Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are leveraging Bayesian inference and scattering transforms to build more robust imaging systems, especially when data is scarce.

This review details a novel framework for solving inverse problems by inferring the statistics of a field’s scattering transform using Bayesian methods, offering improved performance in low-data and non-Gaussian scenarios.

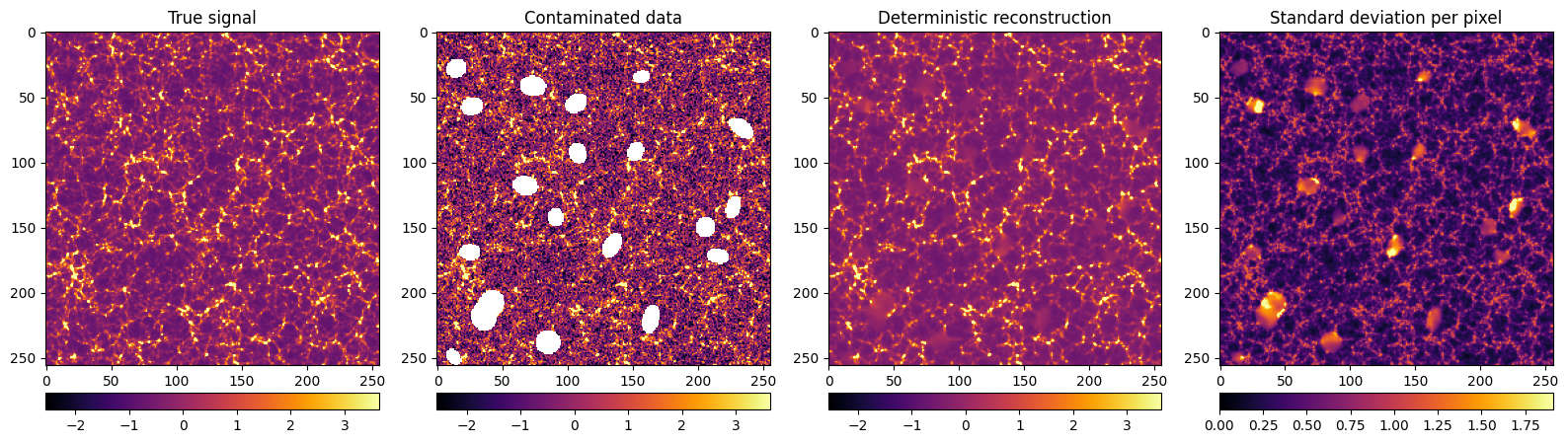

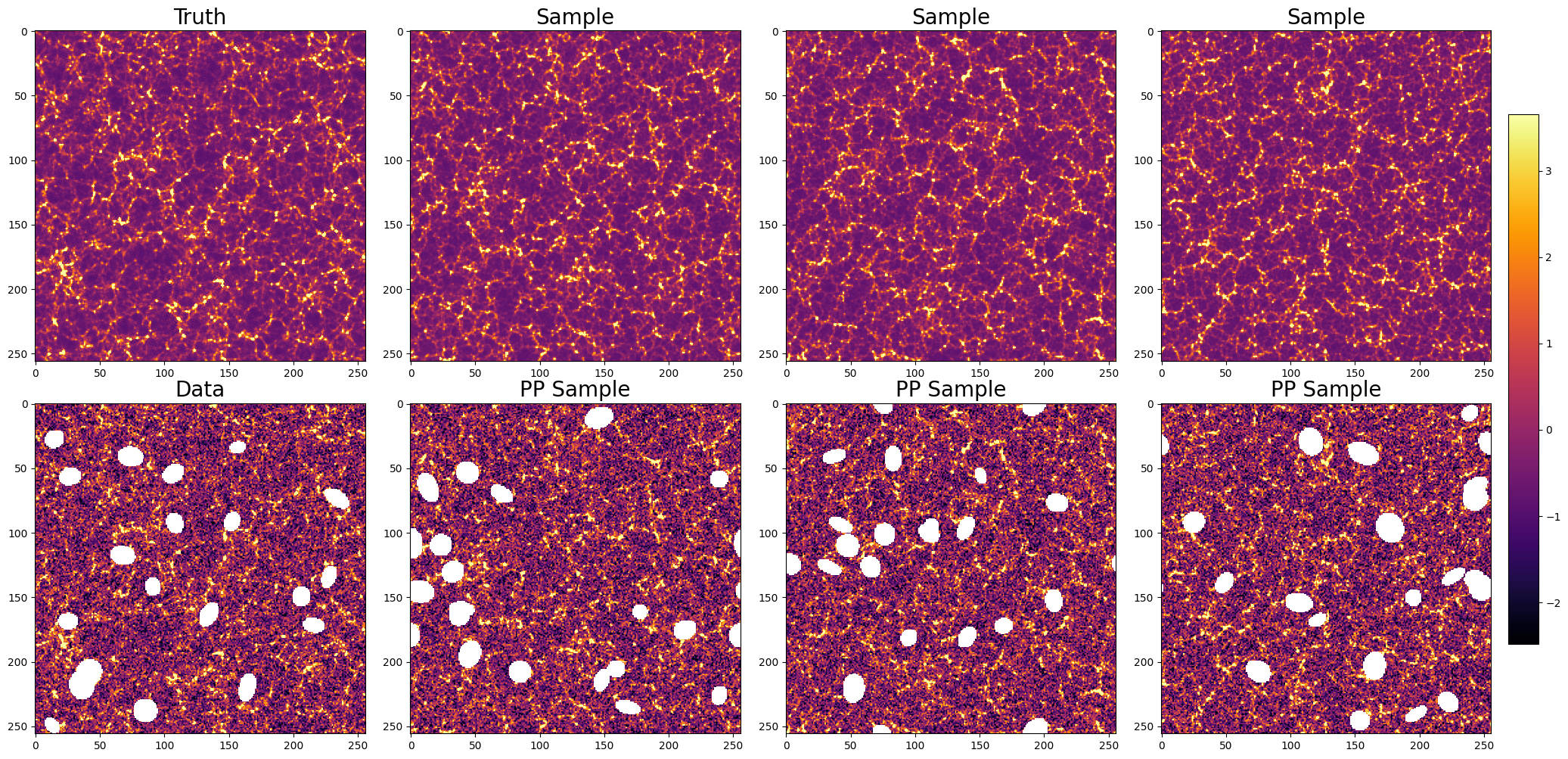

Reconstructing signals from limited or noisy data remains a fundamental challenge in imaging, particularly when dealing with complex, non-Gaussian fields. This paper, ‘Bayesian imaging inverse problem with scattering transform’, introduces a novel Bayesian framework that addresses these difficulties by shifting the inference objective from direct signal reconstruction to estimating the statistics of its Scattering Transform representation. This approach enables robust inference in a compact model space, facilitating accurate statistical reconstruction and deterministic signal recovery even from single, contaminated observations without relying on pre-defined priors. Could this method unlock new avenues for analyzing complex astrophysical and cosmological signals where prior modeling is scarce or unreliable?

The Illusion of Knowing: Reconstructing Hidden Realities

The reconstruction of hidden structures from incomplete or indirect observations, known as imaging inverse problems, presents a fundamental challenge across diverse scientific disciplines. From medical imaging – where doctors seek to visualize internal organs from X-rays or MRI data – to geophysics, which aims to map subsurface features using seismic waves, and even astronomy, which reconstructs distant galaxies from faint light, the core task remains the same: inferring an unknown cause from limited effects. These problems are ‘inverse’ because they represent the reverse of the forward process – simulating observations from a known structure – and are inherently more difficult due to the loss of information during the observation process. Successfully tackling these inverse problems often requires sophisticated mathematical techniques and computational algorithms to navigate inherent ambiguities and noise, ultimately revealing the hidden structure with sufficient clarity and accuracy.

