Author: Denis Avetisyan

A century after its inception, this review traces the fascinating history of Fermi-Dirac statistics and its profound impact on our understanding of the quantum world.

This article reconstructs the historical development of Fermi-Dirac statistics, from early monatomic gas theory to its crucial role in modern physics.

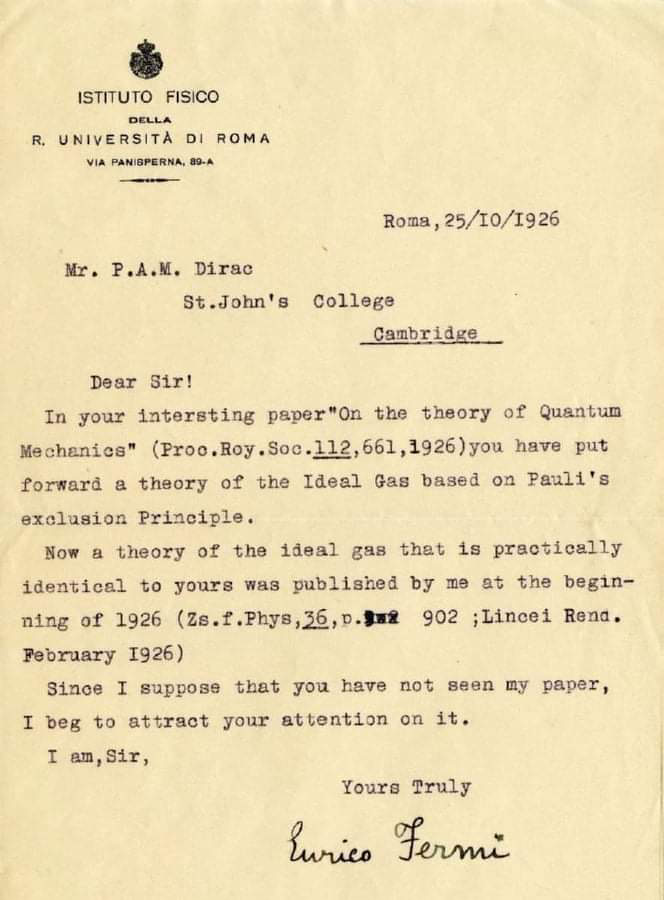

Early attempts to describe the behavior of identical particles within the framework of quantum mechanics faced inconsistencies with established thermodynamic principles. The paper ‘From Florence to Fermions: a historical reconstruction of the origins of Fermi’s statistics one hundred years later’ meticulously reconstructs the intellectual journey that led Enrico Fermi to develop his groundbreaking statistics, rooted in an application of the Exclusion Principle-originally conceived for atomic electrons-to systems of non-interacting particles. This work reveals how Fermi’s statistical framework, now known as Fermi-Dirac statistics, elegantly resolved these discrepancies and provided a foundation for understanding the properties of diverse systems, from 0-dimensional electron gases to stellar interiors. But how did the specific Florentine context of Fermi’s early research uniquely contribute to this pivotal advancement in quantum statistical mechanics?

The Impasse of Classical Description

At the dawn of the 20th century, physics faced a critical impasse in its attempt to fully characterize the behavior of matter. Classical mechanics, while successful in describing macroscopic phenomena, demonstrably failed when applied to the microscopic realm of atoms and their constituent particles. This deficiency wasn’t merely theoretical; a lack of accurate particle descriptions actively impeded progress in materials science. Properties like specific heat, electrical conductivity, and even the stability of matter itself remained poorly understood because the prevailing models couldn’t account for how particles interacted and distributed their energy. The inability to predict or explain these fundamental material characteristics underscored a deep need for a new theoretical framework, one that moved beyond the limitations of classical physics and embraced the peculiar behaviors observed at the atomic scale. This initial struggle laid the essential groundwork for the subsequent development of quantum mechanics and a revised understanding of the very building blocks of reality.

The burgeoning field of quantum mechanics arose from a fundamental discord between classical physics and experimental observations at the turn of the 20th century. Established physical models failed to accurately predict phenomena like blackbody radiation and the photoelectric effect, demanding a revised understanding of energy and matter. This prompted the development of the Old Quantum Theory, a patchwork of modifications to classical mechanics that, while ultimately superseded, provided a crucial stepping stone. Theorists introduced quantized energy levels and probabilistic descriptions of particle behavior – concepts radically different from the deterministic worldview of classical physics. Though internally inconsistent and lacking a comprehensive theoretical foundation, the Old Quantum Theory successfully explained many previously perplexing observations and paved the way for the more robust and mathematically complete formulations of quantum mechanics that followed, establishing a necessary, if temporary, framework for understanding the subatomic world.

