Author: Denis Avetisyan

Advances in muon beam technology are opening unprecedented avenues for exploring fundamental physics, from probing the structure of matter to searching for new particles and interactions.

![The layout of the MUon Science Establishment at J-PARC, as detailed in reference [Kawamura:2018apy], provides the infrastructure necessary for advanced research utilizing muons-elementary particles crucial for investigating fundamental physics and material science.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15818v1/muse.png)

This review details the progress and future potential of muon beams and muonium as tools for precision measurements in areas including muon spin rotation/relaxation/resonance, atomic spectroscopy, and searches for lepton flavor violation.

Despite the established successes of the Standard Model, fundamental questions regarding lepton flavor and the nature of dark matter remain open. This review, ‘Muon beams towards muonium physics: progress and prospects’, details recent advances in the generation and utilization of intense, polarized muon beams for precision measurements. Exploiting these beams-and techniques like muon spin rotation/relaxation/resonance (μSR)-allows for stringent tests of fundamental symmetries and increasingly sensitive searches for physics beyond the Standard Model, as well as novel insights into material science. Will continued improvements in muon beam technology unlock new pathways to understanding the universe’s deepest mysteries and reveal the subtle deviations from established theory?

The Fleeting Glimpse: Muons as Probes of Reality

Muons, fleeting elementary particles born from the decay of pions, function as remarkably versatile probes into the structure of matter and the forces governing the universe. Unlike more stable particles, muons possess a substantial mass yet undergo relatively rapid decay, allowing them to interact with and reveal subtle details about their surroundings before disappearing. This unique characteristic enables scientists to utilize muons in diverse applications, from mapping the internal structure of atoms and molecules – revealing magnetic moments and charge distributions – to investigating the properties of materials and even peering into the depths of large structures like volcanoes or pyramids. Because muons interact weakly with matter, they can penetrate significant distances, providing a non-destructive means of investigation unavailable with other methods, and offering insights into phenomena ranging from superconductivity to the search for extra dimensions.

Muons possess a compelling suite of characteristics that render them exceptionally useful across multiple scientific disciplines. As fundamental particles with intrinsic spin and a measurable magnetic moment, they interact with magnetic fields in predictable ways, allowing for precision measurements of these fields and the underlying structure of matter. Critically, the muon’s relatively short decay lifetime – approximately 2.2 microseconds – presents both a challenge and an advantage; it necessitates rapid detection techniques, but also enables sensitivity to transient phenomena and provides a natural “clock” for certain experiments. In particle physics, these properties are leveraged to probe the Standard Model and search for new physics, while in materials science, muon spin rotation, relaxation, and resonance techniques reveal information about magnetic ordering, superconductivity, and the atomic-scale structure of materials with unparalleled detail.

