Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new Bayesian framework leveraging Gaussian Processes is helping astronomers dissect the fluctuating light from quasars to refine our understanding of the universe’s expansion.

This review details a flexible approach to analyzing non-stationary quasar light curves for improved cosmological time delay measurements and Bayesian inference.

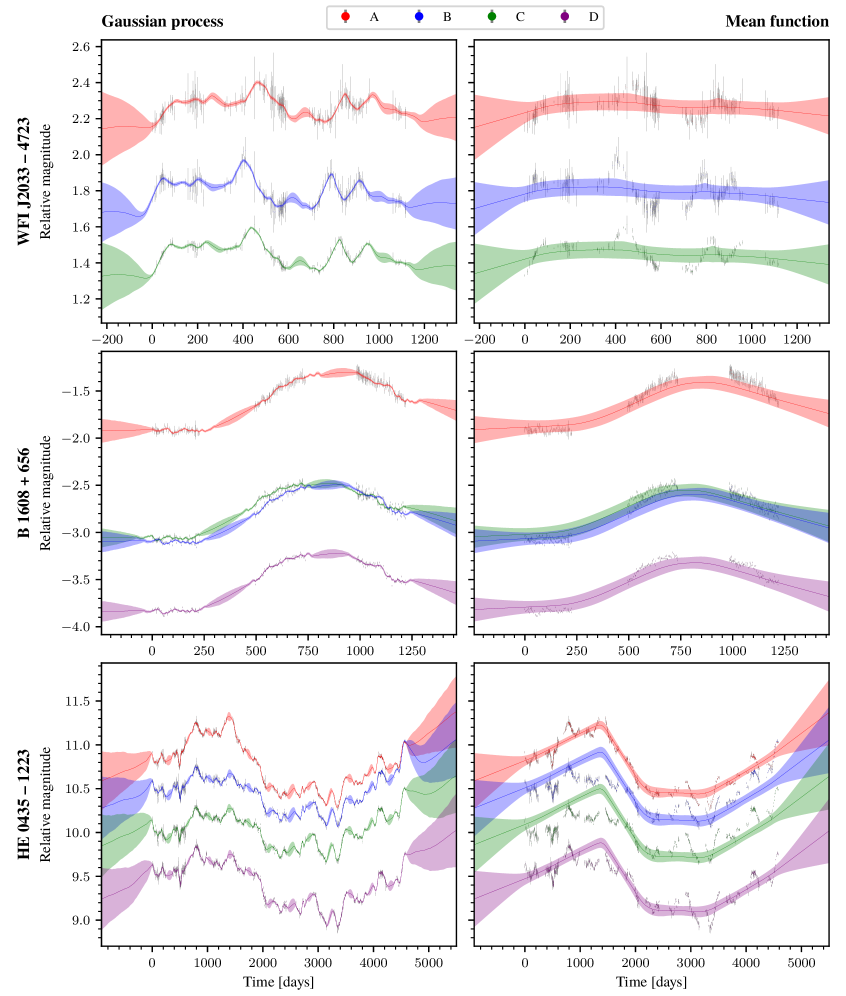

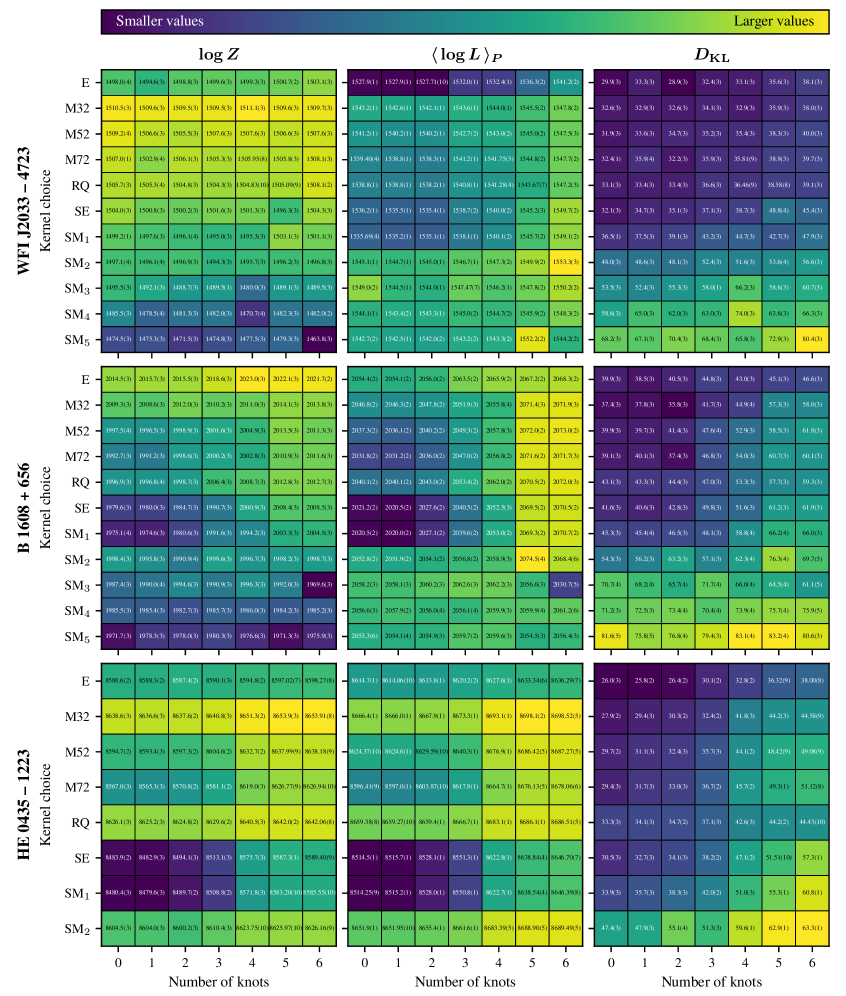

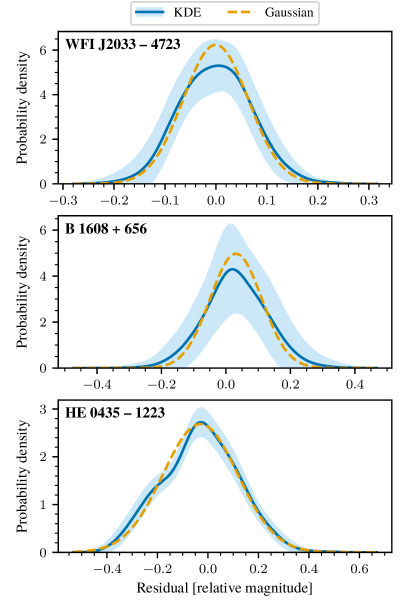

Establishing robust cosmological measurements from quasar time delays requires careful modeling of intrinsic light curve variability. This is addressed in ‘Time delays and stationarity in quasar light curves’, which presents a fully Bayesian framework employing Gaussian processes to disentangle deterministic, non-stationary drifts from stationary stochastic processes in quasar light curves. The analysis of three quasars reveals evidence for non-stationarity in some sources and identifies preferred kernel functions describing their variability, while also mitigating biases in time delay estimation via a refined nested sampling protocol. Will this approach unlock more precise measurements of the Hubble constant and further constrain cosmological models?

The Alluring Variability of Distant Beacons

Quasars, among the brightest objects in the universe, aren’t static beacons but rather exhibit dramatic fluctuations in brightness over various timescales. This complex variability, captured in what are known as quasar light curves, isn’t merely a fascinating characteristic; it’s a powerful tool for probing the environments surrounding supermassive black holes. The patterns of these brightness changes offer clues about the accretion disk – the swirling mass of gas and dust falling into the black hole – and the broad-line region, where energetic photons interact with gas clouds. By meticulously analyzing these light curves, astronomers can indirectly map the size, density, and dynamics of these regions, providing crucial insights into how galaxies themselves evolve and grow over cosmic time. Furthermore, the precise measurement of quasar variability can be used to refine cosmological models and even test fundamental physics, making it a cornerstone of modern astrophysical research.

Analyzing the fluctuating light of quasars – incredibly distant and luminous galactic nuclei – presents a significant analytical challenge due to the irregular nature of astronomical observations. Conventional time series techniques, such as those based on Fourier analysis, assume evenly spaced data points to accurately decompose a signal into its constituent frequencies; however, quasar monitoring campaigns are often hampered by gaps in coverage resulting from weather conditions, telescope scheduling, and detector limitations. This uneven sampling introduces artifacts and biases into the analysis, potentially masking or misinterpreting genuine variations in the quasar’s emission. Consequently, applying standard Fourier methods directly can lead to inaccurate estimations of characteristic timescales and amplitudes of variability, hindering efforts to understand the physical processes occurring within these active galactic nuclei and their impact on surrounding cosmology.

