Author: Denis Avetisyan

The ALPS II collaboration details the rigorous calibration and uncertainty analysis underpinning its search for new physics beyond the Standard Model.

This paper presents the calibration procedure and associated systematic uncertainties for the ALPS II experiment’s light-shining-through-a-wall search.

Despite the success of the Standard Model, fundamental questions regarding dark matter and other phenomena suggest the existence of physics beyond our current understanding. The paper ‘Any Light Particle Searches with ALPS II: first science campaign’ details the initial results from a search for beyond the Standard Model (BSM) particles-specifically, pseudo-Goldstone bosons-using the light-shining-through-a-wall technique with a 100-meter scale experimental apparatus. No evidence for such bosons was found in this first science campaign, achieving photon-boson conversion probability sensitivities of a few 10^{-{13}}. With an ongoing upgrade aiming to enhance sensitivity by four orders of magnitude, can ALPS II unlock new insights into the hidden sectors of particle physics?

The Universe’s Hidden Signals: Why We Search Beyond What We Know

Despite its remarkable predictive power, the Standard Model of particle physics remains incomplete, leaving fundamental questions unanswered about the universe. Phenomena like dark matter, dark energy, and the observed matter-antimatter asymmetry suggest the existence of particles and interactions beyond those currently described. The model doesn’t account for gravity, nor does it explain the masses of neutrinos, prompting physicists to theorize about a ‘beyond the Standard Model’ (BSM) physics. These theoretical extensions propose new particles – such as supersymmetry partners, extra dimensions, or sterile neutrinos – that could resolve these inconsistencies and provide a more complete picture of reality. The search for these elusive particles represents a central challenge in modern physics, driving the development of increasingly sophisticated experiments and analysis techniques at facilities around the globe.

The search for physics beyond the Standard Model prominently features the axion, a compelling hypothetical particle initially proposed to elegantly resolve the “strong CP problem” within the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). This problem concerns the unexpectedly small value of the neutron electric dipole moment, which QCD doesn’t naturally explain; the axion’s existence would introduce a new symmetry dynamically cancelling the problematic term. Crucially, axions are predicted to interact extremely weakly with ordinary matter, making direct detection exceptionally challenging. Theoretical models suggest a wide range of possible axion masses, driving a diverse array of experimental approaches-from resonant cavities seeking faint microwave signals to searches for the axion’s potential conversion into photons in strong magnetic fields-all striving to unveil this elusive particle and deepen understanding of the fundamental forces governing the universe.

The pursuit of weakly interacting particles demands experimental ingenuity due to the incredibly faint signals they produce. Unlike the readily detectable products of high-energy collisions at facilities like the Large Hadron Collider, these elusive particles often pass through matter virtually undisturbed, necessitating detectors with extreme sensitivity and innovative designs. Researchers employ a range of strategies, including utilizing powerful magnetic fields to induce subtle interactions, leveraging cryogenic environments to minimize background noise, and developing highly sensitive resonant cavities to amplify potential signals. These experiments frequently require shielding from cosmic rays and other sources of interference, as even the slightest disturbance can obscure the sought-after evidence. The challenge isn’t simply finding these particles, but discerning their presence from the pervasive ‘noise’ of the universe – a feat requiring both technological advancement and a profound understanding of potential confounding factors.

Shining a Light Through the Void: The ALPS II Approach

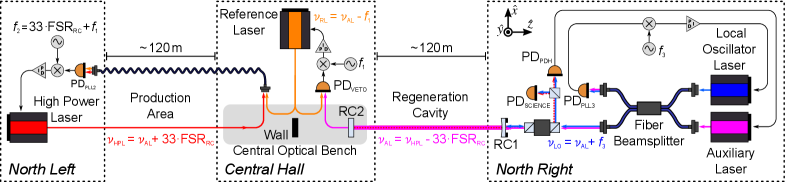

The ALPS II experiment utilizes a ‘light shining through a wall’ approach to search for axions, hypothetical particles proposed as potential dark matter candidates. This technique involves sending a highly polarized laser beam through a strong magnetic field – the ‘wall’ – where photons may convert into axions. If axions are produced, they can traverse the magnetic field region and subsequently reconvert back into photons on the other side, creating a detectable, albeit extremely weak, signal. The experiment is designed to maximize the probability of this photon-axion conversion and subsequent detection, relying on a high-finesse optical cavity to enhance the interaction volume and signal strength. The expected signal rate is exceptionally low, necessitating a highly sensitive detection system and meticulous control over systematic errors.

