Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that even simple bistable systems exhibit predictable sampling behavior when initialized at their energy barrier, opening doors to novel computing architectures.

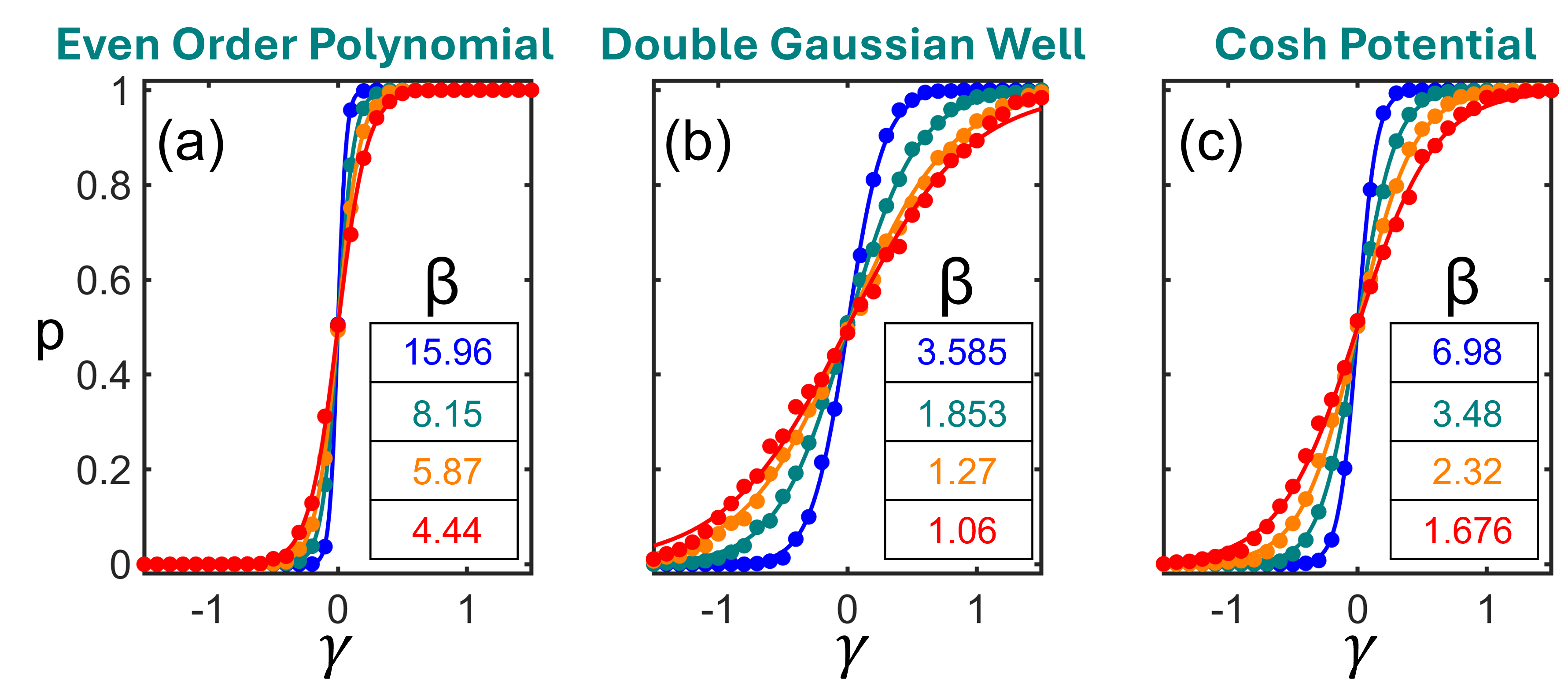

This study demonstrates that any double-well potential, when initialized near the barrier top, exhibits Boltzmann-like sampling, offering a pathway for synchronous, noise-driven computation.

The pursuit of hardware primitives for probabilistic computing faces the challenge of realizing robust and universal stochastic sampling mechanisms. This is addressed in ‘At the Top of the Mountain, the World can Look Boltzmann-Like: Sampling Dynamics of Noisy Double-Well Systems’, which reveals that initializing any smooth, even double-well potential near its energy barrier consistently produces Boltzmann-like sampling, independent of the potential’s detailed shape. This universality stems from a topologically robust, tanh-like response to noise and bias, offering a foundation for synchronous stochastic computation. Could this framework unlock scalable and efficient physical implementations of probabilistic bits across diverse platforms, from oscillators to magnetic devices?