Many techniques used to reconstruct hidden structures from incomplete data-a common challenge in fields like medical imaging and geophysics-begin by assuming a ‘Linear Gaussian Likelihood’. This simplification posits that the relationship between the hidden structure and the observations is linear, and that any noise corrupting the observations follows a Gaussian (normal) distribution. While mathematically convenient, this assumption frequently breaks down when dealing with the complexities of real-world phenomena. Non-linear relationships are pervasive, and noise often deviates significantly from a Gaussian profile-perhaps exhibiting heavy tails or being systematically biased. Consequently, relying on this simplified model can lead to blurred images, inaccurate reconstructions, and ultimately, flawed interpretations of the underlying data, necessitating more sophisticated approaches to account for these inherent complexities.

The challenge of inferring hidden structures from limited observations is significantly amplified when dealing with the ‘low-data regime’. In this scenario, the number of available measurements is comparable to, or even fewer than, the number of unknown parameters defining the hidden structure. This scarcity of data leads to a dramatic increase in uncertainty and ambiguity; multiple models can often explain the observations equally well, hindering the ability to confidently reconstruct the underlying truth. Consequently, standard inference techniques, which rely on sufficient data to pinpoint a unique solution, become unreliable, often producing solutions that are far from the actual hidden structure. Robust statistical methods and regularization techniques are therefore crucial in this regime, aiming to stabilize the inference process and prevent overfitting to the limited data – effectively navigating a landscape of high uncertainty to arrive at the most plausible reconstruction.

