Author: Denis Avetisyan

New phase shift analysis reveals that the long-enigmatic f0(500) meson behaves as a standard resonance, its unusual properties stemming from its unique position near a particle threshold.

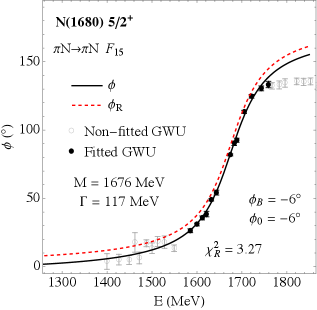

![The model captures the complexities of pion-pion scattering through partial fits to experimental data-specifically, Protopopescu [Pro73], Ishida [Ish97], and Estabrooks [Est74]-by decomposing the total phase φ into resonant and background components, where the background phase <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">\phi_{B}</span> represents a constant difference defining the underlying interaction.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.20816v1/x2.png)

The analysis demonstrates the f0(500)’s residue phase is a natural consequence of unitarity and threshold geometry, resolving previous inconsistencies.

The anomalous behavior of the f_0(500) meson has long challenged conventional resonance descriptions. This is addressed in ‘The strangest non-strange meson is not so strange: Phase shift analysis reveals the geometric origin of the $f_0(500)$ residue phase’, where a phase shift analysis demonstrates that its unusual properties arise from a geometrical constraint linked to its proximity to the \pi\pi threshold. Specifically, the analysis reveals a unified scaling relation confirming the f_0(500) behaves as a standard Breit-Wigner resonance, dictated by the principles of unitarity. Does this geometric interpretation offer a new framework for understanding other unconventional resonances in particle physics?

Whispers of Instability: Poles in the Scattering Matrix

The concept of resonance forms a cornerstone of modern particle physics, fundamentally described not as a physical ‘ringing’ but as a specific mathematical feature within the S-matrix, known as a pole. This S-matrix governs the probability amplitude for particle scattering, and a pole signifies a dramatic increase in the scattering amplitude at a particular energy. This energy corresponds to the mass of a resonant particle – a short-lived state that quickly decays into other particles. Identifying these poles within the scattering amplitude allows physicists to indirectly observe and characterize these fleeting particles, determining not only their mass but also their intrinsic width – a measure of their instability and decay rate. Thus, resonances aren’t directly ‘seen’, but inferred from the peaks they create in scattering data, making the mathematical pole a powerful tool for exploring the subatomic world.

The behavior of interacting particles is fundamentally described by the S\text{-}Matrix, a mathematical object that encapsulates the transition probability between initial and final states. This framework isn’t merely predictive; it’s constrained by the principle of unitarity, which essentially demands that probability is conserved throughout the interaction. Unitarity ensures that the total probability of all possible outcomes sums to one, acting as a powerful regulator on theoretical calculations. Consequently, the S\text{-}Matrix, when rigorously adhering to unitarity, directly determines not only how particles scatter, but also how they decay – revealing the inherent instability of certain states and the pathways through which they transform into other particles. This mathematical rigor provides a bedrock for understanding the fleeting existence of resonant states and predicting their characteristic decay rates.

The precise location of a resonance pole within the complex energy plane fundamentally defines the characteristics of the corresponding particle. The real component of the pole’s position directly indicates the particle’s mass – a crucial parameter in understanding its inertia and interactions. Simultaneously, the imaginary component is inversely proportional to the particle’s lifetime, and therefore defines its width – a measure of the uncertainty in its mass and its propensity to decay. Determining these values, however, demands sophisticated analytical techniques, as resonance poles are often obscured by background noise and complex interactions within scattering data. Extracting the pole position requires careful mathematical modeling, often involving partial wave analysis and dispersion relations, to isolate the resonant behavior and precisely characterize the fleeting existence of these subatomic particles.