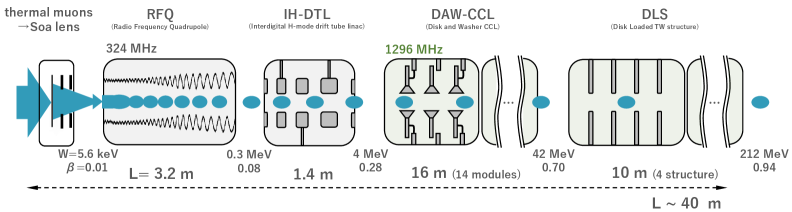

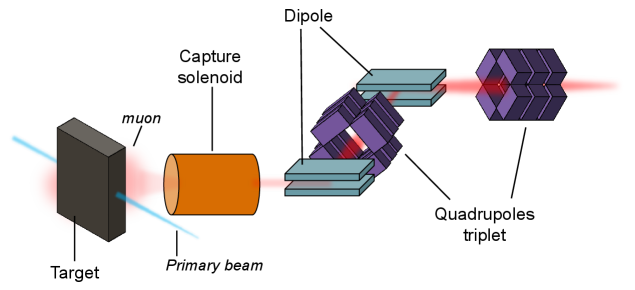

The creation and control of muons represent a significant technological undertaking, necessitating the development of highly specialized facilities like particle accelerators and beamlines. Unlike more stable particles, muons are short-lived, demanding extremely high production rates to generate a usable flux for experiments. Achieving this requires accelerating charged particles – typically protons – to relativistic speeds and directing them onto a target, initiating a cascade of secondary particles including pions, which subsequently decay into muons. Furthermore, manipulating these muons – focusing, cooling, and storing them – presents considerable challenges due to their relatively large mass and short lifetime. Innovations in accelerator magnet technology, radiofrequency cavities, and sophisticated cooling techniques, such as muon ionization cooling, are continually pursued to enhance beam intensity and precision, thereby extending the reach of fundamental physics investigations and materials science applications.

Global Laboratories: The Engines of Muon Production

Fermilab, the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI), and the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (J-PARC) represent the forefront of muon source development globally. These laboratories utilize high-intensity proton accelerators – specifically, Fermilab’s Proton Improvement Plan II (PIP-II), PSI’s ring cyclotron, and J-PARC’s 39 GeV proton synchrotron – to generate secondary particle beams including muons. Muon production relies on directing these high-energy proton beams onto target materials, initiating interactions that create a cascade of particles, from which muons are then selected and focused. Each facility has demonstrated the capability to produce muon beams with intensities exceeding 10^7 muons per second, and are currently undergoing upgrades aimed at increasing this output significantly to meet the demands of next-generation experiments.

Muon production techniques vary across leading facilities; Fermilab, PSI, and J-PARC each utilize distinct methodologies for generating and manipulating muon beams. PSI, for example, operates the Low Energy Muon (LEM) beamline, which employs a surface muon source and dedicated transport systems optimized for low-momentum muons \approx 1-{60} MeV/c. Fermilab and J-PARC, conversely, prioritize higher-energy beams produced through pion decay, necessitating different focusing and cooling techniques. These specialized beamlines, tailored to specific energy ranges and experimental needs, are critical for maximizing muon flux and controlling beam properties such as polarization and momentum spread.

Current facilities like Fermilab, PSI, and J-PARC are actively pursuing increases in muon beam intensity to meet the demands of next-generation experiments. These efforts center around optimizing proton accelerator performance and improving muon production target designs and beam collection systems. The targeted intensity of 10^{10} muons per second is considered crucial for enhancing statistical precision and enabling the exploration of rare processes in muon-based physics, including searches for charged lepton flavor violation and precise measurements of the muon anomalous magnetic moment. Achieving this goal necessitates advancements in beam cooling techniques, high-power targetry, and efficient beam transport to minimize muon losses and maximize delivered beam flux.

Precision Frontiers: Unveiling New Physics with Muons

The Mu2e and MACE experiments are designed to search for muon-electron conversion, a process that violates lepton flavor conservation as predicted by the Standard Model. These experiments utilize intense beams of muons, typically produced through pion decay at a proton accelerator, directed onto a target nucleus. The signature of lepton flavor violation is the observation of an electron, with energy and momentum characteristic of the muon, appearing without a corresponding muon signal. Mu2e, located at Fermilab, aims to improve the current search limit by a factor of 104, while MACE, planned for TRIUMF, will utilize a unique all-at-once momentum selection to enhance sensitivity. Both experiments require significant advancements in detector technology and beam instrumentation to achieve the required sensitivity and suppress background events.

