Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach proposes leveraging the precision of orbiting quantum clocks to detect the elusive influence of ultralight dark matter on the fabric of spacetime.

This review explores the potential of space-based experiments to detect ultralight scalar dark matter by searching for violations of the Weak Equivalence Principle and distortions induced by dilaton couplings.

Despite the compelling evidence for dark matter, its fundamental nature remains elusive, prompting exploration beyond traditional WIMP models. This paper, ‘Searching for Ultralight Scalar Dark Matter with Clocks in Low Earth Orbit’, investigates the potential of utilizing highly sensitive quantum clocks to detect ultralight dark matter through its subtle couplings to standard model particles and the resulting distortions of the surrounding dark matter field. We demonstrate that space-based clocks, particularly those deployed in Low Earth Orbit, are uniquely positioned to probe dark matter masses m_{\rm DM}\gtrsim 10^{-{10}} \text{\, eV} and leverage temporal modulations induced by Earth’s gravity as a powerful detection mechanism. Could these novel approaches unlock a new window into the composition of the dark universe and reveal the existence of fifth-force interactions?

The Universe’s Hidden Mass: A Persistent Mystery

The composition of the universe presents a profound mystery: roughly 85% of all matter is dark matter, a substance that does not interact with light or, crucially, with any particles described by the Standard Model of particle physics. Decades of increasingly sensitive experiments designed to detect dark matter through its weak interactions with ordinary matter have yielded no conclusive evidence. This absence of detection doesn’t invalidate the overwhelming astronomical evidence for dark matter – observed through its gravitational effects on galaxies and the cosmic microwave background – but it does highlight a fundamental gap in our understanding of the universe. The continued failure to identify dark matter particles within the Standard Model framework suggests that its nature is far more complex, potentially involving interactions beyond those currently known to science and necessitating the exploration of entirely new theoretical paradigms.

The persistent inability to directly detect dark matter particles, despite decades of searching, highlights a fundamental disconnect between current theoretical frameworks and observational evidence. Existing models, largely built upon the successes of the Standard Model of particle physics, predict interaction strengths and particle masses that should have yielded detection signals by now. The absence of these signals suggests that dark matter’s behavior deviates significantly from expectations, demanding a shift in theoretical approach. Consequently, researchers are increasingly focused on exploring novel interaction paradigms – beyond simple Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) – that encompass a broader range of possibilities, including axions, sterile neutrinos, and even primordial black holes. This necessitates a re-evaluation of fundamental assumptions about dark matter’s nature and its interactions with both ordinary matter and itself, opening up exciting avenues for discovery in the realm of particle physics and cosmology.

The ongoing quest to understand dark matter necessitates a rigorous program of precision tests designed to probe the limits of established physics. Existing theoretical frameworks, collectively known as the Standard Model, fail to account for the observed abundance and properties of dark matter, signaling the need to venture beyond its confines. This pursuit involves not only searching for potential dark matter particles directly, but also scrutinizing fundamental constants and physical laws with unprecedented accuracy. Subtle deviations from Standard Model predictions – in areas like particle interactions, gravitational phenomena, or the behavior of neutrinos – could reveal the fingerprints of new physics and illuminate the nature of this mysterious substance. Consequently, experiments are being developed to push the boundaries of measurement, exploring hypothetical particles and forces that may mediate interactions between dark matter and ordinary matter, ultimately reshaping the current understanding of the universe.

The search for dark matter has increasingly focused on ultralight candidates, particles so light they behave as waves rather than discrete entities. This wave-like nature offers a potential solution to the ‘missing satellite’ and ‘too-big-to-fail’ problems in galactic structure formation, but also introduces significant detection challenges. A crucial parameter defining this behavior is mass; specifically, masses greater than approximately 3 \times 10^{-{11}} \text{ eV} are favored because they ensure the dark matter’s de Broglie wavelength – the distance characterizing its wave nature – is substantially smaller than the Earth’s radius. This shorter wavelength is vital; it allows these particles to cluster gravitationally and form the structures observed in the universe, while avoiding the quantum mechanical effects that would dilute their density and render them undetectable with current methods. Investigating this mass range, therefore, represents a promising avenue in the ongoing quest to unravel the mystery of dark matter and refine models of cosmic structure.