Beyond Determinism: Embracing Uncertainty in Computation

Conventional computing systems are built upon deterministic bit operations, where each input invariably yields the same output. This approach, while remarkably effective for many tasks, struggles when confronted with the inherent uncertainty present in real-world phenomena. Many natural processes – from weather patterns and quantum mechanics to financial markets and biological systems – are fundamentally probabilistic, not absolute. Representing these systems with purely deterministic logic necessitates complex approximations and can lead to significant computational overhead, or even a loss of crucial information. The limitations become particularly pronounced when dealing with noisy data, incomplete information, or systems where randomness plays a central role; attempting to force probabilistic events into a deterministic framework often results in inaccurate models and unreliable predictions. Consequently, a new paradigm is needed to efficiently and accurately represent and process uncertainty, and this is where stochastic computing offers a compelling alternative.

Stochastic computing presents a compelling alternative to traditional, deterministic computation by embracing inherent uncertainty. Instead of relying on bits representing definitive 0 or 1 states, this paradigm utilizes probabilistic bits – representations where information is encoded as a probability distribution. This approach fundamentally alters how systems are modeled; rather than demanding precise calculations, it allows for the natural representation of systems where randomness or incomplete information is a core characteristic. Complex phenomena – from weather patterns and financial markets to biological processes and machine learning algorithms – often involve inherent uncertainties that are difficult to capture with deterministic methods. By directly encoding these uncertainties, stochastic computing enables a more intuitive and efficient representation of these systems, potentially unlocking novel computational strategies and offering significant advantages in modeling and prediction where traditional methods struggle.

The Boltzmann distribution, a cornerstone of statistical mechanics, provides the mathematical basis for representing probabilities within stochastic computing systems. This distribution, expressed as P(E) = \frac{e^{-E/kT}}{Z}, defines the likelihood of a system being in a particular state with energy E, where k is Boltzmann’s constant and T is the temperature. In the context of probabilistic computing, this translates to assigning probabilities to the states of stochastic bits, allowing for the modeling of inherent uncertainty. By leveraging this distribution, computations aren’t performed with fixed values, but rather through statistical sampling, where the frequency of a particular state represents its probability. This approach fundamentally alters computation, enabling the representation of imprecise information and facilitating the development of algorithms that can naturally handle noise and ambiguity, mirroring the behavior of many real-world systems.

The transition from deterministic computation to statistical sampling represents a fundamental shift in how machines process information. Instead of striving for exact solutions through precise calculations, this approach embraces inherent uncertainty by representing data and operations probabilistically. This allows systems to model complex phenomena-like weather patterns or financial markets-where exact prediction is impossible, but statistical inference is powerful. Novel computational strategies emerge, prioritizing the efficient generation of representative samples over definitive answers, and opening doors to algorithms that can learn and adapt in unpredictable environments. This paradigm isn’t about abandoning accuracy, but rather reframing it; the reliability of a result is measured not by its precision, but by the convergence and consistency of the statistical distribution from which it’s derived, offering a robust pathway for tackling previously intractable problems.

Physical Manifestations of Probabilistic Bits

Probabilistic bits can be realized physically using materials exhibiting double-well energy landscapes, a characteristic found in systems like CMOS bistable latches, ferroelectrics, and phase-transition oxides. In these materials, two stable states are separated by an energy barrier; thermal fluctuations allow the system to transition between these states with a probability determined by the barrier height and temperature. The probability of occupying each state is not strictly binary (0 or 1), but rather a value between 0 and 1, thus embodying the concept of a probabilistic bit. The shape and depth of the energy wells, along with the barrier separating them, directly influence the switching rate and the overall behavior of the p-bit.

The operation of physical probabilistic bits relies on the principle that all materials exhibit thermal fluctuations – random variations in energy due to temperature. These fluctuations provide the energy necessary for a bistable system, possessing two stable states, to overcome the energy barrier separating them. The probability of transitioning between these states is directly related to the magnitude of these fluctuations and the height of the energy barrier; higher temperatures and lower barriers increase the transition rate. This stochastic switching behavior effectively mimics the probabilistic nature of a bit, where the system exists in a superposition of states with associated probabilities, rather than definitively residing in a single state.

