Author: Denis Avetisyan

Despite achieving high scores on standard tests, large language models can exhibit surprising inconsistencies, leading to unreliable scientific results.

Systematic disagreement among models and differing error profiles reveal a ‘benchmark illusion’ that threatens reproducibility in AI-assisted research.

Despite growing reliance on large language models (LLMs) for scientific tasks, apparent convergence on benchmark evaluations can mask substantial underlying disagreement. This is the central argument of ‘Benchmark Illusion: Disagreement among LLMs and Its Scientific Consequences’, which reveals that LLMs achieving comparable accuracy on reasoning benchmarks like MMLU-Pro and GPQA still exhibit significant discrepancies-up to 66%-in their responses. These hidden disagreements propagate into research outcomes, potentially altering estimated treatment effects in re-analyses of published studies by over 80%, and raising concerns about reproducibility in AI-assisted science. If benchmark performance obscures fundamental model divergence, how can we ensure reliable and consistent results when deploying LLMs for complex scientific inference?

The Illusion of Scientific Precision

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into scientific workflows is rapidly accelerating, offering potential advancements in areas like hypothesis generation and data analysis. However, this increasing reliance is tempered by legitimate concerns regarding their inherent reliability. While LLMs excel at identifying patterns and generating text that appears scientifically sound, they often lack true understanding of the underlying principles and can confidently produce inaccurate or misleading information. This stems from their training on vast datasets of text, where correlation is frequently mistaken for causation, and the models are optimized for fluency rather than factual correctness. Consequently, researchers are actively investigating methods to assess and mitigate the risks associated with deploying LLMs in critical scientific applications, focusing on techniques to verify outputs and ensure alignment with established scientific knowledge.

The perception that strong performance on established benchmark datasets guarantees reliable scientific inference is increasingly challenged by observed discrepancies in practical applications. While these datasets offer a standardized measure of ability, they often fail to capture the nuances and complexities inherent in real-world scientific problems. A model excelling at answering questions within a curated dataset may falter when confronted with novel data, ambiguous information, or the need for genuine causal reasoning. This divergence suggests that high scores can be misleading, creating a false sense of security regarding a model’s trustworthiness and potentially leading to inaccurate conclusions or flawed experimental designs. Consequently, evaluating scientific inference capabilities demands moving beyond simple benchmark assessments toward more robust and ecologically valid validation strategies.

Beyond Random Noise: Uncovering Systematic Errors

Large Language Models (LLMs), while susceptible to inaccuracies from random error, frequently exhibit systematic errors. These are not isolated incidents of incorrect output, but rather consistent biases demonstrably correlated with specific input conditions, model parameters, or inherent limitations in the training data. Unlike random error which averages out with sufficient data, systematic error introduces a predictable skew in the model’s responses, potentially leading to consistently inaccurate or unfair outcomes across defined subsets of inputs. This means that even with increased data volume, these biases will persist and may even be amplified if not identified and addressed, differentiating them from purely stochastic fluctuations in output.

The ‘Measurement Error Framework’ utilizes statistical techniques, including error covariance matrices and attenuation correction, to deconstruct observed variances in LLM outputs and isolate the contribution of systematic biases. This framework moves beyond treating inaccuracies as random noise by demonstrating that consistent deviations are attributable to flaws in the model’s training data, architecture, or inference process. Specifically, it allows researchers to quantify the magnitude of these biases and distinguish them from genuine signal, providing a means to estimate the true relationship between LLM outputs and ground truth, even when obscured by systematic error. Analysis using this framework has revealed that LLM biases are not uniformly distributed but often correlate with specific demographic groups or input characteristics, highlighting the structural nature of these errors.

Regression analysis offers a means to model systematic errors in Large Language Models (LLMs) by establishing a statistical relationship between observed outputs and underlying biases. However, the accuracy of these models is heavily contingent on the quality of the training data; biased datasets will inevitably lead to a skewed regression model, reinforcing and potentially amplifying existing systematic errors. Furthermore, the chosen model assumptions – such as linearity or specific functional forms – can introduce inaccuracies if they do not accurately reflect the true relationship between input features and the observed biases. Therefore, careful consideration of data provenance, thorough validation of model assumptions, and robust error analysis are essential to prevent regression analysis from generating misleading or inaccurate estimations of systematic errors in LLMs.