Precision Timekeeping: A New Window onto the Dark Universe

The prevailing model of dark matter suggests it may interact with standard model particles, potentially causing measurable variations in fundamental constants. Specifically, the fine-structure constant, α, which governs the strength of electromagnetic interactions, is susceptible to shifts induced by the presence of dark matter fields. These variations would manifest as changes in atomic energy levels and the frequencies of transitions between them. Ultralight dark matter, behaving as a wave, could induce time-dependent oscillations in α, detectable through high-precision spectroscopic measurements. The magnitude of these expected variations is extremely small, requiring clock technologies with unprecedented stability and accuracy to differentiate a signal from background noise.

Current precision clock technologies – including Quantum Clocks, Nuclear Clocks, and Atomic Clocks – achieve fractional frequency stabilities exceeding 10^{-{18}}. This level of precision represents a significant advancement over previous timekeeping methods and is crucial for detecting subtle variations in fundamental constants. These clocks operate by referencing highly stable quantum transitions within atoms or nuclei, allowing for extremely accurate time measurement. The improved stability enables the detection of shifts in resonant frequencies that would be indicative of interactions with dark matter, offering a sensitivity several orders of magnitude beyond previous experimental constraints. Specifically, these clocks can resolve frequency shifts as small as a few Hertz, opening a new window for dark matter searches.

Ultralight dark matter, theorized to have a mass on the order of 10^{-{22}} to 10^{-{18}} eV, exhibits wave-like behavior due to its extremely low mass. This wave-like nature leads to periodic variations in the local dark matter density, creating a fluctuating gravitational field. Precision clocks, such as those based on atomic, nuclear, or quantum phenomena, are uniquely suited to detect these subtle gravitational shifts because their operational frequencies are directly affected by changes in the local gravitational potential. The interaction between the oscillating dark matter field and the clock’s frequency standard manifests as minute frequency drifts that, while exceptionally small, are within the detection limits of current and near-future precision timekeeping technologies. The amplitude of these drifts is dependent on the dark matter particle’s mass and coupling strength to standard model particles.

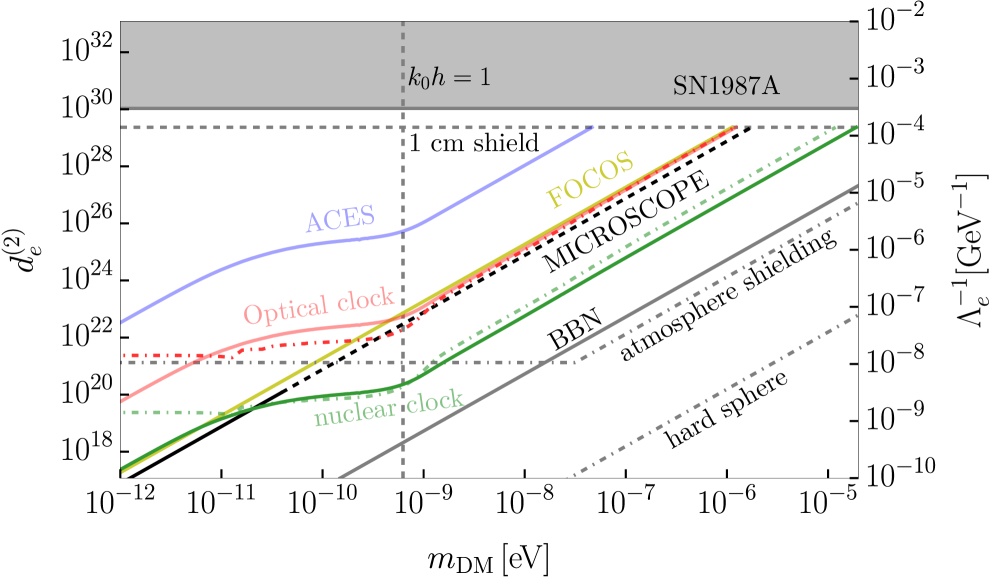

Current experimental efforts leverage highly precise timekeeping to search for interactions between ordinary matter and dark matter candidates. These experiments, utilizing Quantum, Nuclear, and Atomic Clocks, operate by continuously monitoring for variations in fundamental constants which would manifest as shifts in resonant frequencies. By maintaining rigorously controlled environments and employing advanced data analysis techniques, these setups aim to achieve sensitivities exceeding those of previous experiments like MICROSCOPE, which placed limits on the variation of the gravitational constant. Specifically, researchers are targeting interactions predicted to arise from the wave-like properties of ultralight dark matter, potentially detecting minute oscillatory signals in the measured time intervals.

