Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research details a method for testing the predictions of Einstein’s theory of gravity using X-ray reflections from material swirling around black holes.

A relativistic ray-tracing model based on non-circular metrics enables testing deviations from General Relativity with X-ray reflection spectroscopy of accreting black holes.

While General Relativity has consistently passed observational tests, alternative theories and solutions predict deviations from the spacetime symmetry expected around black holes. This motivates research such as ‘Testing non-circular black hole spacetime with X-ray reflection’, which presents a novel framework for constraining these deviations using X-ray reflection spectroscopy and a relativistic ray-tracing code adapted for non-circular metrics. Analysis of \textit{NuSTAR} data from the black hole binary EXO 1846–031 reveals no statistically significant evidence for spacetime deformation, remaining consistent with the Kerr hypothesis-though the methodology demonstrates the feasibility of future, more sensitive tests. Will upcoming observations with enhanced spectral resolution finally reveal deviations from the predictions of Einstein’s theory in the strong gravity regime?

The Enduring Legacy of General Relativity

For over a century, Albert Einstein’s General Relativity has remained a cornerstone of modern physics, fundamentally reshaping understanding of gravity not as a force, but as a curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. This revolutionary theory accurately predicts the behavior of objects in gravitational fields, from the subtle precession of Mercury’s orbit to the bending of light around massive objects – predictions repeatedly confirmed by observation. Perhaps most strikingly, General Relativity foretold the existence of gravitational waves – ripples in spacetime caused by accelerating massive objects – and black holes, regions where gravity is so intense that nothing, not even light, can escape. The initial detection of gravitational waves in 2015 by the LIGO collaboration, originating from the merger of two black holes, served as a spectacular validation, confirming a key prediction made a century prior and opening a new window into the cosmos. These successes demonstrate the theory’s enduring power and continue to inspire ongoing research into the universe’s most extreme environments.

Recent advancements in observational astronomy have delivered compelling evidence bolstering the predictions of General Relativity. The LIGO-VIRGO-KAGRA collaboration has directly detected gravitational waves – ripples in spacetime – originating from cataclysmic events like merging black holes and neutron stars, precisely matching the waveforms predicted by Einstein’s theory. Simultaneously, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration achieved the unprecedented feat of imaging the supermassive black hole at the center of the M87 galaxy, revealing a shadow consistent with the strong gravitational field described by General Relativity. These observations, independently obtained through different methodologies, not only confirm the theory’s validity in extreme gravitational regimes but also open new avenues for probing the fundamental nature of spacetime and black holes themselves, marking a golden age for relativistic astrophysics.

While General Relativity remains remarkably accurate in most gravitational scenarios, its predictive power falters when confronted with the universe’s most extreme conditions. Attempts to reconcile the theory with observations of black hole interiors and the very first moments after the Big Bang reveal mathematical inconsistencies, suggesting the theory breaks down at singularities – points of infinite density. Furthermore, the observed accelerating expansion of the universe, driven by a mysterious force dubbed ‘dark energy’, cannot be naturally explained within the framework of General Relativity; its inclusion requires the introduction of an unexplained cosmological constant or the postulation of entirely new forms of energy and matter. These discrepancies don’t invalidate the theory, but instead highlight its limitations and motivate the ongoing search for a more complete theory of gravity, potentially involving quantum effects or modifications to the geometry of spacetime itself.

Beyond Einstein: Exploring Modified Spacetime

Modified Gravity theories represent a class of physical models that depart from the established framework of General Relativity to resolve specific theoretical problems and observational discrepancies. These theories propose adjustments to the gravitational field equations, often by introducing additional terms or fields, to address issues such as the existence of dark energy, the nature of dark matter, or the presence of spacetime singularities predicted by General Relativity in scenarios like black holes and the Big Bang. The motivation stems from the inability of General Relativity, in its current form, to fully reconcile with cosmological observations or provide a complete description of extreme gravitational environments. Modifications can involve altering the Einstein-Hilbert action, introducing higher-order curvature terms, or postulating the existence of additional scalar or vector fields mediating gravitational interactions, all with the aim of achieving a more comprehensive and accurate description of gravity.