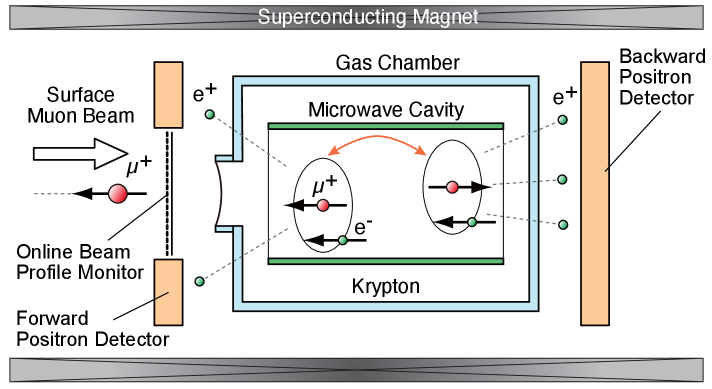

Muonium, an atom consisting of an electron orbiting a muon, serves as a sensitive testing ground for Quantum Electrodynamics (QED) due to the muon’s mass – approximately 200 times that of the electron. This larger mass enhances relativistic effects, making discrepancies from QED predictions more pronounced and thus easier to detect. Recent spectroscopic measurements of the hyperfine structure of muonium have achieved a precision of 160 parts per billion (ppb). This level of precision allows for stringent tests of QED predictions, specifically validating the theory’s predictions regarding the interaction between leptons and electromagnetic fields. The experimental setup typically involves creating muonium through the decay of positive pions or positrons in a low-density gas, followed by laser spectroscopy to measure the 2S-2P transition frequency – a key parameter for testing QED.

Muon Spin Rotation (MuSR) is a sensitive local probe of magnetic fields within materials. This technique involves implanting polarized muons into a sample, where they act as sensitive magnetic dipoles. The evolution of the muon spin polarization is then measured as a function of time using positron detection, revealing information about the local magnetic fields experienced by the muons. Variations in the muon spin precession frequency and relaxation rates directly correlate with the strength and distribution of magnetic fields, enabling the identification of magnetic phases, the detection of static and dynamic magnetism, and the investigation of exotic quantum phenomena like superconductivity and magnetism in complex materials. The technique is applicable to a wide range of materials, including superconductors, magnetic alloys, and topological materials.

The Art of Control: Innovations in Muon Beam Technology

Muon beams, crucial for probing fundamental particle physics and potentially enabling revolutionary technologies, suffer from rapid divergence due to the muons’ relatively short lifespan and inherent momentum spread. Muon cooling techniques directly address this limitation by reducing the beam’s transverse and longitudinal momentum spread, effectively squeezing the particle density. This isn’t achieved through conventional refrigeration; instead, specialized methods like ionization cooling – where muons lose energy through interactions with a material, then are re-accelerated – and stochastic cooling, which uses feedback from individual particle measurements, are employed. A denser, more focused beam dramatically increases the luminosity – a measure of the collision rate – in experiments, thereby enhancing the probability of observing rare events and enabling more precise measurements of particle properties. Ultimately, advancements in muon cooling are pivotal for maximizing the scientific return from current and future muon facilities, pushing the boundaries of what is observable in the subatomic world.