The Annotation Trap: Where Human Bias Creeps In

Annotation, critical for supervised and reinforcement learning paradigms used in Large Language Model (LLM) training, introduces systematic errors through multiple sources. Human annotators exhibit inherent biases, stemming from their individual backgrounds, interpretations of instructions, and subjective judgments. Inconsistencies arise both within a single annotator’s labeling – due to fatigue or evolving understanding – and between multiple annotators presented with the same data. These errors propagate directly into the training dataset, skewing the model’s learning process and ultimately impacting performance metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall. The severity of this impact is dependent on the task complexity, the clarity of annotation guidelines, and the quality control measures implemented during the labeling process.

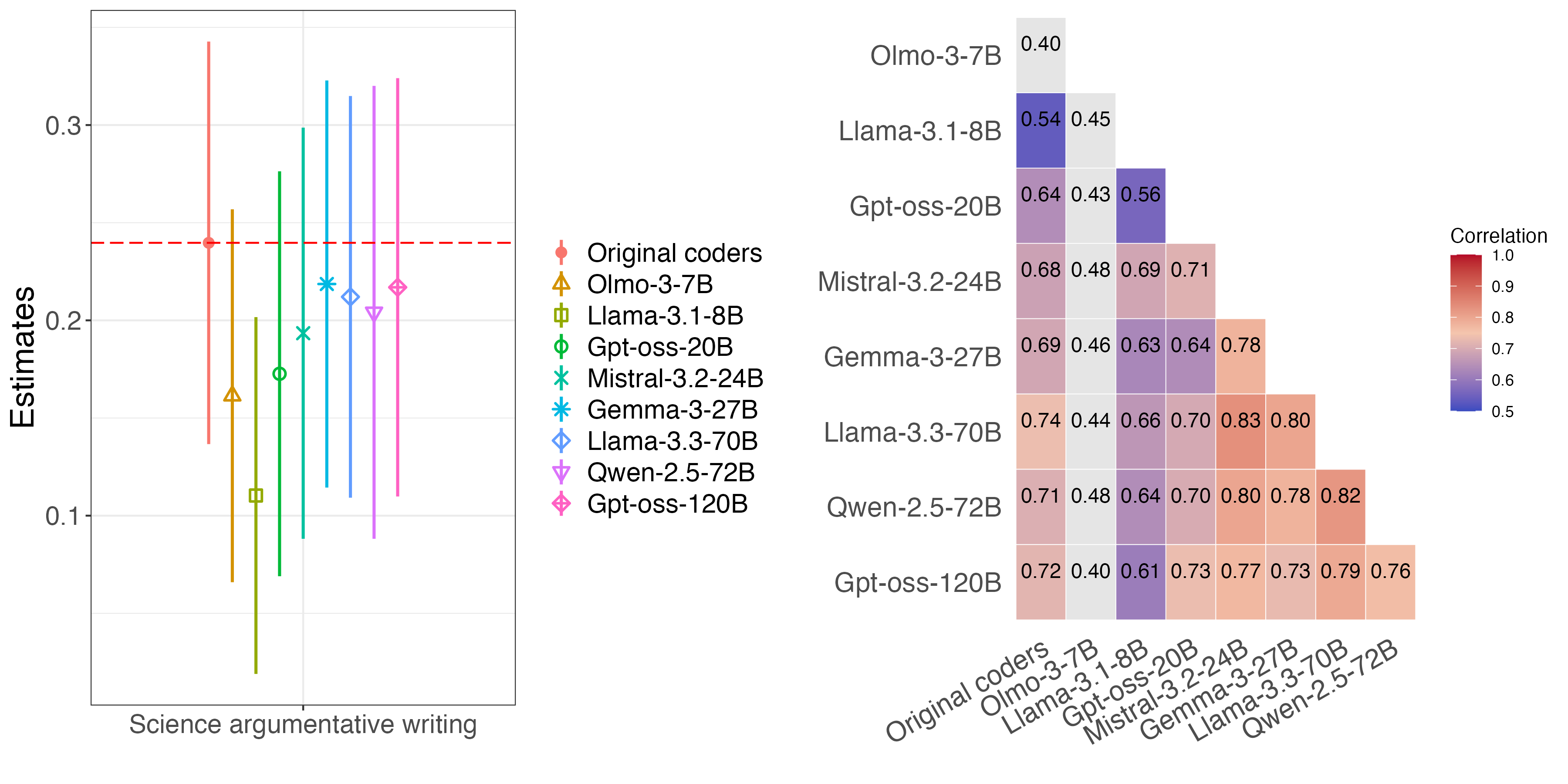

Research by Kim et al. (2021) and Rozenas and Stukal (2019) establishes a direct correlation between the quality of data annotation and the performance of language models. The Kim et al. study demonstrated that inconsistencies in human annotation directly translate to errors in model predictions, particularly in nuanced tasks requiring complex reasoning. Similarly, Rozenas and Stukal’s work highlighted that variations in annotator judgment – even among experts – significantly impact model training and evaluation, leading to potentially unreliable results if annotation quality is not rigorously controlled and consistently applied across datasets.

