Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that standard machine learning techniques can inadvertently corrupt a model’s underlying understanding of physical principles, impacting its ability to accurately simulate the world.

A non-invasive probing framework demonstrates that adaptive training can lead to representational collapse in learned world models, necessitating methods to preserve the integrity of latent physical representations.

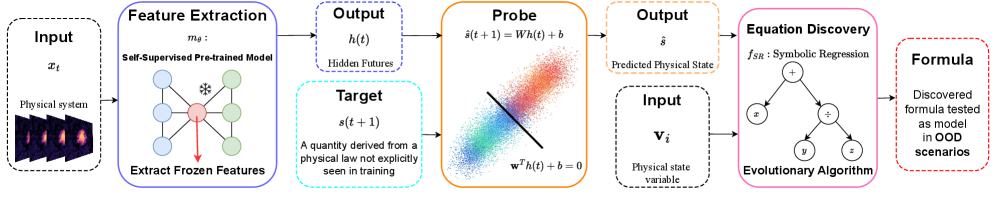

Determining whether neural networks truly learn underlying physical laws, or merely exploit statistical correlations, remains a central challenge in scientific machine learning. In the work ‘The Observer Effect in World Models: Invasive Adaptation Corrupts Latent Physics’, we demonstrate that standard evaluation techniques-specifically, adaptation-based methods like fine-tuning-can actively corrupt the learned representations they seek to measure. Our non-invasive probing framework, PhyIP, reveals linearly decodable physical quantities from frozen representations, recovering internal energy and Newtonian scaling even under out-of-distribution shifts. This finding suggests that the act of observing-through adaptation-can fundamentally alter the system being observed, and raises the question of how to accurately assess genuine physical understanding in neural world models.

The Illusion of Understanding: Why We Chase Shadows in Neural Networks

Recent advances in self-supervised learning (SSL) have yielded models capable of surprisingly accurate predictions regarding the evolution of physical systems, ranging from fluid dynamics to the behavior of soft materials. However, the mechanisms driving this predictive power remain largely unknown; these models function as ‘black boxes’, where the internal representations learned from unlabeled data are difficult to interpret. While a model may accurately forecast a system’s trajectory, discerning whether it has genuinely captured underlying physical principles – such as conservation laws or symmetries – versus simply memorizing patterns within the training data is a significant challenge. This opacity hinders trust in the models’ predictions, especially when extrapolating beyond the training data or applying them to novel scenarios, and limits the potential for these systems to contribute to new scientific discovery.

Determining whether neural networks genuinely grasp underlying physical principles, as opposed to merely memorizing training data, is paramount for deploying these models in real-world scientific applications. A system that relies on pattern recognition alone may falter when confronted with scenarios outside its training distribution – a critical limitation in fields like climate modeling or materials discovery where predictive accuracy in novel conditions is essential. Establishing true physical understanding would imply the model can generalize to unseen situations, reason about physical constraints, and even suggest new hypotheses – capabilities far beyond simple memorization. Consequently, rigorous evaluation methods are needed to differentiate between superficial pattern matching and a deeper, more robust comprehension of the physical world, ensuring reliable and trustworthy predictions.

Current techniques for probing the learned representations within neural networks often necessitate alterations to the model itself, a practice that introduces a critical methodological challenge. Intervening in a network’s structure – be it through weight pruning, node activation analysis, or adding perturbative inputs – risks fundamentally changing the system being examined. This intervention can inadvertently destroy the very physical understanding the researchers are attempting to measure, creating a distorted picture of the model’s true capabilities. The act of looking, in essence, changes what is being looked at, raising questions about whether observed behaviors reflect inherent knowledge or simply the response to an artificial disturbance. Consequently, developing non-invasive methods for evaluating these representations is paramount to accurately gauging a model’s grasp of underlying physical principles and ensuring the reliability of its predictions.

Non-Invasive Physical Probing: A Method for Cutting Through the Noise

Non-Invasive Physical Probe (PhyIP) is a methodology for evaluating a model’s understanding of physical principles without altering the model itself. This is achieved by extracting the activations – the output values – from a specific layer within the neural network and fixing, or ‘freezing’, these values. These frozen activations then serve as input features for a separate linear regression model. By training this regression model to predict known physical quantities, PhyIP establishes a direct, quantifiable relationship between the model’s internal representations – as captured by the frozen activations – and its ability to reason about the physical world. The technique focuses on analyzing existing model behavior rather than requiring any changes to the model’s architecture or training process.

Non-Invasive Physical Probing (PhyIP) establishes a quantifiable link between a model’s internal state and physical properties through linear regression. Specifically, frozen activations – the fixed output values of a neural network layer – are used as input features to a linear regression model. The target variable for this regression is a measurable physical quantity, such as total internal energy. The resulting regression coefficients and R-squared value provide a numerical assessment of how well the model’s learned representations correlate with, and therefore reflect understanding of, the physical property in question. This allows for a direct, data-driven measure of the model’s ‘understanding’ without requiring explicit interpretation of the activations themselves.