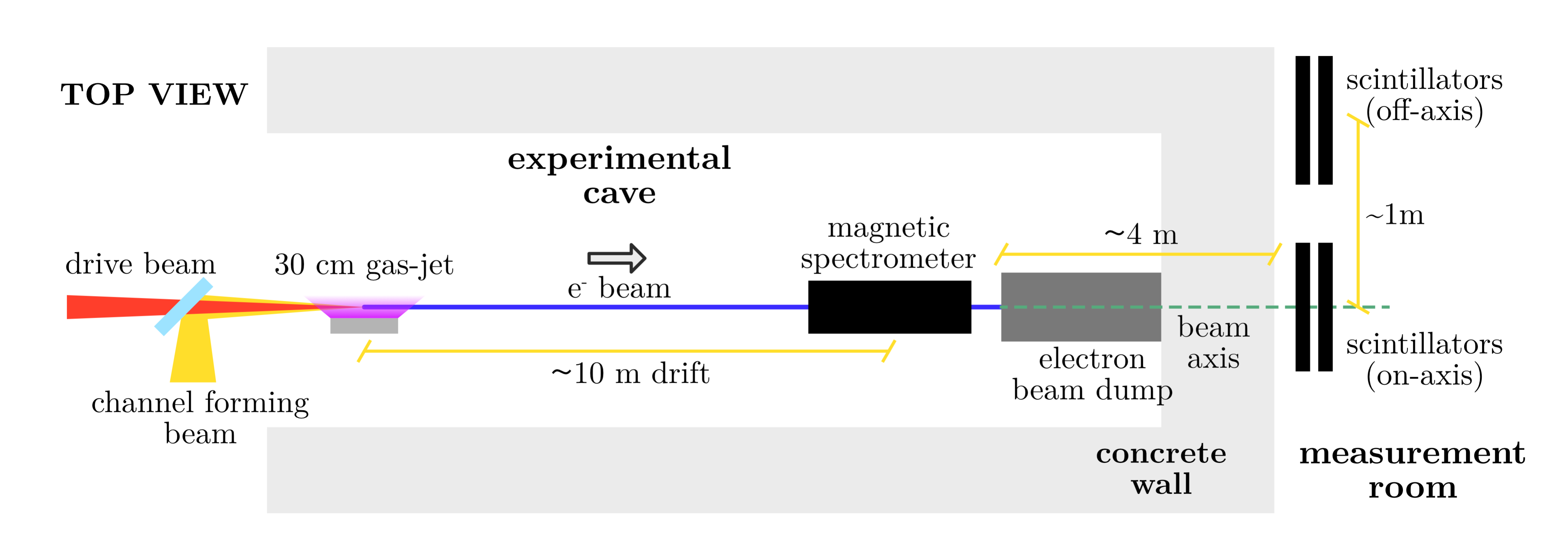

Laser Wakefield Acceleration (LWFA) represents a significant departure from traditional radio-frequency (RF) acceleration, offering the potential to dramatically shrink the size and cost of future muon accelerators. Conventional accelerators rely on bulky copper structures to generate accelerating fields; LWFA, however, utilizes intense laser pulses propagating through a plasma to create plasma waves – essentially, “wakes” – with exceptionally high electric fields, orders of magnitude greater than those achievable with RF technology. These intense fields can then accelerate charged particles, like muons, over very short distances – potentially reducing accelerator size from kilometers to mere meters. While challenges remain in maintaining beam quality and achieving stable acceleration, recent advances in laser technology and plasma control demonstrate the feasibility of LWFA for muon acceleration, opening exciting prospects for compact facilities dedicated to fundamental particle physics and applications like muon colliders and precision measurements.

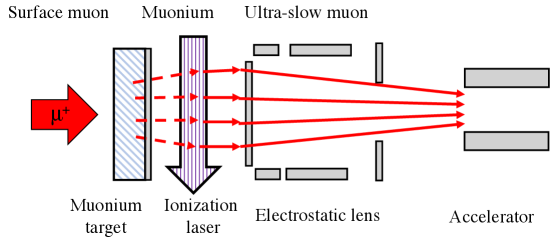

Recent advancements in material science have yielded a significant breakthrough in muonium beam production, leveraging optimized silica aerogel structures. Researchers have successfully achieved a muonium vacuum yield of 8.2%, a substantial improvement over previous methods. This achievement centers on carefully engineered aerogel, a highly porous solid, which provides an ideal environment for forming muonium-an atom consisting of a muon orbiting an electron. The enhanced yield is critical because muonium serves as a valuable probe for investigating fundamental physics, including tests of quantum electrodynamics and searches for new forces. Efficient muonium beam production unlocks possibilities for precision measurements and opens doors to explore exotic atomic and molecular systems, ultimately advancing the frontiers of particle and materials science.

Looking Ahead: Muons and the Future of Discovery

Muons are instrumental in probing the mysteries of antimatter, particularly through innovative experiments focused on antihydrogen – the simplest anti-atom. Unlike electrons used in many atomic studies, muons possess a significantly larger mass, allowing for more precise measurements and enhanced sensitivity when investigating the properties of antihydrogen. These studies aim to test fundamental symmetries of nature, such as Charge-Parity-Time (CPT) symmetry, which predicts that matter and antimatter should behave identically except for having opposite charges. By meticulously comparing the behavior of hydrogen and antihydrogen – including spectroscopic measurements and gravitational interactions – researchers hope to uncover any subtle differences that could explain the observed matter-antimatter asymmetry in the universe. The creation of antihydrogen requires energetic collisions and careful manipulation of particles within electromagnetic traps, and muons play a key role in optimizing these processes and increasing the precision of these delicate experiments.