Low-barrier magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) are considered a strong candidate for physical probabilistic bit (p-bit) realization due to their ability to exhibit thermally-driven switching between resistance states. These devices consist of two ferromagnetic layers separated by a thin insulating barrier; the low energy barrier allows for frequent, stochastic transitions between parallel and anti-parallel magnetization configurations. Critically, the switching rate within an MTJ is tunable via several parameters, including barrier thickness, material composition, and applied magnetic field or current. This tunability is achieved by directly influencing the probability of overcoming the energy barrier via thermal activation, thus offering precise control over the bit’s stochastic behavior and allowing for optimization based on specific application requirements. The resistance difference between the two magnetic states directly represents the probabilistic value.

The functionality of physical probabilistic bits (p-bits) is fundamentally determined by the shape and characteristics of their underlying energy landscape. Specifically, p-bits are designed to exploit energy potentials featuring at least two stable states separated by an energy barrier; the height of this barrier directly impacts the bit’s retention time and switching probability. Controlling parameters like material composition, device geometry, and applied fields allows modulation of this energy landscape, thereby tuning the probability distribution of the bit’s state. A shallower barrier increases the switching rate but reduces retention, while a deeper barrier improves retention at the cost of slower switching. Precise control over the energy landscape is therefore crucial for realizing p-bits with desired performance characteristics, including specific bit error rates and switching speeds.

Dynamics Governing Stochastic Switching

Asynchronous p-bit switching relies on Kramers escape dynamics, a process where the system transitions between stable states by overcoming an energy barrier. The rate of this switching is strongly dependent on the height of this effective energy barrier, denoted as V. Lower barrier heights facilitate faster switching rates, as the probability of thermal or quantum tunneling increases. Conversely, higher barriers significantly reduce the switching probability, slowing the process. The escape rate, and thus the switching rate, is proportional to exp(-V/kT), where k is Boltzmann’s constant and T is the absolute temperature, demonstrating the exponential relationship between barrier height and switching speed. The shape of the potential well also influences the escape rate, but the barrier height remains a primary determinant in Kramers theory.

Synchronous switching, as opposed to thermally-driven asynchronous switching, necessitates overcoming the potential energy barrier separating stable states. This is commonly accomplished by applying an external drive, specifically a second-harmonic injection, which introduces an oscillating force at twice the natural frequency of the bistable system. This injected signal effectively tilts the potential energy landscape, reducing the effective barrier height and increasing the probability of transitioning between states with each cycle. The amplitude of the injected signal is a critical parameter; sufficient amplitude enables predictable, synchronized switching, while insufficient amplitude fails to drive transitions. This contrasts with asynchronous switching where transitions occur randomly due to thermal fluctuations overcoming the barrier.

Gradient flow dynamics describe the evolution of a system towards its stable equilibrium by following the steepest descent of its potential energy surface. This approach models the system’s behavior as a continuous flow governed by the negative gradient of the energy function, effectively representing the force driving the system towards a minimum energy state. The rate of relaxation is directly proportional to the magnitude of this gradient and inversely proportional to a damping factor representing energy dissipation. Mathematically, this can be represented as \frac{dx}{dt} = - \nabla U(x) - \gamma x, where U(x) is the potential energy, γ is the damping coefficient, and ∇ denotes the gradient operator. This framework allows for the prediction of the time required for the system to reach a stable state given the potential energy landscape and damping characteristics.

The A3 normal form simplifies the analysis of stochastic switching dynamics by representing the energy landscape as a double-well potential. This allows for a quantitative determination of the Mean First Passage Time (MFPT), which describes the average time required for the system to transition between potential wells. In the low noise limit, the MFPT is calculated as z_{th}/k_h, where z_{th} represents the threshold displacement and k_h is the harmonic curvature of the potential. Conversely, in the high noise limit, the MFPT is expressed as z_{th}^2/(2Kn), with K denoting the Kramers rate and n representing the noise intensity; this formulation demonstrates that switching speed is directly influenced by the height and curvature of the energy barrier, as well as the level of noise present in the system.