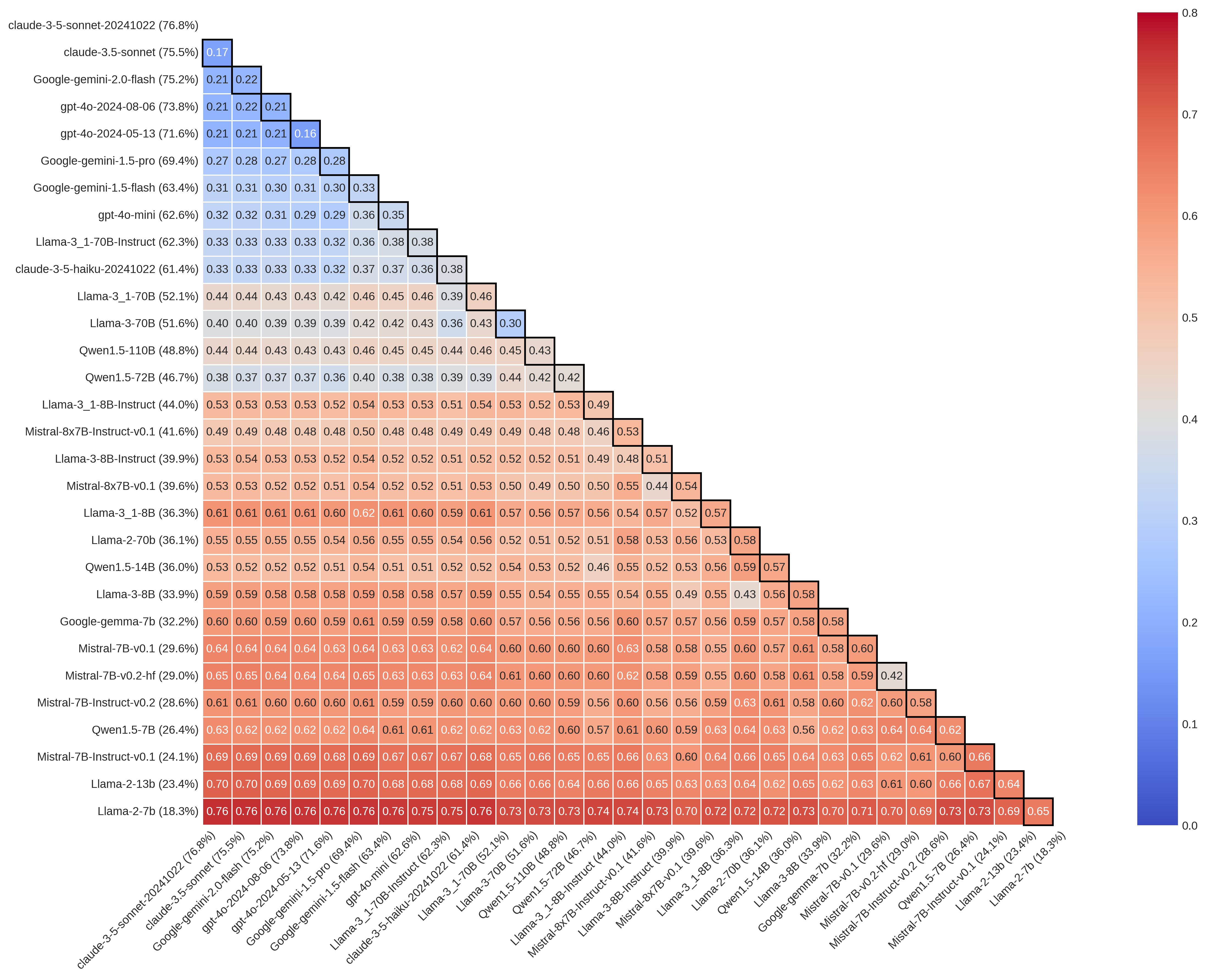

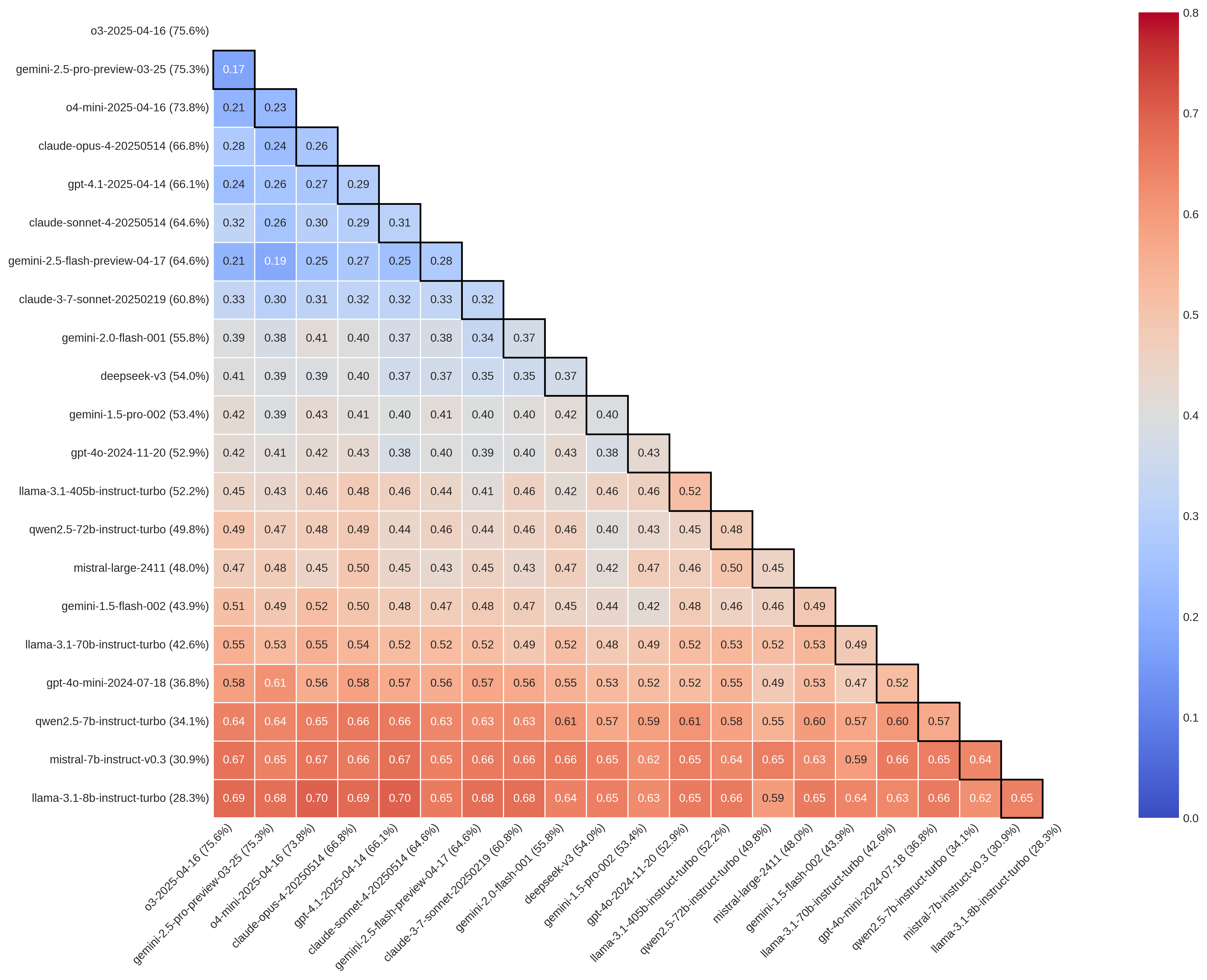

Reasoning benchmarks, such as MMLU-Pro and GPQA, are constructed using annotated datasets to evaluate large language model performance; however, this reliance introduces the potential for Benchmark Illusion. Observed pairwise disagreement rates within these datasets are substantial, ranging from 16-76% on MMLU-Pro and 17-70% on GPQA. These rates indicate significant inconsistency in the ‘ground truth’ annotations, meaning that even human annotators do not consistently agree on correct answers. Consequently, reported accuracy scores on these benchmarks may be artificially inflated, as models can achieve high scores by simply replicating the most common, but not necessarily correct, annotation.

Beyond the Score: What Consistent Performance Actually Means

Despite achieving seemingly high scores on standardized benchmarks, large language models (LLMs) frequently exhibit substantial disagreement when presented with the same scientific questions, a phenomenon known as high ‘pairwise disagreement’. This indicates that benchmark accuracy, while a useful metric, offers a limited view of an LLM’s true reliability. The models don’t simply arrive at different answers due to random chance; instead, consistent patterns of divergence suggest underlying inconsistencies in their reasoning processes. This lack of consistent performance raises significant concerns when applying LLMs to scientific inquiry, as a single benchmark score cannot guarantee replicable or trustworthy conclusions across different models, even when analyzing the same data or posing the same question.