Observing the Invisible: Optimizing Clock Measurements in Space

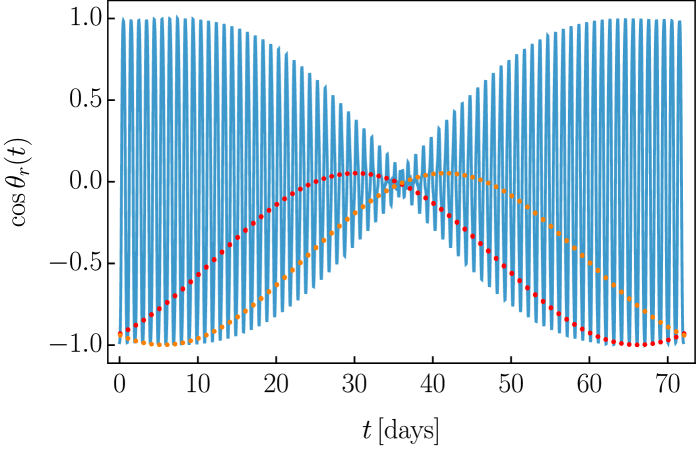

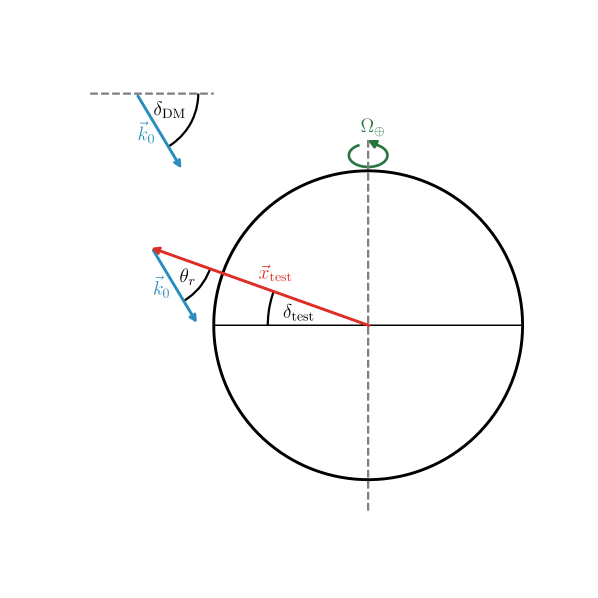

Deploying atomic clocks in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) offers advantages for dark matter detection due to reduced environmental noise and extended observation periods. Specifically, altitudes of h \lesssim 1000 km are prioritized because theoretical models predict the dipole term of the dark matter field profile is most significant at these distances from Earth. This dipole component induces a measurable frequency shift in the clocks, and minimizing external disturbances-such as gravitational gradients and electromagnetic interference-in LEO enhances the sensitivity to this subtle signal. Longer observation times in orbit, compared to ground-based experiments, accumulate sufficient data to statistically differentiate the dark matter-induced clock rate variations from background noise.

Differential clock measurements, achieved through comparisons between space-based clocks and ground-based clocks, as well as between multiple clocks in space, significantly improve the sensitivity of dark matter detection experiments. These comparisons isolate the subtle frequency shifts induced by potential dark matter interactions by cancelling out common-mode noise sources such as gravitational redshift and relativistic effects. Space-to-ground comparisons establish a baseline, while space-to-space comparisons – utilizing multiple clocks at varying altitudes or orbital configurations – allow for the precise mapping of spatial gradients in the dark matter field and further reduction of systematic errors. The resulting differential signals are considerably larger and more readily detectable than absolute frequency measurements alone, enhancing the experiment’s ability to constrain dark matter properties.