The Non-Invasive Physical Probe (PhyIP) methodology is designed to mitigate the ‘observer effect’ – alterations to a system caused by the measurement process itself – by exclusively utilizing frozen activations as proxies for physical quantities. Traditional model assessment techniques often require modification of the neural network’s architecture or the introduction of additional training procedures, which can inadvertently influence the model’s behavior and obscure its pre-existing knowledge. PhyIP, however, operates without altering the model, ensuring that the assessment reflects the model’s inherent understanding of the physical phenomena without introducing artifacts caused by the probing process. This approach yields a more accurate and reliable evaluation of the model’s capabilities, as it directly assesses the relationship between internal representations and physical quantities in a non-interfering manner.

Testing the Limits: PhyIP Across Complex Astrophysical Systems

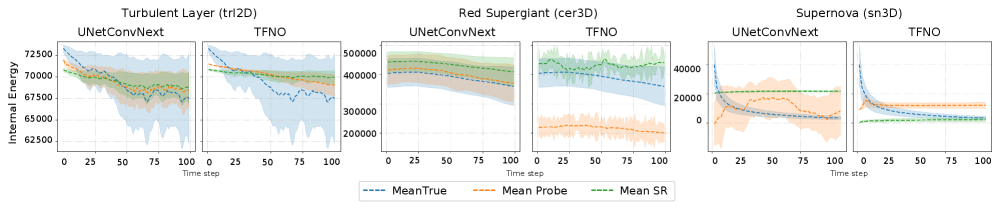

PhyIP was evaluated using simulation-based learning (SSL) models trained on data generated from three distinct astrophysical simulations: turbulent radiative layers (TRL-2D), red supergiant (RSG-3D) envelopes, and supernova explosions. These simulations represent a range of physical phenomena and dimensionality, allowing for assessment of PhyIP’s generalizability across complex physical systems. The TRL-2D simulation models convection in stellar atmospheres, RSG-3D simulates the outer layers of evolved stars, and the supernova explosion models represent the final stages of massive star evolution. Utilizing these diverse datasets enabled a comprehensive validation of PhyIP’s capacity to analyze models operating on varying physical principles and scales.

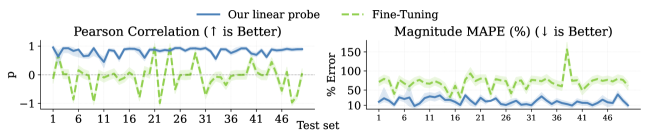

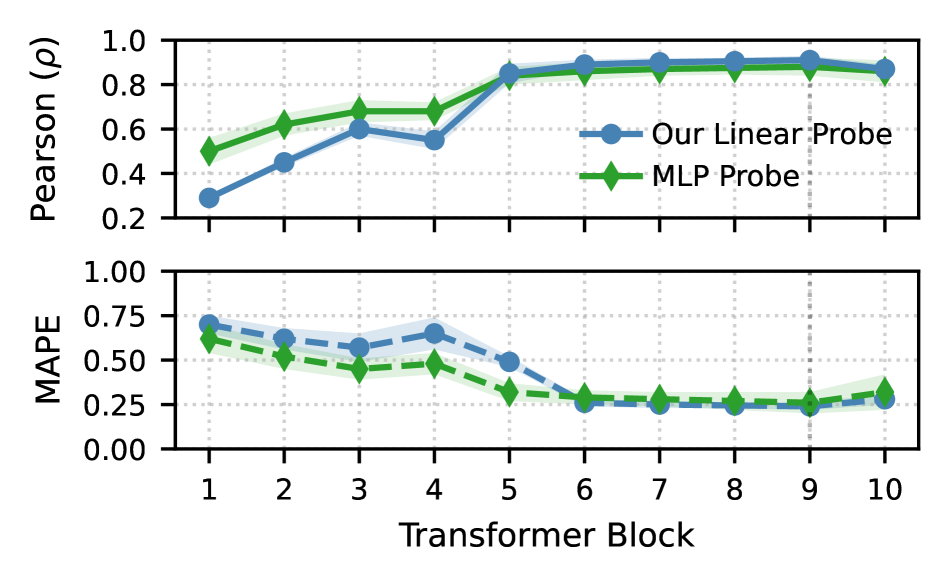

PhyIP effectively quantifies the predictive power of simulation models by demonstrating a strong correlation with performance on downstream tasks. Quantitative analysis across turbulent radiative layer (TRL-2D) and red supergiant (RSG-3D) models yielded a Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ) exceeding 0.90. This high correlation indicates that PhyIP accurately captures the model’s ability to predict physical quantities relevant to its intended application, providing a robust metric for evaluating and comparing different simulation models based on their predictive capabilities.

