Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study uses quantum oscillations to map the unique spin-split Fermi surface of the altermagnetic material CrSb.

Quantum oscillation measurements confirm a complete experimental picture of CrSb’s altermagnetic Fermi surface and reveal details about its effective mass and Berry phase.

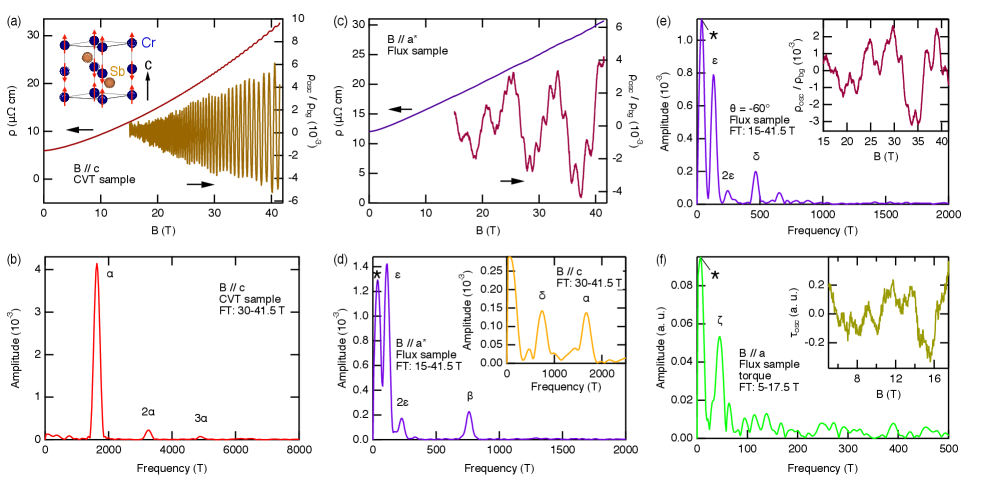

Establishing a definitive link between predicted band structures and experimentally observed electronic properties remains a central challenge in the study of novel magnetic materials. Here, we present a comprehensive quantum oscillation investigation of CrSb, as detailed in ‘Altermagnetic spin-split Fermi surfaces in CrSb revealed by quantum oscillation measurements’, which successfully identifies multiple Fermi surface sheets arising from four spin-non-degenerate bands. These findings provide robust, bulk-sensitive confirmation of the altermagnetic spin-split Fermi surface in CrSb, yielding a complete picture of its electronic behavior. Will this detailed understanding of CrSb’s electronic structure pave the way for realizing its potential in spintronic devices and beyond?

Beyond Conventional Magnetism: Uncovering Hidden Orders

Conventional magnets owe their properties to the collective alignment of electron spins, creating a macroscopic magnetic moment. However, antiferromagnets challenge this simplicity by arranging spins in an opposing, or antiparallel, fashion. This doesn’t result in a net magnetization, but instead gives rise to a unique internal order with intriguing consequences; neighboring spins cancel each other out, but the overall structure remains magnetically ordered. While seemingly counterintuitive, this arrangement offers several advantages-antiferromagnetic materials are generally more robust against external magnetic fields and can exhibit faster switching speeds than traditional ferromagnets. This inherent stability and potential for dynamic control make antiferromagnets promising candidates for next-generation data storage and spintronic devices, offering a pathway beyond the limitations of conventional magnetic technologies.

Altermagnetism represents a departure from conventional magnetic order, arising as a distinct form of antiferromagnetism where the behavior of electrons is unexpectedly momentum-dependent. Unlike typical antiferromagnets with alternating spin alignment, altermagnetic materials exhibit a spin splitting that varies according to an electron’s momentum-essentially, how fast and in what direction it’s moving. This unique characteristic stems from a specific crystallographic symmetry and leads to a non-zero net spin polarization when observed from certain momentum states, a phenomenon not seen in standard antiferromagnets. The implications of this momentum-dependent splitting are significant, potentially enabling the creation of novel spintronic devices where information is carried by electron spin, and opening new avenues for manipulating and controlling quantum materials with unprecedented precision.

The pursuit of subtle magnetic orders, such as altermagnetism, represents a critical frontier in materials science with far-reaching implications for technological advancement. These non-conventional arrangements of electron spins aren’t simply academic curiosities; they unlock the potential for entirely new classes of quantum materials exhibiting exotic properties. Crucially, the momentum-dependent spin splitting observed in altermagnets-and other similar systems-offers a pathway to manipulate spin currents with unprecedented control. This capability is essential for the development of next-generation spintronic devices, promising faster, more energy-efficient electronics, and potentially enabling breakthroughs in quantum computing and data storage. The ability to finely tune and harness these magnetic textures, therefore, is not merely a scientific challenge, but a vital step towards realizing transformative technologies.

