Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research utilizing nuclear emulsions provides crucial insights into the relativistic dissociation of nuclei and the elusive Hoyle state, shedding light on the formation of carbon and heavier elements.

This study investigates alpha clustering and unstable states in the dissociation of relativistic nuclei, including 8Be and 12C, using invariant mass spectroscopy.

Despite longstanding interest in nuclear clustering, understanding the formation and properties of unstable resonant states remains a significant challenge. This is addressed in ‘The $^{8}$Be nucleus and the Hoyle state in dissociation of relativistic nuclei’, which details an analysis of relativistic nuclear dissociation using high-resolution nuclear emulsions to probe exotic states. The study identifies contributions from ^{8}\text{Be}, ^{9}\text{Be}, ^{12}\text{C} resonances, suggesting a coalescence mechanism involving alpha particles and nucleons, potentially revealing signatures of low-energy fusion reactions. Could this approach, combined with modern accelerator facilities like the JINR NICA complex, unlock new insights into the equation of state of nuclear matter and the origins of elements in astrophysical environments?

The Delicate Dance of Creation: Carbon in the Cosmos

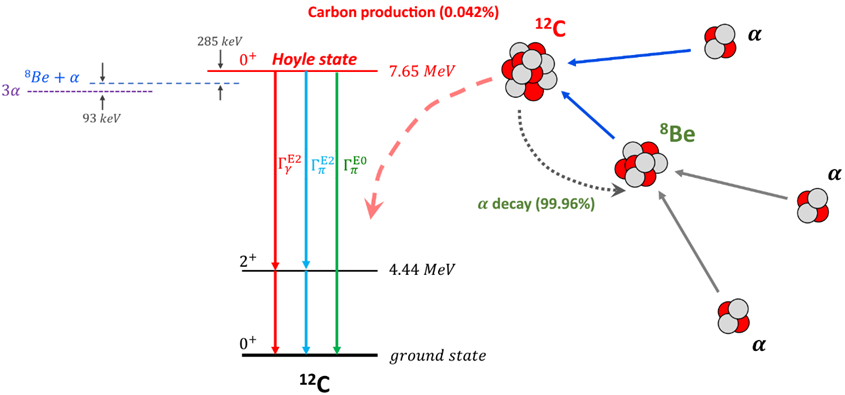

The creation of carbon within stars, a process known as the Triple-Alpha Process, remains one of the most significant unsolved problems in astrophysics. Carbon, the backbone of all known life, isn’t forged from the direct fusion of smaller nuclei, but rather through a two-step process where two helium nuclei ( ^4He ) first fuse to form beryllium-8 ( ^8Be ), an extremely unstable nucleus. This fleeting beryllium-8 then quickly combines with another helium nucleus to produce stable carbon-12 ( ^{12}C ). The rarity of this sequence, reliant on a brief window of beryllium-8 stability and the low probability of three-body interactions, has puzzled scientists for decades; the universe appears delicately balanced to allow for sufficient carbon production, prompting questions about the fundamental constants of nature and the conditions necessary for life’s emergence.

The creation of carbon atoms within stars isn’t a straightforward fusion, but rather a delicate dance involving alpha clustering – the tendency of protons and neutrons, known collectively as nucleons, to bind together as alpha particles (^4He) . This isn’t simply a matter of nucleons randomly colliding; instead, specific energy levels within the nucleus favor the formation of these stable alpha groupings. These clusters then act as intermediary building blocks, facilitating the fusion process necessary for carbon synthesis. The rarity of this phenomenon stems from the fleeting existence of certain nuclei, like beryllium-8, which briefly forms from two alpha particles before decaying, demanding precisely tuned conditions within stellar cores to allow for sustained clustering and, ultimately, the creation of heavier elements essential for life.

The accurate modeling of stellar nucleosynthesis – the creation of heavier elements within stars – fundamentally depends on a thorough comprehension of alpha clustering. This phenomenon, where nucleons arrange themselves into alpha particles (^4He) , isn’t merely a detail, but a critical step in forging carbon, oxygen, and all subsequent elements essential for life. Without precisely accounting for how readily these alpha particles form and interact within the extreme conditions of stellar cores, simulations of element creation become unreliable. Consequently, a refined understanding of alpha clustering directly impacts our ability to trace the origins of the building blocks of life – carbon in particular – from the earliest stars to the formation of planets and, ultimately, to the emergence of biological complexity. The rate at which these clusters form dictates the abundance of elements throughout the universe, influencing the very conditions necessary for habitability.

