Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research suggests that the subtle shifts in gravitational waves emitted by objects spiraling into rotating black holes could offer a unique window into the elusive realm of quantum gravity.

Analysis of Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals around Hayward black holes using space-based observatories demonstrates the potential for detecting quantum gravity effects through precise waveform measurements.

Despite the successes of general relativity, a complete theory unifying gravity with quantum mechanics remains elusive. This motivates the study, ‘Probing Quantum Gravity effects with Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals around Rotating Hayward Black Holes’, which investigates the potential to detect signatures of quantum gravity through observations of extreme mass-ratio inspirals orbiting a rotating Hayward black hole. The authors demonstrate that subtle dephasing in the emitted gravitational waveforms, induced by quantum corrections, may be detectable by the future LISA space-based observatory. Could high-precision gravitational wave astronomy therefore provide a pathway to probing the fundamental nature of spacetime at the Planck scale?

The Inevitable Failure of Classical Spacetime

Classical General Relativity, while remarkably successful in describing gravity, predicts the formation of spacetime singularities deep within black holes. These aren’t simply regions of intense gravity; they represent a fundamental breakdown in the known laws of physics. As matter collapses under gravity’s pull, General Relativity suggests it crushes to an infinitely dense point, a singularity where quantities like density, curvature of spacetime, and tidal forces become infinite. This poses a significant problem for physicists, as any physical theory is expected to remain well-behaved-finite and predictable-even under extreme conditions. The existence of singularities implies that General Relativity is incomplete and breaks down at these points, necessitating a more comprehensive theory of gravity that can accurately describe what happens at the very heart of a black hole – a challenge that motivates much of contemporary research in gravitational physics and quantum gravity.

The prediction of spacetime singularities within black holes represents a profound crisis for modern physics, challenging the very foundations of gravitational theory and cosmology. These points of infinite density and curvature, where the laws of physics as currently understood break down, indicate a fundamental incompleteness in General\, Relativity. A singularity isn’t merely a bizarre astronomical object; it signifies a limit to predictability, preventing the determination of what occurs within a black hole and potentially impacting the evolution of the universe itself. If singularities are physically real, they necessitate a revision of established physical principles, potentially demanding a quantum theory of gravity to accurately describe extreme gravitational conditions. The existence of singularities also raises questions about information loss, causality, and the initial conditions of the universe, issues that continue to drive theoretical research and motivate the search for alternative black hole models.

The Hayward black hole presents a fascinating resolution to the problematic singularities predicted by classical General Relativity. Instead of a crushing point of infinite density at the black hole’s center, this model proposes a fundamentally different internal structure – a non-singular core. This core, governed by a modified theory of gravity, avoids the breakdown of physical laws that plagues the standard black hole description. Critically, the Hayward metric allows for spacetime to remain finite and well-behaved even at the black hole’s center, offering a potential pathway to understanding what truly lies within these enigmatic objects. Furthermore, this alternative possesses an event horizon similar to the Schwarzschild black hole, meaning it still functions as a one-way surface from which nothing can escape, but with the crucial difference of a stable, non-singular interior that may offer insights into the fate of information falling into a black hole and potentially resolving the information paradox.

Constructing a Mathematically Sound Black Hole

The spinning Hayward black hole represents an extension of the original, spherically symmetric Hayward solution by incorporating rotational effects, modeled using the Kerr metric. This is achieved through the introduction of an angular momentum parameter, a, which defines the black hole’s spin. Unlike the Schwarzschild or Kerr solutions which contain singularities at the event horizon, the Hayward metric maintains a de Sitter-like core, preventing singularity formation. The inclusion of rotation is essential for astrophysical realism, as the vast majority of black holes observed are expected to be spinning. The spin parameter influences the ergosphere, the region surrounding the black hole where spacetime is dragged along with the rotation, and modifies the event horizon’s shape from spherical to oblate. Furthermore, the spinning Hayward solution allows for investigation of frame-dragging effects and their impact on accretion disk dynamics and energy extraction processes, making it a valuable tool for modeling more accurate representations of astrophysical black holes.