Non-Circular Metrics represent a departure from the Kerr Metric, which is the standard solution in General Relativity describing the spacetime geometry around rotating, uncharged black holes. While the Kerr Metric predicts event horizons and ergospheres characterized by axisymmetric, circular symmetry, Non-Circular Metrics allow for deviations from this symmetry. These deviations manifest as distortions in the shape of these features, potentially resulting in event horizons and ergospheres that are not perfectly circular. The exploration of these alternative metrics is motivated by theoretical considerations and attempts to reconcile General Relativity with observational data, particularly in strong gravitational fields where deviations from the Kerr solution might be detectable. These metrics are often generated by modifying the Einstein field equations or introducing additional fields, resulting in a different set of solutions for spacetime curvature around rotating black holes.

The Einstein-Æther theory postulates the existence of a dynamical, unit timelike vector field – the “æther” – which breaks Lorentz invariance and introduces a preferred frame of reference. Solutions to the field equations of this theory, when applied to rotating black holes, produce Non-Circular Metrics that differ from the standard Kerr metric g_{\mu\nu}. These Non-Circular Metrics exhibit deviations in the spacetime geometry around rotating black holes, specifically manifesting as distortions in the ergosphere and alterations to the shape of the event horizon. The resulting spacetime is no longer axisymmetric, and the theory predicts observable differences in the gravitational waveforms emitted during black hole mergers compared to those predicted by General Relativity. These deviations stem from the æther’s influence on the propagation of gravitational waves and the structure of spacetime itself.