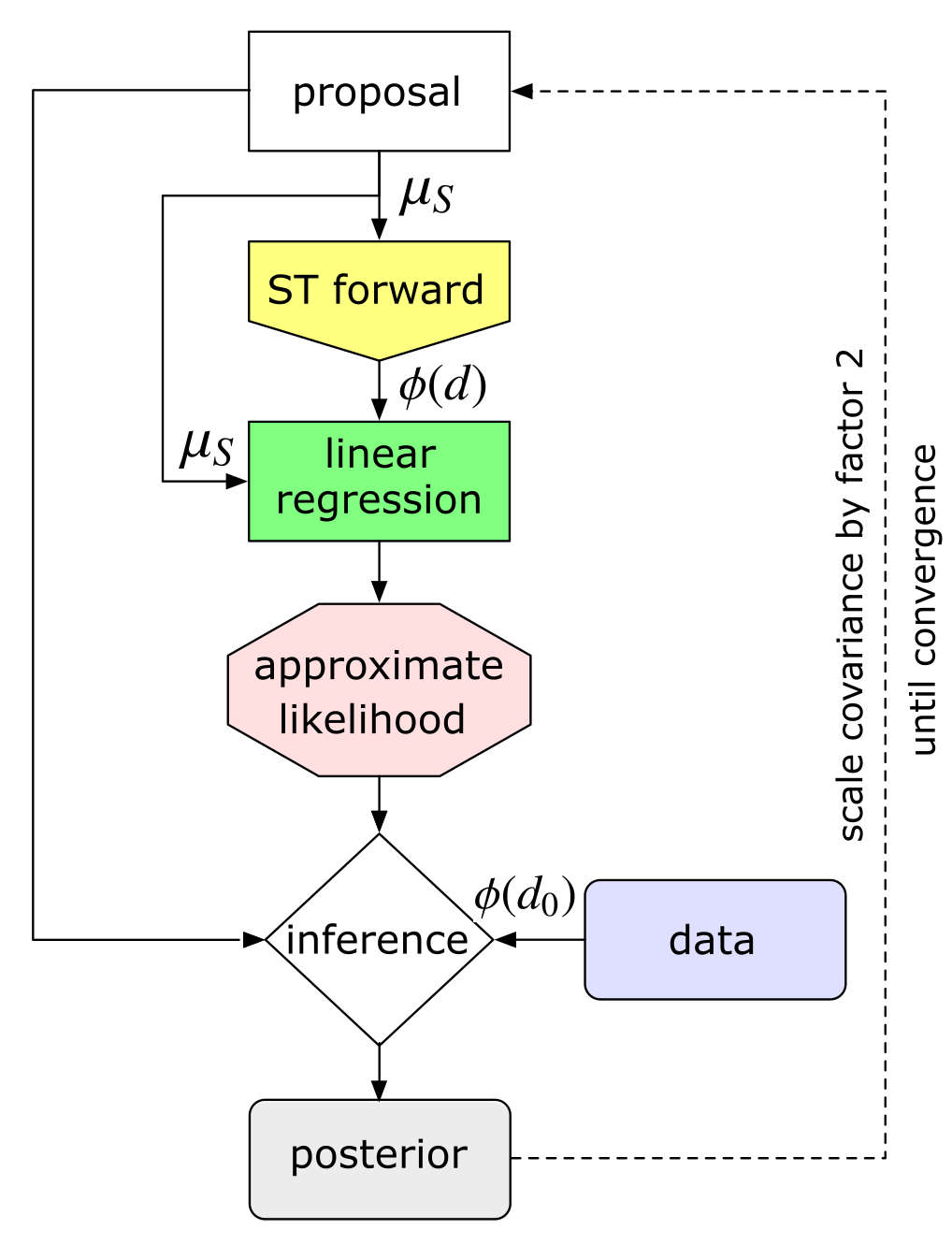

Iterative Refinement: Chasing Clarity in the Murk

Iterative algorithms estimate the posterior distribution of a signal through repeated application of a forward model and comparison to observed data. This approach is particularly useful when direct calculation of the posterior is intractable, which is common in complex signal processing scenarios. The algorithm begins with an initial guess of the signal and iteratively refines this estimate by minimizing the difference between the predicted observation (based on the forward model) and the actual observation. Each iteration updates the signal estimate based on the residual error, converging towards the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate or, with appropriate techniques, approximating the full posterior distribution p(s|d), where s represents the underlying signal and d represents the observed data.

Ridge Regression and Sequential Likelihood Estimation (SLE) are employed to improve the performance of iterative algorithms used for signal estimation. Ridge Regression addresses ill-posed inverse problems by adding a regularization term – typically the squared L_2 norm of the signal – to the objective function, preventing overfitting and increasing solution stability. SLE, conversely, updates the signal estimate sequentially as new data becomes available, allowing for real-time processing and adaptation to changing signal characteristics. This sequential approach minimizes the impact of outlier measurements and provides a more robust estimate compared to batch processing methods. Both techniques contribute to increased accuracy by reducing variance and bias in the estimated posterior distribution.

The accuracy of iterative refinement algorithms is fundamentally dependent on the ‘Forward Operator’, which mathematically relates the unobserved, underlying signal to the measurable, observed data. This operator, often denoted as H, defines the physics or process by which the signal is transformed into the data. Effectively, d = H s + n, where d represents the observed data, s the underlying signal, and n noise. The Forward Operator can be a matrix, an integral transform, or a more complex function. Precisely defining and accurately representing this operator is crucial; errors in its formulation directly propagate into inaccuracies in the estimated signal. The choice of Forward Operator is dictated by the specific characteristics of the signal and the measurement process.