A fundamental challenge in early quantum mechanics involved understanding how numerous identical particles – those indistinguishable from one another – behave collectively. Classical statistical mechanics, designed for macroscopic objects, failed to accurately predict the properties of matter at the atomic level. Physicists recognized the need for a new statistical framework capable of accounting for the wave-like nature of particles and the implications of quantum mechanics. This pursuit led to the development of two distinct statistical distributions: Bose-Einstein statistics, applying to bosons with integer spin, and Fermi-Dirac statistics, governing particles like electrons with half-integer spin. Enrico Fermi’s 1926 publication rigorously detailed the latter, outlining the behavior of fermions and establishing that no two identical fermions can occupy the same quantum state – a principle known as the Pauli exclusion principle. This work not only explained the electronic structure of atoms and the stability of matter, but also laid the foundation for understanding phenomena ranging from the conductivity of metals to the properties of white dwarf stars.

A Statistical Framework for Indistinguishable Particles

Prior to Enrico Fermi’s work, statistical mechanics largely relied on the classical Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and, to a lesser extent, Bose-Einstein statistics. These methods proved inadequate when applied to fermions – particles characterized by antisymmetric wavefunctions and governed by the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which dictates that no two identical fermions can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. Existing statistical approaches failed to account for this fundamental constraint, leading to inaccurate predictions of particle behavior at low temperatures and high densities. Fermi’s development of a new statistical framework directly addressed this limitation, providing a mathematically rigorous method for calculating the distribution of fermions in a system while explicitly incorporating the effects of the Pauli Exclusion Principle. This was crucial for accurately describing the properties of electrons in metals, nucleons in atomic nuclei, and other systems composed of fermionic particles.

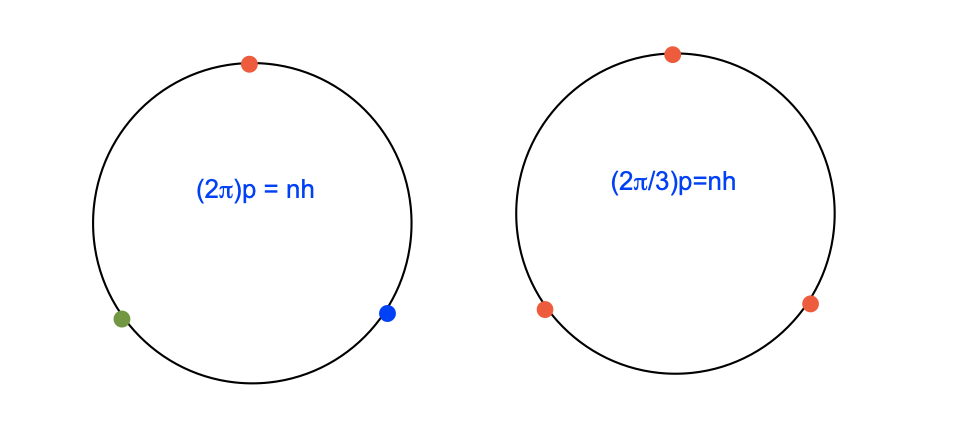

Fermi’s statistical method leveraged Arnold Sommerfeld’s quantization rules, which refined the Bohr model by introducing elliptical orbits and associated quantum numbers. This allowed for a more nuanced description of energy levels than previously available. Within the framework of phase space – a multidimensional space representing all possible states of a system – Fermi applied Sommerfeld’s quantization to determine the number of quantum states accessible to fermions. By integrating over phase space and accounting for the Pauli Exclusion Principle, the distribution function – defining the probability of finding a fermion in a particular state – could be calculated. This approach moved beyond classical statistical mechanics by acknowledging the discrete nature of energy levels and the indistinguishability of identical fermions, offering a pathway to predict material properties dependent on fermionic behavior.

Prior to Fermi’s statistical method, the Sackur-Tetrode equation provided an approximation for the entropy of a monatomic ideal gas, treating particles as distinguishable and largely ignoring quantum effects. Fermi’s extension, however, incorporated the principles of quantum mechanics and accounted for particle indistinguishability, crucial for systems containing fermions. This resulted in a more accurate calculation of thermodynamic properties, particularly at low temperatures and high densities where classical approximations failed. By correctly describing the energy distribution of fermions, Fermi statistics provided quantitative agreement with experimental observations that the Sackur-Tetrode formula could not achieve, improving the precision of calculations for systems like electron gases in metals and degenerate stellar matter.