Probing Strong Gravity: The Language of X-rays

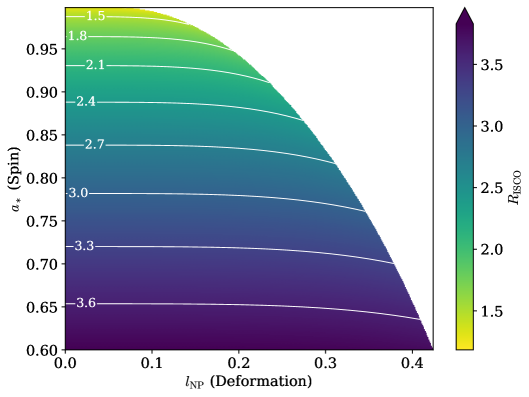

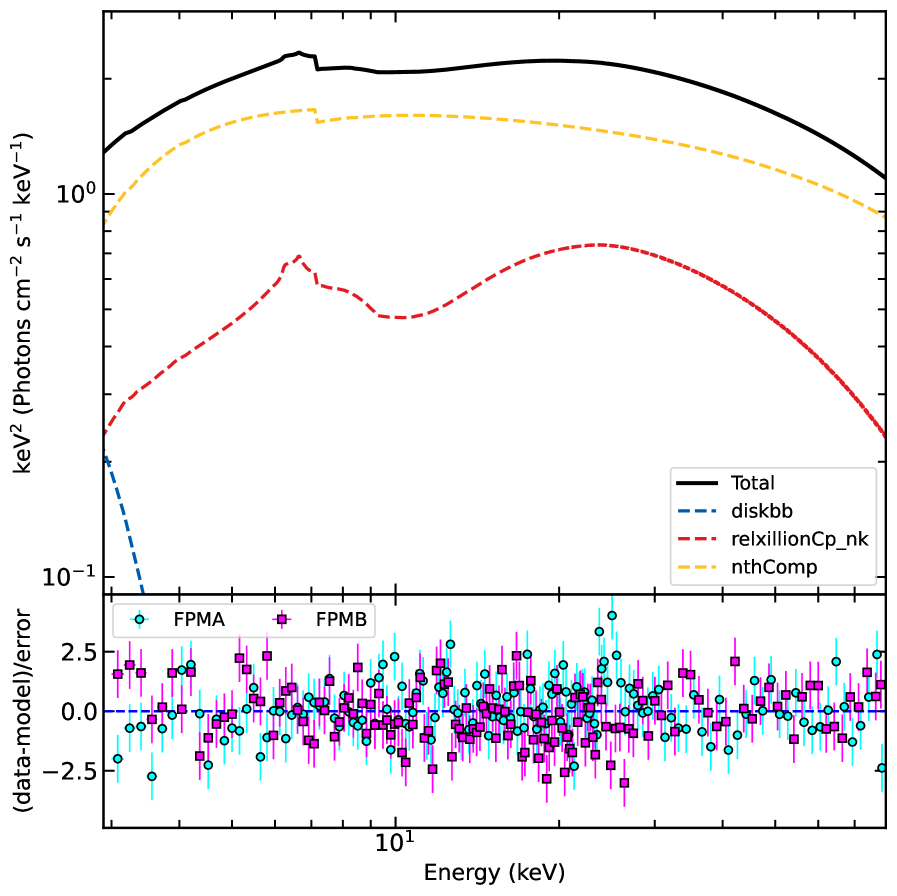

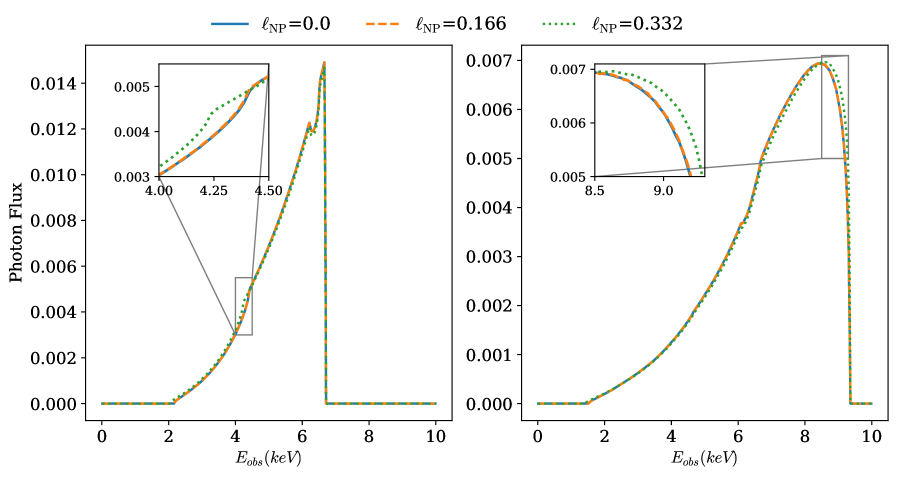

X-ray Reflection Spectroscopy (XRS) is an astrophysical technique used to study the environments surrounding black holes. It operates by analyzing the X-rays emitted from a hot accretion disk and subsequently reflected off the inner edge of the disk or any surrounding corona. These reflected X-rays are not simple copies of the emitted radiation; they are significantly altered due to several effects including Doppler shifting, gravitational redshift, and most importantly, the extreme bending of spacetime near the black hole. The distortions in the reflected spectrum contain information about the geometry of the accretion disk, the black hole’s spin, and the strength of the gravitational field, allowing researchers to probe the strong-gravity regime and test predictions of general relativity. The intensity and shape of specific spectral features, such as broadened iron lines, are directly linked to these relativistic effects.