Beyond Gaussianity: Mapping the True Complexity

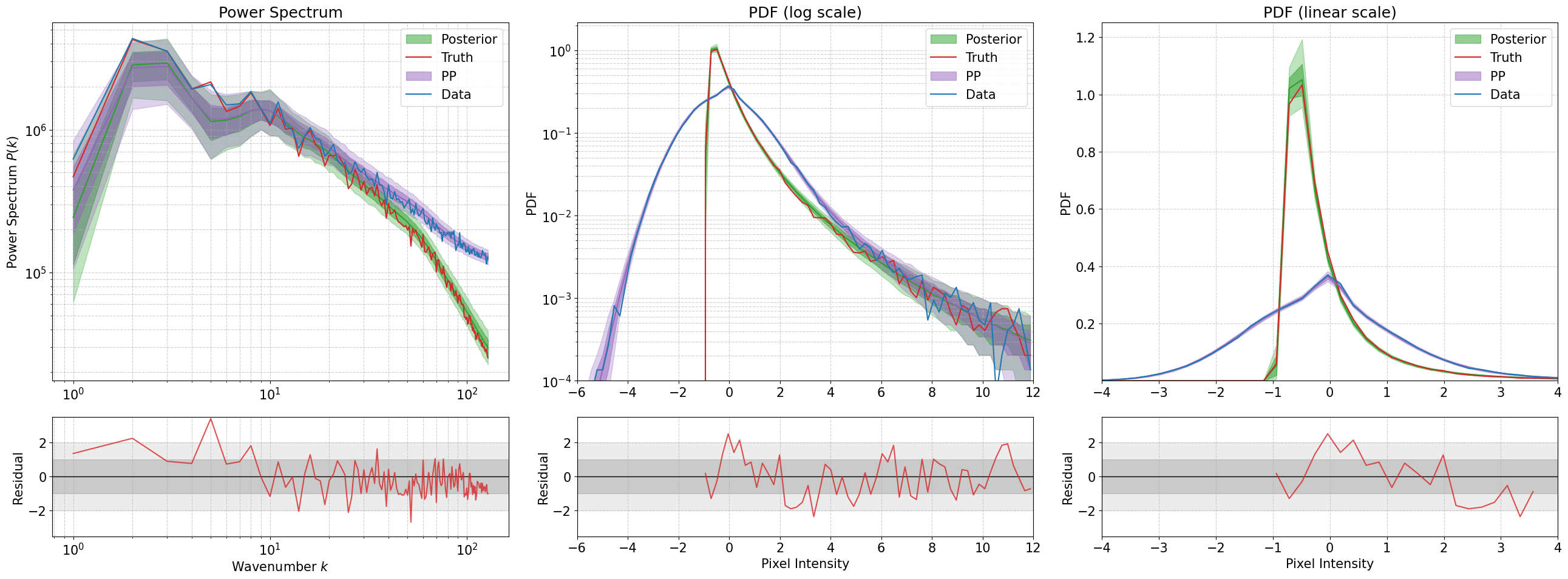

A significant number of signals encountered in practical applications, such as images, audio, and seismic data, deviate from the Gaussian distribution commonly assumed by many signal processing techniques. This non-Gaussianity arises from the inherent complexity of these signals and the non-linear interactions present within them. Traditional methods, predicated on Gaussian statistics, can therefore produce suboptimal or inaccurate results when applied to these signals. The failure of the Gaussian assumption impacts the performance of techniques relying on second-order statistics, necessitating the use of higher-order statistics or alternative representations capable of accurately characterizing the non-Gaussian field properties of the signal.

The Scattering Transform (ST) is a wavelet-based signal processing technique designed to efficiently characterize non-Gaussian signals by decomposing them into a multi-scale representation. Unlike Fourier analysis, which is sensitive to translation, the ST is translation-invariant, providing robustness to shifts in the input signal. This is achieved by repeatedly convolving the signal with wavelet filters and then downsampling, effectively capturing information at different scales and orientations. The key advantage of the ST lies in its ability to model interactions between these scales, which is crucial for analyzing complex signals where energy is distributed non-uniformly across frequencies. By analyzing the statistical properties of the transformed signal at each scale, the ST provides a compact and informative representation of the original signal’s structure, particularly its non-Gaussian characteristics.

The application of statistics derived from the Scattering Transform (ST) enables substantial dimensionality reduction in signal analysis. Specifically, operating on ST coefficients transforms a problem initially defined by a 256×256 data space – representing, for example, a 256×256 image – into a more manageable 243-dimensional space. This reduction is achieved through the inherent properties of the ST, which efficiently captures signal features across multiple scales and orientations, allowing for a compact statistical representation. Consequently, analysis and reconstruction processes become computationally less expensive and require significantly less memory, while still retaining critical information about the original signal.