The formation of heavier elements within stars hinges on the fleeting existence of alpha clusters – groups of two protons and two neutrons – but achieving sustained alpha clustering is hindered by the inherent instability of certain intermediate nuclei, most notably ^{8}Be. Beryllium-8, formed from two alpha particles, exists for only a minuscule fraction of a second before decaying, presenting a significant bottleneck in the nuclear reactions that forge carbon. This rapid decay rate dramatically reduces the probability of a third alpha particle fusing with ^{8}Be to create stable ^{12}C, the cornerstone of life as it is known. Consequently, the rate of the Triple-Alpha process is surprisingly sensitive to the energy levels within ^{8}Be, demanding precise understanding of this ephemeral nucleus to accurately model stellar nucleosynthesis and the cosmic abundance of carbon.

Dissecting the Nucleus: Probing for Alpha Clusters

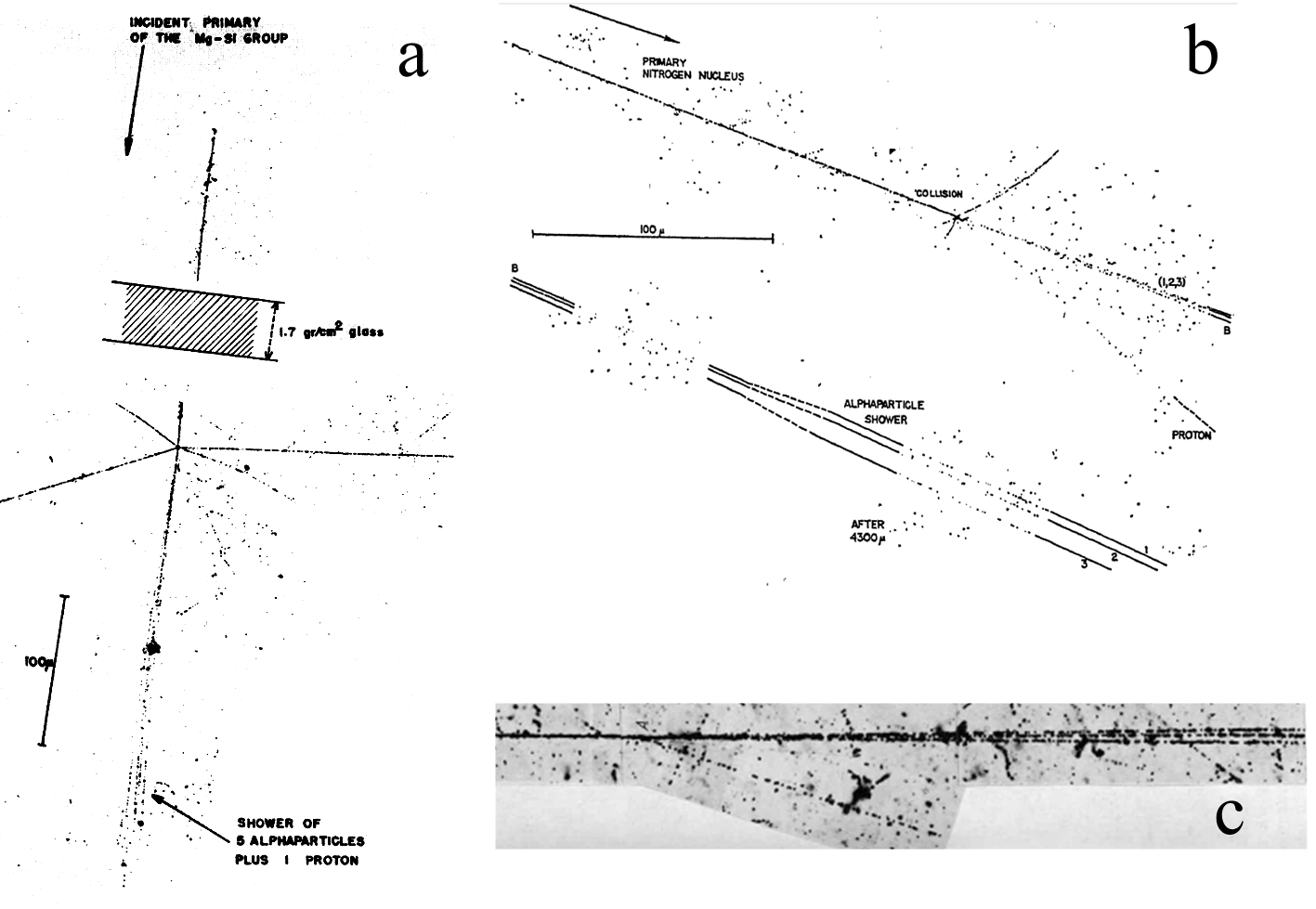

Nuclear fragmentation, achieved by bombarding target nuclei with high-energy beams – commonly proton beams – provides a means to investigate the presence and characteristics of alpha clustering. This technique relies on the decomposition of the target nucleus into lighter fragments, where the observation of these fragments – their types and emission probabilities – reveals information about the original nuclear structure. Specifically, the prevalence of alpha-sized fragments ( ^4He ) in the fragmentation products indicates a tendency for the nucleus to clusterize into alpha particles. By analyzing the energy and angular distributions of these fragments, researchers can deduce the strength of the alpha clustering and the associated nuclear states, offering insights into the many-body correlations within the nucleus.

The analysis of fragments produced during nuclear fragmentation, such as the observation of 9B and 10C nuclei, allows for inferences regarding the original nucleus’s structure. These fragments represent portions of the parent nucleus ejected during the high-energy collision, and their yield, energy, and angular distribution are sensitive to the arrangement of nucleons within the original nucleus. Specifically, the presence and abundance of certain fragments can indicate the existence of pre-formed clusters – notably alpha particles – within the nucleus before fragmentation occurred. By comparing experimental fragment distributions with theoretical models based on different nuclear structures, researchers can validate or refine our understanding of nuclear organization and stability.