While inherent stochasticity, or ‘random error’, inevitably introduces some variation in large language model outputs, it is the presence of ‘systematic error’ that truly drives divergent conclusions. These systematic biases, stemming from differing training data, model architectures, or inherent limitations in understanding, cause models to consistently lean towards particular interpretations, even when presented with identical inputs. This isn’t merely noise; it represents a fundamental skew in processing that amplifies discrepancies and leads to substantial disagreements – potentially reversing conclusions or generating dramatically different estimates of effect sizes, as demonstrated in recent studies quantifying up to an 84% variance in treatment effect estimations across various LLMs. Consequently, the reliability of LLM-derived insights hinges not solely on minimizing random fluctuations, but on identifying and mitigating these underlying, systematic distortions.

Variations in large language model (LLM) responses aren’t merely nuances in phrasing; they directly impact the conclusions drawn from scientific data. Recent research demonstrates a substantial divergence in estimated treatment effects when analyzed by different LLMs – one study revealed discrepancies as high as 84%. This inconsistency isn’t limited to quantitative differences; instances have been documented where LLMs arrive at opposing conclusions relative to the original research findings, effectively reversing interpretations of the same data. Such variability underscores the critical need for caution when employing LLMs for scientific synthesis, as the perceived reliability of results is demonstrably affected by the specific model utilized and highlights the potential for misinterpreting evidence-based research.

The Pursuit of Robustness: Beyond Faster Inference

The practical deployment of large language models (LLMs) relies heavily on efficient inference engines like VLLM, designed to maximize throughput and minimize latency. However, despite substantial advancements in infrastructure and optimization techniques, LLMs continue to exhibit systematic errors – predictable, recurring failures that aren’t simply random noise. These aren’t issues of speed, but of reliability; even with swift processing, models can consistently generate factually incorrect, biased, or nonsensical outputs under specific conditions. This persistence of systematic errors highlights a critical gap between optimized performance metrics and genuine robustness, suggesting that simply running models faster doesn’t resolve fundamental limitations in their reasoning or knowledge representation. Further investigation is therefore needed to pinpoint the origins of these errors and develop strategies for consistent, trustworthy LLM performance.

