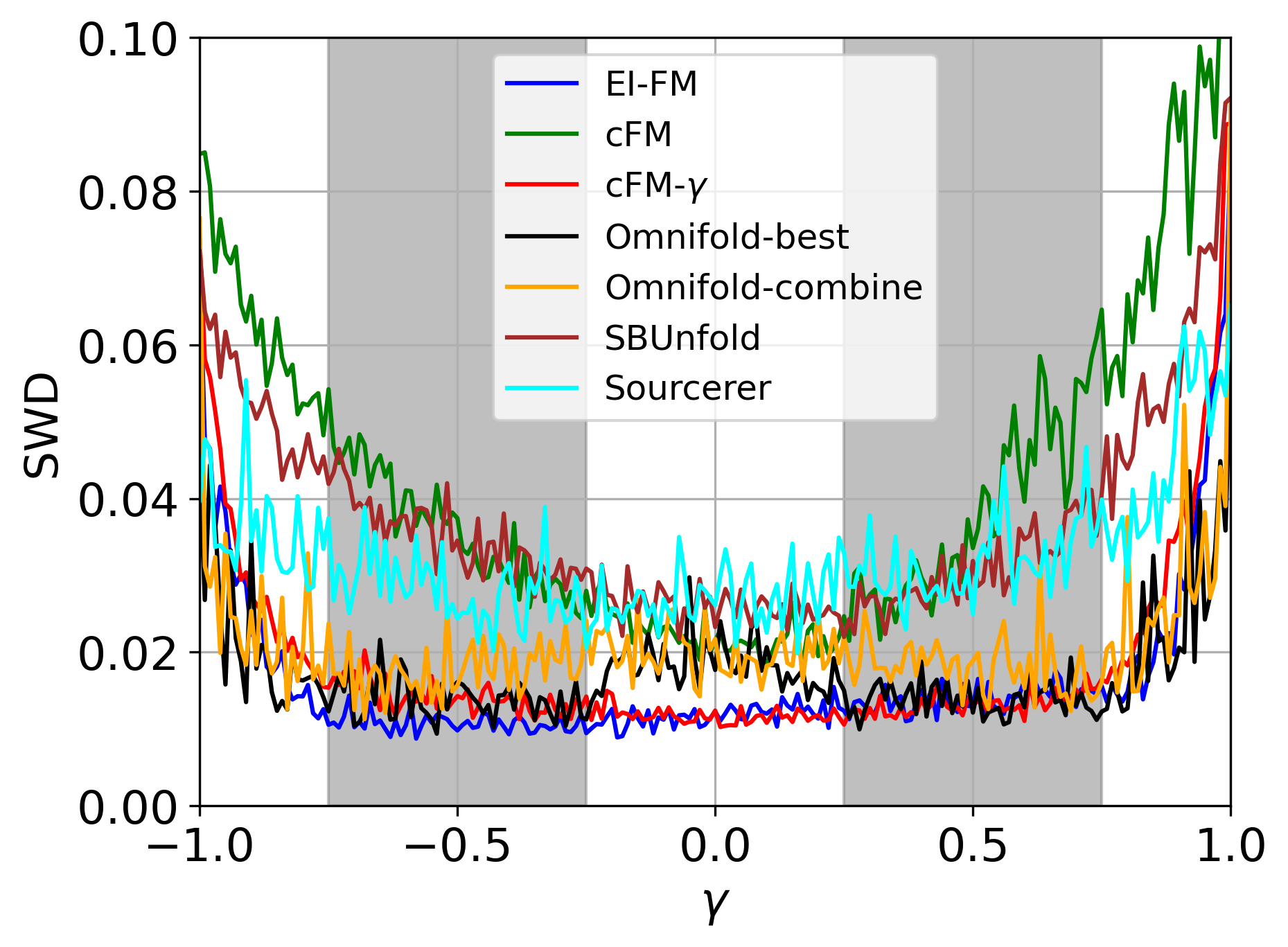

Evaluations of EI-DDPM and EI-FM models on particle physics data unfolding tasks consistently report lower Wasserstein distance values compared to standard diffusion and flow matching techniques, as well as other established unfolding methods. The Wasserstein distance, a metric for comparing probability distributions, directly quantifies the discrepancy between the unfolded particle distribution and the true underlying distribution. Lower Wasserstein distance values indicate a closer approximation to the true distribution, and therefore, improved accuracy in the unfolding process. This performance advantage has been observed across multiple datasets and parameter configurations, establishing the efficacy of incorporating ensemble information for enhanced unfolding results.

Permutation invariant neural networks (PINNs) are crucial for processing ensemble information as they are designed to yield consistent outputs regardless of the order of input observations within a set. This property is essential because the order of observations in an ensemble typically carries no inherent physical meaning; the underlying physical process remains unchanged by reordering the input data. PINNs achieve this invariance through the use of symmetric functions – such as sums or means – applied to the input features, ensuring the network focuses on the collective properties of the ensemble rather than their specific arrangement. This allows the model to generalize effectively across different permutations of the same underlying data, which is vital for accurate posterior inference when leveraging ensemble information in applications like particle physics unfolding.