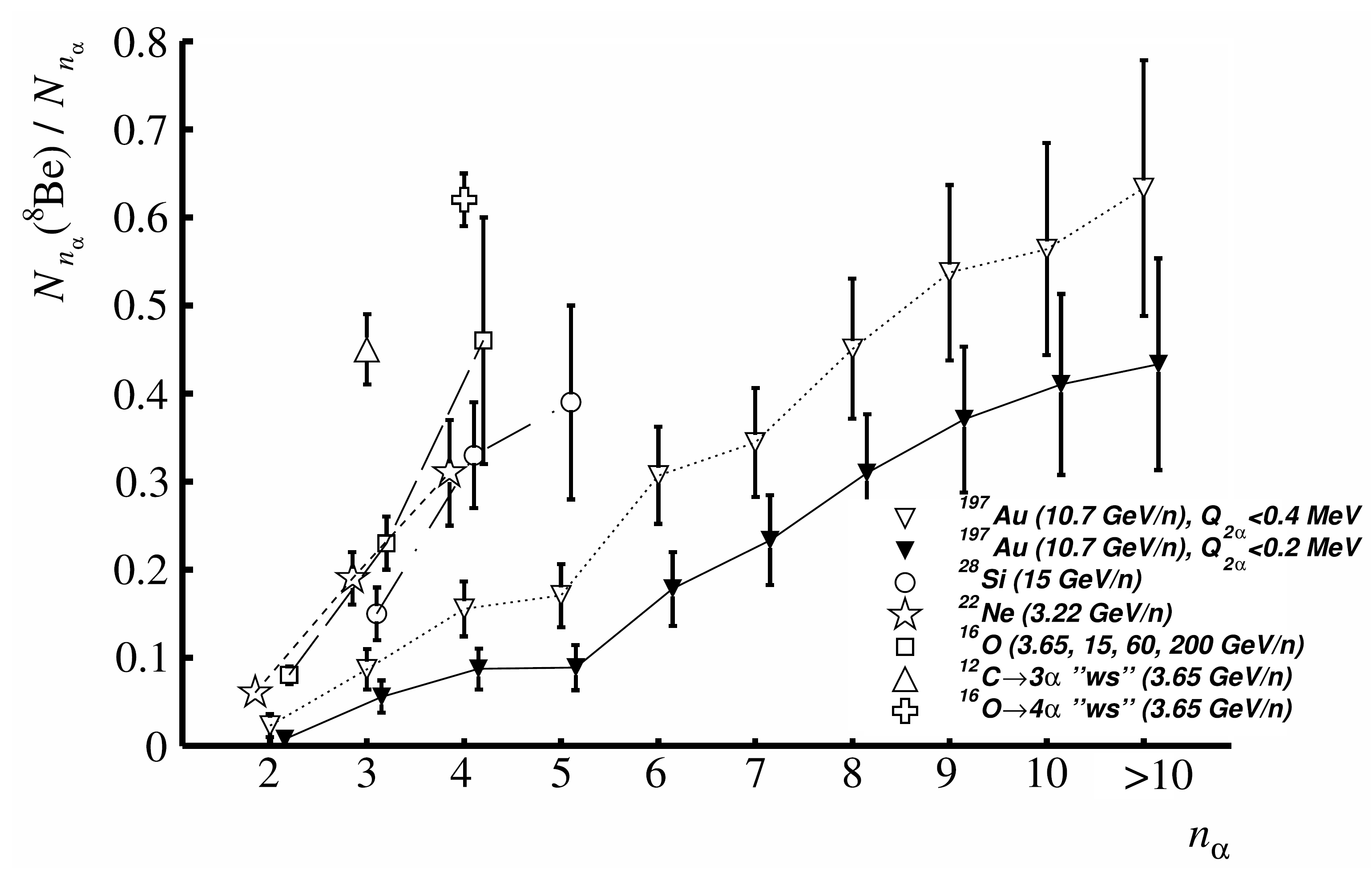

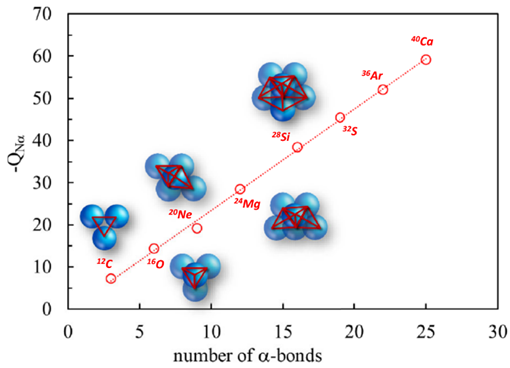

The detection of specific fragment combinations following nuclear fragmentation directly supports the presence and degree of alpha clustering within the original nucleus. Observation of multiple alpha particles ( ^4He ) emitted as fragments indicates a stronger clustering effect, and the probability of observing fragments originating from unstable nuclear states increases proportionally with the number of alpha particles detected. This correlation arises because the fragmentation process preferentially excites and breaks apart loosely bound alpha clusters, and higher alpha multiplicity implies a greater contribution from these weakly bound, unstable configurations to the overall nuclear structure. Analysis of fragment yields and energies thus provides quantitative evidence regarding the strength and prevalence of alpha clustering.

Analysis of fragment momentum and angular distribution, conducted through techniques like Angular Correlation and Momentum Measurement, provides detailed insight into the dynamics of nuclear fragmentation. Angular Correlation examines the statistical relationship between the emission angles of multiple fragments, revealing correlations indicative of sequential decay or collective emission. Momentum Measurement, often employing silicon detectors, determines the linear momentum of each fragment, allowing reconstruction of the excitation energy of the fragmented nucleus and identification of resonant states. These measurements are crucial for determining the lifetimes of excited states, testing theoretical models of nuclear structure, and understanding the mechanisms governing the breakup of clustered nuclei; specifically, deviations from isotropic emission patterns suggest non-random fragmentation pathways and provide information about the initial configuration of the nucleus.