Quantum gravity corrections become significant at the Planck scale, approximately 10^{-{35}} meters, where gravitational effects are expected to be dominated by quantum phenomena. Classical general relativity breaks down at this scale, necessitating a framework incorporating quantum mechanics. These corrections manifest as modifications to the spacetime geometry, particularly near the singularity at the black hole’s core. Specifically, they introduce a minimum length scale, effectively resolving the singularity and preventing infinite densities.

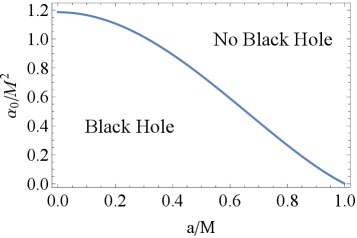

The dimensionless parameter α_0 serves as a quantitative measure of the magnitude of quantum gravity corrections within the Hayward black hole metric. By varying α_0, researchers can systematically investigate the influence of these corrections on the black hole’s event horizon, singularity structure, and overall spacetime geometry. A value of α_0 = 0 recovers the Schwarzschild solution, while non-zero values introduce deviations reflecting quantum effects; larger values of α_0 correspond to stronger quantum corrections and a potentially altered black hole interior. This parameterization allows for a controlled study of how quantum gravity might resolve the classical singularity problem and modify black hole thermodynamics.

Extracting Testable Predictions from Extreme Orbits

Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) consist of a compact object – typically a stellar-mass black hole, neutron star, or white dwarf – spiraling into a supermassive black hole (SMBH) with masses ranging from 10^5 to 10^7 solar masses. This substantial mass disparity allows for a large number of orbits prior to merger, resulting in gravitational waves that trace the spacetime geometry very close to the SMBH event horizon. Consequently, EMRIs provide a unique opportunity to test general relativity in the strong-field regime, probing deviations from the Kerr metric and potentially revealing information about the SMBH’s spin and the existence of additional parameters beyond those predicted by standard general relativity. The LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) observatory, due to its low-frequency sensitivity and space-based operation, is particularly well-suited to detect the gravitational waves emitted by these inspiral events.

The AAK (Analytic Accurate Kinematic) waveform model generates gravitational waveforms for Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) through a multi-stage analytic process. It begins with a post-Newtonian expansion to model the inspiral phase, providing accurate results when the small mass object is far from the massive black hole. As the objects approach merger, the model incorporates adiabatic approximations to track the slow change in orbital parameters, enabling efficient computation of the waveform’s frequency and phase evolution. This approach avoids computationally expensive numerical relativity simulations while maintaining sufficient accuracy for data analysis and parameter estimation in gravitational wave observatories like LISA; the model calculates the waveform’s amplitude and phase using \Psi_4 which describes the quadrupolar gravitational wave emission.

Software packages such as FastEMRIWaveforms are critical for generating the complex waveforms required to model Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs). These packages utilize pre-computed tables and efficient algorithms to rapidly produce waveform data across a wide range of binary parameters, significantly reducing the computational cost associated with gravitational wave data analysis. This accelerated waveform generation directly enables and speeds up parameter estimation studies, allowing researchers to more efficiently constrain the properties of EMRI sources and test predictions of general relativity with data from observatories like LISA. The speedup is achieved through techniques like interpolation and caching of computationally expensive calculations, making large-scale Bayesian inference feasible.

The Search for Quantum Gravity: A Precision Measurement

The universe’s most extreme gravitational environments, such as those surrounding merging black holes and neutron stars, provide an unprecedented opportunity to probe the elusive realm where quantum mechanics and gravity intersect. Current theoretical frameworks, like General Relativity, offer remarkably accurate descriptions of gravity, but break down under such intense conditions, hinting at the need for a more complete theory – quantum gravity. Gravitational wave detectors, capable of sensing ripples in spacetime, act as unique messengers from these strong-field regimes. By meticulously analyzing the characteristics of these waves – their amplitude, frequency, and particularly subtle phase shifts – scientists hope to detect deviations from the predictions of General Relativity. These deviations, potentially manifested as Δα₀ parameters in waveform models, could provide the first experimental evidence of quantum gravity effects, offering insights into the fundamental nature of spacetime itself and resolving long-standing conflicts between these two pillars of modern physics.