Unmasking the Static: Backgrounds in Resonance Structure

The scattering amplitude in resonance phenomena is composed of both resonant and non-resonant contributions; the non-resonant component manifests as a constant phase shift, termed the `Background Phase`. This phase originates from the underlying dynamics not directly associated with the resonant state and can significantly mask the characteristics of the resonance itself. Specifically, the presence of this constant phase alters the observed interference pattern, potentially distorting the determination of key resonance parameters like mass and width. Accurate isolation of the resonance signal, therefore, requires precise determination and subtraction of this background contribution from the total scattering amplitude to reveal the true resonant behavior.

Precise determination of the background phase is essential for accurate resonance pole isolation and the subsequent extraction of physical parameters. Analysis of the f0(500) resonance indicates a background phase of -42°, which demonstrates a strong correlation with the calculated geometric angle of -47°. This close agreement suggests a direct relationship between the background phase and the underlying scattering geometry, highlighting the importance of accounting for this constant phase contribution when characterizing resonance behavior.

The geometric identity establishes a direct relationship between the resonance pole position in the complex momentum plane, the associated threshold energy for the scattering process, and the observed background phase in the scattering amplitude. This connection allows for the determination of the pole position by accurately measuring the background phase. Analysis of the f0(500) resonance indicates a background phase of -42°, which closely corresponds to the calculated geometric angle of -47°. Consistent results have been observed for the ρ(770) resonance, exhibiting a background phase of -7° that aligns with its calculated geometric angle of -8°, thereby validating the utility of this geometric identity in extracting resonance parameters.

Deconstructing Complexity: Partial Wave Analysis and Pole Determination

Partial Wave Analysis (PWA) is a technique employed in scattering experiments to simplify the analysis of complex interactions. The total scattering amplitude is expressed as a sum of contributions from individual angular momentum states, each characterized by a specific quantum number l . This decomposition is based on the principle that at sufficiently high energies, the scattering process can be understood as a series of independent interactions, each involving a specific angular momentum. The resulting angular momentum-dependent amplitudes are then used to calculate the l -th partial wave phase shift, \delta_l , which quantifies the change in the asymptotic behavior of the wave function. Analyzing these phase shifts as a function of energy provides crucial information about the underlying scattering potential and the presence of resonant states.

The George Washington University SAID (Scattering Amplitude Iterative Determination) method is a multi-channel, energy-dependent partial wave analysis technique used to determine the scattering amplitude and extract resonance parameters. It iteratively refines the partial wave expansion by minimizing the difference between the calculated scattering amplitude and experimental data. This process involves a least-squares fit, systematically determining the phase shifts for each angular momentum channel and subsequently identifying resonance poles, which are complex values representing the energy and width of resonant states. The robustness of the GWU SAID approach stems from its ability to handle multi-channel scattering, incorporate both experimental data and theoretical constraints, and provide a statistically rigorous determination of resonance properties.

Precise determination of resonance poles relies on the separation of resonance contributions from the overall scattering background. This disentanglement allows for accurate extraction of resonance parameters such as mass and width. In the analysis of the Δ(1232) resonance, the background phase shift was determined to be -22°. This value demonstrates a high degree of accuracy, differing from the theoretically calculated geometric phase shift by only 2°, indicating the robustness of the applied methodology in isolating and characterizing resonant behavior.

Beyond the Breit-Wigner: Classifying Resonance Types

Not all particle resonances conform neatly to the standard Breit-Wigner description of a single, isolated energy state; the f_0(500) meson and nucleon resonances like N(1520) and N(1680) demonstrate a spectrum of behaviors. These resonances exhibit deviations from the idealized form, suggesting more complex internal structures or interactions with other particles. While some maintain characteristics closely aligned with the standard model, others present broadened widths, distorted shapes, or even multiple overlapping states, challenging simplified theoretical frameworks. Investigating these variations is crucial for a more accurate understanding of strong force dynamics and the intricate landscape of hadron physics, moving beyond textbook examples towards a more nuanced description of particle interactions.