Relativistic Collisions: Peering Inside the Nuclear Furnace

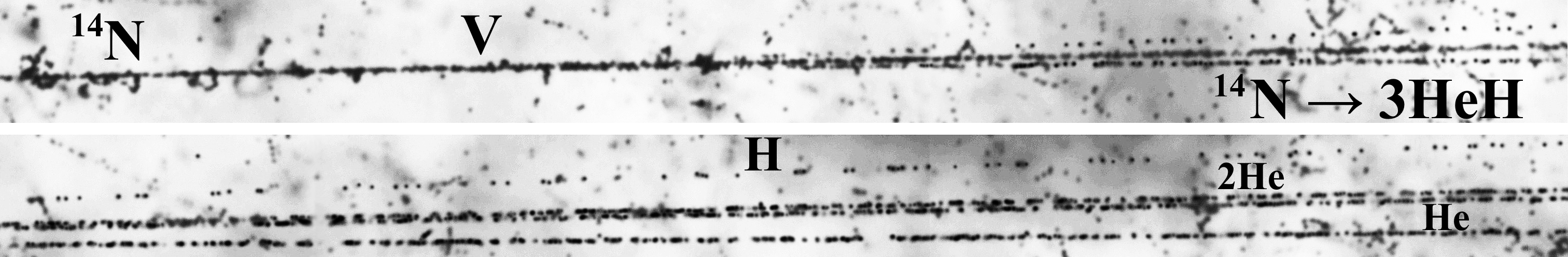

The nuclear emulsion method utilizes a sensitive tracking detector composed of silver halide crystals to record the ionization trails of charged particles produced in relativistic heavy-ion collisions. These collisions induce nuclear dissociation and fragmentation, creating a cascade of secondary particles. By precisely measuring the trajectories of these particles within the emulsion, and combining this data with concurrent beam intensity measurements – which determine the incident flux and interaction rate – researchers can reconstruct the collision kinematics and identify the fragmentation products. The emulsion’s high spatial resolution enables the determination of particle momenta, charge, and velocity, while beam intensity monitoring provides normalization and absolute event rate information essential for quantifying the fragmentation process and extracting cross-sections for specific reaction channels.