Validation and the Limits of Our Perception

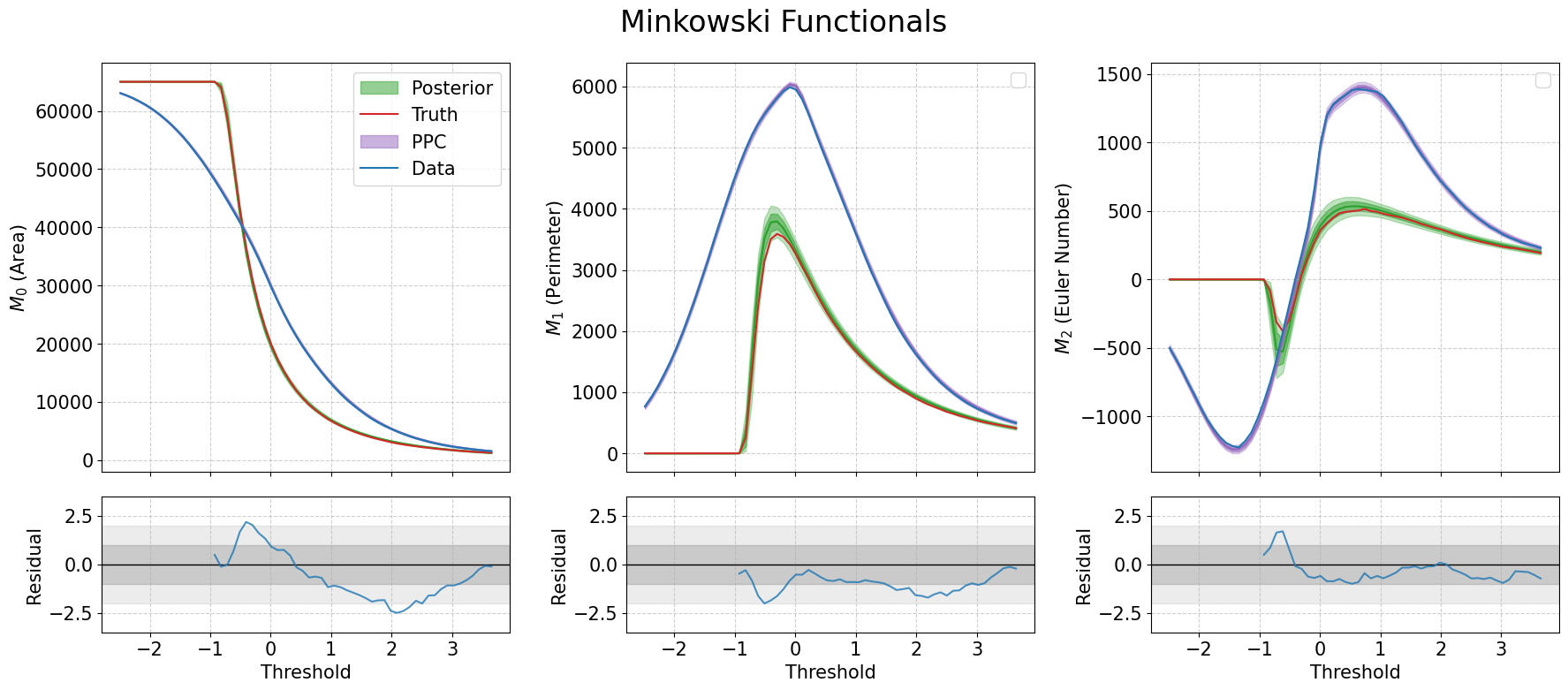

The efficacy of this imaging framework hinges on its ability to perform reliably with real-world data, which is often plagued by noise and imperfections. To rigorously assess performance beyond idealized conditions, researchers leveraged the ‘Quijote’ simulation – a sophisticated tool capable of generating highly realistic astronomical datasets. This simulation doesn’t simply create random noise; it models the complex physical processes that govern the formation of cosmic structures and the propagation of light, resulting in data that closely mimics observations from actual telescopes. By testing the algorithm on these simulated datasets, scientists could confidently validate its performance across a range of challenging scenarios, ensuring it’s not merely succeeding on artificially clean data but is genuinely robust and prepared for the complexities of astronomical imaging. This approach provides a crucial benchmark, establishing a high degree of confidence in the framework’s ability to deliver accurate and reliable results when applied to genuine observational data.