Quasar time series are notoriously difficult to analyze because their statistical properties – things like average brightness and the patterns of fluctuations – change over time, a characteristic known as non-stationarity. This presents a significant challenge to traditional analytical techniques, which often assume consistent behavior. Successfully modeling this non-stationarity is not merely a technical refinement, but a crucial step towards unlocking the physical processes at play within quasars and their host galaxies. Researchers are developing advanced statistical frameworks, including methods capable of adapting to evolving patterns and separating genuine physical signals from observational noise, to effectively dissect these complex light curves. These robust methods promise to reveal insights into the accretion disks surrounding supermassive black holes, the dynamics of gas flows, and even the geometry of the emitting regions – ultimately refining cosmological measurements dependent on quasar behavior.

A New Framework for Mapping Complexity

Gaussian Processes (GPs) represent a non-parametric Bayesian approach to time series modeling, differing from traditional parametric methods which assume a fixed functional form. Instead of estimating a limited set of parameters, GPs define a probability distribution over functions directly. This is achieved by defining a mean function and a covariance function – the kernel – which characterize the expected value and variability of the time series. Crucially, GPs naturally accommodate irregular time intervals between observations without requiring interpolation or resampling, a significant advantage over methods reliant on evenly spaced data. The predictive distribution at any given time point is also a Gaussian distribution, facilitating uncertainty quantification. This probabilistic framework allows for robust modeling and forecasting, especially when data is sparse or noisy.

Gaussian Processes utilize kernel functions to define the covariance between data points, effectively capturing correlations and enabling modeling of complex variability. The Matérn Kernel, parameterized by a smoothness parameter ν, provides control over function smoothness, while the Spectral Mixture (SM) Kernel combines multiple periodic functions with varying frequencies and amplitudes. These kernels allow GPs to represent a wide range of functions without explicitly defining a parametric model; the kernel’s parameters are learned directly from the data. The choice of kernel significantly impacts the GP’s ability to model specific data characteristics, with SM Kernels often performing well on non-stationary data due to their flexibility in capturing localized patterns.

Flexknot introduces a flexible mean function component to Gaussian Process (GP) modeling, addressing limitations of traditional GP approaches which often assume a constant or linear mean. This is achieved through the use of basis functions and knot points, allowing the mean function to adapt to non-linear trends and complex patterns within the observed time series data. The placement of these knot points, and the associated weights, are optimized during the GP training process, effectively learning the underlying mean structure of the data. This adaptability is particularly beneficial for time series exhibiting seasonality, trends, or other non-stationary characteristics, leading to improved predictive accuracy compared to GPs with simpler mean functions. The resulting mean function is a weighted sum of basis functions centered around the knot points, providing a versatile representation of the underlying data trend.

Unveiling the Mechanisms of Variability

The Damped Random Walk (DRW) model posits that quasar light curves exhibit variability resulting from a series of random, uncorrelated events with a characteristic timescale for decay. This timescale, often denoted as τ, dictates how long fluctuations in luminosity persist before diminishing. Applying the DRW model to observed quasar light curves requires fitting the data to a power spectrum, where the power is proportional to 1/f^2 at low frequencies and decreases at higher frequencies due to the damping effect. Successful fits demonstrate that the DRW model can reproduce observed structure functions and power spectra, suggesting that a significant portion of quasar variability arises from stochastic processes with a relatively long characteristic timescale, potentially linked to processes within the accretion disk.

Reverberation Mapping (RM) is a technique used to determine the size and geometry of the Broad Line Region (BLR) in Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN). This method relies on the observation of time delays between variations in continuum emission from the accretion disk and the corresponding changes in the broad emission lines. Variations in the continuum originate from closer regions of the disk, while broad emission lines are produced by gas clouds orbiting the supermassive black hole at larger distances. By measuring the time it takes for a change in continuum flux to propagate to the emission line region – typically days to months – and knowing the velocity of the emitting gas (v), the size of the BLR can be estimated using the relation R = v \Delta t. These size estimates, combined with luminosity measurements, provide constraints on the density and geometry of the BLR gas, and indirectly, on the accretion rate and mass of the central supermassive black hole.