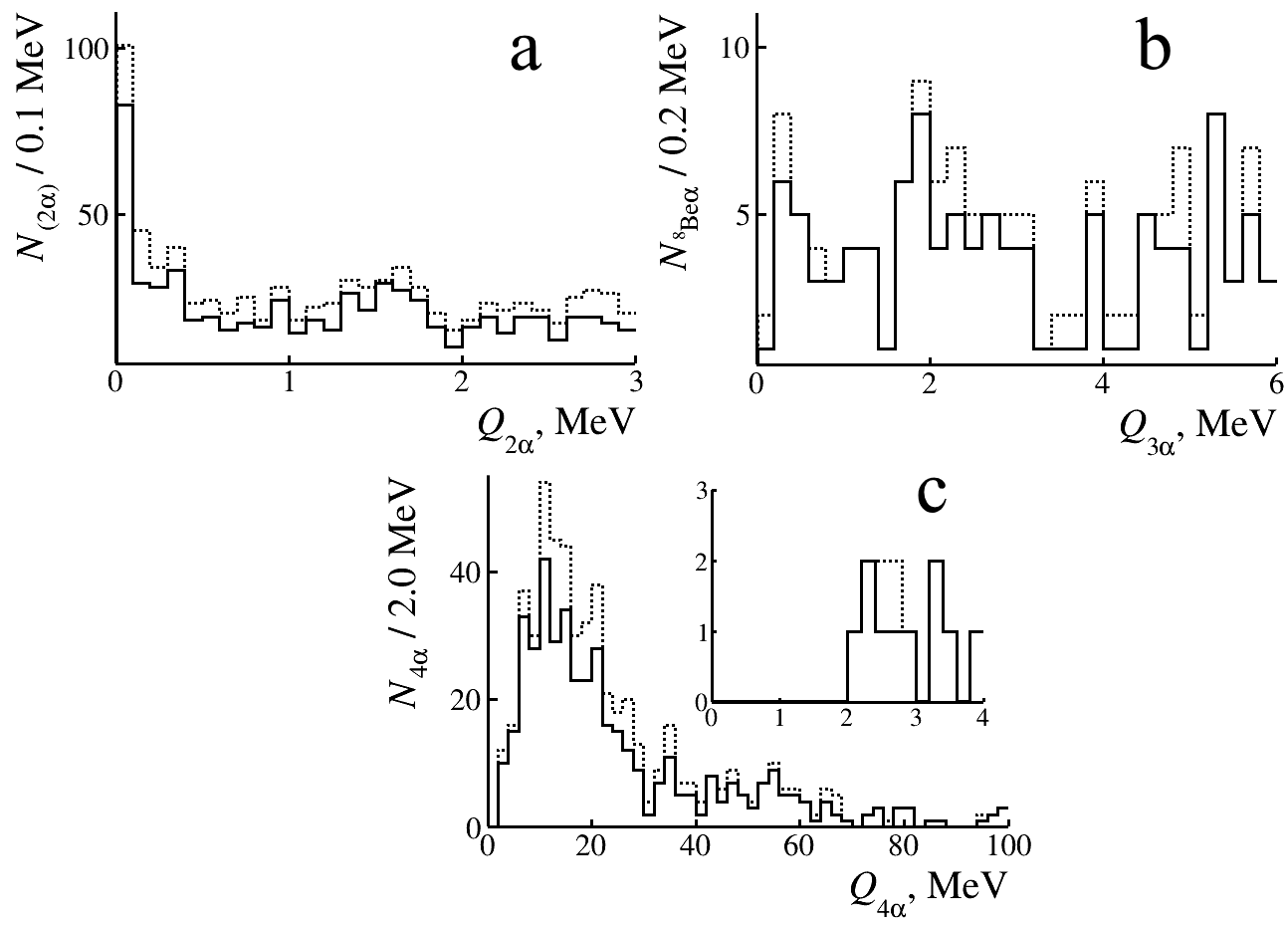

Invariant mass spectroscopy is a key technique in analyzing relativistic fragmentation due to its ability to determine particle masses independent of the reference frame. In high-energy collisions, numerous fragments are produced, and their velocities approach the speed of light, making direct mass determination from momentum and energy measurements impractical due to relativistic effects. By calculating the invariant mass m_{inv} = \sqrt{(E_{total}^2 - (pc)^2)/c^2}, where E_{total} is the total energy, p is the momentum, and c is the speed of light, the combined mass of decay products can be accurately determined. This allows for the unambiguous identification of resonant states and short-lived particles produced in the fragmentation process, even when individual particle momenta are difficult to measure precisely. The technique relies on the principle that the invariant mass is a Lorentz-invariant quantity, meaning it has the same value in all inertial reference frames, providing a consistent and reliable method for fragment identification.

Silicon detectors are employed in relativistic fragmentation studies to provide high-resolution tracking of charged particles emitted during nuclear collisions. These detectors function by measuring the ionization energy deposited by a particle as it traverses the silicon material, allowing for precise determination of particle trajectories and momenta. Unlike nuclear emulsions, which require chemical processing and scanning, silicon detectors offer real-time data acquisition and significantly improved spatial resolution – typically on the order of a few micrometers. This complementary data, particularly regarding particle multiplicity and angular distributions, enhances the accuracy of fragment identification and reconstruction achieved through invariant mass spectroscopy and analysis of data collected by nuclear emulsions. The combination allows for a more complete characterization of the fragmentation process and provides crucial validation of results obtained from each technique.

Reconstruction of relativistic fragmentation relies on the precise measurement of fragment momenta and energies using techniques such as nuclear emulsions, silicon detectors, and invariant mass spectroscopy. By combining data from these methods, the initial colliding nucleus’s characteristics can be determined, and the subsequent decay chain traced. This allows for the determination of fragment types, their four-momenta, and ultimately, the mapping of fragment distributions in phase space. Accuracy is achieved through careful calibration of detector systems and application of kinematic fitting algorithms to minimize uncertainties in fragment reconstruction, enabling detailed studies of the fragmentation process and the properties of nuclear matter under extreme conditions.