Mapping Electronic Landscapes: The Power of Quantum Oscillations

Quantum oscillation measurements, including the de Haas-van Alphen (dHvA) effect and the Shubnikov-de Haas (SdH) oscillation, provide a direct method for determining the shape and size of a material’s Fermi surface. The dHvA effect observes oscillations in magnetic susceptibility as a function of magnetic field strength, while SdH oscillation measures oscillations in resistivity. Both phenomena arise from the quantization of electron orbits in momentum space under the influence of a strong applied magnetic field B. The frequency of these oscillations is directly proportional to the extremal cross-sectional area of the Fermi surface perpendicular to the magnetic field direction. By systematically varying the magnetic field orientation and analyzing the oscillation frequencies, a detailed map of the Fermi surface can be constructed, revealing information about the electronic band structure and carrier concentrations.

Quantum oscillation measurements, such as the de Haas-van Alphen effect and Shubnikov-de Haas oscillation, function by monitoring changes in material properties-including magnetic susceptibility, electrical resistance, and specific heat-when subjected to high magnetic fields. The application of a strong magnetic field quantizes the continuous energy spectrum of electrons into discrete Landau levels. As the magnetic field is varied, these Landau levels sweep through the Fermi surface, causing oscillations in the measured physical property. The frequency of these oscillations is directly related to the cross-sectional area of the Fermi surface perpendicular to the magnetic field direction, while the amplitude provides information about the density of states at the Fermi level. These oscillations are observed because only electrons near the Fermi surface contribute significantly to the measured signal due to their ability to scatter and respond to changes in the magnetic field.

Analysis of quantum oscillation data allows for the precise determination of material properties related to electron behavior. Specifically, the frequency of observed oscillations is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the Fermi surface perpendicular to the applied magnetic field. From these frequencies, the effective mass of charge carriers can be calculated, providing insight into how strongly electrons respond to external forces within the material. For example, measurements on band-3 have established an effective mass of 0.29 times the free electron mass m_0 . Furthermore, the temperature and field dependence of oscillation amplitudes can reveal the presence and characteristics of spin splitting patterns, such as Zeeman splitting, which provides information about the material’s magnetic properties and band structure.

CrSb: A Model System for Altermagnetism

Single crystals of chromium antimonide (CrSb) were synthesized utilizing the Sn-Flux method, a technique involving the dissolution of CrSb precursors into a tin solvent followed by controlled cooling to induce crystallization. This process yielded samples suitable for detailed characterization; specifically, crystals exhibiting dimensions sufficient for quantum oscillation measurements and possessing minimal observable impurities as determined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. The Sn-Flux method proved effective in overcoming the challenges associated with CrSb’s high melting point and stoichiometric control, resulting in high-quality single crystals crucial for validating the material’s altermagnetic properties and probing its electronic band structure.

Quantum oscillation measurements performed on CrSb single crystals provide direct confirmation of altermagnetic ordering and characterize the resulting Fermi surface topology. These measurements, specifically utilizing the de Haas-van Alphen effect, detected distinct oscillation frequencies corresponding to extremal cross-sectional areas of the Fermi surface. Analysis of these frequencies and their angular dependence revealed a Fermi surface significantly modified by the alternating spin structure inherent to the altermagnetic state, differing substantially from the Fermi surface expected for conventional ferromagnetic or paramagnetic materials. The observed topology indicates a complex interplay between band structure and spin ordering in CrSb, confirming its suitability as a model system for studying altermagnetism.

Quantum oscillation measurements on CrSb provided direct evidence of momentum-dependent spin splitting, a key characteristic of altermagnetic materials. Analysis of these oscillations yielded effective masses for electrons within two distinct bands: band-1 exhibited an effective mass of 1.2 m_0, while band-2 demonstrated a slightly higher value of 1.23 m_0. These measured effective masses confirm the band structure calculations predicting the differing responses of each band to the altermagnetic ordering, and provide quantitative data supporting the observed spin splitting as a function of momentum.

The Limits of Observation: Not All Splits Are Equal

While materials such as manganese telluride (MnTe) demonstrably exhibit spin splitting – a crucial characteristic for potential altermagnetic behavior – their complex electronic band structures often obscure the observation of clear quantum oscillations. This phenomenon arises because the specific arrangement of energy levels within MnTe doesn’t allow for the formation of a well-defined Fermi surface, a prerequisite for the coherent transport of electrons needed to generate measurable oscillations. Essentially, the spin-split electrons are scattered and disrupted within the material’s band structure, effectively masking the subtle quantum signals that would otherwise confirm the presence of altermagnetism. This limitation underscores the importance of carefully considering a material’s band topology alongside its spin properties when searching for novel magnetic phases.

The efficacy of quantum oscillation techniques, used to probe the electronic properties of materials, fundamentally relies on the existence of a well-defined Fermi surface. This surface, representing the boundary between occupied and unoccupied electronic states in momentum space, must be continuous and clearly delineated for these oscillations to manifest as measurable signals. Materials lacking such a surface, even if possessing intriguing magnetic properties like spin splitting, will obscure the quantum signatures, rendering traditional analysis ineffective. The presence of a sharp Fermi surface allows electrons to respond coherently to external magnetic fields, creating the periodic variations in measurable quantities – a condition absent in systems with diffuse or poorly defined boundaries between electronic states. Consequently, researchers prioritize materials exhibiting a clear Fermi surface when seeking to uncover novel quantum phenomena and accurately characterize their electronic behavior.