Computational modeling of quasar phenomena, including light curve variability and the dynamics of the broad-line region, provides a crucial framework for testing theoretical predictions against observational data. By simulating these processes, researchers can compare model outputs – such as time delays measured via Reverberation Mapping or the statistical properties of light curves generated by the Damped Random Walk – with observed characteristics. Discrepancies between model predictions and observations then necessitate refinement of the underlying physical assumptions – for example, adjustments to accretion disk geometry, black hole spin parameters, or the nature of the variability driving mechanisms – leading to a more accurate and nuanced understanding of quasar physics. This iterative process of modeling, comparison, and refinement is essential for progressing beyond purely descriptive analyses and establishing a robust, physically motivated picture of these active galactic nuclei.

Quasars as Cosmic Rulers: Reframing Our Understanding

Time Delay Cosmography represents a powerful technique for charting the expansion history of the universe by exploiting the unique phenomenon of gravitationally lensed quasars. When a quasar’s light is bent and amplified by the gravity of an intervening galaxy, multiple images of the quasar are created. Because light travels different paths, these images arrive at Earth at slightly different times – a ‘time delay’. Precisely measuring these delays, and combining this information with models of the lensing galaxy, allows cosmologists to determine distances to the quasar and, crucially, the Hubble Constant – a measure of the universe’s expansion rate. This method offers an independent way to calibrate the cosmic distance ladder, potentially resolving ongoing tensions between measurements derived from local and early-universe observations and providing a more accurate understanding of the fundamental parameters governing the cosmos.

The precision of cosmological measurements derived from time-delayed quasars hinges critically on the fidelity with which underlying stochastic processes are modeled. Subtle variations in these processes – those governing the fluctuations in quasar brightness – can introduce systematic errors that dwarf the statistical uncertainties. Consequently, researchers dedicate significant effort to developing flexible and robust modeling techniques, moving beyond simplistic assumptions about the quasar’s variability. These techniques often involve employing different kernel functions – mathematical descriptions of the correlation between brightness fluctuations at different times – and carefully assessing which best represents the observed data. Failure to accurately capture the true underlying behavior can lead to biased estimates of cosmological parameters, such as the Hubble constant and the density of dark energy, ultimately impacting the broader understanding of the universe’s expansion history and composition.

Recent investigations into gravitationally lensed quasars reveal that the brightness variations aren’t always consistent over time; specifically, analyses of three such quasars demonstrate that two – designated B 1608 + 656 and HE 0435 – 1223 – exhibit non-stationary behavior, meaning their average brightness changes over the observed period. This discovery underscores the limitations of traditional modeling techniques which assume a constant average brightness and highlights the necessity for employing more flexible mathematical functions, or ‘mean functions’, to accurately capture the observed variability. Without these adaptable models, subtle but significant errors can creep into cosmological measurements derived from time-delay cosmography, potentially impacting estimations of the universe’s expansion rate and other key parameters. The observed non-stationarity suggests that the underlying physical processes driving quasar brightness aren’t always static, demanding a more nuanced approach to data analysis.

The detailed analysis of gravitationally lensed quasars B 1608 + 656 and HE 0435 – 1223 indicates that the fluctuations in their brightness aren’t random, but rather governed by distinct stochastic processes. Researchers found that the variations in B 1608 + 656 are best described by an Exponential (E) kernel, suggesting a process where fluctuations tend to persist for a relatively short time. Conversely, HE 0435 – 1223’s brightness variations align more closely with a Matérn-32 kernel, indicating a smoother, more correlated process with longer-lasting fluctuations. This preference for different kernels isn’t merely a mathematical curiosity; it implies that the physical mechanisms driving the variability within these quasars – potentially related to accretion disk dynamics or turbulence – are demonstrably different, enriching the understanding of these cosmic beacons and refining cosmological measurements derived from their time delays.