Implications for Stochastic Computation: A Path Forward

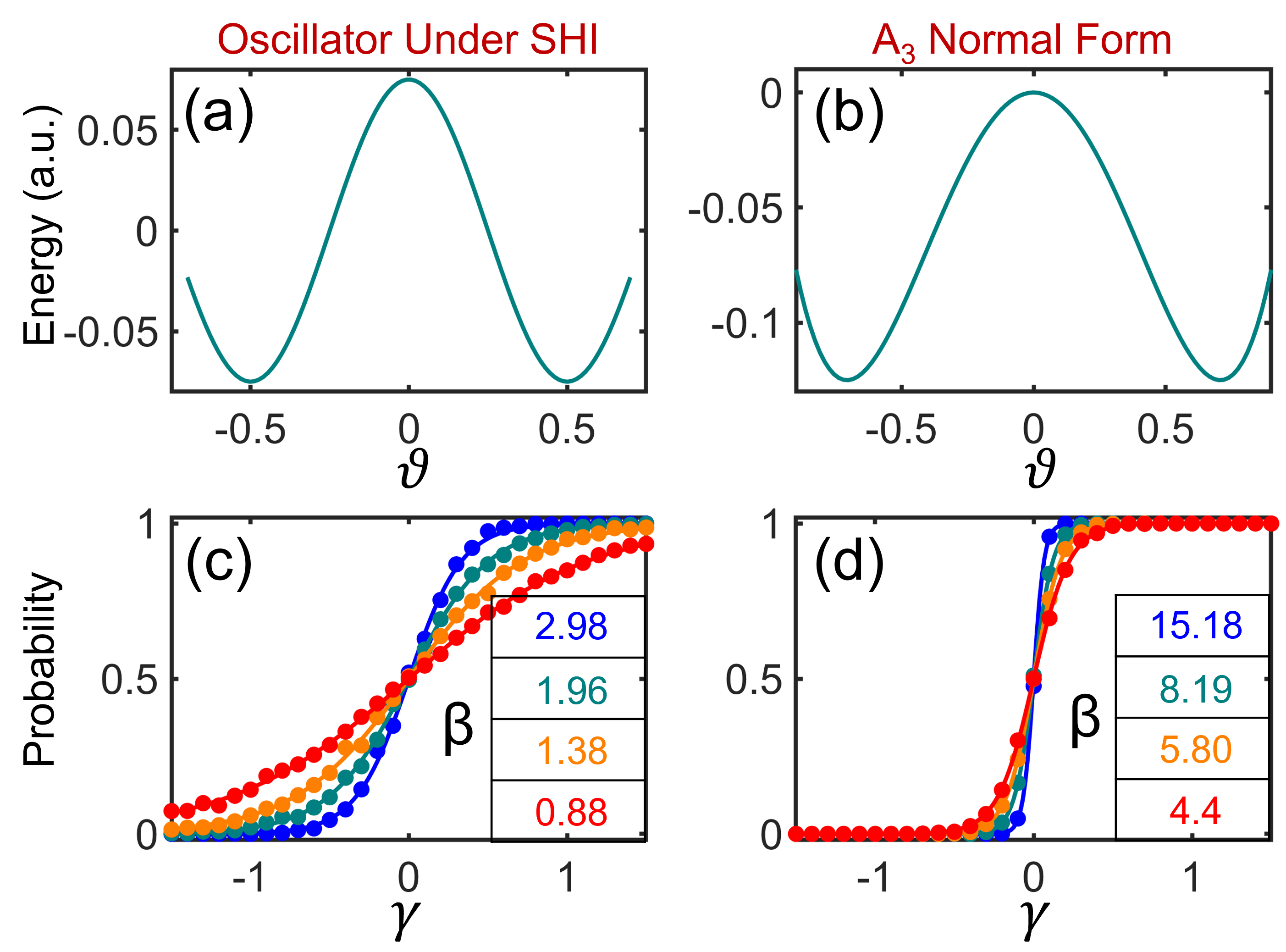

The realization of probabilistic bits, or p-bits, hinges on physical systems capable of embodying inherent randomness, and research indicates that oscillators subject to Stochastic Hybrid Integration (SHI) and relaxation oscillators offer a compelling pathway. These systems, characterized by a double-well energy landscape – envision a ball resting in one of two valleys – naturally transition between states due to stochastic forces, effectively representing the 0 and 1 of a p-bit. The frequency of switching between these potential wells, governed by the system’s parameters and noise, dictates the probability distribution of the p-bit’s state. By carefully engineering the double-well potential and controlling the noise characteristics, researchers can tune the oscillator to represent any desired probability distribution, laying the groundwork for novel computing architectures that exploit the power of stochasticity for enhanced efficiency and robustness.

