Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new spectroscopic technique using precisely controlled Rydberg atoms allows researchers to map out the energy landscape of complex magnetic materials.

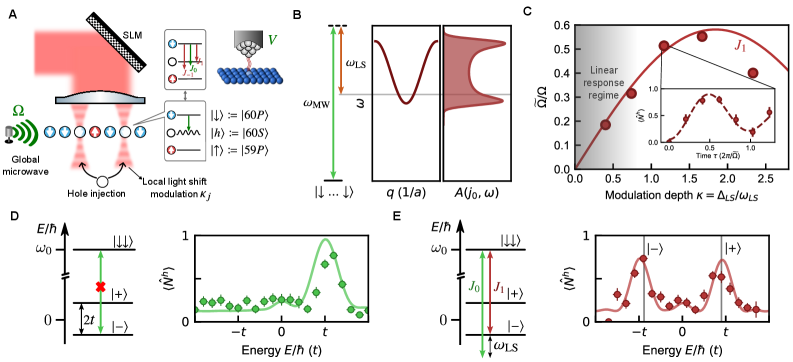

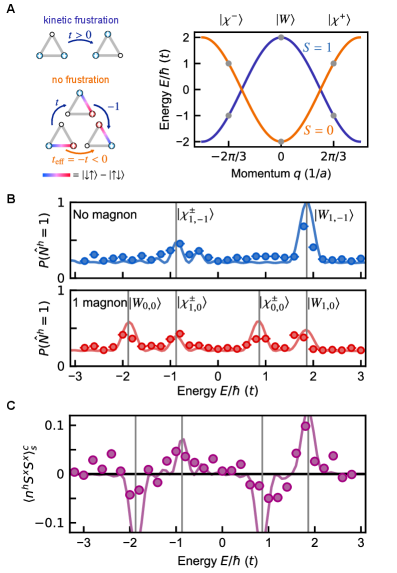

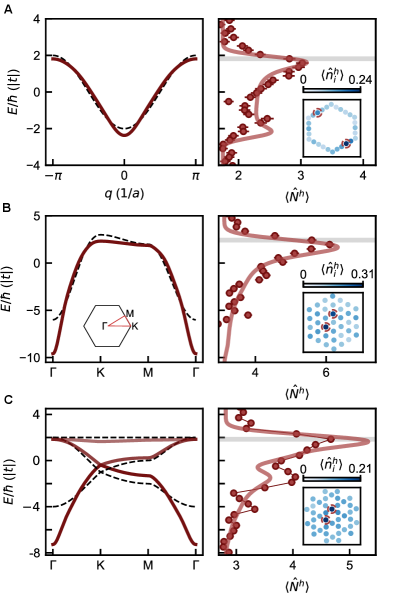

This work demonstrates the measurement of local density of states and single-particle excitations in correlated quantum systems using light-shift modulated Rydberg tweezer arrays on a triangular lattice.

Understanding the emergent behavior of strongly correlated quantum materials requires resolving the energy and spatial structure of their elementary excitations, a challenge often limited by conventional spectroscopic techniques. Here, in ‘Measuring spectral functions of doped magnets with Rydberg tweezer arrays’, we demonstrate a novel spectroscopic protocol utilizing spatially resolved Rydberg atom arrays to directly measure single-particle spectral functions and image the underlying microscopic structure of excitations in frustrated systems. This approach reveals key properties of magnetic polarons – bound states of holes and magnons – including their binding energy, spatial extent, and spin character, while also enabling measurements of the local density of states across different lattice geometries. Does this platform offer a pathway toward a comprehensive understanding of exotic quantum phases and the design of novel quantum materials?

Unveiling the Limits of Conventional Quantum Models

The behavior of many-body quantum systems, prevalent in advanced materials, often diverges from predictions based on independent particle models due to the strong correlations arising from interactions between constituent particles. Unlike systems where each particle’s behavior is largely unaffected by others, these materials exhibit collective phenomena where electron-electron, or spin-spin interactions fundamentally alter the system’s properties. This interconnectedness means that a simple, additive understanding – where the whole is the sum of its parts – breaks down; instead, emergent behaviors arise that are not predictable from individual particle characteristics. Consequently, traditional approximations, which rely on treating particles as independent entities, frequently fail to accurately capture the system’s ground state or excited state properties, necessitating the development of sophisticated theoretical and computational methods to address these complex quantum correlations.