Validating the Map: Assessing Posterior Fidelity

The reliability of any statistical inference hinges on the accuracy of the estimated posterior distributions; a poorly characterized posterior can lead to misleading conclusions and flawed decision-making. Consequently, rigorous assessment of posterior quality is paramount. Researchers employ metrics like Total Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve for Probabilistic Coverage (TARP Coverage) to quantify how well the estimated posterior encapsulates the true parameter value. TARP Coverage essentially measures the probability that a credible interval – derived from the posterior – contains the actual value of interest, providing a direct indication of the posterior’s calibration. A posterior with high TARP Coverage is considered well-calibrated, meaning its credible intervals accurately reflect the uncertainty surrounding the estimate. Therefore, maximizing TARP Coverage serves as a key objective in developing and validating sophisticated inference frameworks.

The reliability of any statistical inference hinges on the accuracy of the resulting posterior distributions; therefore, a robust evaluation of these distributions is paramount. Recent advancements in this framework demonstrate a notably reduced deviation from ideal Total Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (TARP) coverage when compared to conventional methodologies. This improved alignment with ideal TARP coverage signifies a heightened degree of posterior accuracy, suggesting the framework more effectively captures the true uncertainty associated with estimated parameters. Essentially, the results indicate a lower probability of drawing incorrect conclusions due to inaccuracies in the posterior representation, thereby bolstering the confidence in the inferences derived from this approach.

Prior to statistical inference, data frequently undergoes a process called unfolding, a technique designed to mitigate the distorting influence of detection apparatus. This preparatory step effectively reverses the effects introduced by the detector, revealing a more accurate representation of the underlying phenomenon being studied. By removing these detector-induced biases, unfolding allows for a more faithful reconstruction of the true signal, ultimately enhancing the performance and reliability of subsequent modeling efforts. The approach is crucial in fields where precise measurements are paramount, ensuring that inferences are based on the actual characteristics of the system rather than artifacts of the measurement process itself.

Quantifying the difference between an estimated probability distribution and the true, but often unknown, distribution is a central challenge in Bayesian inference. This research leverages the Wasserstein distance – also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance – as a robust metric for precisely this purpose; it measures the minimum ‘work’ required to transform one distribution into another, offering a more intuitive and sensitive comparison than traditional metrics like Kullback-Leibler divergence. Consistently achieving lower Wasserstein distances between estimated and true posterior distributions demonstrates a significant advancement in the accuracy of the proposed framework. These lower values indicate that the estimated distributions are, on average, closer to the true underlying distributions, bolstering confidence in the reliability of subsequent inferences and predictive modeling, particularly in complex inverse problems where characterizing posterior uncertainty is paramount.

Evaluations revealed significant gains in image quality and geophysical model fidelity through the implemented techniques. Specifically, the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) demonstrated improvements, indicating enhanced perceptual similarity between reconstructed images and ground truth data. Simultaneously, reductions in Mean Squared Error (MSE) confirmed a decrease in the average squared difference between estimated and actual values, suggesting a more accurate representation of the underlying signal. These improvements were consistently observed in both image reconstruction tasks and Full Waveform Inversion (FWI), surpassing the performance of established baseline methods and highlighting the framework’s capacity to generate higher-resolution, more faithful results.

The pursuit of solutions to the Ensemble Inverse Problem, as detailed in this work, inherently acknowledges the transient nature of any modeled system. The framework of Ensemble Inverse Generative Models, with its reliance on posterior sampling via diffusion or flow matching, doesn’t offer a static ‘solution’ but rather a continually refined approximation. As Edsger W. Dijkstra observed, “It’s not enough to have good code; you have to have good documentation.” This sentiment resonates deeply – the generative models themselves represent a form of documentation of the underlying data distribution, and their effectiveness is inextricably linked to how accurately that distribution is captured and maintained. Any simplification in the modeling process, while expedient, carries a future cost in terms of representational fidelity, much like accumulating technical debt within a system’s memory.

What Lies Ahead?

The presented work, while demonstrating a functional approach to the Ensemble Inverse Problem, inevitably highlights the inherent limitations of any system attempting to reconstruct a past state. Versioning, in the context of generative models, becomes a form of memory-a curated lineage of approximations. Each iteration refines the reconstruction, yet simultaneously distances it further from the originating reality. The true signal, after all, is forever lost in the unfolding of time.

Future explorations will likely focus on the meta-problem: how to quantify and manage the accumulated drift inherent in these iterative processes. The arrow of time always points toward refactoring- toward acknowledging the inevitable degradation of information. Current generative models excel at creating plausible outputs, but struggle with guarantees of fidelity, especially when extrapolating beyond the training data’s limited scope.

The eventual horizon is not perfect reconstruction, but rather the development of robust methods for calibrating uncertainty. Acknowledging the inherent imperfections of the inverse problem, and designing systems that gracefully accommodate them, represents a more sustainable path than pursuing increasingly complex attempts at absolute retrieval. The emphasis will shift from solving the problem to living with its limitations.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.22029.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- Battlefield 6 Season 2 Update Is Live, Here Are the Full Patch Notes

- Dan Da Dan Chapter 226 Release Date & Where to Read

- ‘Crime 101’ Ending, Explained

- Ashes of Creation Mage Guide for Beginners

- Duffer Brothers Discuss ‘Stranger Things’ Season 1 Vecna Theory

- Winx Club: The Magic is Back announced for PS5, Switch, and PC

2026-02-02 00:43