The presented framework addresses the notoriously difficult class of imaging inverse problems – those where reconstructing an image requires deciphering information lost or distorted during its acquisition – through a novel integration of iterative algorithms and scattering transforms. This combination proves remarkably robust, even when faced with substantial noise, limited data, or complex scattering environments that typically plague image reconstruction. Scattering transforms efficiently decompose the imaging data, capturing essential structural information while suppressing irrelevant details; this pre-processed data then feeds into an iterative algorithm that refines the image estimate step-by-step. The synergy between these two approaches allows the algorithm to navigate the ambiguity inherent in inverse problems, consistently converging toward accurate reconstructions where traditional methods often fail, thus opening possibilities for enhanced imaging in fields ranging from medical diagnostics to remote sensing.

The developed algorithm exhibits a remarkably swift convergence, consistently reaching a stable solution within approximately 15 training epochs. While computational resources permitted extending the training to 40 epochs, this extended duration served a conservative purpose – ensuring the solution’s robustness and minimizing the potential for oscillations or divergence. This rapid convergence, coupled with the demonstrated stability, highlights the algorithm’s efficiency and practicality for real-world applications where processing time and reliability are paramount. The comparatively low number of epochs needed to achieve a stable result represents a significant advantage over many existing iterative methods, suggesting a streamlined and optimized approach to solving imaging inverse problems.

The presented work navigates the complexities inherent in inverse problems, particularly when dealing with limited data and non-Gaussian fields. It proposes a shift in perspective, focusing on inferring the scattering transform statistics rather than directly reconstructing the field itself. This approach echoes a sentiment articulated by Pierre Curie: “One never notices what has been done; one can only see what remains to be done.” The paper acknowledges the inherent limitations in reconstructing a complete field, instead concentrating on characterizing its statistical properties – a focus on what can be reliably determined, much like recognizing the boundaries of knowledge and proceeding from there. The utilization of scattering transforms offers a powerful tool for statistical analysis, allowing for robust reconstruction even in challenging low-data regimes, while acknowledging the irreducible uncertainties that remain beyond the event horizon of complete information.

What Lies Beyond the Horizon?

This work, by shifting focus from direct reconstruction to inference of scattering transform statistics, offers a subtle reminder: the map is not the territory. It’s a graceful sidestep in the face of ill-posed problems, particularly when data is scarce and assumptions about Gaussianity falter. But even elegant statistical reconstructions remain tethered to the priors imposed, to the generative models chosen-and those, inevitably, reflect the limits of current understanding. The cosmos generously shows its secrets to those willing to accept that not everything is explainable.

Future investigations will undoubtedly refine the Bayesian framework, explore alternative scattering transforms, and wrestle with the complexities of non-Gaussian fields. However, a more fundamental challenge looms: the very act of seeking a ‘reconstruction’ might be a category error. Perhaps the true task isn’t to recover an objective reality, but to build models that usefully represent information, even if those representations are inherently subjective and incomplete.

Black holes are nature’s commentary on human hubris. This research, while technically proficient, implicitly acknowledges that the information lost beyond the event horizon isn’t necessarily ‘recoverable’ in any meaningful sense-only approximated, modeled, and constrained by the tools at hand. The pursuit of knowledge, then, becomes a continuous negotiation with uncertainty, a humbling recognition that complete understanding is an illusion.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05816.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- 7 Home Alone Moments That Still Make No Sense (And #2 Is a Plot Hole)

- Stephen Colbert Jokes This Could Be Next Job After Late Show Canceled

- DCU Nightwing Contender Addresses Casting Rumors & Reveals His Other Dream DC Role [Exclusive]

- Is XRP ETF the New Stock Market Rockstar? Find Out Why Everyone’s Obsessed!

- 10 Best Hercule Poirot Novels, Ranked

- 10 X-Men Batman Could Beat (Ranked By How Hard It’d Be)

- Ashes of Creation Rogue Guide for Beginners

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Death in Paradise’s Don Gilet responds to character criticism: ‘I don’t have to defend Mervin’

2026-02-08 03:05