The predictive power of many established computational techniques diminishes when applied to systems exhibiting kinetic frustration, a phenomenon arising from competing interactions that prevent a simple, ground state ordering. These methods, often reliant on approximations of individual particle behavior, fail to capture the collective effects where particles ‘want’ to occupy multiple, conflicting positions simultaneously. This leads to a ‘frozen’ or disordered state, not due to thermal fluctuations, but because the system fundamentally cannot minimize its energy across all possible configurations. Consequently, calculations can yield inaccurate predictions for material properties – like magnetism or conductivity – and hinder the rational design of novel materials where these frustrated interactions could unlock extraordinary functionalities. The inability to reliably model these complex interplay necessitates the development of innovative theoretical approaches and computational strategies capable of addressing the inherent many-body correlations at play.

The pursuit of materials exhibiting entirely new behaviors hinges on a deep comprehension of frustrated quantum systems. These materials, where competing interactions prevent a simple, stable ground state, offer a pathway to emergent properties – phenomena not readily predictable from the characteristics of individual components. Researchers believe that carefully engineering frustration can unlock functionalities like high-temperature superconductivity, novel magnetism, or topologically protected quantum computation. Unlike conventional materials where properties are largely determined by composition, frustrated systems allow for manipulation of interactions to ‘program’ desired responses, potentially leading to materials with adaptable and unprecedented capabilities. This field represents a paradigm shift in materials science, moving beyond simply discovering new substances to actively designing materials with tailored, revolutionary properties.

Rydberg Quantum Simulation: A Platform for Atomic Control

Rydberg quantum simulators achieve control over individual atoms by exciting them to highly energetic Rydberg states. These states exhibit exaggerated atomic properties, including large dipole moments and long-range interactions, which are sensitive to external fields. This sensitivity allows for precise manipulation of atomic positions and interactions using focused laser beams, creating customizable arrangements of atoms-referred to as custom quantum systems-with controlled connectivity. The degree of control extends to the ability to program interactions between individual atoms, effectively designing the Hamiltonian of the simulated quantum system and enabling studies of complex quantum phenomena beyond the reach of classical computation.

Optical lattices and Rydberg tweezer arrays are distinct but complementary methods for constructing controllable quantum systems. Optical lattices utilize the interference pattern of laser beams to create periodic potentials that trap neutral atoms at lattice sites, defining the system’s geometry. Rydberg tweezer arrays, conversely, employ tightly focused laser beams – optical tweezers – to individually trap and position atoms, offering greater flexibility in arranging lattice geometries, including non-periodic configurations. Crucially, both platforms allow for precise control over the interactions between atoms by exciting them to highly excited Rydberg states; the strength of these interactions is determined by the distance between atoms and the specific Rydberg state chosen, enabling the realization of diverse interaction strengths and tailored quantum many-body systems.

Manipulation and observation of quantum states in Rydberg atom arrays are achieved through the application of precisely tuned global microwave drives and frequency-resolved injection techniques. Global microwave drives induce coherent transitions between hyperfine energy levels within the Rydberg manifold, allowing for the controlled excitation and manipulation of individual atoms or collective modes. Frequency-resolved injection, utilizing narrow-bandwidth microwave signals, selectively addresses specific atoms based on their transition frequencies, enabling individual addressing and high-fidelity control. This technique also facilitates the measurement of atomic state via absorption or emission of microwave photons, allowing for non-destructive quantum state tomography and real-time monitoring of quantum dynamics. The combination of these techniques allows for the implementation of complex quantum algorithms and the exploration of many-body quantum phenomena.