Optical cavities within the ALPS II experiment function as resonant structures designed to significantly increase the effective path length of photons traversing the magnetic field. These cavities, formed by highly reflective mirrors, allow photons to bounce back and forth multiple times, constructively interfering and amplifying the electromagnetic field. The resonant condition is achieved when the cavity length is an integer multiple of half the photon wavelength, maximizing the probability of photon-axion conversion. This amplification effect dramatically increases the interaction volume, effectively extending the region where conversion can occur without physically increasing the size of the experiment, and thus improving the sensitivity to extremely weak signals.

Precise control of experimental parameters in ALPS II is essential due to the extremely weak signal expected from potential axion-photon conversion. Laser frequency stabilization is a critical technique employed to maintain coherence and maximize signal accumulation. Fluctuations in laser frequency broaden the resonance within the optical cavity, reducing the efficiency of signal amplification and introducing noise. Active feedback loops, utilizing techniques such as Pound-Drever-Hall locking, are implemented to continuously monitor and correct for frequency drift, typically achieving stability on the order of \frac{Hz}{10} . This ensures the laser remains precisely tuned to the cavity resonance over extended data acquisition periods, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio and sensitivity of the experiment.

From Noise to Knowledge: Processing the Signals

Raw data acquired by the ALPS II instrument requires substantial processing to differentiate meaningful signals from background noise and spurious artifacts. This processing centers on data filtering techniques, which are implemented to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). These filters operate by attenuating or removing frequencies and data points identified as contributing primarily to noise, while preserving those indicative of the desired signal. Specific filter parameters and algorithms are selected based on the characteristics of both the expected signal and the dominant noise sources present in the ALPS II data stream. The effectiveness of these filtering procedures is crucial for reliable data analysis and accurate determination of experimental results.

Meticulous data calibration and normalization procedures are essential components of the ALPS II data processing pipeline, designed to correct for systematic errors introduced by instrumental variations and biases. These procedures involve applying correction factors to the raw data to account for detector response non-uniformity, dark current, and other instrumental artifacts. Normalization ensures that data acquired under different experimental conditions are comparable, effectively removing offsets and scaling variations. This process relies on frequent calibrations using established standard sources and careful monitoring of instrumental performance to maintain data integrity and ensure the accuracy of subsequent analyses. The achieved precision, with uncertainty due to open shutter data changes determined to be 7.8% for the S⟂ run, demonstrates the effectiveness of these procedures.

Systematic error mitigation is a critical component of the ALPS II data analysis pipeline, addressing imperfections in the experimental setup and procedure. Following calibration procedures, uncertainty stemming from variations in open shutter data was quantified for the S_{\perp} run, achieving a precision of 7.8%. This level of uncertainty assessment allows for accurate propagation of errors throughout subsequent data analysis and ensures the reliability of the final results by explicitly defining the bounds of experimental imprecision. Further analysis focuses on identifying and minimizing contributions to systematic errors beyond those already addressed through calibration.

Pushing the Boundaries: The Future of the Search

The experimental search for dark matter and other weakly interacting particles often employs the ‘light shining through a wall’ technique, predicated on the quantum mechanical possibility of photons converting into hypothetical particles – known as bosons in this context – within a strong magnetic field. This conversion probability, and thus the likelihood of detecting these elusive particles, is directly proportional to the field’s strength. By implementing significantly stronger magnetic fields, researchers dramatically amplify the signal, effectively increasing the chance that a photon will transform into a detectable boson and pass through an opaque barrier. This enhancement is crucial, as the expected interaction rates are incredibly low, requiring sensitive experiments and maximized conversion probabilities to distinguish potential signals from background noise. The technique, therefore, relies on precisely controlled, high-intensity magnetic fields to push the boundaries of particle detection and explore physics beyond the Standard Model.