Toward a More Complete Cosmic Picture

Nested sampling represents a sophisticated computational technique for determining the Bayesian evidence, a crucial quantity in model selection. This method efficiently explores the parameter space of a given model, even in high dimensions, by iteratively identifying and removing parameter combinations with low probability. Unlike traditional methods that may struggle with complex, multi-dimensional models, nested sampling intelligently focuses computational effort on the most promising regions, enabling a robust calculation of the Z-statistic. This allows researchers to directly compare the plausibility of different models – for instance, distinguishing between competing theories of quasar variability or cosmological parameters – by quantifying the ratio of their Bayesian evidences. The resulting evidence values provide a formal measure of how well each model explains the observed data, facilitating a more objective and statistically sound approach to scientific inquiry.

The determination of which theoretical models best explain observed phenomena relies heavily on Bayesian evidence calculation. This approach doesn’t merely assess if a model fits the data, but rather quantifies the relative plausibility of competing models given the evidence. In the context of quasar variability and cosmology, Bayesian analysis allows researchers to compare models describing the physical processes driving changes in quasar brightness, or different cosmological parameters influencing the universe’s expansion. By calculating the Bayesian evidence – essentially the probability of observing the data given a specific model – scientists can statistically determine which model is most likely to be correct, moving beyond simple goodness-of-fit measures and providing a robust framework for understanding the universe and the energetic objects within it. This process helps refine our understanding of dark energy, black hole physics, and the fundamental processes governing the cosmos.

Ongoing research endeavors are poised to significantly enhance current cosmological models by integrating increasingly sophisticated physical processes into analyses of quasar variability. This includes accounting for effects such as complex accretion disk dynamics, radiative transfer in extreme environments, and the influence of intervening absorbers along the line of sight. Crucially, these advancements will be coupled with the observation of a substantially larger cohort of quasars, leveraging next-generation telescopes and dedicated sky surveys. By expanding the statistical power of these studies, scientists aim to not only refine existing parameters that govern the universe’s expansion and composition, but also to potentially unveil previously unknown physical mechanisms driving quasar behavior and shaping the cosmos itself. This combined approach promises a more complete and nuanced understanding of the universe’s evolution and its fundamental properties.

The analysis of quasar light curves, as detailed in this work, reveals a humbling truth about modeling complex systems. Any attempt to fully capture the intrinsic variability of an accretion disc – a process inherently non-stationary – feels akin to chasing shadows. As Werner Heisenberg observed, “The more precisely the position is determined, the less precisely the momentum is known.” This echoes the challenge presented by time delay cosmography; increasing the precision of cosmological parameter estimation demands accounting for the subtle, evolving nature of quasar emissions. The Bayesian framework, while powerful, doesn’t erase the fundamental uncertainty-it merely provides a rigorous way to navigate it. Any hypothesis about singularities, or in this case, quasar behavior, is just an attempt to hold infinity on a sheet of paper.

Beyond the Horizon

The application of Gaussian Processes to quasar light curves, as detailed within, offers a refinement, not a resolution. It allows for a more nuanced accounting of non-stationarity-the frustrating reality that celestial objects rarely adhere to the simplifying assumptions of static models. Yet, increased flexibility in modeling merely highlights the limits of current understanding. The cosmos generously shows its secrets to those willing to accept that not everything is explainable. The accretion discs, the very engines powering these distant beacons, remain stubbornly complex, their intrinsic variability often mirroring-and perhaps exceeding-the precision of any observational technique.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on more sophisticated kernel methods, attempts to capture the full breadth of quasar behavior. However, the deeper challenge lies in distinguishing between genuine cosmological signals and the inherent ‘noise’ of the source itself. Time delay cosmography, while elegant in principle, is perpetually haunted by the possibility of mistaking an echo of the quasar’s own internal dynamics for a reflection of the universe’s expansion.

Black holes are nature’s commentary on human hubris. The pursuit of ever-finer measurements risks becoming an exercise in self-deception, a quest to impose order on a fundamentally chaotic system. Perhaps the most fruitful path lies not in eliminating uncertainty, but in embracing it, acknowledging that the universe is under no obligation to reveal its secrets-or to conform to expectations.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11264.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Samson: A Tyndalston Story Studio Wants Players to Learn Street Names, Manage Hour-to-Hour Pressure

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- “This is a critical failure on my part” — Google’s AI coding assistant deletes user’s entire D: drive, and apologies won’t bring back the data

2026-02-14 09:01