The Strong Force at Play: Unlocking Nuclear Secrets

The way in which atomic nuclei break apart, or fragment, isn’t random; it’s a direct consequence of the strong nuclear force-the fundamental interaction that holds protons and neutrons, collectively known as nucleons, together. This force, a residual effect of the even stronger force governing quarks, dictates the energy levels within the nucleus and governs how easily it can be disrupted. When a nucleus becomes unstable and fragments, the resulting pieces and their probabilities of formation are determined by the complex interplay of attractive and repulsive components within the nuclear force. Studying these fragmentation patterns provides a window into the very nature of this force, allowing physicists to map its strength at different distances and refine theoretical models that attempt to describe the behavior of matter at its most fundamental level. These investigations reveal that the nuclear force isn’t merely a simple glue, but a nuanced interaction with surprising consequences for nuclear stability and decay.

The inherent stability of atomic nuclei, and their tendency to break apart, is fundamentally governed by the strong nuclear force. This force, acting between protons and neutrons – collectively known as nucleons – doesn’t simply hold the nucleus together, but also sculpts its structure, favoring certain arrangements like alpha clusters – tightly bound groups of two protons and two neutrons. The precise strength of this force, alongside its short-range nature and spin-dependent characteristics, determines how easily these clusters form and, crucially, how susceptible a nucleus is to fragmentation. A weaker force, or one with altered properties, would result in less stable clusters and a greater likelihood of the nucleus dissociating into its constituent parts. Conversely, a robust force promotes cluster stability and resists fragmentation, highlighting the delicate balance maintained by the nuclear interactions within.

Nuclear fragmentation, the process by which a nucleus breaks apart into smaller constituents, serves as a powerful experimental probe for validating and improving theoretical models of the strong nuclear force. Recent research demonstrates that the rate of this process isn’t fixed, but is acutely sensitive to the extent to which alpha particles cluster together before fusion occurs. Stronger alpha clustering, where these particles briefly form localized, dense groups, dramatically increases the probability of carbon production. This occurs because the clustered configuration effectively enhances the nuclear reaction rate, overcoming the natural repulsive forces between the positively charged nuclei. Consequently, even subtle variations in the strength of alpha clustering can profoundly influence the overall yield of carbon within a star, impacting the elemental composition of stellar remnants and ultimately shaping the building blocks of future stars and planetary systems.

Investigations are increasingly directed toward understanding how unusual arrangements of nuclear matter influence the creation of elements beyond hydrogen and helium. Specifically, research explores the potential role of exotic states, such as the Alpha Particle Bose-Einstein Condensate – a highly ordered collection of alpha particles – as crucial intermediates in nucleosynthesis. These condensates, exhibiting quantum mechanical behavior at the nuclear level, may dramatically alter reaction pathways and enhance the production of heavier elements within stellar environments. The premise is that these condensed states offer a unique pathway for overcoming the Coulomb barrier, effectively increasing reaction rates and influencing the abundance of carbon, oxygen, and beyond. This line of inquiry seeks to bridge the gap between theoretical models of nuclear structure and observed elemental abundances in the universe, potentially reshaping current understandings of stellar evolution and the cosmic origins of matter.

Looking Ahead: Unraveling the Cosmic Recipe

Fragmentation studies, traditionally focused on nuclear physics, are increasingly revealing critical details about the life cycles of stars and the creation of elements. These investigations, which dissect the behavior of nuclei breaking apart under extreme conditions, provide insights into the nuclear reactions powering stellar interiors. The rates at which these reactions occur – such as those forging carbon, oxygen, and heavier elements – are profoundly influenced by the structure of the nuclei involved, a structure directly probed through fragmentation. Consequently, a more refined understanding of fragmentation processes allows scientists to build more accurate models of stellar evolution and nucleosynthesis, predicting the elemental composition of stars and the distribution of elements throughout the universe with greater precision. This has far-reaching implications for interpreting astronomical observations and unraveling the cosmic origins of everything around us.

The creation of carbon within stars, a process vital for life as we know it, hinges significantly on the efficiency of the Triple-Alpha Process – the fusion of three helium nuclei, or alpha particles. Recent research demonstrates that the rate of this process isn’t fixed, but is acutely sensitive to the extent to which alpha particles cluster together before fusion occurs. Stronger alpha clustering, where these particles briefly form localized, dense groups, dramatically increases the probability of carbon production. This occurs because the clustered configuration effectively enhances the nuclear reaction rate, overcoming the natural repulsive forces between the positively charged nuclei. Consequently, even subtle variations in the strength of alpha clustering can profoundly influence the overall yield of carbon within a star, impacting the elemental composition of stellar remnants and ultimately shaping the building blocks of future stars and planetary systems.

