Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how competing magnetic interactions can create complex, multi-state spin arrangements with potentially unique electronic properties.

The study demonstrates that combinations of biquadratic and spiral-staggered exchange interactions stabilize multiple-Q spin textures in one-dimensional itinerant magnets, leading to antisymmetric spin splitting and asymmetric band modulation.

While conventional magnetism often focuses on single-wavevector orderings, complex spin textures with multiple, symmetry-unrelated ordering wavevectors remain a fascinating challenge. This work, ‘Multiple-$Q$ spin textures induced by spiral–staggered interference in one-dimensional itinerant magnets’, theoretically demonstrates that a combination of competing exchange interactions and positive biquadratic anisotropy can stabilize such multiple-$Q$ states in one-dimensional systems. Specifically, the superposition of spiral and staggered modulations leads to robust double-$Q$ magnetic structures exhibiting unique electronic properties, including antisymmetric spin splitting. Could these findings unlock new avenues for designing and controlling complex magnetic materials with tailored electronic functionalities?

Beyond Simple Order: The Emergence of Complex Magnetism

Many materials exhibit magnetic behavior far exceeding the predictions of simple models based on single-spin modulation, such as the Single-QQ state. This traditional framework, while useful as a starting point, often overlooks the intricate interplay of magnetic moments that arise from complex crystal structures and competing interactions. Real materials frequently present multiple, superimposed spin patterns – a deviation from the idealized single modulation – leading to discrepancies between theoretical predictions and experimental observations. The limitations of the Single-QQ state become particularly apparent when studying materials with complex compositions or those subjected to external stimuli like pressure or temperature changes, highlighting the need for more nuanced approaches to accurately describe their magnetic properties and unlock their full potential.

The discovery of Multiple-QQ magnetic states necessitates a shift beyond traditional theoretical frameworks, as these states arise from the superposition of distinct spin modulation patterns. Unlike simpler magnetic orderings described by a single \mathbf{q} vector, Multiple-QQ states are characterized by the coexistence of multiple, incommensurate wavevectors, creating complex interference patterns within the material’s magnetic structure. Accurately modeling these states demands techniques capable of capturing the interplay between these competing modulations, often requiring advanced computational methods and a departure from the simplifying assumptions inherent in single- \mathbf{q} descriptions. This increased complexity, while presenting a theoretical challenge, also hints at the possibility of emergent phenomena and functionalities unattainable in materials governed by simpler magnetic orderings.

The discovery of Multiple-QQ magnetic states extends beyond merely cataloging complex magnetic arrangements; it hints at a wealth of previously unrealized functionalities. These states, arising from the superposition of distinct spin modulations, present opportunities for tailoring material properties in ways not achievable with simpler magnetic orders. However, fully realizing this potential necessitates computational approaches exceeding those traditionally employed. Accurate modeling demands techniques capable of handling the intricate interplay between multiple, competing magnetic orders, often requiring sophisticated algorithms and substantial computational resources. Researchers are actively developing and refining these advanced modeling techniques-including those leveraging machine learning and high-performance computing-to predict, understand, and ultimately harness the unique properties embedded within these complex magnetic landscapes, paving the way for novel spintronic devices and materials with tailored functionalities.

Unraveling Interactions: Modeling Complexity in Magnetic Systems

Real-space spin models and momentum-resolved spin models represent distinct but complementary methodologies for characterizing magnetic interactions within materials. Real-space models, such as the Heisenberg or Ising models, directly analyze the spatial arrangement of spins and the interactions between neighboring magnetic moments; this approach excels at revealing local magnetic order and identifying specific exchange pathways. Conversely, momentum-resolved spin models operate in reciprocal space, typically utilizing techniques like neutron scattering to determine the magnetic structure and excitation spectra as a function of momentum transfer \textbf{q}. By analyzing data in momentum space, these models provide insights into long-range magnetic order, spin wave behavior, and the overall magnetic susceptibility of the material. Combining the localized information from real-space models with the extended information from momentum-resolved models allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay of magnetic interactions.

Magnetic interactions are not limited to simple ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic coupling; both bilinear and biquadratic exchange interactions are essential for accurately modeling complex magnetic phenomena. Bilinear exchange, represented as J_1 \sum_{<i,j>} \mathbf{S}_i \cdot \mathbf{S}_j, describes the classical pairwise interaction between neighboring spins \mathbf{S}_i and \mathbf{S}_j. However, biquadratic exchange, expressed as K \sum_{<i,j>} (\mathbf{S}_i \cdot \mathbf{S}_j)^2, arises from higher-order interactions or quantum effects, and significantly alters the magnetic behavior. Specifically, biquadratic exchange can promote non-collinear spin arrangements and influence the stability of various magnetic phases, including spin-glass and re-entrant spin-glass states, which are not captured by bilinear models alone. Therefore, inclusion of both interaction terms is crucial for a complete understanding and accurate modeling of complex magnetic materials.