The Fisher Information Matrix serves as a cornerstone in the effort to discern subtle deviations from Einstein’s General Relativity, particularly those predicted by theories of quantum gravity. This mathematical tool allows researchers to quantify the precision with which parameters describing a physical system – in this case, potential quantum corrections to gravity – can be estimated from observational data. By calculating the curvature of the likelihood function, the Matrix effectively establishes a lower bound on the variance of any parameter estimate; a larger Fisher Information value indicates a greater sensitivity to that parameter and, therefore, a higher probability of detecting even minute quantum effects. In the context of gravitational wave astronomy, where signals are often buried in noise, the Fisher Information Matrix enables scientists to assess the detectability of these quantum corrections before extensive data analysis, optimizing observational strategies and informing the design of future detectors capable of probing the very fabric of spacetime at an unprecedented level of precision.

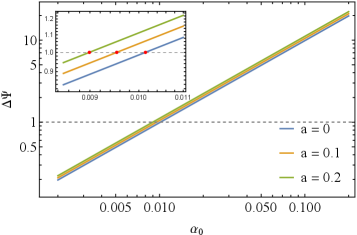

Extreme-mass-ratio inspirals (EMRIs) present a compelling opportunity to rigorously test the predictions of General Relativity, and recent research indicates these systems could potentially detect deviations with unprecedented precision. Through detailed analysis, scientists estimate that EMRIs may be able to measure a key parameter, α₀, with an error of just Δα₀ = 3.07 x 10⁻⁴. This level of accuracy represents a significant leap forward in the search for quantum gravity effects, as even minute discrepancies from General Relativity could signal the influence of quantum phenomena on spacetime. The potential to constrain, or even observe, these effects through gravitational wave astronomy opens a new frontier in fundamental physics, promising insights into the very fabric of reality at its most extreme scales.

A rigorous statistical analysis, employing the Fisher Information Matrix, reveals the potential precision with which deviations from classical gravity can be measured through gravitational wave observations. Specifically, simulations involving Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) and a signal-to-noise ratio of 150 indicate an achievable uncertainty of Δα₀ = 3.07 \times 10^{-4} in determining the parameter α₀, which represents a key quantum correction to the gravitational waveform. This level of precision suggests that future gravitational wave detectors, such as the Einstein Telescope or Cosmic Explorer, may be capable of not only detecting, but also accurately characterizing, subtle quantum gravity effects embedded within the signals emitted by these extreme astrophysical events, offering a direct pathway to testing the fundamental nature of spacetime.

The subtle fingerprints of quantum gravity may manifest not as dramatic bursts of energy, but as delicate alterations to the phase of gravitational waves. These waves, ripples in spacetime itself, are predicted by Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, but quantum gravity proposes minute deviations from this classical description. Researchers find that these quantum effects introduce a slight “dephasing” – a shifting of the wave’s crests and troughs – within the gravitational waveform. Detecting this dephasing requires extraordinarily precise measurements, as the shifts are incredibly small, but the potential reward is immense: direct evidence that gravity, at its most fundamental level, is governed by the principles of quantum mechanics. This dephasing, though subtle, offers a promising avenue for probing the elusive realm where gravity and quantum physics converge, potentially unlocking a deeper understanding of the universe’s most fundamental forces.

A Multi-Messenger Approach to Unveiling the Cosmos

Future gravitational wave astronomy hinges on the development of space-based observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), Taiji, and Tianqin. These ambitious projects are uniquely positioned to detect gravitational waves at significantly lower frequencies than ground-based detectors like LIGO and Virgo. This capability opens a new window onto the universe, allowing scientists to observe phenomena inaccessible from Earth. Specifically, these missions target the faint ripples generated by Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) – the mergers of stellar-mass black holes with supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. The detection of EMRIs will not only confirm predictions of general relativity in the strong-field regime but also provide unprecedented insights into the growth and evolution of supermassive black holes, and potentially reveal deviations from Einstein’s theory that could hint at the nature of quantum gravity.