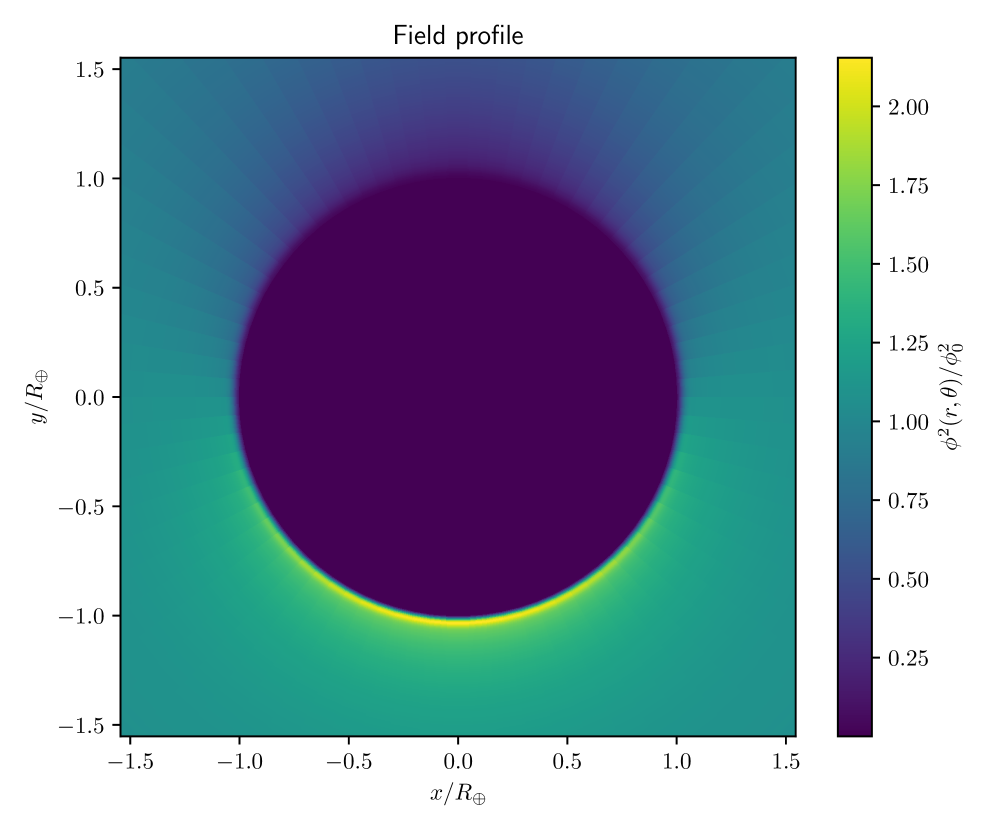

Legendre polynomials are employed to model the spatial distribution of the dark matter field and its subsequent influence on clock rates due to gravitational time dilation. The dark matter density is not assumed to be uniform; instead, it’s represented by a series expansion using these orthogonal polynomials. This allows for the decomposition of the gravitational potential into a sum of multipole terms, where each term is weighted by a Legendre polynomial and a corresponding coefficient representing the amplitude of that spatial frequency. By accurately characterizing the coefficients, the contribution of the dark matter field to the observed clock rate differences can be precisely calculated and distinguished from other gravitational effects and relativistic phenomena. The use of P_l(cos(\theta)) where l represents the degree of the Legendre polynomial and θ is the angle of observation, enables the modeling of anisotropic dark matter distributions and their impact on clock synchronization.

The MICROSCOPE mission, launched in 2016, was primarily designed to test the equivalence principle with unprecedented accuracy; however, its highly sensitive differential accelerometer also provides constraints on potential interactions between dark matter and standard model particles. While not specifically intended as a dark matter detection experiment, MICROSCOPE’s measurement of the Eötvös parameter, η, places limits on certain dark matter models that predict forces acting on test masses. The experiment achieved a fractional accuracy of 10^{-{14}} on the Eötvös parameter, demonstrating the feasibility of using high-precision space-based accelerometry to search for subtle forces indicative of dark matter interactions and paving the way for future dedicated dark matter searches utilizing similar technologies.