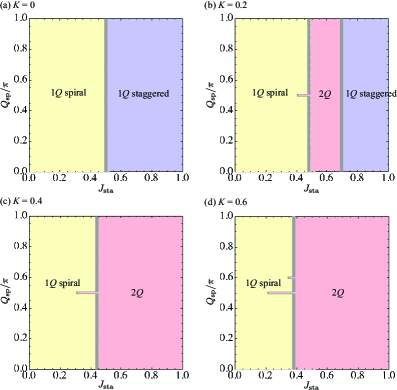

Simulated annealing is employed to refine the accuracy of magnetic interaction models by systematically reducing the temperature of the system to achieve low-energy, equilibrium configurations. Calculations are performed on systems containing N=200 spins, allowing for statistically relevant data collection. The annealing process utilizes a temperature range of 1.0 to 0.001, with incremental temperature decreases facilitating the exploration of the configuration space and minimizing the risk of becoming trapped in local energy minima. This controlled cooling schedule ensures the final spin arrangement represents a stable, low-energy state indicative of the dominant magnetic interactions within the modeled material.

A Case Study: The Broken Helix State and its Origins

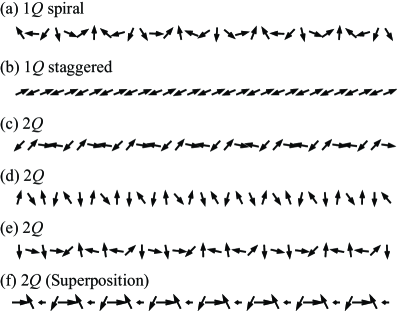

The Broken Helix State observed in EuIn2As2 is a representative example of a Multiple-QQ state, distinguished by the simultaneous presence of helical and staggered spin modulations. This means the magnetic moments within the material do not align in a single, simple pattern; instead, two distinct wave vectors, or “Q” values, define the spin structure. One wave vector describes a helical ordering where spins rotate around an axis, while the other describes a staggered ordering where spins alternate in direction. The coexistence of these two modulations results in a complex magnetic structure, differing from single-Q helical or staggered states, and contributing to the unique magnetic characteristics of EuIn2As2.

The Broken Helix State in EuIn2As2 represents an extension of the Double-QQ state, fundamentally characterized by the superposition of multiple incommensurate wave vectors \mathbf{q}_1 and \mathbf{q}_2. This superposition leads to a complex spin modulation where the magnetic moments are not aligned along a single direction, but rather exhibit a pattern resulting from the interference of these wave vectors. Consequently, the material displays unique magnetic properties, including a reduced magnetic ordering temperature and a modified excitation spectrum compared to single-\mathbf{q} magnetic structures. The resulting magnetic structure is not simply the sum of individual helical orderings, but a novel arrangement dictated by the interplay between the superimposed wave vectors and the underlying crystal structure.

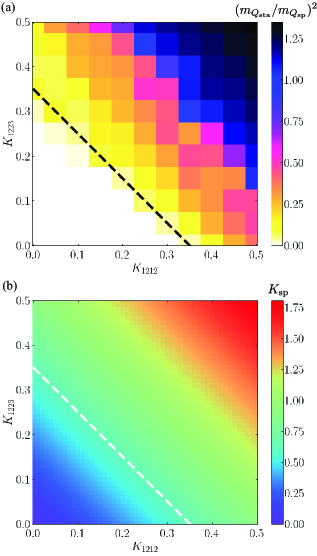

Computational modeling, employing the techniques detailed previously, has validated the stability of the Broken Helix State observed in EuIn2As2. These investigations confirm that the observed magnetic structure arises from the superposition of wave vectors characteristic of a double-QQ state. Specifically, the simulations demonstrate a crucial dependence on the biquadratic exchange interaction; a positive value for this interaction is essential for stabilizing the double-QQ configuration and preventing a transition to a simpler magnetic order. The calculated energy landscape and spin configurations align with experimental observations, further supporting the role of the biquadratic interaction in determining the magnetic properties of EuIn2As2.

Electronic Roots: The Interplay Between Band Structure and Magnetic Order

The stability and nuanced behavior of complex magnetic states, such as the enigmatic Double-QQ state, are fundamentally dictated by the material’s electronic band structure. This structure, which maps the allowed energy levels for electrons within the solid, doesn’t merely provide a backdrop for magnetism; it actively shapes it. The arrangement of electron orbitals and their resulting energy bands determine the strength and nature of exchange interactions between magnetic moments. Specifically, features like the density of states near the Fermi level and the bandwidth of relevant orbitals directly influence the preference for particular magnetic orderings. A band structure that favors specific spin configurations will naturally lead to a more stable magnetic state, while alterations to this structure – through chemical composition or external pressure – can induce transitions between different magnetic phases or even drive the emergence of novel magnetic textures. Understanding this interplay is crucial not only for explaining existing magnetic phenomena but also for designing materials with tailored magnetic properties.