Fermi Statistics, developed as an extension of existing quantum statistical methods, proved particularly effective in describing the behavior of fermions – particles with half-integer spin that obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle. While initially formulated to address the limitations of classical statistics when applied to systems of indistinguishable particles, its initial practical demonstration occurred through the analysis of bosonic systems, specifically liquid Helium. This seemingly counterintuitive application highlighted the broader applicability of the statistical framework; although derived for fermions, the mathematical structure of Fermi Statistics provided a more accurate model for Helium’s properties at extremely low temperatures than the previously utilized Bose-Einstein statistics could provide, revealing subtle differences in the behavior of bosons at high densities.

Predictive Power: Modeling Material Behavior

The application of Fermi-Dirac statistics was pivotal in developing the free electron model, commonly known as the Electron Gas. This model treats electrons within a solid as a gas of non-interacting fermions, obeying the Pauli Exclusion Principle which dictates that no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state. Unlike classical Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics which assume particles are distinguishable, Fermi statistics accounts for the indistinguishability of electrons and their fermionic nature, significantly impacting predictions of electron distribution and energy levels within materials. The resulting statistical distribution, the Fermi-Dirac distribution function, f(E) = \frac{1}{e^{(E-E_F)/kT} + 1}, where E_F is the Fermi energy, accurately describes the probability of an electron occupying a given energy state at a specific temperature T and explains properties such as electrical conductivity and heat capacity in metals.

The Fermi Level, denoted as E_F, represents the highest occupied energy state in a system of fermions at absolute zero temperature. Derived from Fermi-Dirac statistics, it defines a critical energy threshold: at 0 Kelvin, all energy states below E_F are filled, and all states above are empty. At temperatures above absolute zero, the Fermi Level indicates the energy at which the probability of occupancy is exactly 50%. This level is not a property of individual electrons, but rather a characteristic of the entire electron system within a solid, and is crucial for determining electrical conductivity, thermal properties, and other key behaviors in materials. The position of the Fermi Level relative to the band structure of a material dictates whether it will behave as a conductor, insulator, or semiconductor.

Semiconductors, materials with conductivity between conductors and insulators, are accurately modeled using Fermi-Dirac statistics due to the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons within their energy bands. The position of the Fermi level – E_F – relative to the valence and conduction bands dictates the material’s electrical properties; in semiconductors, E_F lies within the band gap. The concentration of electrons and holes, the charge carriers in semiconductors, is directly determined by the Fermi level and temperature, enabling precise prediction of conductivity. This statistical approach is essential for understanding and designing semiconductor devices like transistors and diodes, forming the basis of modern electronic circuitry and allowing for control of current flow through doping and external fields.

Prior to the development of Fermi-Dirac statistics, descriptions of material behavior relied heavily on classical physics, which posited continuous energy distributions and failed to accurately predict observed phenomena like heat capacity and electron conductivity. The application of Fermi statistics, derived from quantum mechanics, introduced the concept of discrete energy levels and the Pauli exclusion principle, fundamentally altering the understanding of particle behavior within materials. This allowed for the accurate modeling of electron distributions, explaining why electrons do not simply occupy the lowest energy states and providing a framework to predict material properties based on electron configurations. The resulting quantum mechanical descriptions accurately reflected experimental observations at low temperatures and high densities where classical models failed, demonstrating a significant advancement in characterizing the fundamental properties of matter.

Beyond Conventional Matter: Implications for Exotic States

The seemingly paradoxical formation of Cooper Pairs-bound states of electrons that overcome their mutual electrostatic repulsion-finds its explanation within the principles of Fermi statistics. This statistical framework, governing identical particles with half-integer spin like electrons, dictates that no two can occupy the same quantum state. However, a subtle interplay arises when considering electron interactions with the crystal lattice of a material. One electron subtly distorts the lattice, creating a region of positive charge that, in turn, attracts another electron. This indirect attraction, mediated by lattice vibrations known as phonons, can overcome the direct Coulomb repulsion, effectively lowering the overall energy when the electrons pair up. Crucially, this pairing isn’t a simple matter of electrons ‘sticking’ together; rather, the paired electrons behave as a composite boson-a particle governed by Bose statistics-allowing many pairs to occupy the same quantum state and flow without resistance, thus enabling the phenomenon of superconductivity. \Psi(r_1, r_2) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} [\Psi_{\uparrow}(r_1)\Psi_{\downarrow}(r_2) - \Psi_{\downarrow}(r_1)\Psi_{\uparrow}(r_2)] represents a simplified wavefunction for a Cooper pair, highlighting the anti-symmetric nature required by Fermi statistics.