Theoretical Underpinnings and Interaction Models

A compelling theoretical avenue for detecting dark matter hinges on the premise of quadratic coupling, which posits an interaction between dark matter particles and the particles comprising the Standard Model. This framework doesn’t predict a direct, strong force, but rather a weaker interaction proportional to the square of the masses involved – a m^2 dependence. Consequently, heavier Standard Model particles, such as the W and Z bosons, would exhibit a proportionally stronger coupling to dark matter than lighter particles like electrons. This mass dependence is crucial, as it suggests that experiments focusing on interactions with heavier particles may provide the most sensitive probes of this coupling. Furthermore, the quadratic nature of the interaction implies that dark matter scattering rates are generally small, necessitating highly sensitive detectors and strategies to distinguish these subtle signals from background noise – a challenge driving innovation in direct detection experiments worldwide.

Beyond the foundational concept of quadratic coupling, current theoretical investigations explore dilaton-like couplings as a means of refining the description of dark matter interactions. These couplings propose that the strength of the interaction between dark matter and Standard Model particles isn’t fixed, but rather dynamically scales with the energy of the interaction-a characteristic mirroring behavior observed in quantum chromodynamics. This nuanced approach acknowledges that dark matter may not couple uniformly to all particles, potentially explaining the absence of definitive detection despite ongoing experimental efforts. By allowing interaction strengths to vary, dilaton-like couplings offer a more flexible framework for modeling dark matter, accommodating a wider range of possible scenarios and potentially resolving discrepancies between theoretical predictions and observational constraints. Such models are critical for interpreting data from direct detection experiments, where subtle variations in interaction strengths could dramatically affect signal rates and spectral features.

The behavior of ultralight dark matter, theorized to possess wave-like properties due to its extremely low mass, is effectively modeled through the application of the Klein-Gordon equation. This relativistic wave equation, traditionally used in quantum mechanics to describe spin-0 particles, allows researchers to explore the potential for dark matter to exhibit phenomena like diffraction and interference. Unlike conventional particle dark matter, ultralight dark matter doesn’t clump as readily, instead forming interference patterns and creating unique density profiles within galaxies. Solving the Klein-Gordon equation under various gravitational potentials enables predictions about the distribution of this wave-like dark matter, which can then be compared with astronomical observations to constrain its mass and interaction properties. This approach is particularly useful in simulating the formation of galactic structures and predicting the resulting signals detectable by current and future dark matter experiments, offering a powerful tool for unraveling the mysteries surrounding this elusive substance.

Accurate interpretation of dark matter detection experiments hinges on a comprehensive understanding of matter effects, which can mimic or obscure genuine signals. These effects arise as dark matter particles interact with the nuclei of atoms within detector materials, altering their observed energy and direction. The magnitude of these alterations is particularly sensitive when the dark matter mass Δm_{DM} significantly exceeds the atmospheric Δm_{atm} and terrestrial Δm_{⊕} mass splittings – specifically when k_0^2 ≪ Δm_{DM}, Δm_{atm} ≪ Δm_{DM}, Δm_{⊕}. Under these conditions, the influence of matter on the observed dark matter signal becomes pronounced, demanding precise modeling to differentiate it from background noise. Consequently, space-based detectors, largely free from the terrestrial matter effects that complicate ground-based experiments, offer a superior environment for disentangling true dark matter interactions and refining the search for these elusive particles.

The Future of the Hunt: Beyond Current Limits

The search for dark matter extends beyond direct detection experiments to include innovative approaches like fifth-force searches. These experiments don’t attempt to directly observe dark matter particles, but instead meticulously examine the gravitational force itself, looking for subtle deviations from predictions based on general relativity. The underlying principle is that if dark matter interacts with ordinary matter through a force beyond gravity – a fifth force – it would manifest as minute changes in the expected gravitational behavior between objects. These forces, though expected to be incredibly weak, could become measurable through highly sensitive experiments utilizing techniques like torsion balances and atom interferometry. By establishing stringent limits on the strength and range of such potential fifth forces, researchers can effectively constrain theoretical models of dark matter, ruling out scenarios where these interactions are significant and paving the way for more accurate and focused searches.