The efficiency of stochastic computation hinges on how quickly a system transitions between states, and the Mean First Passage Time (MFPT) serves as a fundamental metric for quantifying this speed in synchronous modes of operation. Essentially, MFPT calculates the average time it takes for a system, starting from a defined initial state, to reach a specific target state for the first time. In the context of physical p-bit implementations – such as those leveraging the double-well potential of oscillators – a lower MFPT translates directly to faster sampling and, consequently, increased computational throughput. Researchers are actively exploring techniques to minimize MFPT through careful design of the potential energy landscape and control of system parameters, as this parameter critically influences the overall performance and energy efficiency of stochastic computing architectures. Understanding and optimizing MFPT is therefore paramount for realizing practical and scalable applications of these novel computational paradigms.

Stochastic sampling, a cornerstone of probabilistic computation, benefits significantly from the principles embodied within the Boltzmann Distribution, especially when dealing with inherent uncertainties in physical systems. Recent research demonstrates the viability of leveraging this distribution to achieve highly accurate sampling – exceeding 99% accuracy – in engineered systems. This has been rigorously validated through simulations that closely mirror theoretical predictions, as evidenced by R2 values consistently above 0.99 across a range of double-well potential functions. The fidelity of these simulations confirms that systems designed according to Boltzmann distribution principles can reliably navigate probabilistic landscapes, offering a robust foundation for developing advanced computational paradigms where uncertainty is not a hindrance, but a core operational element.

The demonstrated alignment between theoretical predictions and simulated Boltzmann sampling opens a significant pathway toward constructing energy-efficient stochastic computing architectures. Traditional computing relies on deterministic bit representations, demanding substantial energy for state transitions; stochastic computing, conversely, leverages probabilistic bit representations – p-bits – reducing energy consumption by embracing inherent uncertainty. This research establishes a physical foundation for implementing such p-bits using oscillating systems, specifically exploiting the double-well energy landscape for sampling. By accurately controlling the mean first passage time and aligning system behavior with the Boltzmann distribution, these architectures promise robustness against noise and manufacturing variations. The resulting systems could offer a paradigm shift in computation, particularly for applications demanding high energy efficiency and resilience, such as edge computing, sensor networks, and machine learning inference.

The study reveals a fundamental simplicity underlying complex systems. It demonstrates that even with noisy, bistable potentials, a predictable, Boltzmann-like sampling emerges when initialized at the barrier top. This echoes a core tenet of efficient design – reducing complexity to reveal inherent order. As Sergey Sobolev once stated, “The most difficult thing is to be simple.” This sentiment encapsulates the paper’s finding: a universal sampling mechanism arises not from intricate programming, but from a carefully considered initial condition. The authors skillfully illustrate how this principle might extend to a new synchronous computing paradigm, proving that elegance and efficiency often reside in the reduction, not the addition, of complexity.

The View From Here

The demonstration that Boltzmann-like sampling arises so readily from even simple bistable systems – initialized, crucially, at the precipice – feels less a discovery and more a correction. The field labored under assumptions of necessary complexity, seeking bespoke algorithms for stochastic computation. This work suggests the elegance lies in acknowledging the inherent tendency of such systems to gravitate towards the expected. The question, then, isn’t how to sample, but where to begin. The simplicity is almost unsettling.

Limitations remain, of course. The analysis, while conceptually clean, operates within idealized potentials. Real-world energy landscapes are rarely so… well-behaved. Noise characteristics, too, are assumed. The influence of correlated noise, or noise with non-Gaussian distributions, demands scrutiny. More pressingly, translating this principle into robust, scalable hardware presents significant engineering hurdles. Synchronous computation, while conceptually appealing, requires precise control – a delicate balance easily upset by practical imperfections.

Future work must address these deviations from the ideal. Perhaps the most fruitful avenue lies in exploring the boundaries of this universality. How robust is this Boltzmann-like behavior to asymmetries in the potential? Can it be extended to systems with more than two wells? The answer, one suspects, isn’t to build more complex models, but to refine the understanding of why such simple systems behave so predictably. The truth, as always, is likely staring back, disguised as obviousness.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04014.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Gold Rate Forecast

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- The 7 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Picard, Ranked

- Every Movie & TV Show Coming to Streaming Services This Weekend (October 31st)

2026-02-05 23:07