Recognizing the inherent limitations of quantum oscillation techniques in materials like MnTe is not a setback, but rather a crucial step towards identifying genuine altermagnets. The absence of a well-defined Fermi surface in certain compounds necessitates a recalibration of research efforts, shifting focus towards materials possessing the requisite electronic structure for successful observation of these oscillations. This realization also spurs the development of complementary characterization strategies – techniques beyond quantum oscillations – to probe the magnetic properties and confirm the existence of altermagnetism through alternative means. By acknowledging these challenges, scientists can strategically refine their material selection, enhance experimental protocols, and ultimately accelerate the discovery and validation of this novel magnetic state.

Unveiling the Spin Texture: GG- and DD-Wave Symmetries

Quantum oscillation data, subjected to rigorous analysis, unveiled distinct patterns in spin splitting within the altermagnetic material, leading to the categorization of these patterns as GG-wave and DD-wave symmetries. These symmetries aren’t merely descriptive; they represent fundamental characteristics of how spin is organized in momentum space, dictating the material’s response to external stimuli. The GG-wave symmetry indicates a spin texture where the spin direction rotates in a specific way along one momentum direction, while the DD-wave symmetry presents a more complex, two-dimensional rotation. Identifying these symmetries is paramount as they directly influence the material’s electronic properties and, crucially, its potential for manipulating spin-based information – a cornerstone of advanced spintronic devices.

The spin texture within this altermagnetic material isn’t simply a static orientation of electron spins, but rather a complex, momentum-dependent landscape. This means the direction of an electron’s spin is intrinsically linked to its motion through the crystal, exhibiting different arrangements for electrons traveling in various directions. GG-wave and DD-wave symmetries specifically categorize these arrangements, describing how the spin rotates or aligns relative to the electron’s momentum. These symmetries aren’t merely geometrical curiosities; they dictate the material’s response to external stimuli and influence crucial properties like electron scattering, which, in this material, occurs over timescales ranging from 0.11 to 0.38 picoseconds. Understanding this momentum dependence is therefore paramount, as it unlocks the potential to engineer materials with tailored spin-related functionalities for advanced spintronic devices.

The identification of GG- and DD-wave symmetries within altermagnetic materials holds significant implications for both fundamental physics and applied spintronics. These symmetries dictate how electron spin is textured in momentum space, influencing electron behavior and opening possibilities for manipulating spin currents. Crucially, this spin texture can give rise to the Berry Phase, a geometric effect that allows for the control of electron transport without the need for external magnetic fields. Measurements indicate electron scattering times within the material range from 0.11 to 0.38 picoseconds, suggesting a viable timeframe for harnessing these quantum effects in novel devices. Further research into these symmetries could thus unlock pathways for low-energy, high-efficiency spintronic technologies, capitalizing on the inherent quantum properties of the material.

The study of CrSb’s altermagnetic properties reveals a fascinating interplay between material structure and emergent electronic behavior. This isn’t simply a matter of mapping Fermi surfaces; it’s about deciphering how spin configurations dictate conductive pathways. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau observed, “The body is but the instrument of the soul,” and in this case, the crystalline lattice of CrSb is the instrument through which its unique spin-splitting manifests. Every deviation from a classically rational metallic behavior – the complex Fermi surface topology revealed by quantum oscillation – is a window into the underlying physics governing this altermagnetic state. The effective mass calculations, alongside the Berry phase analysis, demonstrate that understanding the material requires recognizing the inherent complexities beyond simple models.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The detailed mapping of CrSb’s altermagnetic Fermi surface, achieved through quantum oscillation, feels less like a culmination and more like a sharpening of the questions. The study confirms a band structure subtly, yet profoundly, different from conventional ferromagnets – a difference driven not by a desire for magnetic order, but by a peculiar symmetry breaking. It’s a reminder that materials don’t simply have properties; they evade them, settling into states of minimal resistance, mirroring the compromises inherent in any complex system.

The success of DFT+UU in describing the electronic structure is, predictably, a double-edged sword. It provides a functional description, but obscures the underlying reasons why this particular functional is necessary. Future work will likely focus on refining these density functional approximations, though it’s reasonable to suspect this is an exercise in damage control – attempting to force a framework built for simpler systems to accommodate a reality it wasn’t designed for. The true challenge lies in models that embrace complexity, not attempt to smooth it over.

Ultimately, the interest in altermagnetism isn’t purely about finding new materials with exotic electronic properties. It’s about the search for order in a universe that seems to prefer ambiguity. These materials force a reckoning with the limitations of existing theoretical frameworks, and reveal that the pursuit of understanding isn’t about finding the answer, but about continually refining the questions.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.19105.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Sunday Rose Kidman Urban Describes Mom Nicole Kidman In Rare Interview

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- All 6 Takopi’s Original Sin Episodes, Ranked

- 10 Best Pokemon Movies, Ranked

2026-01-28 19:47