A multifaceted approach to dark matter detection is proving essential, and the synergy between precision clock measurements and other experimental probes is central to this progress. Atomic clocks, capable of discerning minute shifts in time caused by interactions with dark matter, aren’t operating in isolation; data from these instruments is being combined with results from direct detection experiments – which search for dark matter particles colliding with ordinary matter – and indirect detection methods, observing the byproducts of dark matter annihilation. This integration allows researchers to cross-validate findings, reduce systematic uncertainties, and explore a wider range of dark matter models than any single technique could achieve alone. By weaving together these diverse datasets, a more complete and robust picture of dark matter’s properties – its mass, interaction strength, and potential self-interactions – is gradually emerging, offering hope for finally unraveling this cosmic mystery.

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) offers a powerful, albeit indirect, method for evaluating dark matter models by examining the primordial abundances of light elements formed in the early universe. Shortly after the Big Bang, when temperatures and densities were extreme, protons and neutrons fused to create helium, deuterium, and lithium; the precise quantities of these elements are exquisitely sensitive to the overall density of baryonic matter – the ‘normal’ matter that interacts with light. Dark matter, by influencing the expansion rate of the early universe, alters the conditions under which BBN occurs, and thus affects the predicted elemental abundances. By meticulously comparing these predictions with observational data – obtained from quasar absorption spectra and pristine gas clouds – scientists can place stringent constraints on the properties of dark matter, effectively linking cosmological models of the early universe with present-day astronomical observations and providing an independent check on results obtained from direct detection experiments and collider searches.

The pursuit of dark matter detection is poised for a leap forward through innovations in precision timing technology. Current research focuses on developing atomic clocks capable of sustained operation with integration times reaching 108 seconds, particularly when deployed in co-located space-based systems. These highly sensitive instruments aim to detect minute variations in time caused by interactions with dark matter, effectively mapping the distribution and properties of this elusive substance. By extending observation durations and leveraging the stability of space-based platforms, scientists anticipate surpassing current detection limits and potentially unveiling the fundamental nature of dark matter – its mass, interaction strength, and role in the universe’s evolution. This approach complements existing search methods, offering a unique pathway to understanding a significant portion of the cosmos that remains hidden from direct observation.

The pursuit of ultralight dark matter, as detailed in this research, demands a relentless skepticism toward readily available ‘insights.’ It’s not enough to simply observe a deviation in clock readings; the challenge lies in systematically dismantling potential explanations, forcing a conclusion only through the exhaustion of alternatives. As Confucius observed, “Study the past if you would define the future.” This paper’s methodology, relying on precision measurements and rigorous testing of the Weak Equivalence Principle, mirrors that sentiment. The subtle distortions sought within the dark matter field aren’t revealed by grand pronouncements, but by patiently refining the boundaries of what can be confidently disproven. The more Legendre Polynomials computed, the more robust the rejection of false positives becomes – a truth often obscured by the allure of easily digestible ‘trends’.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The pursuit of ultralight dark matter via precision clock networks in space feels, at present, like constructing an exquisitely sensitive measuring device to detect a ghost. The theoretical landscape is, generously, populated with possibilities – dilaton couplings, Legendre polynomial-shaped potentials, and the lingering suspicion that the Weak Equivalence Principle might not be quite as inviolable as assumed. However, the signal, if it exists, is predicted to be vanishingly small, buried within a cacophony of terrestrial and orbital noise. To proceed, the field requires a brutal honesty regarding systematic errors. If everything fits the models, it’s not a triumph; it’s a failure of imagination regarding what was overlooked.

Future iterations will necessitate a clear-eyed assessment of which parameter spaces are truly accessible. The current focus, while logically motivated, risks being spread too thin. Perhaps a narrowing of scope – prioritizing specific mass ranges or coupling models – would yield a more definitive search. Furthermore, the challenge isn’t solely technological. A truly compelling detection demands independent corroboration. This means exploring complementary search strategies – terrestrial experiments, astrophysical observations – that can converge on the same dark matter candidates.

Ultimately, the value of this approach may not lie in a definitive “discovery,” but in the exquisitely refined understanding of fundamental physics that emerges from the attempt. The universe rarely yields its secrets willingly. The act of searching, of pushing the boundaries of precision measurement, is, in itself, a worthwhile endeavor. Even a null result, rigorously obtained, constrains the possibilities and guides the next generation of theorists and experimentalists.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16259.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- The 10 Best Episodes Of Star Trek: Enterprise

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

- Sunday Rose Kidman Urban Describes Mom Nicole Kidman In Rare Interview

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

2026-01-26 08:55