The method by which a large language model generates text – its decoding strategy – significantly influences the consistency of its responses. While approaches like ‘Greedy Decoding’ prioritize selecting the most probable token at each step for speed and simplicity, this can lead to predictable, and sometimes repetitive, outputs. Other strategies, such as beam search or sampling methods, introduce more randomness to explore a wider range of possibilities, potentially yielding more diverse and nuanced responses, but also increasing the risk of inconsistencies. Consequently, careful consideration and evaluation of different decoding strategies are crucial for applications where reliability and predictable behavior are paramount, demanding a trade-off between response quality, diversity, and consistency.

Continued advancement in large language model (LLM) evaluation necessitates a shift beyond conventional benchmark scores, which often provide a limited and potentially misleading view of true reliability. Future research must prioritize the development of methodologies capable of pinpointing systematic errors – predictable, recurring failures in LLM responses – and devising strategies to mitigate them. This involves not only improving error detection, but also understanding the underlying causes of these failures, potentially linked to biases in training data or limitations in model architecture. A robust assessment framework will require probing LLMs with carefully constructed adversarial examples and analyzing responses for nuanced patterns of incorrect reasoning, ensuring that performance claims are substantiated by evidence of genuine understanding and consistent, trustworthy behavior, rather than simply reflecting memorization or superficial pattern matching.

The pursuit of ever-more-complex models consistently forgets a fundamental truth: disagreement isn’t bugs, it’s features – and features quickly become liabilities. This paper meticulously details how Large Language Models, despite achieving similar benchmark scores, arrive at wildly different conclusions, creating what they call a ‘benchmark illusion’. It’s a fancy term for what happens when you build a house of cards on shifting sand. Linus Torvalds famously said, “Most programmers think that if their code works, they’re clever. But it’s not about being clever; it’s about getting things done.” These models ‘get things done’ by confidently presenting conflicting data, and someone, inevitably, will treat it as gospel. The error profiles, differing as they are, will be smoothed over with statistics, and the documentation will, predictably, lie again. It’s not a failure of AI; it’s a reminder that complex systems inevitably accrue tech debt – emotional debt with commits, if you will.

The Mirage of Progress

The observation of systematic disagreement among ostensibly high-performing Large Language Models isn’t a surprising revelation, merely a formalization of a long-held suspicion. Any metric claiming to capture ‘understanding’ should be treated as a temporary convenience. The paper correctly identifies the ‘benchmark illusion’ – the belief that a single, high score translates to reliable scientific inference. The problem isn’t that these models fail benchmarks, but that consistent success merely indicates a shared set of biases, not truth-seeking. Documentation of these biases, naturally, will prove to be a collective self-delusion.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on quantifying these disagreement profiles, attempting to build ‘ensembles’ to mitigate model variance. This is, predictably, treating a symptom, not the disease. A truly stable system, one worthy of trust, isn’t achieved through aggregation, but through demonstrable, reproducible errors. If a bug is reproducible, it is a feature. The real challenge lies not in making models more accurate, but in developing rigorous methods for identifying where they consistently fail – and accepting those failures as fundamental limitations.

The pursuit of ever-larger models, trained on ever-larger datasets, feels increasingly like an attempt to outrun the inevitable. Anything self-healing just hasn’t broken yet. Perhaps the most productive line of inquiry will involve a deliberate embrace of ‘low-resource’ models, systems simple enough to be fully understood, and whose limitations are readily apparent. The illusion of intelligence is cheap; genuine understanding requires honest accounting.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11898.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Sunday Rose Kidman Urban Describes Mom Nicole Kidman In Rare Interview

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- 32 Kids Movies From The ’90s I Still Like Despite Being Kind Of Terrible

2026-02-15 23:46