Analysis using PhyIP confirms the validity of the linear representation hypothesis within the tested simulation models. Specifically, in the TRL-2D simulation, PhyIP successfully recovered internal energy, demonstrating a ratio of E \approx 1.5PE, where E represents internal energy and PE represents potential energy. This recovery of a physically meaningful quantity supports the feasibility of PhyIP as a non-invasive method for analyzing and interpreting the internal representations learned by these complex physical models without requiring access to internal gradients or model parameters.

The Illusion of Insight: Why Non-Invasive Probing Matters

Traditional methods of assessing a model’s internal reasoning, like fine-tuning or adding trainable probing layers, often inadvertently reshape the very representations they aim to analyze. This phenomenon, termed ‘representational collapse’, occurs as the adaptation process prioritizes performance on the probing task over preserving the original, pre-trained knowledge embedded within the network. Consequently, observed behaviors during probing may reflect the learned biases of the adaptation process itself, rather than an accurate depiction of the model’s inherent understanding. This creates a critical challenge in interpreting probe results, as it becomes difficult to discern whether a model successfully applied existing knowledge or simply learned a new association to solve the probing task, undermining the validity of the assessment.

PhyIP distinguishes itself through a non-invasive approach to probing neural networks, a methodology crucial for accurately gauging a model’s underlying physical intuition. Unlike techniques such as fine-tuning or incorporating trainable layers – which can fundamentally alter the learned representations within the network – PhyIP leaves the original model untouched. This preservation of the initial state is paramount, as invasive adaptations risk inducing ‘representational collapse’, where the probe’s training inadvertently overwrites the very knowledge it aims to assess. Consequently, PhyIP provides a more faithful and reliable measurement of the model’s pre-existing physical understanding, offering insights into its inherent capabilities without the confounding influence of adaptation-induced distortions. This allows for a clearer determination of what the model already knows, rather than what it has been trained to report during the probing process.

Investigations utilizing PhyIP successfully demonstrated the recovery of the inverse-square law – a fundamental principle stating force is proportional to one over the distance squared F∝1/r² – a feat that proved elusive with traditional, invasive probing methods. This outcome highlights PhyIP’s capacity for non-destructive analysis, allowing for a more accurate extraction of inherent physical understanding within the model. Furthermore, rigorous error analysis establishes a quantifiable bound on the linear probe’s accuracy: ≤C₁⋅ϵ+C₂[KΦ²⋅Var(x)] + 𝒪(Δt⁴), where C₁ and C₂ represent constants, ϵ accounts for noise, KΦ² relates to the probe’s sensitivity, Var(x) represents the variance of the input data, and Δt⁴ indicates the contribution of higher-order temporal effects, ultimately providing a precise understanding of the probe’s limitations and reliability.

The pursuit of increasingly complex world models inevitably leads to representational collapse, a phenomenon this paper carefully dissects. It’s a familiar story; researchers chase adaptation, seeking improved performance on downstream tasks, only to inadvertently corrupt the very physical understanding they aimed to capture. As Linus Torvalds observed, “Most good programmers do programming as an exercise in avoiding work.” This neatly encapsulates the core issue – the drive for immediate gains often overshadows the need to preserve a robust, interpretable foundation. The elegance of a theoretical framework quickly gives way to pragmatic hacks when faced with the realities of production data, much like a carefully crafted system inevitably accruing technical debt. This study underscores that truly understanding a model requires non-invasive probing-a careful examination of what’s already there, rather than relentless modification.

What’s Next?

The insistence on ‘world models’ as some kind of general intelligence shortcut feels… optimistic. This work, demonstrating how readily these learned representations succumb to even standard adaptation, suggests a fundamental problem: anything called ‘scalable’ simply hasn’t been tested properly. The notion that a network can simultaneously learn a robust, generalizable physics and perform downstream tasks without some form of representational collapse appears, at best, naive. One suspects the logs will eventually confirm this.

Future work will likely focus on increasingly elaborate ‘non-invasive’ techniques, attempting to peek inside the black box without disturbing the delicate house of cards within. A more fruitful, if less glamorous, direction might involve accepting that some degree of corruption is inevitable, and building systems resilient enough to tolerate it. Better one robust, slightly inaccurate monolith than a hundred lying microservices, each claiming perfect physical understanding.

Ultimately, the field chases a phantom: a perfectly disentangled representation of reality. Perhaps the real lesson here is that ‘understanding’ is not a static entity to be captured and stored, but a continuous process of interaction and refinement. The network, like any system, will adapt. The question isn’t whether it will forget the physics, but whether the forgetting is useful.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12218.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- Monster Hunter Stories 3’s character creator is officially revealed — and it features a cosmetic that’s normally paywalled in the mainline games

2026-02-15 03:35