The quest to detect faint interactions often hinges on the sophistication of the detection methods employed, and heterodyne detection represents a significant advancement in this area. This technique doesn’t simply register the presence of a signal, but actively mixes it with a local oscillator, effectively shifting the signal’s frequency to a more easily measurable range and amplifying its prominence against background noise. This process is crucial when searching for exceedingly weak signals, such as those predicted in axion research, where the interaction probability is incredibly low. By enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio, heterodyne detection allows researchers to discern true interactions from the inherent noise of the experiment, pushing the boundaries of sensitivity and opening new avenues for exploring phenomena beyond the reach of conventional methods. The improved sensitivity is not merely incremental; it enables the investigation of weaker signals and the potential discovery of particles previously considered undetectable.

The ALPS II experiment doesn’t merely search for axions; it actively refines the boundaries of what physics considers possible, establishing increasingly precise limits on hypothetical particle properties and informing the design of future investigations into particles beyond the Standard Model. Through meticulous data analysis, the experiment quantified various sources of uncertainty; technical noise, for example, fluctuated between 0.15% and 3.99% depending on data acquisition time, with the lowest values achieved during the S⟂ run. Calibration inconsistencies stemming from variations in open shutter measurements contributed a 7.0% uncertainty to the S∥ run, while the application of Savitzky-Golay filters introduced uncertainties of 0.45% and 2.2% for the S⟂ and S∥ runs respectively, demonstrating a commitment to rigorous error analysis and bolstering confidence in the established constraints on axion-like particles.

The meticulous calibration procedures detailed in this paper, aimed at minimizing systematic uncertainties in the ALPS II experiment, reveal a fundamental truth about the human condition. The search for particles shining through walls, while rooted in physics, mirrors a deeper quest to illuminate the unknown, a pursuit driven not by pure logic, but by an inherent hope that something lies beyond our current understanding. As Albert Camus observed, “In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.” This echoes in the dedication required to account for every potential error, every fluctuation – a belief in a signal that may be incredibly faint, yet still detectable with sufficient precision. All behavior is a negotiation between fear and hope, and this experiment is no different; the fear of missing a new phenomenon balanced by the hope of discovery. Psychology explains more than equations ever will.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The meticulous accounting of systematic uncertainty presented in this work isn’t about precision-it’s about acknowledging the inherent messiness of translating a theoretical hope into observable data. The search for light-shining-through-a-wall phenomena, like many ventures into beyond the standard model physics, rests on the assumption that an elegant solution exists. But humans aren’t driven by elegance; they’re driven by pattern recognition, and frequently mistake noise for signal. Calibration isn’t about correcting errors, it’s about creating a narrative that justifies the expenditure of resources.

Future iterations of this experiment, and others like it, will inevitably refine the technical aspects. Heterodyne detection will become more sensitive, optical cavities more stable. However, the fundamental limitation isn’t instrumental – it’s cognitive. The desire to find something will always outweigh the discipline to accept nothing. The true signal may not be a fleeting photon, but the persistent human need to fill the void of the unknown, even with self-deception.

The next logical step isn’t necessarily a larger detector or a more powerful laser. It’s a more honest assessment of the biases inherent in the search itself. A willingness to quantify not just the error in the measurement, but the error in the assumptions that drove the experiment in the first place. The universe isn’t hiding behind a wall of physics; it’s reflecting the flaws of those who seek to unveil it.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.18684.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Sunday Rose Kidman Urban Describes Mom Nicole Kidman In Rare Interview

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- The 10 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Enterprise

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- Amelia Finally Breaks Grey’s Anatomy’s Romance Curse In Season 22

2026-01-27 13:29