Probing the Emergence of Hole-Magnon Bound States

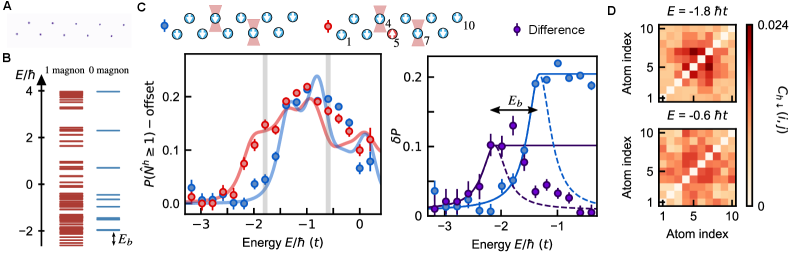

The formation of hole-magnon bound states is predicted within the framework of the t-J model, a simplified representation of strongly correlated electron systems. This model focuses on the behavior of electrons with restricted movement and strong interactions, particularly relevant in materials like high-temperature superconductors. Within this model, a ‘hole’ – representing the absence of an electron – interacts with ‘magnons’, which are quantized collective excitations of the electron spin system. These interactions can lead to the formation of a bound state where the hole and magnon are correlated and move together as a single quasiparticle, distinct from individual electrons or magnons. The t-J model provides a theoretical basis for understanding the emergence of these bound states and their role in the material’s electronic properties.

Hole-magnon bound states originate from the interaction between ‘holes’ – which represent the absence of electrons in the material – and ‘magnons’. Magnons are quantized collective excitations of the electron spin system, behaving as quasiparticles with defined energy and momentum. The interaction between these holes and magnons results in a bound state where the hole effectively dresses itself with surrounding magnons, lowering the overall energy of the system. This binding occurs due to the exchange interaction between the electron spin of the missing electron (hole) and the collective spin excitations (magnons), leading to a stable, composite quasiparticle with a characteristic binding energy.

Characterization of hole-magnon bound states was achieved through a combined methodology of theoretical calculation and experimental measurement. Specifically, theoretical predictions were generated using the Gutzwiller projector, a technique for studying strongly correlated electron systems, and compared with experimentally obtained local density of states (LDOS) data. This approach enabled the observation of these bound states with a binding energy resolution sufficient to confirm their existence and characterize their properties, as detailed in this work. The combination of theoretical modeling and high-resolution experimental data provides strong evidence for the formation and stability of hole-magnon bound states in the studied system.

Measurements conducted on a triangular lattice system have enabled the characterization of hole-magnon bound state binding energies. Analysis of the local density of states (LDOS) revealed distinct spectral features attributable to these bound states, allowing for determination of their binding energies with sufficient resolution to confirm their existence. The observed binding energies are dependent on the specific lattice parameters and doping levels of the triangular lattice material, indicating a strong interplay between the electronic structure and the collective spin excitations. These experimental results provide quantitative data supporting the theoretical predictions derived from the ‘t-J’ model and Gutzwiller projector calculations.

Engineering Quantum Control Through Local Light Shifts

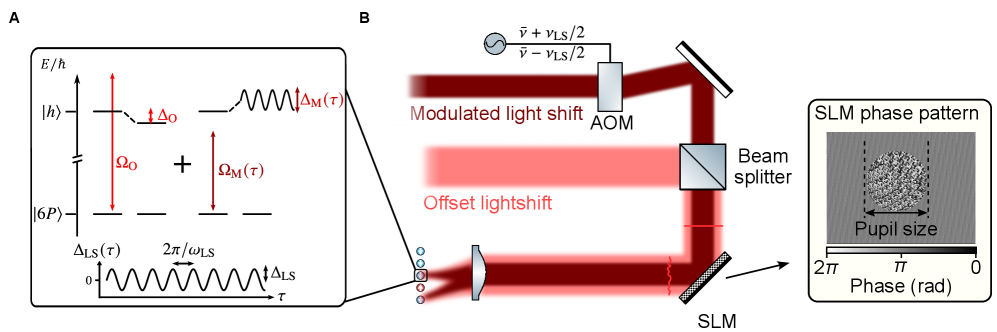

Precisely controlling the interactions between individual atoms is now achievable through a technique called local light-shift modulation. This method leverages the AC Stark shift – a change in an atom’s energy levels caused by an external light field – to subtly reshape the potential landscape experienced by the atoms. By carefully tuning the intensity and frequency of these localized light fields, researchers can effectively dial in the strength and nature of atomic interactions, effectively customizing the system’s collective behavior. This granular control allows for the creation of designer materials with pre-determined properties, opening doors to explore novel quantum phenomena and potentially leading to advancements in areas like quantum simulation and information processing. The ability to engineer interactions at this level represents a significant leap forward in manipulating matter at the atomic scale.