Refining computational models of nuclear fragmentation and alpha clustering is poised to significantly improve predictions regarding stellar yields – the amount of each element created within stars – and consequently, the observed abundance of those elements throughout the universe. Recent studies, evidenced by the detection of up to thirteen alpha particles emanating from a single fragmented nucleus, demonstrate the complex interplay of forces governing these events. These observations provide crucial data for validating and calibrating the models, allowing scientists to more accurately simulate the nuclear reactions within stellar cores and supernova explosions. By better understanding how nuclei break down and how alpha particles coalesce, researchers can refine estimates of carbon, oxygen, and heavier element production, ultimately leading to a more complete picture of cosmic chemical evolution and the origins of the elements essential for life.

Investigations are increasingly directed toward understanding how unusual arrangements of nuclear matter influence the creation of elements beyond hydrogen and helium. Specifically, research explores the potential role of exotic states, such as the Alpha Particle Bose-Einstein Condensate – a highly ordered collection of alpha particles – as crucial intermediates in nucleosynthesis. These condensates, exhibiting quantum mechanical behavior at the nuclear level, may dramatically alter reaction pathways and enhance the production of heavier elements within stellar environments. The premise is that these condensed states offer a unique pathway for overcoming the Coulomb barrier, effectively increasing reaction rates and influencing the abundance of carbon, oxygen, and beyond. This line of inquiry seeks to bridge the gap between theoretical models of nuclear structure and observed elemental abundances in the universe, potentially reshaping current understandings of stellar evolution and the cosmic origins of matter.

The pursuit of elegant theoretical models, as demonstrated by this study of relativistic dissociation and alpha clustering, invariably encounters the stubborn realities of production. Researchers meticulously dissecting the $^{8}$Be nucleus and the Hoyle state believe they are mapping fundamental structures, yet any observed stability is merely a temporary reprieve. As Simone de Beauvoir observed, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Similarly, these nuclear states aren’t inherent; they become momentarily defined through observation, before decaying into something else. Documentation of these fleeting configurations, however detailed, remains a collective self-delusion, a snapshot of a system destined to break down. If a bug-or in this case, a nuclear instability-is reproducible, it simply confirms the system’s inherent limitations, not its elegance.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The pursuit of alpha clustering, as evidenced by this work with relativistic nuclei and nuclear emulsions, reveals a persistent truth: every elegant resonance discovered will eventually demand explanation for its imperfections. The Hoyle state in $^{8}$Be, once a neat solution to carbon production, now necessitates increasingly refined models to account for observed decay pathways and, inevitably, the unexpected. The identification of potential alpha-particle Bose-Einstein condensates, while intriguing, highlights the field’s continuing struggle to differentiate genuine collective effects from the artifacts of complex many-body interactions.

Future iterations will undoubtedly focus on higher-statistics data, pushing the limits of emulsion techniques-or perhaps abandoning them for more automated detection methods. But increased precision only delays the inevitable confrontation with the underlying reality: architecture isn’t a diagram, it’s a compromise that survived deployment. The search for exotic resonances, while valuable, must also acknowledge that everything optimized will one day be optimized back, and the quest for ‘clean’ alpha clustering will likely yield ever-more-complex configurations.

The challenge, then, isn’t simply to map the nuclear landscape with greater accuracy. It’s to accept that the ‘true’ structure of these systems may be fundamentally resistant to simple description. This work, and the field it represents, doesn’t build theories-it resuscitates hope, one carefully measured decay at a time.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21425.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- Battlefield 6 Season 2 Update Is Live, Here Are the Full Patch Notes

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- Dan Da Dan Chapter 226 Release Date & Where to Read

- Ashes of Creation Mage Guide for Beginners

- Duffer Brothers Discuss ‘Stranger Things’ Season 1 Vecna Theory

- ‘Crime 101’ Ending, Explained

- Gwyneth Paltrow’s Son Moses Martin Makes Red Carpet Debut

2026-02-01 19:49