Advancements in particle physics and materials science are increasingly reliant on the availability of intense and precisely controlled muon beams. These beams, created through complex accelerator technologies, serve as powerful probes for investigating fundamental symmetries of nature and the properties of matter. Current research focuses on developing novel muon sources – including those leveraging plasma wakefield acceleration – to significantly increase beam intensity and quality. Such improvements are critical for pushing the boundaries of experiments like muon g-2, which seeks to reveal discrepancies between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements, potentially hinting at physics beyond the Standard Model. Simultaneously, muon beams are proving invaluable in materials science, enabling techniques like muon spin rotation, relaxation, and resonance – \mu SR – to study the magnetic properties of materials with unprecedented sensitivity, aiding in the development of new superconductors and advanced magnetic materials.

Recent investigations into the gravitational behavior of antihydrogen – the antimatter counterpart of hydrogen – have established a remarkably stringent upper limit on the possibility that antimatter does not interact with gravity as predicted by standard models. Through precise measurements utilizing trapped antihydrogen atoms, researchers have effectively excluded, with a high degree of confidence, the scenario where antimatter experiences no gravitational attraction. Specifically, the probability of observing absolutely no gravitational interaction has been limited to a value of 2.9 \times 10^{-4}. This finding doesn’t confirm gravitational attraction, but it dramatically constrains theoretical models proposing deviations from Einstein’s equivalence principle for antimatter, pushing the boundaries of precision testing and opening avenues for exploring potential asymmetries between matter and antimatter in the universe.

The pursuit of precision measurements, as detailed in the exploration of muon beams and muonium physics, echoes a fundamental principle of elegant design: clarity through simplicity. Just as a well-crafted interface minimizes extraneous elements to reveal underlying structure, so too does this research strive to isolate and refine measurements to unveil the subtle nuances of fundamental particles. Bertrand Russell observed, “The point of the game is to find a form of expression which is at once precise and beautiful.” This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the endeavor described within – a quest not merely for data, but for a harmonious understanding of the universe, achieved through meticulous experimentation and the refinement of technique. The advancements in muon beam production, and techniques like μSR, demonstrate this dedication to achieving a state where observation and understanding converge with exceptional clarity.

The Harmony Yet Unheard

The pursuit of precision with muon beams, as this review demonstrates, is not merely a technical exercise. It’s a search for the subtle overtones in the universe’s composition-a striving for an elegance that suggests a deeper, more coherent structure. Current limitations in beam intensity and polarization, however, represent dissonances in this potential harmony. The interface doesn’t quite sing. Progress demands not simply brighter beams, but beams shaped with an understanding of the delicate resonance they seek to probe.

Muonium, as a leptonic hydrogen, remains a uniquely sensitive instrument. Yet, fully realizing its potential requires addressing the systematic uncertainties that currently obscure the faintest signals. A greater emphasis on novel detection schemes, and a willingness to explore unconventional accelerator designs, could unlock a new register of precision. The temptation to build ever-larger facilities must be tempered by a commitment to thoughtful experimentation – to listening for the quiet notes, not simply amplifying the noise.

Ultimately, the quest for lepton flavor violation and tests of the Standard Model with muons is a testament to the power of indirect measurement. Every detail matters, even if unnoticed. The true challenge lies not just in improving existing techniques, but in envisioning entirely new ways to interrogate the fabric of reality-to compose a symphony of data where every instrument plays in perfect tune.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15818.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- Donkey Kong Country Returns HD version 1.1.0 update now available, adds Dixie Kong and Switch 2 enhancements

- How To Watch A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms Online And Stream The Game Of Thrones Spinoff From Anywhere

- Hytale: Upgrade All Workbenches to Max Level, Materials Guide

- Darkwood Trunk Location in Hytale

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- PS5’s Biggest Game Has Not Released Yet, PlayStation Boss Teases

- Arc Raiders Guide – All Workbenches And How To Upgrade Them

- When to Expect One Piece Chapter 1172 Spoilers & Manga Leaks

- Sega Insider Drops Tease of Next Sonic Game

2026-01-23 11:55