Space-based gravitational wave detectors, unlike their ground-based counterparts, face unique challenges from noise sources like solar wind and instrumental jitter. To mitigate these disturbances, a technique called Time-Delay Interferometry (TDI) is essential. TDI doesn’t attempt to eliminate the noise, but rather to cleverly exploit its commonality across multiple spacecraft. By precisely measuring the time delay between signals received at different points in space – forming virtual interferometers – the common noise can be cancelled out through differential measurements. This relies on maintaining incredibly accurate timing and precise knowledge of the spacecraft’s relative positions. Different TDI configurations, such as first-, second-, and third-generation schemes, offer varying levels of noise suppression and sensitivity to different gravitational wave frequencies. Effectively, TDI transforms the limitations of a noisy space environment into an opportunity to isolate the subtle ripples in spacetime predicted by Einstein’s theory.

The convergence of data from diverse gravitational wave observatories – ground-based facilities like LIGO and Virgo, and future space-based missions such as LISA – promises a dramatic leap in sensitivity and the potential to probe the most elusive aspects of the universe. This multi-observatory approach isn’t simply about confirming detections; it’s about unlocking a more complete picture of gravitational wave sources and, crucially, providing a unique window into quantum gravity. By combining signals detected across different frequency bands and leveraging the distinct noise profiles of each instrument, scientists can effectively filter out interference and enhance the detection of weak signals. This improved sensitivity is predicted to reveal subtle deviations from general relativity, potentially providing the first empirical evidence of quantum gravity – a long-sought theory that reconciles Einstein’s gravity with the principles of quantum mechanics. Specifically, the ability to precisely measure the polarization and timing of gravitational waves, when combined across multiple detectors, could reveal the granular structure of spacetime itself, hinting at the fundamental quantum nature of gravity at the Planck scale.

The investigation into Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) reveals a commitment to rigorous mathematical frameworks for understanding the universe. The article meticulously details how subtle waveform dephasing, detectable through advanced time-delay interferometry, offers a pathway to probe the elusive realm of quantum gravity. This echoes Mary Wollstonecraft’s assertion: “The mind should be strengthened by truth, and not weakened by delusion.” Just as Wollstonecraft championed clarity of thought, the research prioritizes precise, mathematically sound methods to discern genuine quantum effects from noise, ultimately seeking a truthful representation of gravitational phenomena surrounding Hayward black holes. The pursuit isn’t merely about observing; it’s about establishing a provable understanding of the cosmos.

Future Directions

The assertion that Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) may serve as probes of quantum gravity, while conceptually appealing, rests upon the precise characterization of waveform dephasing. Current models of Hayward black holes, and indeed any attempt to model quantum gravity effects near a black hole horizon, are necessarily approximations. The true metric, if it exists as a well-defined object, remains elusive. Further work must focus not simply on fitting parameters, but on rigorously defining the limits of these approximations – specifically, establishing a mathematically sound basis for their validity, or conversely, identifying the precise conditions under which they demonstrably fail.

The reliance on time-delay interferometry, and the Fisher Information Matrix as a metric for parameter estimation, introduces further layers of complexity. The practical limitations of space-based observatories-noise sources, detector sensitivity, and the sheer computational cost of waveform analysis-cannot be dismissed as mere engineering challenges. These are fundamental constraints that dictate the achievable precision, and therefore, the theoretical reach of any proposed quantum gravity test. A more complete treatment must integrate these observational realities into the theoretical framework, rather than treating them as afterthoughts.

Ultimately, the question is not merely whether EMRIs can detect quantum gravity, but whether they offer a uniquely provable pathway to doing so. Without a clear, mathematically defined signal-a deviation from General Relativity that is demonstrably attributable to quantum effects and distinguishable from other sources of uncertainty-the pursuit remains a beautiful, but potentially sterile, exercise in theoretical speculation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.07436.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Survivor’s Colby Donaldson Admits He Almost Backed Out of Season 50

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Gold Rate Forecast

- How to Build a Waterfall in Enshrouded

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- The 10 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Enterprise

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- Mishal Husain talks her new chapter, pressing Nigel Farage on Russia and the recent BBC troubles

2026-02-10 12:35