Superconductivity, a remarkable state where materials conduct electricity with absolutely no resistance, hinges on the formation of Cooper pairs. These pairs arise from a quantum mechanical phenomenon where two electrons, normally repelled by each other, become weakly bound together through interactions with the material’s lattice vibrations – phonons. This pairing overcomes the usual resistance to electron flow; instead of colliding with atoms and losing energy, the Cooper pairs move through the material as a single entity, a coherent wave function. The strength of this pairing determines the temperature at which superconductivity emerges, with materials needing to be cooled below a critical temperature for the effect to manifest. This ability to conduct electricity without loss has immense potential, ranging from lossless power transmission to incredibly sensitive magnetic resonance imaging, all rooted in the peculiar behavior of these electron duets.

Theoretical physics posits that under conditions of immense density and energy – such as those believed to exist within neutron stars or immediately after the Big Bang – a state of matter known as color superconductivity may arise. Analogous to conventional superconductivity where electrons pair up, in color superconductivity, quarks – the fundamental constituents of protons and neutrons – are predicted to form Cooper pairs. However, unlike electrons repelled by each other, quarks interact via the strong nuclear force, exhibiting a property called ‘color charge’. These color charges dictate the pairing mechanism, resulting in a fundamentally different type of superconductivity where electrical resistance vanishes not for electrons, but for the collective flow of color-charged quarks. The existence of color superconductivity remains unproven experimentally, but its theoretical framework offers profound insights into the behavior of matter at extreme densities and provides a compelling connection between particle physics and condensed matter physics, potentially reshaping understanding of neutron stars’ interiors and the early universe.

The principles initially established by Fermi’s statistics continue to resonate within contemporary condensed matter physics, extending far beyond their original application to simple electron systems. Investigations into exotic states of matter, such as superconductivity and the theoretically predicted color superconductivity involving quarks, rely fundamentally on the understanding of particle pairings and their collective behavior as described by Fermi-Dirac statistics. These advanced explorations aren’t merely extensions of an old theory, but rather demonstrations of its surprising robustness and adaptability to increasingly complex physical scenarios. The enduring relevance of Fermi’s work underscores its position as a cornerstone of modern materials science, continually inspiring new avenues of research into the fundamental properties of matter and paving the way for potentially revolutionary technologies.

The historical reconstruction detailed within necessitates a rigorous assessment of foundational principles, echoing the pursuit of immutable truths within physics. It is fitting, then, to consider Ernest Rutherford’s assertion: “If you can’t account for something, it’s not magic, it’s just bad physics.” This sentiment directly aligns with the paper’s endeavor to meticulously trace the development of Fermi-Dirac statistics, moving beyond phenomenological observations to a mathematically grounded understanding of particle behavior. The evolution from classical models to quantum descriptions, as the article demonstrates, isn’t a shift in mystery, but a refinement of explanatory power, demanding logical consistency and predictive accuracy. The very foundation of statistical mechanics rests upon precisely this principle – a complete and verifiable accounting of physical phenomena.

The Road Ahead

The reconstruction of Fermi’s statistics, as presented, is not merely an exercise in historical accounting. It reveals a persistent tension: the desire for wholly predictive models versus the inherent probabilistic nature of quantum systems. While the Fermi-Dirac distribution elegantly describes a wide range of phenomena, its foundations rest on approximations – the ideal monatomic gas, the assumption of non-relativistic particles. The consistency of these assumptions, when stretched to describe increasingly complex systems, deserves further scrutiny.

A critical path forward lies in a more rigorous treatment of many-body interactions. The independent particle approximation, while computationally convenient, introduces a systematic error. Developing methods to accurately account for electron correlation – to move beyond the mean-field approach – remains a substantial challenge. The pursuit of provably accurate solutions, not merely empirically successful ones, is paramount.

Furthermore, the application of Fermi-Dirac statistics to emergent phenomena – such as the behavior of quasiparticles in condensed matter systems or the dynamics of fermionic condensates – requires a careful re-evaluation of its underlying assumptions. The statistical mechanics must be demonstrably consistent across varying energy scales and dimensionality. The elegance of the formalism demands no less.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04484.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Auto 9 Upgrade Guide RoboCop Unfinished Business Chips & Boards Guide

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

- Goat 2 Release Date Estimate, News & Updates

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- One of the Best EA Games Ever Is Now Less Than $2 for a Limited Time

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

- Marvel Rumor Teases Robert Downey Jr’s Doctor Doom Future After Secret Wars

2026-02-06 02:25