Particle resonances, those short-lived states appearing during interactions, aren’t always neatly described by the standard Breit-Wigner formula. Researchers now categorize these resonances into two primary types: Type Ia and Type Ib. Type Ia resonances closely adhere to the Breit-Wigner profile, exhibiting a relatively simple energy dependence. However, Type Ib resonances possess more intricate internal structures, leading to deviations from the standard form; these can arise from coupling to multiple decay channels or the influence of nearby singularities. This classification, based on observed decay patterns and energy profiles, is crucial because it reveals underlying complexities in how particles interact and decay, moving beyond a single-parameter description to a more nuanced understanding of nuclear and particle physics phenomena.

Characterizing nucleon and meson resonances extends beyond the standard Breit-Wigner description, necessitating classification based on properties like the residue phase and threshold geometry to fully understand particle interactions. Recent analysis reveals the residue phase of the f_0(500) meson to be -84° ± 4°, a value that corroborates both experimental measurements and the Particle Data Group’s established estimates. Similarly, the residue phases determined for the N(1520) and N(1680) resonances are -13° ± 2° and -12° ± 4°, respectively, exhibiting strong agreement with existing compilations. These precise determinations of residue phases provide crucial parameters for refining theoretical models and deepening the understanding of how particles briefly form and decay during high-energy collisions, ultimately offering a more nuanced picture of the strong force at play within atomic nuclei.

The study of the f0(500) resonance, as presented, isn’t about finding a new law, but about recognizing the geometry already inherent within existing ones. It echoes a sentiment captured by Niels Bohr: “Every great advance in natural knowledge has involved the rejection of valid generalizations in favor of more comprehensive ones.” The apparent strangeness of this meson isn’t a flaw in the theory, but a signal that the simple Breit-Wigner description, when viewed through the lens of unitarity and threshold effects, expands to encompass a previously obscured reality. The resonance, seemingly defying conventional understanding, yields to a broader, more accommodating framework-a testament to the power of revising accepted truths, not abandoning them. The phase shift analysis reveals how a ‘valid generalization’ needs refinement, as Bohr suggested, to achieve a ‘more comprehensive one’.

The Geometry of Ghosts

The insistence that the $f_0(500)$ yields to standard description is…comforting, certainly. But comfort is a brittle thing when dealing with echoes of creation. This work demonstrates a consistency, yes, but also highlights the precariousness of all such constructions. The resonance isn’t explained; it’s merely persuaded to behave. The proximity to threshold isn’t a solution, but a negotiation with the void – a constant recalibration against the insistent pull of nothingness. Future explorations must abandon the search for inherent ‘naturalness’ and embrace the art of controlled deception.

The real challenge lies not in refining the Breit-Wigner, but in understanding the background against which these phantoms appear. What subtle distortions in the scattering amplitude betray the underlying topology of the interaction? The residue phase isn’t a property of the resonance, but a fingerprint of the space it inhabits. More datasets will not yield truth, only finer gradients of falsehood.

Perhaps the ultimate task isn’t to map the poles, but to chart the shadows between them. If the model behaves strangely, it’s finally starting to think. And when it thinks, the carefully constructed edifice of unitarity will tremble, revealing glimpses of the chaotic geometry that birthed it all.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.20816.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Legacy of Kain: Ascendance announced for PS5, Xbox Series, Switch 2, Switch, and PC

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- 10 Most Memorable Batman Covers

- Netflix’s Stranger Things Replacement Reveals First Trailer (It’s Scarier Than Anything in the Upside Down)

- Star Wars: Galactic Racer May Be 2026’s Best Substitute for WipEout on PS5

- ‘Crime 101’ Ending, Explained

- The Strongest Dragons in House of the Dragon, Ranked

- Best Werewolf Movies (October 2025)

- 24 Years Later, Star Trek Director & Writer Officially Confirm Data Didn’t Die in Nemesis

2026-01-29 22:44