Relativistic ray tracing is a fundamental component of X-ray reflection spectroscopy, used to simulate the paths of photons as they travel through the intense gravitational field surrounding black holes. This modeling is necessary because strong gravity significantly bends and distorts photon trajectories, altering the observed X-ray spectrum. Accurate ray tracing requires a precise description of the spacetime geometry, typically defined by the Kerr metric which describes a rotating black hole. The code utilizes ingoing Kerr coordinates to trace photons emitted from the accretion disk, accounting for effects like gravitational redshift, time dilation, and Doppler boosting. The complexity arises from the need to integrate photon paths numerically, considering the effects of general relativity on both the photon’s position and its observed energy at the detector.

Accurate interpretation of X-ray spectra from accreting black holes requires complex spectral modeling. Specifically, the models `relxill_nk`-which simulates relativistic reflection-`diskbb`-representing the thermal emission from the accretion disk-`nthComp`-modeling the Comptonized emission-and `tbabs`-accounting for absorption by intervening material-are essential components. This research addressed the need for robust analysis by developing and implementing a ray-tracing code operating in ingoing Kerr coordinates. This code allows for the precise calculation of photon trajectories in the strong gravitational field near a rotating black hole, enabling detailed fitting of the observed X-ray spectra and subsequent constraints on black hole spin and accretion disk geometry.

Locality and the Search for Deviations

The Locality Principle posits a fundamental connection between potential deviations from Einstein’s General Relativity and the strength of local gravitational fields. This concept suggests that any modification to the established theory will manifest most prominently in regions where curvature is extreme, such as near black holes or neutron stars. Rather than introducing alterations that affect spacetime globally, this principle favors scenarios where deviations are intrinsically linked to the immediate environment’s gravitational intensity – effectively stating that changes to gravity should ‘localize’ around strong curvature. Consequently, researchers focusing on modified gravity theories often concentrate on high-curvature regimes, seeking to identify subtle differences in spacetime geometry that would confirm or refute these alternative models. This approach allows for a more constrained search for new physics, as it narrows the scope of investigation to areas where deviations are predicted to be most significant and potentially observable.

The construction of non-circular metrics, geometries that deviate from the standard circular symmetry expected around black holes, relies heavily on the mathematical utility of ingoing Kerr coordinates. These coordinates, initially developed to describe rotating black holes within General Relativity, provide a natural framework for exploring modified gravity theories. By adapting the Kerr metric within this coordinate system, researchers can systematically introduce deviations that represent alternative spacetime structures. This approach allows for the modeling of black hole geometries where the event horizon isn’t perfectly circular, potentially arising from exotic matter or modifications to Einstein’s field equations. The resulting non-circular metrics are not merely theoretical constructs; they provide a concrete mathematical basis for analyzing observational data and testing the limits of General Relativity, offering a pathway to discern whether observed astrophysical phenomena require physics beyond the standard model.