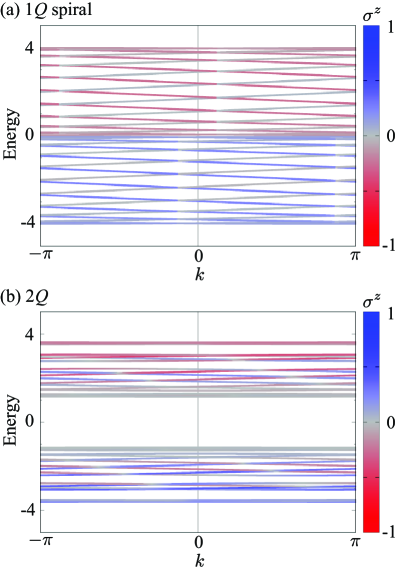

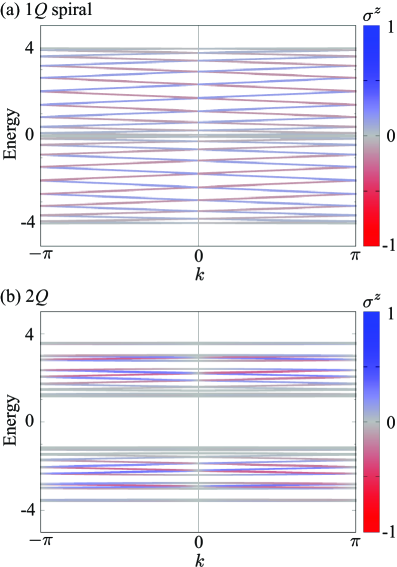

Investigations into complex magnetic systems reveal a profound connection between a material’s electronic behavior and its magnetic order, manifested through antisymmetric spin splitting and asymmetric band modulation. This interplay isn’t merely correlative; the emergence of these electronic features is directly tied to the specific magnetic arrangement. Antisymmetric spin splitting, where the spin of electrons is lifted in a non-uniform manner, arises from the broken symmetry inherent in the magnetic order. Simultaneously, asymmetric modulation of the electronic bands – changes in the energy and distribution of electrons – further reinforces and is reinforced by the magnetic configuration. These findings demonstrate that magnetism isn’t simply imposed on the electronic structure, but actively shapes and is shaped by it, suggesting a unified origin for both phenomena and opening avenues for materials design with tailored magnetic and electronic properties.

The Ruderman-Kittel-Kasuya-Yosida (RKKY) interaction offers a fundamental understanding of how electronic structure dictates magnetic ordering, specifically explaining the origin of bilinear exchange interactions. This interaction arises from the indirect exchange of spin polarization between magnetic moments through conduction electrons; a given magnetic ion polarizes the electron sea, and this polarization, in turn, affects the spin of another magnetic ion. The strength and sign of this interaction – whether it favors ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic alignment – are profoundly sensitive to the density of states at the Fermi level and the spacing between magnetic ions, effectively linking the electronic band structure to the observed magnetic behavior. Consequently, RKKY interactions provide a microscopic basis for predicting and controlling magnetic properties in materials, demonstrating that magnetism isn’t merely an emergent phenomenon but is deeply rooted in the underlying electronic structure of the material.

The emergence of multiple-QQ spin textures, as demonstrated in this research, exemplifies how complex order arises not from imposed control, but from the interplay of local interactions. Specifically, the balance between biquadratic interactions and competing spiral and staggered exchange interactions dictates the final spin configuration. This mirrors the principle that order manifests through interaction, not control. As Karl Popper observed, “The more we try to explain things, the more we realize how little we know.” This study, revealing previously unconsidered symmetry-unrelated spin textures, acknowledges the limits of pre-defined expectations, highlighting the power of allowing systems to self-organize within defined parameters.

Beyond the Helix

The stabilization of multiple-$Q$ spin textures, as demonstrated in this work, isn’t merely a matter of finding the right ingredients – positive biquadratic interactions alongside competing exchange – but acknowledging the inherent inventiveness within constraints. Attempts to force a single magnetic order often reveal only the most obvious solutions. Instead, allowing the system to navigate the interplay of these interactions generates a far richer landscape of possibilities, a point often lost in the pursuit of precisely engineered materials. The resulting antisymmetric spin splitting and asymmetric band modulation are not design features, but emergent properties – a consequence of relinquishing control.

Future investigations shouldn’t focus on optimizing these textures for specific applications, but on exploring the broader implications for itinerant magnetism. The model presented here offers a fertile ground for studying the interplay between spin chirality and electronic topology. It remains to be seen whether similar principles govern the formation of more complex spin textures in higher dimensions, or whether these systems can be harnessed – not controlled – to realize novel quantum phenomena. The true challenge lies not in dictating magnetic order, but in understanding the rules by which order spontaneously arises.

Simulated annealing, while effective in this instance, represents a brute-force approach. A more profound understanding will require analytical frameworks capable of predicting the stability of these textures a priori. This will necessitate a shift from viewing magnetic interactions as parameters to be tuned, to recognizing them as the local rules governing a self-organizing system. The system doesn’t need an architect; it finds its own equilibrium.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09267.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- One of the Best EA Games Ever Is Now Less Than $2 for a Limited Time

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Felicia Day reveals The Guild movie update, as musical version lands in London

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

2026-01-15 23:44