The application of modulated light fields induces an ‘AC Stark shift’, fundamentally altering the potential energy landscape experienced by atoms within the system. This shift isn’t merely a static displacement; rather, it represents a tunable modification of the atomic energy levels, effectively reshaping the ‘hills and valleys’ that dictate atomic behavior. By precisely controlling the frequency and intensity of these light fields, researchers can sculpt the potential to favor specific atomic configurations or pathways. This dynamic control allows for the creation of customized potentials, enabling the investigation of phenomena typically requiring strong interactions or extreme conditions. Consequently, the AC Stark shift serves as a versatile tool for manipulating atomic motion and exploring novel quantum states, offering a pathway towards engineering matter with unprecedented precision and control- \Delta E \propto \Omega^2 -where Ω represents the Rabi frequency of the applied light.

Recent investigations have revealed a precise method for manipulating atomic interactions through light modulation, demonstrating that the hopping amplitude – a measure of particle movement between lattice sites – can be effectively renormalized. This renormalization follows the relationship t \sim = t J_0(\kappa), where J_0 is a Bessel function of the first kind and κ represents the modulation depth. Simultaneously, the effective local Rabi frequency, which dictates the strength of light-atom coupling, experiences enhancement due to sideband coupling, scaling as \Omega \sim = \Omega J_1(\kappa), with J_1 being another Bessel function. These findings establish a pathway to finely tune quantum systems; by controlling κ, the system’s energy landscape and dynamics can be precisely engineered, offering unprecedented control over atomic behavior and opening avenues for exploring complex quantum phenomena.

By precisely modulating the interactions between atoms with light, researchers are able to engineer artificial gauge fields – effectively recreating the magnetic forces experienced by electrons in solid materials, but within a completely controllable quantum system. This ability unlocks the potential to explore exotic states of matter known as topological phases, characterized by robust edge states and immunity to disorder. These artificially created topological systems offer a unique platform for studying fundamental physics and could pave the way for novel quantum technologies, as the robust nature of topological states promises enhanced resilience against environmental noise – a significant hurdle in building practical quantum devices. The manipulation of these systems allows for the simulation of complex physical phenomena and the potential design of materials with tailored electronic properties.

The pursuit of understanding correlated quantum states, as demonstrated in this work utilizing Rydberg tweezer arrays, necessitates a holistic view of system behavior. Just as a complex organism’s health depends on the interplay of its parts, so too does the stability of these quantum systems hinge on recognizing the connections between individual elements. Richard Feynman observed, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.” This sentiment resonates deeply with the approach presented, where precise spectroscopic measurements-probing single-particle excitations and the local density of states-demand rigorous self-consistency and an avoidance of superficial interpretations. The technique offers a path to anticipate potential weaknesses within the quantum lattice, revealing how structure dictates behavior and ultimately, system stability.

Where the Field Now Turns

The capacity to resolve local spectral functions, as demonstrated, is not merely a refinement of spectroscopic technique. It is an acknowledgement that understanding complex quantum systems requires dissecting the emergent properties arising from the interplay of constituent parts. The current work, while elegant in its implementation, highlights a persistent challenge: the scalability of maintaining coherent control over increasingly complex lattices. The true test will not be achieving larger arrays, but in establishing a clear, predictable relationship between system architecture and the resulting quantum behavior.

One anticipates a natural progression towards probing genuinely collective phenomena. The triangular lattice, while offering interesting theoretical possibilities, is but one instantiation. Future investigations must consider geometries explicitly designed to frustrate certain interactions, forcing the system to explore novel ground states. The ecosystem of control-light-shift modulation, atom addressing, and measurement fidelity-must evolve in tandem with the lattice itself. Simply put, increasing the number of atoms without increasing the clarity of the signal is a diminishing return.

Ultimately, the value lies not in simulating known physics with increasing precision, but in using these platforms to discover the unexpected. The capacity to resolve local density of states provides a lens through which to observe the subtle fingerprints of emergent order. The next phase will demand a shift in focus: from asking ‘can it be done?’ to ‘what does it mean?’.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17600.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Battlefield 6 Season 2 Update Is Live, Here Are the Full Patch Notes

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- ‘Crime 101’ Ending, Explained

- Ashes of Creation Mage Guide for Beginners

- Dan Da Dan Chapter 226 Release Date & Where to Read

- Duffer Brothers Discuss ‘Stranger Things’ Season 1 Vecna Theory

- Tom Hanks Called The Best Years of Our Lives ‘the Best Film About WW2’

2026-02-22 13:59