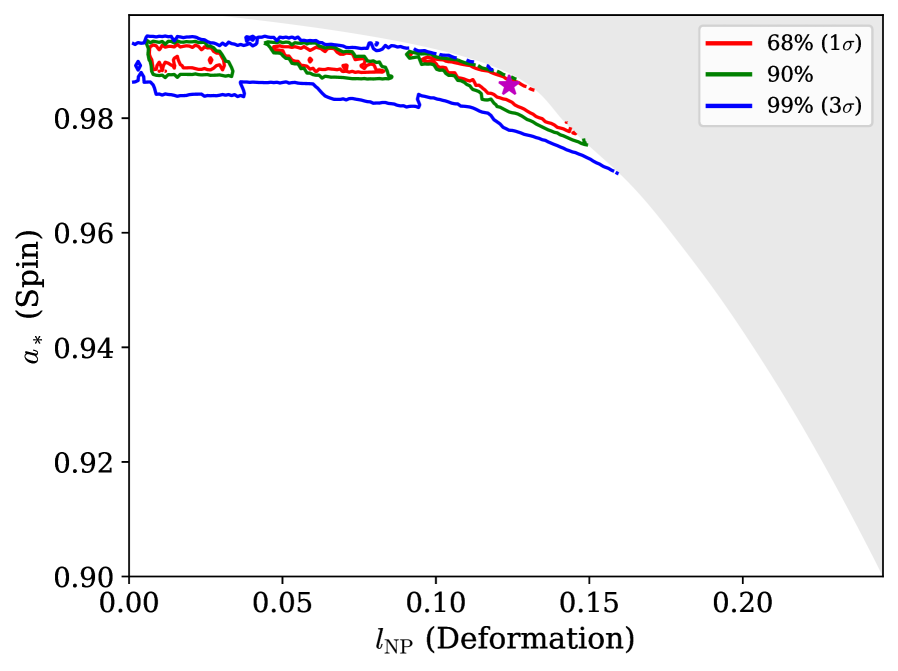

Specific solutions to modified gravity theories manifest as non-circular geometries around black holes, with the Disformal Kerr Solution serving as a concrete example. Recent analysis of the X-ray binary EXO 1846-031 provides observational constraints on these geometries, revealing a maximum deformation parameter \ell_{NP} of 0.124; however, current data allows for considerable flexibility in this value. This system’s derived spin parameter a* of 0.982 indicates a near-extremal black hole, a configuration particularly sensitive to deviations from General Relativity. Importantly, observations suggest that the effects of these deformations are most pronounced when viewing the system at high inclinations-up to 80°-providing a key avenue for future observational tests of modified gravity in the strong-field regime.

The presented methodology rigorously examines the spacetime geometry surrounding black holes, seeking to validate or refute predictions of General Relativity. This pursuit echoes a sentiment articulated by Isaac Newton: “I have not been able to discover the composition of any body.” Similarly, this research doesn’t presume to know the definitive nature of black hole spacetime, but instead proposes a precise framework – built upon non-circular metrics and relativistic ray tracing – to test existing theories and potentially reveal deviations. The careful construction of the model, akin to a mathematical proof, emphasizes the need for demonstrable accuracy over mere observational agreement, aligning with a commitment to verifiable, logical foundations in understanding the universe.

Beyond the Horizon

The presented methodology, while rigorous in its application of relativistic ray tracing to non-circular geometries, ultimately highlights the inherent limitations of observational confirmation. To posit a deviation from General Relativity requires not merely a statistical preference for a modified metric, but a demonstrably necessary departure – a symmetry broken by observation, not merely hinted at by error bars. Current instrumentation, even at its zenith, can only probe so deeply into the near-field regime, leaving the far-field behavior – the true signature of modified gravity – frustratingly obscured.

Future progress necessitates a shift in focus. The pursuit of ever-more-complex metrics, while mathematically elegant, risks overfitting to noise. A more fruitful avenue lies in identifying specific, theoretically-motivated deviations – predictions carved from first principles, rather than sculpted by parameter estimation. Such predictions, even if initially narrow in scope, offer a sharper test – a potential falsification that elevates the inquiry beyond mere model comparison.

Ultimately, the enduring challenge remains: to distinguish between the exquisitely precise predictions of a well-established theory and the subtle, perhaps illusory, signatures of something beyond. The pursuit is not simply about finding alternatives to General Relativity, but about revealing the fundamental symmetries – or lack thereof – that govern the universe at its most extreme limits.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16562.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Controller Settings for ARC Raiders

- 10 Most Memorable Batman Covers

- Netflix’s Stranger Things Replacement Reveals First Trailer (It’s Scarier Than Anything in the Upside Down)

- Star Wars: Galactic Racer May Be 2026’s Best Substitute for WipEout on PS5

- ‘Crime 101’ Ending, Explained

- Legacy of Kain: Ascendance announced for PS5, Xbox Series, Switch 2, Switch, and PC

- The Best Members of the Flash Family

- Ashes of Creation Mage Guide for Beginners

- 24 Years Later, Star Trek Director & Writer Officially Confirm Data Didn’t Die in Nemesis

- Best X-Men Movies (September 2025)

2026-02-19 15:20